The Parliament of 1614 was the second Parliament of England of the reign of James VI and I, which sat between 5 April and 7 June 1614. Lasting only two months and two days, it saw no bills pass and was not even regarded as a parliament by its contemporaries. However, for its failure it has been known to posterity as the Addled Parliament.[lower-alpha 1]

James had struggled with debt ever since he came to the English throne. The failure of the Blessed Parliament of 1604–1610, in its six-year sitting, to rescue the king from his mounting debt or allow James to unite his two kingdoms, had left him bitter with the body. The four-year hiatus between parliaments saw the royal debt and deficit grow further, despite the best efforts of Treasurer Lord Salisbury. The failure of the last and most lucrative financial expedient of the period, a foreign dowry from the marriage of his heir-apparent, finally convinced James to recall Parliament in early 1614.

The parliament got off to a bad start, with poor choices made for the king's representatives in Parliament. Rumours of conspiracies to manage Parliament (the "undertaking") or to pack it with easily-controlled members, though not based in fact, spread quickly. The spreading of that rumour and the ultimate failure of Parliament have been generally attributed to the scheming of the crypto-Catholic Earl of Northampton, but that allegation has met with some recent skepticism. Parliament opened on 5 April and, despite the king's wishes it would be a "Parliament of Love", flung itself immediately into the controversy over the conspiracies, which split Parliament and led to the exclusion of one alleged packer. However, by late April, Parliament had moved on to a familiar controversy, that of impositions. The House of Commons were pitted against the House of Lords, culminating in a controversy over an unrestrained speech by one prelate.

James grew impatient with the parliamentary proceedings. He issued an ultimatum to Parliament, which treated it irreverently. Insult was added to injury by belligerent and supposedly-threatening attacks on him from the Commons. On the advice of Northampton, James dissolved Parliament on 7 June and had four Members of Parliament (MPs) sent to the Tower of London. James devised new financial expedients to settle his still-growing debt, with little success. Historiographically, historians are divided between the Whiggish view of the parliament as anticipating the constitutional disputes of future parliaments and the revisionist view of it as a conflict primarily concerned with James's finances.

Background

.jpg.webp)

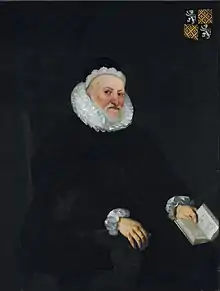

James VI and I (1566–1625) ascended to the Scottish throne on 24 July 1567, and subsequently to the English and Irish throne on 24 March 1603, becoming the first king to reign over both kingdoms.[3] James inherited, with the latter throne, a national debt to the amount of £300,000, a sum that only increased during his reign. By 1608, it stood at £1 million. During his predecessor Elizabeth I's reign, the inward revenue of the crown had steadily fallen; taxes from customs and land were consistently undervalued and the parliamentary subsidies steadily shrank.[3] It did not help that James reigned as "one of the most extravagant kings" in English history.[4] In peace, Elizabeth's yearly expenditure never rose above £300,000; almost immediately after James took the throne, it was at £400,000.[4] James had instituted various extra-parliamentary plans to recuperate this lost income, but these drew controversy from Parliament, and James still wanted money.[3] Moreover, James was keen to not be "a husband to two wives" as king, and to unite his crowns as one kingdom of Great Britain;[5] as his slogan went: "one king, one people, and one law".[6][lower-alpha 2] The first parliament of his reign, also known as the Blessed Parliament, was called in 1604; it took seven years, with proceedings held through five sessions, before James dissolved it,[5] ending unsatisfactorily for both king and Parliament.[7] In the first session, it came to light that many members of the Commons feared James's proposed unification would lead to the dissolution of the English Common Law system. Though many prominent politicians publicly praised the idea of unification and MPs promptly accepted a commission to investigate the union, James's proposed adoption of the title "king of Great Britain" was rejected outright.[3][5] Between the first and second sessions, in October 1604, James assumed this title by proclamation, controversially circumventing Parliament. Unification was not brought up at the second session, in hopes of assuaging outrage,[5] but discussions of the plans in the third session were exclusively negative; as Scottish historian Jenny Wormald put it, "James's union was killed by this parliament".[3] Unification was quietly dropped from discussion in the fourth and fifth sessions.[5]

