| Mesoderm | |

|---|---|

Tissues derived from mesoderm. | |

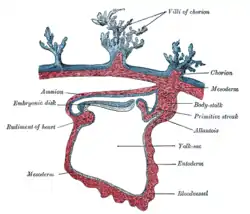

Section through a human embryo | |

| Details | |

| Days | 16 |

| Identifiers | |

| MeSH | D008648 |

| FMA | 69072 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The mesoderm is the middle layer of the three germ layers that develops during gastrulation in the very early development of the embryo of most animals. The outer layer is the ectoderm, and the inner layer is the endoderm.[1][2]

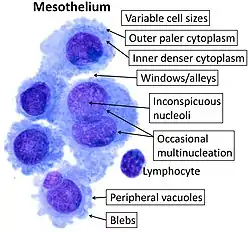

The mesoderm forms mesenchyme, mesothelium, non-epithelial blood cells and coelomocytes. Mesothelium lines coeloms. Mesoderm forms the muscles in a process known as myogenesis, septa (cross-wise partitions) and mesenteries (length-wise partitions); and forms part of the gonads (the rest being the gametes).[1] Myogenesis is specifically a function of mesenchyme.

The mesoderm differentiates from the rest of the embryo through intercellular signaling, after which the mesoderm is polarized by an organizing center.[3] The position of the organizing center is in turn determined by the regions in which beta-catenin is protected from degradation by GSK-3. Beta-catenin acts as a co-factor that alters the activity of the transcription factor tcf-3 from repressing to activating, which initiates the synthesis of gene products critical for mesoderm differentiation and gastrulation. Furthermore, mesoderm has the capability to induce the growth of other structures, such as the neural plate, the precursor to the nervous system.

Definition

The mesoderm is one of the three germinal layers that appears in the third week of embryonic development. It is formed through a process called gastrulation. There are four important components, which are the axial, paraxial, intermediate, and lateral plate mesoderms. The axial mesoderm gives rise to the notochord. The paraxial mesoderm forms the somitomeres, which give rise to mesenchyme of the head, and organize into somites in occipital and caudal segments, and give rise to sclerotomes (cartilage and bone), and dermatomes (subcutaneous tissue of the skin).[1][2] Signals for somite differentiation are derived from surroundings structures, including the notochord, neural tube, and epidermis. The intermediate mesoderm connects the paraxial mesoderm with the lateral plate. Eventually it differentiates into urogenital structures that consist of the kidneys, gonads, their associated ducts, and the adrenal cortex. The lateral plate mesoderm gives rise to the heart, blood vessels, and blood cells of the circulatory system, as well as to the mesodermal components of the limbs.[4]

Some of the mesoderm derivatives include the muscle (smooth, cardiac, and skeletal), the muscles of the tongue (occipital somites), the pharyngeal arches muscle (muscles of mastication, muscles of facial expressions), connective tissue, the dermis and subcutaneous layer of the skin, bone and cartilage, dura mater, the endothelium of blood vessels, red blood cells, white blood cells, microglia, the dentin of teeth, the kidneys, and the adrenal cortex.[5]

Development

During the third week, a process called gastrulation creates a mesodermal layer between the endoderm and the ectoderm. This process begins with the formation of a primitive streak on the surface of the epiblast.[6] The cells of the layers move between the epiblast and the hypoblast, and begin to spread laterally and cranially. The cells of the epiblast move toward the primitive streak and slip beneath it, in a process called "invagination". Some of the migrating cells displace the hypoblast and create the endoderm, and other cells migrate between the endoderm and the epiblast to create the mesoderm. The remaining cells form the ectoderm. After that, the epiblast and the hypoblast establish contact with the extraembryonic mesoderm until they cover the yolk sac and amnion. They move onto either side of the prechordal plate. The prechordal cells migrate to the midline to form the notochordal plate. The chordamesoderm is the central region of trunk mesoderm.[4] This forms the notochord, which induces the formation of the neural tube, and establishes the anterior-posterior body axis. The notochord extends beneath the neural tube from the head to the tail. The mesoderm moves to the midline until it covers the notochord. When the mesoderm cells proliferate, they form the paraxial mesoderm. In each side, the mesoderm remains thin, and is known as the lateral plate. The intermediate mesoderm lies between the paraxial mesoderm and the lateral plate. Between days 13 and 15, the proliferation of extraembryonic mesoderm, primitive streak, and embryonic mesoderm take place. The notochord process occurs between days 15 and 17. Eventually, the development of the notochord canal and the axial canal takes place between days 17 and 19, when the first three somites are formed.[7]

