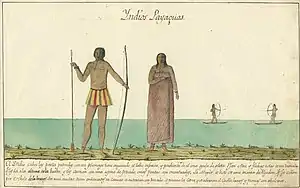

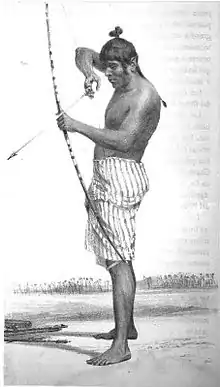

The Payaguá people, also called Evueví and Evebe, were an ethnic group of the Guaycuru peoples in the Northern Chaco of Paraguay. The Payaguá were a river tribe, living, hunting, fishing, and raiding on the Paraguay River. The name Payaguá was given to them by the Guaraní, their enemies whom they constantly fought. It is possible that the name of the Paraguay River, and thus the country Paraguay itself, comes from this; the Guaraní told the Spanish that the river was the "Payaguá-ý", or "river of Payaguás." The name they called themselves was probably Evueví, "people of the river" or "water people." The Payaguá were also known to early Spanish explorers as "Agaces" and spelling variations of that name.[2]

The Payagua language is extinct; they spoke a Guaycuruan language. No people remain who identify as Payaguá; the descendants of the tribe merged with other Paraguayans, either as mestizos or with other peoples, commonly called Indians.

The Payaguá were noted for their ferocity and their skill navigating the Paraguay River in their large dugout canoes. They were a serious threat to Spanish and Portuguese travel on the river from the early 16th until the late 18th century.

History

The Payaguá, inhabited the islands and shores of the Paraguay River, mostly north of the city of Asunción, but their travels took them as far north as the present-day city of Cuiabá, Brazil and as far south as present-day Argentina, a distance of 1,600 kilometres (990 mi).[3] They were an exception to the horse culture, in full flower by 1650, of other Guaycuruans. The Payagua plied the river in canoes, fished and gathered edible plants, and raided their agricultural neighbors, the Guaraní, to the east. Fear of the Payaguá drove the Guarani into the arms of the Spanish, a factor leading to the establishment among the Guarani of Roman Catholic missions, including the famous Jesuit reductions in Paraguay, Argentina, and Brazil.[4]

The Payaguá population at time of first contact with Europeans in the 16th and early 17th century has been variously estimated as between 6,000 and 24,000. As with most Indian peoples, their numbers declined due to the introduction of European diseases and by 1602 the Spanish were speaking of their diminished numbers.[5] Diminished numbers notwithstanding, the Payaguá menaced Spanish travel on the Paraguay river for more than 200 years.[6]

The first European to come into contact with the Payaguá may have been the castaway and explorer Aleixo Garcia. Garcia was killed in 1525 near the Paraguay river, possibly by the Payaguá.[7] In 1527, the explorer Sebastian Cabot fought a river battle against Payaguás near the junction of the Paraguay and Bermejo River in present-day Argentina. The Payaguá force was estimated by a later Spanish chronicler to have numbered 300 canoes (probably an exaggeration as Payaguá canoes typically transported about 10 men). In 1537, the Payaguá killed Juan de Ayolas and 80 Spaniards at a fortress the Spanish had erected, probably near present-day Fuerte Olimpo, Paraguay.[8]

War with the Spanish. The Payaguá were divided into two groups, the northern and the southern. Contact by the Spanish with the southern branch of the Payaguá was divided by Barbara Ganson into two periods: 1528–1730, sporadic, hostile contact; and 1730–1811, extensive contact and accommodation by the Payagua to the Spanish. During the 17th century, the Payaguá, described as "river pirates", menaced the commerce of the yerba mate trade on the Paraguay River, forcing much of the trade to go overland. The Payaguá along with their allies, the Mbayá, also carried out murderous raids to obtain horses, cattle, and other goods from Spanish settlements and Jesuit reductions. The Spanish on their part declared in 1613 a "war of fire and blood" against the Payaguá and Mbayá and sent out numerous expeditions to attempt to kill or enslave them.[9]

War with the Portuguese. The northern branch of the Payaguá was loosely aligned with the Kadiweu people (a band of the Mbayá people). They resisted the Portuguese in Brazil, especially after the discovery of gold near Cuaibá in 1718 initiated a gold rush by Portuguese wealth seekers who mostly arrived by canoe on the Paraguay River.[10] The Payaguá resisted the intrusion by attacking the gold-seekers on the river. Most notably, in 1725 they annihilated a party of 200 men on the river. In 1730, 800 Payaguá warriors killed most of a party of 400. They traded the proceeds of their raids, including gold, to the Spanish in Asunción for iron tools. Reprisals against the Payaguá were ineffective until 1734, when the Portuguese scored a victory, but the next year the Payaguá destroyed a convoy of 50 canoes (perhaps 500 men). Afterwards, the Payaguá attacks continued, but on a lesser scale.[11] The northern bands of the Payagua made peace with the Portuguese in 1752 and in 1766 some of the northerners requested to take up residence near the Jesuit reduction at Belén, Paraguay. However, a few of them continuing raiding until 1789.[12]