During the Blessed Parliament, Parliament's own aims saw similar disappointment; James rebuffed the proposed institution of Puritan ecclesiastical reforms,[5] and failed to address two unpopular royal rights, purveyance and wardship.[3][lower-alpha 3] In the second session, Parliament granted the king a subsidy of £400,000, keen to exhibit royal support in the wake of the Gunpowder Plot,[5] but thanks to the reduction of these subsidies under Elizabeth, this was rather less than the king desired.[3] After a three-year delay between sessions due to plague, the fourth session was called in February 1610, and was dominated by financial discussion. Lord High Treasurer, Robert Cecil, 1st Earl of Salisbury proposed the Great Contract: a financial plan wherein Parliament would grant the Crown £600,000 immediately (to pay off its debts) and an annual stipend of £200,000 thereafter; in return, the king was to abolish ten feudal dues, among them, purveyance. After much haggling, in which wardship was added to the abolished dues, the session adjourned on a supportive note. However, when the next session began, support had cooled. Parliament refused to give an annual stipend unless James abolished impositions as well.[lower-alpha 4] Parliament did give the king an immediate subsidy, but the proposed £600,000 was reduced to a mere £100,000. By 6 November 1610, James demanded the other £500,000 and conditioned that, if impositions were to be abolished, Parliament would have to supply him with another equally lucrative income source. Parliament was outraged, and the Contract was abandoned three days later. Though both Salisbury and James made conciliatory gestures in hopes of securing any more financial support from Parliament, James grew impatient. On 31 December 1610, James publicly proclaimed the dissolution of the Parliament.[5] James's first parliament had ended on a bitter note; "your greatest error", he chastised Salisbury, "hath been that ye ever expected to draw honey out of gall."[10]

After this, James was not keen to call another Parliament.[11][12] However, without Parliament to raise taxes, the treasury was forced to find new ways to raise money.[11][7] In 1611, the City of London loaned the Crown £100,000; £60,000 was extracted from the King of France over debts accumulated in the reign of Henry IV; honours were sold to wealthy gentlemen, raising £90,000; a forced loan was levied on nearly 10,000 people.[13] Yet, after the death of Treasurer Salisbury in 1612, England's finances still remained destitute, with a debt of £500,000 and annual deficit of £160,000.[14][15] However, James's principal fiscal expedient was to be the marriage of his heir-apparent, Henry, Prince of Wales, for which he expected a sizeable dowry,[11] not to mention a foreign ally.[16] James went into talks with several Catholic countries but, in late 1612, aged 18, Henry contracted typhoid and abruptly died;[17] Prince Charles, newly heir-apparent at age 12, took his place in the negotiations. Negotiations were going most promisingly in France, where a marriage of Prince Charles to the 6-year-old Princess Christine of France promised a healthy sum of £240,000, almost halving James's debt.[8] However, by early 1614, France's internal religious strife had intensified to such a point that civil war seemed imminent, so negotiations stalled on the French side; James grew impatient.[11] James's financial insecurity had only worsened in this time, the debt now at £680,000 and the deficit, £200,000.[18] Conspicuous consumption had raised yearly expenditure to an unsustainable £522,000.[19] A group of advisors, led by the Earls of Suffolk and Pembroke, encouraged the king to call a parliament to raise funds, convincing James "that"—as he later put it—"my subjects did not hate me, which I know I had not deserved."[8] Suffolk and Pembroke, though not optimistic about the parliament, encouraged James as they held what was then the general view in the Privy Council: that a Spanish or French alliance must be avoided, as to avoid strengthening the power of their allies in Court, the Scots.[11] Northampton stringently opposed this summoning,[20] but, in 1614, James reluctantly summoned another parliament. Writs of election were issued on 19 February that year.[11]

Parliament

Preparations

The Privy Council as a whole was not optimistic about the upcoming parliament. Two of the king's closest advisors were unavailable: Salisbury was dead and the 74-year-old Northampton was ill.[8] Even Suffolk and Pembroke were clueless of any way to prevent Parliament from bringing up thorny issues such as impositions again.[11] However, two Councillors were to provide advice to the king over his new parliament, which would prove significant.[12] Attorney General Sir Francis Bacon, who had been among the most vocal in favour of calling Parliament, publicly blamed Salisbury entirely for the failure of the previous Parliament; he held a private grudge against the treasurer, suspecting he had undermined his early career. He asserted that Salisbury's deal-making with Parliament had been the root of the king's failure, and that James should instead approach Parliament as their king, rather than some merchant, and therefore request subsidies on the basis of the Commons' goodwill to their ruler.[21][22] Bacon added to this that the king should employ patronage to win over the men of Parliament to his side.[23] Sir Henry Neville offered advice to the king on how to warm relations with Parliament, which he accepted amiably,[24] but Neville's more portentous offer was that of an "undertaking", whereby Neville and a group of "patriots" would arrange to manage the Parliament in James's favour, in return for the office of Secretary of State.[25] James rejected the undertaking derisively, and no such conspiracy was ever arranged,[25] but rumours of its actual occurrence spread quickly in the lead up to Parliament.[26]