Paraxial mesoderm

During the third week, the paraxial mesoderm is organized into segments. If they appear in the cephalic region and grow with cephalocaudal direction, they are called somitomeres. If they appear in the cephalic region but establish contact with the neural plate, they are known as neuromeres, which later will form the mesenchyme in the head. The somitomeres organize into somites which grow in pairs. In the fourth week, the somites lose their organization and cover the notochord and spinal cord to form the backbone. In the fifth week, there are 4 occipital somites, 8 cervical, 12 thoracic, 5 lumbar, 5 sacral and 8 to 10 coccygeal that will form the axial skeleton. Somitic derivatives are determined by local signaling between adjacent embryonic tissues, in particular the neural tube, notochord, surface ectoderm and the somitic compartments themselves.[8] The correct specification of the deriving tissues, skeletal, cartilage, endothelia and connective tissue is achieved by a sequence of morphogenic changes of the paraxial mesoderm, leading to the three transitory somitic compartments: dermomyotome, myotome and sclerotome. These structures are specified from dorsal to ventral and from medial to lateral.[8] Each somite will form its own sclerotome that will differentiate into the tendon cartilage and bone component. Its myotome will form the muscle component and the dermatome that will form the dermis of the back. The myotome and dermatome have a nerve component.[1][2]

Molecular regulation of somite differentiation

Surrounding structures such as the notochord, neural tube, epidermis and lateral plate mesoderm send signals for somite differentiation[1][2] Notochord protein accumulates in presomitic mesoderm destined to form the next somite and then decreases as that somite is established. The notochord and the neural tube activate the protein SHH, which helps the somite to form its sclerotome. The cells of the sclerotome express the protein PAX1 that induces the cartilage and bone formation. The neural tube activates the protein WNT1 that expresses PAX 2 so the somite creates the myotome and dermatome. Finally, the neural tube also secretes neurotrophin 3, so that the somite creates the dermis. Boundaries for each somite are regulated by retinoic acid and a combination of FGF8 and WNT3a.[1][2][9] So retinoic acid is an endogenous signal that maintains the bilateral synchrony of mesoderm segmentation and controls bilateral symmetry in vertebrates. The bilaterally symmetric body plan of vertebrate embryos is obvious in somites and their derivates, such as the vertebral column. Therefore, asymmetric somite formation correlates with a left-right desynchronization of the segmentation oscillations.[10]

Many studies with Xenopus and zebrafish have analyzed the factors of this development and how they interact in signaling and transcription. However, there are still some doubts in how the prospective mesodermal cells integrate the various signals they receive and how they regulate their morphogenic behaviours and cell-fate decisions.[8] Human embryonic stem cells for example have the potential to produce all of the cells in the body and they are able to self-renew indefinitely so they can be used for a large-scale production of therapeutic cell lines. They are also able to remodel and contract collagen and were induced to express muscle actin. This shows that these cells are multipotent cells.[11]

Intermediate mesoderm

The intermediate mesoderm connects the paraxial mesoderm with the lateral plate mesoderm, and differentiates into urogenital structures.[12] In upper thoracic and cervical regions, this forms the nephrotomes. In caudal regions, it forms the nephrogenic cord. It also helps to develop the excretory units of the urinary system and the gonads.[4]