Decline. By the early 18th century, the southern Payaguá were being overwhelmed by the Spanish. In 1730, the Spanish changed their policy of "fire and blood" to one of fostering friendly relations and trade with the Payaguá. By the 1740s some of the Payagua were engaged in supplying the Spanish settlers and cities with fish caught in the river. The Payaguá continued to resist adopting Christianity; in 1791 only two among them had become Christians, but a large scale baptism of Payaguá took place in 1792. A 1793 report described the Payaguá as "docile, noble, dedicated to working, subordinated to their superiors, and other good qualities." In the 19th century, the Payaguá became the river police of Paraguay, employed by the government to patrol the rivers and prevent people and goods from entering the country illegally. During the Paraguayan War (1864-1870) the Payaguá were organized by the Paraguayan government into a "Payaguá regiment",[13] and transported wood and other supplies by barge from Asunción to more northerly cities. With their numbers already in decline due to disease, alcoholism, intermarriage, and integration, the war was a demographic disaster for the Payaguá as well as other Paraguayans.[14]

In 1896, the Encyclopaedia Britannica reported that a "subdued remnant" of the Payaguá lived in the Pilcomayo River delta, near Asunción.[15] The last known Payaguá, Maria Dominga Miranda, died in 1942.[16]

Culture

The chronicler Ulrich Schmidl described an encounter with the southern Payaguá in 1536:

"We arrived at a nation called Aigeiss [Payaguá]. They have fish and meat. Both sexes are tall and well-formed. The women are pretty. They paint their bodies and cover their private parts. When we arrived they were in order of battle and ready to fight us on land and water. We fought and killed many of them. They killed 15 of our men. God gives favor to all. These Aigeiss are good fighters, the best of all on water, not so good on land. With time to do so, they had made their women and children flee and had hidden their food and possessions. We could not take or benefit from anything of theirs. Time will tell how this turns out."[17]

See also

References

- ↑ Amigo, Roberto; Escobar, Ticio; Majluf, Natalia (2015). Un viajero virreinal. Acuarelas inéditas de la sociedad rioplatense (in Spanish). Buenos Aires: Hilario. Artes, Letras & Oficios. p. 141. ISBN 9789873392511.

- ↑ Ganson, Barbara (2017), "The Evueví of Paraguay: Adaptive Strategies and Responses to Colonialism", The Americas, Vol 74, Issue 52, p. 466. Downloaded from Project MUSE.

- ↑ Ganson, p. 465

- ↑ Saeger, James Schofield (2008), "Warfare, Reorganization, and Readaptation at the Margins of Spanish Rule--the Chaco and Paraguay," The Cambridge History of the Native Peoples of the Americas, Vol 3, South America, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 263

- ↑ Ganson, p. 468

- ↑ Saegar, James Schofield (2000), The Chaco Mission Frontier: The Guaycuruan Experience, Tucson: University of Arizona Press, pp. 18-19.

- ↑ García Aldonate, Mario (1994). ...Y resultaron humanos: fin de las culturas nativas en territorio argentino. Compañía Literaria, pp. 39, 88.ISBN 9788482130057

- ↑ Gott, Richard (1993), Land Without Evil: Utopian Journeys across the South American WatershedLondon: Verso, p. 81-82. Lest the Payaguá be considered the sole initiator of these conflicts, European expeditions to the Americans routinely demanded food, shelter, women, and porters of native peoples.

- ↑ Ganson, p. 464, 472-478

- ↑ Goodman, Edward Julius (1972), The Explorers of South America, Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, pp.134-136

- ↑ Hemming, John (1978), Red Gold: The Conquest of the Brazilian Indians, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, pp. 395-401

- ↑ Saegar (2008), p. 264; Ganson 481-482.

- ↑ Foote, Nicola, Horst, Harder, D. Rene (2010), "Military Struggle and Identity Formation in Latin America," Gainesville: University Press of Florida, p. 160. Downloaded from Project MUSE.

- ↑ Ganson, pp. 480-486

- ↑ Encyclopaedia Britannica, Vol 2., 1896, p. 62

- ↑ Ganson, p. 486.

- ↑ Cervantes Virtual. Ulrich Schmídel, Viaje al Río de la Plata; notas bibliográficas y biográficas por el teniente general don Bartolomé Mitre; prólogo, traducciones y anotaciones por Samuel Alejandro Lafone Quevedo.