MPs later accused James of trying to pack the parliament.[11][27] Indeed, Bacon had plainly advised the king on the "placing of persons well-affected and discreet" in Parliament,[25][28] and James had unapologetically packed the Irish Parliament the previous year.[29][lower-alpha 5] An atypically large number of Crown officials found themselves in this parliament;[31] four Privy Councillors had seats in the Commons, alongside plenty of Crown lawyers.[32] Though there is no evidence that the Crown sought to pack Parliament with easily controlled and pacified MPs, James certainly promoted the election of those sympathetic to the Crown's ambitions.[31] The Privy Council, in actuality, seemed more apathetic with regard to appointing useful parliamentary officials. Few of the expected preparations were made.[8] After some Byzantine wrangling in which another better-qualified candidate was dropped, Ranulph Crewe, judge and MP for the government-controlled borough of Saltash, was chosen at the last minute to be the Speaker of the House of Commons.[33] This was a surprising choice: Crewe's previous experience in Parliament was limited to a short stint as an MP in 1597–98 and an appearance on two minor legal counsels; his legal career was no more impressive.[34] Crewe's inexperience at dealing with rowdy MPs was no doubt among the factors that allowed Parliament to descend into disorder, as it rapidly did.[35] James's most senior representative in the House of Commons, Ralph Winwood, Secretary of State, was announced similarly late. Though a spirited official and zealous Puritan, Winwood had no parliamentary experience at all and was a terse, unlikable figure.[8][36] Though sometimes caricatured as juvenile, and thus prone to passionate outbursts, the new House of Commons as a whole was not especially young or inexperienced;[lower-alpha 6] it was the inexperience of his most important officials and advisors that was to damage the king.[37]

Opening and conspiracies

Parliament opened on 5 April 1614.[11] James opened the Parliament with the wish that it would come to be known as the "Parliament of Love", and that king and Parliament would go on in harmony and understanding.[38] His opening speech was divided into three sections: the first (bona animi), decrying the growth of Catholicism and imploring the harsher enforcement of existing laws;[lower-alpha 7] the second (bona corporis), assuring Parliament of the security of the Stuart dynasty; and the third (bona fortunae), emphasising his financial necessity, and his aim not to bargain with Parliament any longer, but rather to ask of their goodwill in supplying funds.[40][41] All but the religious aspect of this speech bore the unmistakable stamp of Bacon's influence.[42] Notably missing from the speech was any promise of compromise or reformation from the king.[43] In the same speech, he stringently denied any sanction of Neville's undertaking,[38] but speculation on the conspiracy was already widespread.[11] Neville's plan had, by now, been twisted into a far-reaching conspiracy of the king's court.[43] English diplomat Sir Thomas Roe was the first to allege that the rumours were promulgated by the Earl of Northampton's crypto-Catholic faction, who wanted the king to instead look for funds in a marital alliance with Catholic Spain, thus favouring Parliament's failure.[11][26] The idea that Northampton masterminded many of the factors in the failure of this parliament has been accepted by most later historians,[44] but has met with the notable rejection of one Northampton biographer, Linda Levy Peck.[45]

Suspicions only compounded as Parliament proceeded, with the revelation that the king had corresponded with influential subjects in the hopes of securing the election of the sympathetic.[43] The House of Commons was divided between those who accepted the conspiracy and those who rejected it.[11] The Commons thus immediately set about investigating the preceding elections for signs of misconduct.[46] Though little beyond this was established, it was found that the Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, Sir Thomas Parry, had swayed the election in Stockbridge. For a brief period, this investigation dominated the Commons: Parry was suspended from the House and, passingly, from his Chancellorship. For many in Parliament, this seemed evidence enough that the king's officials had attempted to pack Parliament.[11][46][47] Simultaneously, a committee to inquire into the alleged undertaking was launched, though this proved less fruitful. The committee's chairman returned on 2 May; he spoke confusingly, but concluded against the existence of any undertaking. However, parliamentary provocateur John Hoskins demanded further investigation, which the House accepted.[48] On 14 May, the inquiry ended; after six weeks of Parliament, rumours of an undertaking had conclusively been dismissed.[11][48] However, by the end of this controversy, resentment against the undertakers had evaporated. Neville was never suspended for his part, but rather ultimately met with commendation of Parliament. His advice was seen as part of an effort to allow the king to remedy their grievances. The packers, on the other hand, never gained the sympathy of Parliament, with their efforts invariably seen as attempts to undermine the parliamentary process.[49]