Lateral plate mesoderm

The lateral plate mesoderm splits into the parietal (somatic) and visceral (splanchnic) layers. The formation of these layers starts with the appearance of intercellular cavities.[12] The somatic layer depends upon a continuous layer with mesoderm that covers the amnion. The splanchnic layer depends upon a continuous layer that covers the yolk sac. The two layers cover the intraembryonic cavity. The parietal layer, together with overlying ectoderm, forms the lateral body wall folds. The visceral layer forms the walls of the gut tube. Mesoderm cells of the parietal layer form the mesothelial membranes or serous membranes, which line the peritoneal, pleural, and pericardial cavities.[1][2]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Ruppert, E.E.; Fox, R.S.; Barnes, R.D. (2004). "Introduction to Bilateria". Invertebrate Zoology (7th ed.). Brooks/Cole. pp. 217–218. ISBN 978-0-03-025982-1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Langman's Medical Embryology, 11th edition. 2010.

- ↑ Kimelman, D. & Bjornson, C. (2004). "Vertebrate Mesoderm Induction: From Frogs to Mice". In Stern, Claudio D. (ed.). Gastrulation: from cells to embryo. CSHL Press. p. 363. ISBN 978-0-87969-707-5.

- 1 2 3 Scott, Gilbert (2010). Developmental biology (ninth ed.). US: Sinauer Associates.

- ↑ Dudek, Ronald W. (2009). High-yield. Embryology (4th ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- ↑ "Paraxial Mesoderm: The Somites and Their Derivatives". National Center for Biotechnology Information. Retrieved April 15, 2013.

- ↑ Drew, Ulrich (1993). Color atlas of embryology. German: Thieme.

- 1 2 3 Yusuf, Faisal (2006). "The eventful somite: Patterning, fate determination and cell division in the somite". Anatomy and Embryology. 211 Suppl 1: 21–30. doi:10.1007/s00429-006-0119-8. PMID 17024302. S2CID 24633902. ProQuest 212010706.

- ↑ Cunningham, T.J.; Duester, G. (2015). "Mechanisms of retinoic acid signalling and its roles in organ and limb development". Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 16 (2): 110–123. doi:10.1038/nrm3932. PMC 4636111. PMID 25560970.

- ↑ Vermot, J.; Gallego Llamas, J.; Fraulob, V.; Niederreither, K.; Chambon, P.; Dollé, P. (April 2005). "Retinoic acid controls the bilateral symmetry of somite formation in the mouse embryo" (PDF). Science. 308 (5721): 563–566. Bibcode:2005Sci...308..563V. doi:10.1126/science.1108363. PMID 15731404. S2CID 5713738. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- ↑ Boyd, N.L.; Robbins KR, K.R.; Dhara SK, S.K.; West FD, F.D.; Stice SL., S.L. (August 2009). "Human embryonic stem cell-derived mesoderm-like epithelium transitions to mesenchymal progenitor cells". Tissue Engineering. Part A. 15 (8): 1897–1907. doi:10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0351. PMC 2792108. PMID 19196144.

- 1 2 Kumar, Rani (2008). Textbook of human embryology. I.K. International.

Further reading

- Gurdon, J.B. (1995). "The formation of mesoderm and muscle in Xenopus". In Zagris, Nikolas; et al. (eds.). Organization of the early vertebrate embryo. Springer. ISBN 978-0-306-45132-4.

- Kenderew, John Cowdery; Lawrence, Eleanor, eds. (1994). "Mesoderm Induction". The encyclopedia of molecular biology. John Wiley & Sons. p. 541. ISBN 978-0-632-02182-6.

- Liu, Shu Q. (2007). "Early Embryonic Organ Development". Bioregenerative engineering: principles and applications. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-70907-7.

- McGeady, Thomas A.; et al. (2006). "Establishment of the Basic Body Plan". Veterinary embryology. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-1147-8.

- Pappaioannou, Virginia, E. (2004). "Early Embryonic Mesoderm Development". In Lanza, Robert Paul (ed.). Handbook of stem cells, Volume 1. Gulf Professional Publishing. ISBN 978-0-12-436642-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Sherman, Lawrence S.; et al., eds. (2001). Human embryology (3rd ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 978-0-443-06583-5.