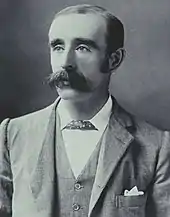

Paddy Glynn | |

|---|---|

| |

| Minister for Home and Territories | |

| In office 17 February 1917 – 3 February 1920 | |

| Prime Minister | Billy Hughes |

| Preceded by | Fred Bamford |

| Succeeded by | Alexander Poynton |

| Minister for External Affairs | |

| In office 24 June 1913 – 17 September 1914 | |

| Prime Minister | Joseph Cook |

| Preceded by | Josiah Thomas |

| Succeeded by | John Arthur |

| Attorney-General of Australia | |

| In office 2 June 1909 – 29 April 1910 | |

| Prime Minister | Alfred Deakin |

| Preceded by | Billy Hughes |

| Succeeded by | Billy Hughes |

| Member of the Australian Parliament for Angas | |

| In office 16 December 1903 – 13 December 1919 | |

| Preceded by | New seat |

| Succeeded by | Moses Gabb |

| Member of the Australian Parliament for South Australia | |

| In office 30 March 1901 – 16 December 1903 | |

| Preceded by | New seat |

| Succeeded by | Divided into single-member divisions |

| Member of the South Australian Parliament for North Adelaide | |

| In office 22 May 1897 – 1901 | |

| Preceded by | Arthur Harrold |

| Succeeded by | Hugh Denison |

| Member of the South Australian Parliament for North Adelaide | |

| In office 8 June 1895 – 25 April 1896 | |

| Preceded by | George Charles Hawker |

| Succeeded by | Arthur Harrold |

| Member of the South Australian Parliament for Light | |

| In office 21 April 1887 – 22 April 1890 | |

| Preceded by | David Moody |

| Succeeded by | James Wharton White |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 25 August 1855 Gort, County Galway, Ireland |

| Died | 28 October 1931 (aged 76) North Adelaide, South Australia |

| Nationality | •Irish •Australian |

| Political party | Free Trade (1901–06) Anti-Socialist (1906–09) Liberal (1909–17) Nationalist (1917–19) |

| Spouse |

Abigail Dynon

(m. 1897; died 1930) |

| Relations | Joseph Glynn (brother) |

| Children | 6 |

| Alma mater | Trinity College, Dublin |

| Occupation | Barrister |

Patrick McMahon Glynn KC (25 August 1855 – 28 October 1931) was an Irish-Australian lawyer and politician. He served in the House of Representatives from 1901 to 1919, and was a government minister under three prime ministers, as Attorney-General (1909–1910), Minister for External Affairs (1913–1914) and Minister for Home and Territories (1917–1920). Prior to entering federal politics, Glynn was involved in the drafting of the Constitution of Australia. Born in Ireland, he arrived in Australia in 1880 and served three terms in the South Australian House of Assembly, as well as a brief stint as Attorney-General of South Australia.

Early life

Glynn was born on 25 August 1855 in Gort, County Galway, Ireland. He was the third of eleven children born to Ellen (née Wallsh) and John McMahon Glynn; his father ran a large general store. His younger brother was Joseph Glynn.[1] Glynn received his initial schooling in Gort from the Sisters of Mercy. In 1869, he began boarding at Blackrock College on the outskirts of Dublin, where he won prizes in French, Latin and Greek. He left school in 1872 and began reading law, serving his articles of clerkship with a local solicitor James Blaquiere. Glynn enrolled at Trinity College Dublin, graduating Bachelor of Arts in 1878 and also attending the King's Inns in preparation for a career as a barrister. After a period in London at the Middle Temple he was called to the Irish Bar in April 1879.[1]

Move to Australia

In 1880, Glynn emigrated to Australia, initially settling in Melbourne. He struggled to find work as a barrister, but did find the time to publish a pamphlet on Irish nationalism. He eventually took up a position as a travelling salesman, selling life insurance and Singer sewing machines.[1]

Glynn moved to Kapunda, South Australia, in 1882 to open a branch of the Adelaide law firm Hardy & Davis. His aunt Grace Wallsh had migrated to South Australia in the 1860s and was a member of the Sisters of St Joseph of the Sacred Heart. In 1883 he became the editor of The Kapunda Herald, a position he would hold until 1891. Glynn was admitted to the rolls of the Supreme Court of Australia in 1883 and bought out his Adelaide partners in 1886. He moved to Adelaide himself in 1888 and established a practice on Pirie Street.[1]

South Australian politics

Glynn helped found the South Australian Land Nationalisation Society, and served as president of the South Australian branch of the Irish National League. He hosted the 1882 Australian tour of John Redmond, the leader of Irish Home Rulers. In 1887 Glynn's easy personal manners and prominence as an editor assisted him in his election to the South Australian House of Assembly as the member for Light.[1][2] In the chamber Glynn was an unwavering advocate of free trade, but his support of female suffrage and land nationalisation isolated him from his conservative colleagues.[1]