Controversy over impositions

My Lords, I think it a dangerous thing for us to confer with them about the point of impositions. For it is a Noli me tangere, and none that have either taken the Oath of Supremacy or Allegiance may do it with a good conscience, for in the Oath of Allegiance we are sworn to maintain the privileges of the Crown, and in this conference we should not confer about a flower, but strike at the root of the Imperial Crown, and therefore in my opinion it is neither fit to confer with them nor give them a meeting.

Bishop Neile, The "Noli me tangere speech", given to the House of Lords on 21 May.[50]

The dispute over the alleged packing and undertaking split the House, but it was not this that would cause the parliament's ultimate failure.[51] As early as 19 April, letter writer John Chamberlain communicated that "the great clamor against undertakers [was] well quieted",[52] and the Commons were occupied with a familiar controversy: impositions.[11][52] Parliament adjourned on 20 April for Easter, reconvening on 2 May.[11] Two days later on 4 May, the king delivered a speech to the Commons, ardent in its defence of the legality of impositions, a fact the king's judges had apparently assured him of beyond any doubt.[46] At the end he added portentously that, if he did not receive supply soon, the Commons "must not look for more Parliaments in haste".[53] However, at the same time, the Commons were united and unflinching in their belief that impositions threatened property law, and that, over impositions, "the liberty of the kingdom is in question."[29] James was so irritated by one such speech, given by MP Thomas Wentworth, that he had Wentworth imprisoned shortly after Parliament ended.[54] As parliamentary historian Conrad Russell judged it, "both sides were so firmly convinced that they were legally in the right that they never fully absorbed that the other party thought differently."[29] Any understanding between the two sides was further hampered by the fact that the Commons continued to disregard the king's financial troubles, which discouraged the king from giving up such a valuable source of income as impositions.[29]

On 21 May, the Commons asked the Lords for a conference on impositions, anticipating their backing in petitioning the king. After five days of debate, the Lords returned with their formal refusal of such a conference, meeting with the astonishment of many.[11] The Lords had voted 39 to 30 against it, carried by the near unanimity of the Lords Spiritual against this conference.[lower-alpha 8][54] Bishop Richard Neile, who was one of the most vocal opponents of the conference,[55] added insult to injury with a sharp speech condemning the petitioners.[46] The remarks made in this speech, known as the "Noli me tangere speech", have been described by one historian as "the most dangerous words used in the reign [of James I] by any politician."[56] The Commons refused to conduct any more business until Neile had been punished for this affront.[11] Crewe's feeble attempts to argue that parliamentary business must go on revealed his impotence in the face of the angered body.[34] Though the Commons received a tearful apology and retraction from the Bishop on 30 May, they were unsatisfied and doubled down on their demands of disciplinary action.[57] By the end of May, as historian Thomas L. Moir put it, "the temper of the Commons had reached a fever pitch"[58] and leadership had broken down in this intractable atmosphere.[59] No punishment for Neile, however, ever materialised, and the king grew impatient with Parliament.[11]

James grows impatient

Parliament was adjourned on 1 June for Ascension Day, reconvening again on 3 June.[11] When the Commons met on this day, they received an ultimatum from the king: unless Parliament agreed to grant him a financial supply soon, he would dissolve Parliament on 9 June.[60] James expected this to shock the Commons into pursuing his aims, but instead, it only entrenched the opposition further into its obstinacy. Many felt this demand was a bluff; the king was still deeply in debt, and parliamentary subsidies seemed his only way out. Instead of effecting any subsidies, the Commons attacked the king mercilessly. His Court, especially its Scottish members, were accused of extravagance, suggesting the king would have no need for impositions or subsidies if not for these subjects.[11] As one member memorably pronounced, James's courtiers were "spaniels to the king and wolves to the people".[61] Possibly encouraged by Northampton,[lower-alpha 9] Hoskins grimly hinted that the lives of these Scottish courtiers were in danger, alluding to the ethnic massacre of the Angevins in the Sicilian Vespers; this was communicated to the king as a threat to the life of himself and his closest friends, such that he likely feared himself in danger of assassination.[64] Roe was more prescient, if somewhat melodramatic, in his judgement that the impending dissolution would be "the ending, not only of this, but of all Parliaments".[53] The Commons issued their own ultimatum to James: if he abolished impositions, "wherewith the whole kingdom doth groan", they would give him financial support.[11]

However, James was in no position to give up such a source of income.[11] While the anti-Northampton faction pleaded with the king to prorogue rather than dissolve Parliament, the king visited Northampton on his deathbed. Northampton persuaded the desperate king to dissolve Parliament. Shortly after James contacted the Spanish Ambassador, the Count of Gondomar, to be assured of Spanish support after his break with Parliament, an assurance which Gondomar happily supplied. James dissolved Parliament on 7 June 1614. The aims of Northampton's factions were finally fulfilled, as Northampton saw the end of the Addled Parliament little more than a week before he died.[11][64] The Parliament had elapsed without any bill being passed with royal assent, and thus was not constitutionally considered a parliament. Contemporaries spoke of it as a "convention". For John Chamberlain, it seemed "rather a parlee only".[11][61][65] However, for its failure the parliament has universally been known to posterity as the "Addled Parliament".[11]

Aftermath

The House of Commons is a body without a head. The members give their opinions in a disorderly manner. At their meetings nothing is heard but cries, shouts, and confusion. I am surprised that my ancestors should ever have permitted such an institution to come into existence. I am a stranger, and found it here when I arrived, so that I am obliged to put up with what I cannot get rid of.

James I's remarks to Gondomar, the Spanish Ambassador, a few days after the dissolution.[66]

Following the calamity of this parliament, James became even more determined to avoid the legislative body.[67] He had four of the most belligerent MPs, including Hoskins, sent to the Tower of London for seditious speech. The same was done for Hoskins's encouragers a few days later.[68] Royal favour was extended to the king's supporters in Parliament, even the Speaker, who received a knighthood and was made a king's serjeant.[69][34] Simultaneously, James approached the Spanish Ambassador shortly after Parliament, confiding much in him, especially regarding his lack of confidence with Parliament.[64] He reopened negotiations with Spain for a Spanish wife to his heir-apparent, anticipating a dowry of £600,000, enough to cover almost all his debt.[67][64]

Shortly after the parliament ended, the Privy Council went into talks of calling another, possibly in Scotland,[3] but James surmised this break in Parliament would be final.[64] Indeed, he would not call another parliament for seven years. He only raised a Parliament in 1621 as a last resort to raise money for his son-in-law Elector Palatine Frederick V during the Thirty Years' War.[67] This interlude was England's longest in nearly a century, since that between 1515 and 1523.[70] As one historian has commented, "had it not been for the outbreak of the Thirty Years’ War in 1618, he might have succeeded in avoiding Parliament for the rest of his reign."[53] In the meantime, still heavily in debt, James set about finding other ways to raise money. "We shall see strange projects for money set on foot, and yet all will not help", one observer noted.[71] His financial needs were temporarily sated with a benevolence asked of his wealthiest subjects in 1614, raising £65,000;[72] the sale of the Cautionary Towns of Brielle and Vlissingen to the Dutch in 1616, raising £250,000;[73] and in 1617, the request of a loan of £100,000 from the City of London for a Scottish Progress, though the City did not give this in full.[74] The deficit was slowly reduced from 1614 to 1618.[75] Yet, by 1620, his debt had risen to £900,000 and no marriage deal had materialised.[3]

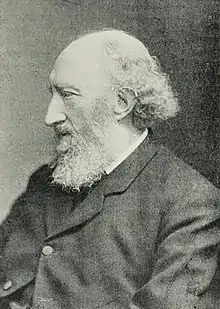

Historiography

Victorian Whig historian Samuel Rawson Gardiner, in his monumental history of the lead-up to the Civil War, took the view that the parliament of 1614 was primarily concerned with "higher questions" (i.e. those of a constitutional nature) "which, once mooted, can never drop out of sight".[76][77] To this parliament, Gardiner wrote, one can "trace the first dawning of the idea that, in order to preserve the rights of the subject intact, it would be necessary to make some change in the relations between the authority of the Crown and the representatives of the people."[78] Gardiner's judgement of the constitutional import of this assembly has met with the sympathy of some later historians.[79] Moir, in his 1958 monograph on the parliament, held that "the development had begun which led ultimately to parliamentary control of the executive" as early as the exclusion of Parry.[79] Maija Jansson, editor of the 1614 Parliamentary proceedings, wrote in 1988: "[f]ar from being the confused do-nothing assembly of tradition, the English parliament of 1614 addressed thorny constitutional issues and anticipated the concern with procedure and privilege that is evident throughout the sessions of the 1620s."[80]