Glynn was defeated at the 1890 election and stood unsuccessfully for Light again at the 1893 election but returned to South Australian colonial politics in 1895 as the member for North Adelaide. With this victory, he became the first person in Australia to be elected under adult suffrage (whereby females had the right to vote). While he was defeated a year later at the 1896 election, he returned to parliament in a by-election for the seat of North Adelaide in 1897. Glynn briefly served as Attorney-General of South Australia in 1899 and remained in parliament until 1901.[1][2]

Constitutional convention

Glynn saw no merit in federation itself,[3] but evidently perceived an attractive affinity between the federalisation of the United Kingdom by Home Rule and the creation of a federation of the six Australian colonies. Glynn successfully stood as a candidate for the Convention that framed the Australian Commonwealth constitution in 1897–98. He was regarded as one of the ablest authorities in Australia on constitutional law. He made major contributions to Murray River water rights, and advocated standardisation of rail gauges and universal suffrage. He also contributed a reference to God in the preamble to the Australian Constitution. He unsuccessfully sought to have the Chief Justices of the Supreme Courts of the states made ex officio members of the projected High Court.[4] He protested the Constitution licensing the first Governor General to appoint a prime minister and cabinet prior to the first election as "opposed to all our notions of parliamentary government".[5]

In the struggle over question of Federation in Western Australia, Glynn with some deviousness secretly drafted a petition, signed by 28,000, which implored the British government to carve out of the goldfields a new colony, 'Auralia'. Such a new colony would not serve Federation but its possibility was judged by Federationist strategists as likely to induce some Western Australians to support joining the new Commonwealth.[6]

Federal politics

First federal election

In the lead up to the inaugural federal election, Glynn acted as the informal deputy leader of the Free Trade Party and managed the Free Trade election campaigns in South Australia and Western Australia, while Free Trade leader George Reid oversaw the rest of Australia.[7] As a result, Glynn was not only comfortably elected to the single statewide Division of South Australia but, together with Reid, he is said to have "created Australia's first national political campaign".

Government minister

At the 1903 election, the statewide constituency was abolished and Glynn was returned unopposed in the Division of Angas. He was re-elected on five further occasions, and was unopposed at three consecutive elections (1910, 1913 and 1914).

Despite his ties with Reid, Glynn was not offered a place in the Reid government (1904–1905). He joined the new Liberal Party after the 1909 "fusion" with the Protectionists, and subsequently served as Attorney-General under Alfred Deakin from 1909 to 1910. He returned to ministerial office in 1913 as Minister for External Affairs in the Cook government, holding the position until the government's defeat at the 1914 election. In 1917, the Liberals merged with Prime Minister Billy Hughes' National Labor Party, forming the Nationalist Party. Glynn's final ministerial post was as Minister for Home and Territories from 1917 until his defeat at the 1919 election. In that capacity he handled the Darwin rebellion of 1918.

Later life

.jpg.webp)

Glynn retired from politics in 1919, and died at North Adelaide in 1931. He married Abigail Dynon, who predeceased him, and was survived by two sons and four daughters.[8] He was a fine Shakespearian scholar; several of his literary papers were published, as were also various legal and political pamphlets.

Legacy

In 2016, the Australian Catholic University established a new public policy think tank based at its North Sydney campus, which was named the PM Glynn Institute.[9]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 O'Collins, Gerald (1983). "Glynn, Patrick McMahon (Paddy)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Vol. 9. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. pp. 30–32. ISSN 1833-7538. Retrieved 14 August 2022.

- 1 2 "Patrick (Paddy) McMahon Glynn KC". Former members of the Parliament of South Australia. Retrieved 21 November 2022.

- ↑ Coleman (2021), p. 152.

- ↑ Coleman (2021), p. 431.

- ↑ Coleman (2021), p. 422.

- ↑ Coleman (2021), p. 257.

- ↑ McGinn, W.G. (1989). George Reid. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press. ISBN 0-522-84373-5.

- ↑ Hourican, Bridget (2009). "Glynn, Patrick McMahon". Dictionary of Irish Biography. doi:10.3318/dib.003500.v1.

- ↑ "Catholic solutions to public policy problems: ACU launches PM Glynn Institute think tank". The Catholic Weekly. 20 October 2016. Retrieved 11 November 2019.

Further reading

- Simms, M., ed. (2001). 1901: The forgotten election. Brisbane: University of Queensland Press. ISBN 0-7022-3302-1.

- Henderson, A. (2019). Federation's Man of Letters: Patrick McMahon Glynn. Connor Court, Brisbane. ISBN 9781925826487.

- Coleman, William (2021). Their Fiery Cross of Union. A Retelling of the Creation of the Australian Federation, 1889-1914. Queensland: Connor Court.