This hypothesis regarding the Addled Parliament was criticised by the eminent parliamentary historian Conrad Russell in his 1991 Stenton lecture—entitled The Addled Parliament of 1614: The Limits of Revision.[81] From Russell's revisionist perspective, the members of Parliament were engaged in a constitutionally conservative battle, aimed at preserving their own rights rather than extending them. The disagreement between Parliament and Crown was not a "battle between rival constitutional ideas"[81] but, as Russell concluded:

The central disagreement of James's reign was about the true [monetary] cost of government, and James’s central failure was his failure to convince the House of Commons he needed as much as in fact he did. From that single failure, all the constitutional troubles of the reign stemmed.[81]

See also

Notes

- ↑ The nickname first appears in the form "addle parliament" in a letter of Reverend Thomas Lorkin to Sir Thomas Puckering, an English correspondent abroad in Madrid, little more than a week after the parliament dissolved. The form "Addled" first appears in the middle of the 19th century. "Addle" is an adjective denoting (of an egg) "rotten" or "putrid" and more generally anything "empty, idle, vain; muddled, confused, unsound". Some sources connect the parliament's nickname to the former definition, the historian J. A. Williamson, for example, noting, "It was called the Addled Parliament, since it had hatched nothing".[1][2]

- ↑ In James's original Latinism: "Unus Rex [...] Unus Grex and Una Lex".[6]

- ↑ According to Andrew Thrush of The History of Parliament: "Purveyance was the right of the Crown to take up provisions for the royal household at below the market rate, while wardship was the right of the Crown to manage the estates of minors whose lands were held of the king."[5]

- ↑ The feudal duty of impositions was an invaluable source of extra-parliamentary income for James, especially as trade expanded in England during his reign. By 1610, they already brought the Crown around £70,000 a year; by the 1630s, they brought in no less than £218,000.[8][9]

- ↑ James attempted to pack the Irish Parliament of 1613 with Protestants by adding 84 new seats to the former 148 that election: 38 represented tiny or as-yet nonexistent settlements in the Protestant Ulster plantation. The election came out with a Protestant majority of 32. James insisted he was within his royal right in doing this and mocked the parliament's anger at this.[30]

- ↑ 61% (281 out of 464) of the members had never sat in Parliament before, a little above the Elizabethan average of 50%, but perfectly reasonable given the decade-long interval between elections.[37]

- ↑ According to historian Thomas L. Moir, this aspect of James's speech "displayed one of those flashes of visions which occasionally revealed his intellectual capacity."[39] Rather than demand the institution of new anti-Catholic legislature, James contended that persecution only aided the Catholic cause, and that, as Protestantism was correct, it could reject Catholicism for its own fallacies. Such an ostensibly tolerant doctrine was a novelty in James's time.[39]

- ↑ Out of the 17 prelates who voted, all but one opposed the conference, namely the old-fashioned Archbishop of York, Tobias Matthew.[54]

- ↑ According to Moir, Hoskins here "seems to have been simply the tool of the pro-Spanish [i.e. Northampton's] interests."[62] The provocative historical reference was submitted by two of Northampton's lackeys: Lionel Sharpe, Sir Charles Cornwallis. Gardiner alleges he was not the most historically learned member, and likely misunderstood the insinuation in the reference. Hoskins was also promised the protection of Northampton (and possibly Somerset) if he was to be charged with sedition, and was perhaps encouraged by a £20 bribe.[62] This allegation has been questioned by Peck, who asserts that Hoskyns' misunderstanding of the allusion was "unlikely" given his educational background, and Hoskyns was already a known opponent of Scottish influence. Thus, in her view: "it seems more reasonable to view Hoskyns not as the innocent tool or victim of the pro-Spanish interests, but as a member of the Commons who agreed with the idea of sending home the Scots".[63]

References

- ↑ OED, "addle".

- ↑ OED, "addled".

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Wormald 2014.

- 1 2 Russell 1973, p. 98.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Thrush 2010a.

- 1 2 Croft 2003, p. 59.

- 1 2 Mathew 1967, p. 221.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Croft 2003, p. 92.

- ↑ Russell 1990, p. 39.

- ↑ Croft 2003, p. 80.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 Thrush 2010b.

- 1 2 Stewart 2011, p. 251.

- ↑ Dietz 1964, pp. 148–149.

- ↑ Dietz 1964, p. 149.

- ↑ Moir 1958, p. 10.

- ↑ Croft 2003, p. 84.

- ↑ Croft 2003, p. 85.

- ↑ Roberts 1985, p. 7.

- ↑ Russell 1973, pp. 98–99.

- ↑ Cramsie 2002, p. 135.

- ↑ Willson 1967, pp. 344–345.

- ↑ Stewart 2011, pp. 251–252.

- ↑ Duncan & Roberts 1978, p. 489.

- ↑ Thrush 2010c.

- 1 2 3 Duncan & Roberts 1978, p. 481.

- 1 2 Duncan & Roberts 1978, p. 491.

- ↑ Moir 1958, p. 52.

- ↑ Mathew 1967, pp. 221–222.

- 1 2 3 4 Croft 2003, p. 93.

- ↑ Croft 2003, p. 93, 148.

- 1 2 Moir 1958, p. 53.

- ↑ Mathew 1967, pp. 222–223.

- ↑ Moir 1958, pp. 41–42.

- 1 2 3 Hunneyball 2010.

- ↑ Smith 1973, p. 169.

- ↑ Willson 1967, p. 345.

- 1 2 Moir 1958, p. 55.

- 1 2 Mondi 2007, p. 153.

- 1 2 Moir 1958, p. 81.

- ↑ Mathew 1967, p. 226.

- ↑ Moir 1958, pp. 80–82.

- ↑ Moir 1958, p. 82.

- 1 2 3 Willson 1967, p. 346.

- ↑ Peck 1981, p. 533: "Northampton was accused by some contemporaries and most later historians of engineering the abrupt dissolution of the Addled Parliament in 1614".

- ↑ Peck 1981, p. 535: "Secondly, the one thing that every schoolboy knows about Northampton - that he destroyed the Addled Parliament of 1614 - might be questioned".

- 1 2 3 4 Willson 1967, p. 347.

- ↑ Seddon 2008.

- 1 2 Duncan & Roberts 1978, p. 492.

- ↑ Roberts 1985, p. 29.

- ↑ Moir 1958, p. 117.

- ↑ Duncan & Roberts 1978, pp. 496–497.

- 1 2 Duncan & Roberts 1978, p. 497.

- 1 2 3 Thrush 2014.

- 1 2 3 Mathew 1967, p. 227.

- ↑ Moir 1958, pp. 116–117.

- ↑ Mathew 1967, p. 228.

- ↑ Moir 1958, pp. 130–131.

- ↑ Moir 1958, p. 132.

- ↑ Moir 1958, pp. 132–133.

- ↑ Moir 1958, p. 136.

- 1 2 Mathew 1967, p. 229.

- 1 2 Moir 1958, p. 140.

- ↑ Peck 1981, p. 550.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Willson 1967, p. 348.

- ↑ Croft 2003, pp. 93–94.

- ↑ Gardiner 1883, p. 251.

- 1 2 3 Thrush 2010d.

- ↑ Moir 1958, p. 146.

- ↑ Moir 1958, p. 148.

- ↑ Mondi 2007, p. 140.

- ↑ Dietz 1964, pp. 158–159.

- ↑ Croft 2003, p. 94.

- ↑ Croft 2003, p. 95.

- ↑ Croft 2003, p. 100.

- ↑ Moir 1958, p. 153.

- ↑ Clucas & Davies 2003, p. 1.

- ↑ Gardiner 1883, p. 228.

- ↑ Gardiner 1883, p. 240.

- 1 2 Russell 1990, p. 31.

- ↑ Jansson 1988, p. xiii.

- 1 2 3 Clucas & Davies 2003, p. 2.

Sources

- Clucas, Stephen; Davies, Rosalind (2003). "Introduction". In Clucas, Stephen; Davies, Rosalind (eds.). The Crisis of 1614 and The Addled Parliament: Literary and Historical Perspectives (1st ed.). Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7546-0681-9.

- Cramsie, John (2002). Kingship and Crown Finance under James VI and I, 1603–1625. Royal Historical Society Studies in History (New Series). Suffolk: The Boydell Press. ISBN 978-0-86193-259-7.

- Croft, Pauline (2003). King James. Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9780333613955. OCLC 938114859.

- Dietz, Frederick C. (1964). English Public Finance, 1558–1641. English Public Finance, 1485–1641. Vol. 2 (2nd ed.). New York: Barnes & Noble, Inc. OCLC 22976184.

- Duncan, Owen; Roberts, Clayton (July 1978). "The Parliamentary Undertaking of 1614". The English Historical Review. 93 (238): 481–498. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.698.3301. doi:10.1093/ehr/xciii.ccclxviii.481. JSTOR 565464.

- Gardiner, Samuel R. (1883). History of England from the Accession of James I to the Outbreak of the Civil War, 1603–1642. Vol. II. 1607–1616. London: Longmans, Green, and Co. OCLC 4088221.

- Hunneyball, Paul (2010). "CREWE, Ranulphe (1559-1646), of Lincoln's Inn, London and Crewe Hall, Barthomley, Cheshire; later of Westminster". In Ferris, John P.; Thrush, Andrew (eds.). The House of Commons, 1604-1629. The History of Parliament. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Jansson, Maija (1988). "Introduction". In Jansson, Maija (ed.). Proceedings in Parliament, 1614 (House of Commons). Memoirs of the American Philosophical Society. Vol. 172. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society. pp. xiii–xxxvi. ISBN 978-0-87169-172-9.

- Mathew, David (1967). James I. Alabama: University of Alabama Press. ISBN 9780817354008. OCLC 630310478.

- Moir, Thomas L. (1958). The Addled Parliament of 1614. Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 1014344.

- Mondi, Megan (2007). "The Speeches and Self-Fashioning of King James VI and I to the English Parliament, 1604-1624". Constructing the Past. 8 (1): 139–182. OCLC 1058935115.

- "addle, n. and adj.". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. December 2020. Retrieved 3 February 2021. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- "addled, adj.". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. December 2020. Retrieved 3 February 2021. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- Peck, Linda Levy (September 1981). "The Earl of Northampton, Merchant Grievances and the Addled Parliament of 1614". The Historical Journal. 24 (3): 533–552. doi:10.1017/S0018246X00022500. JSTOR 2638882. S2CID 159485080.

- Roberts, Clayton (1985). Schemes & Undertakings: A Study of English Politics in the Seventeenth Century. Columbus: Ohio State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8142-0377-4.

- Russell, Conrad (1973). "Parliament and the King's Finances". In Russell, Conrad (ed.). The Origins of the English Civil War. London: Macmillan Press. doi:10.1007/978-1-349-15496-8. ISBN 978-0-333-12400-0.

- Russell, Conrad (1990). Unrevolutionary England, 1603–1642. London: The Hambledon Press. ISBN 978-1-85285-025-8.

- Seddon, P. R. (3 January 2008). "Parry, Sir Thomas (1544–1616), administrator". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/21434. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Smith, Alan G. R. (1973). "Constitutional Ideas and Parliamentary Developments in England 1603–1625". In Smith, Alan G. R. (ed.). The Reign of James VI and I. London: Macmillan Press. pp. 160–176. ISBN 9780333121610. OCLC 468638840.

- Stewart, Alan (2011). The Cradle King: A Life of James VI & I. London: Random House. ISBN 978-1-4481-0457-4.

- Thrush, Andrew (2010a). "The Parliament of 1604-1610". In Ferris, John P.; Thrush, Andrew (eds.). The House of Commons, 1604-1629. The History of Parliament. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Thrush, Andrew (2010b). "The Parliament of 1614". In Ferris, John P.; Thrush, Andrew (eds.). The House of Commons, 1604-1629. The History of Parliament. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Thrush, Andrew (2010c). "NEVILLE, Sir Henry I (1564-1615), of Billingbear, Waltham St. Lawrence, Berks. and Tothill Street, Westminster; formerly of Mayfield, Suss.". In Ferris, John P.; Thrush, Andrew (eds.). The House of Commons, 1604-1629. The History of Parliament. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Thrush, Andrew (2010d). "The Parliament of 1621". In Ferris, John P.; Thrush, Andrew (eds.). The House of Commons, 1604-1629. The History of Parliament. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Thrush, Andrew (7 May 2014). "1614: The Beginning of the Crisis of Parliaments". The History of Parliament blog. Archived from the original on 30 March 2020.

- Willson, David Harris (1967). King James VI and I. New York: Oxford University Press. OCLC 395478.

- Wormald, Jenny (25 September 2014). "James VI and I (1566–1625), king of Scotland, England, and Ireland". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/14592. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

Further reading

- Russell, Conrad (2011). King James VI and I and his English Parliaments. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-820506-7.

.svg.png.webp)