| Polari | |

|---|---|

| Palare, Parlary, Palarie, Palari | |

| Region | United Kingdom |

Native speakers | None[1] |

English-based slang and other Indo-European influences | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | pld |

| Glottolog | pola1249 |

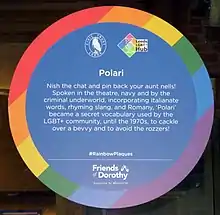

Polari (from Italian parlare 'to talk') is a form of slang or cant used in Britain by some actors, circus and fairground showmen, professional wrestlers, merchant navy sailors, criminals, sex workers, and, particularly, the gay subculture. There is some debate about its origins,[2] but it can be traced to at least the 19th century and possibly as early as the 16th century.[3] There is a long-standing connection with Punch and Judy street puppet performers, who traditionally used Polari to converse.[4]

Terminology

Alternative spellings include Parlare, Parlary, Palare, Palarie and Palari.

Description

Polari is a mixture of Romance (Italian[5] or Mediterranean Lingua Franca), Romani, rhyming slang, sailor slang and thieves' cant. Later it expanded to contain words from Yiddish and 1960s drug subculture slang. It was constantly evolving, with a small core lexicon of about 20 words, including: bona (good[6]), ajax (nearby), eek (face), cod (bad, in the sense of tacky or vile), naff (bad, in the sense of drab or dull, though borrowed into mainstream British English with the sense of the aforementioned cod), lattie (room, house, flat, i.e. room to let), nanti (not, no), omi (man), palone (woman), riah (hair), zhoosh or tjuz (smarten up, stylise), TBH ('to be had', sexually accessible), trade (sex) and vada (see), and over 500 other, lesser-known words.[7] There was once (in London) an East End version, which stressed cockney rhyming slang, and a West End version, which stressed theatrical and classical influences. There was some interchange between the two.[8]

Usage

From the 19th century on, Polari was used in London fishmarkets, the theatre, fairgrounds, and circuses, hence the many borrowings from Romani.[9] As many homosexual men worked in theatrical entertainment, it was also used among the gay subculture at a time when homosexual activity was illegal, to disguise homosexuals from hostile outsiders and undercover policemen. It was also used extensively in the British Merchant Navy, where many gay men joined ocean liners and cruise ships as waiters, stewards, and entertainers.[10]

William Shakespeare used the term bona (good, attractive) in Henry IV, Part 2 (in Act III Scene II), part of the expression bona roba (a lady wearing an attractive outfit).[11] But "there's little written evidence of Polari before the 1890s", according to Peter Gilliver, associate editor of the Oxford English Dictionary. The dictionary's entry for rozzer (policeman), for example, includes this quote from an 1893 book (P. H. Emerson's Signor Lippo – Burnt Cork Artiste):[12] "If the rozzers was to see him in bona clobber they'd take him for a gun" ("If the police were to see him dressed in this fine manner, they would know that he is a thief").[11]

The almost identical Parlyaree has been spoken in fairgrounds since at least the 17th century[13] and is still used by show travellers in England and Scotland. As theatrical booths, circus acts, and menageries were once common parts of European fairs, it is likely that the roots of Polari/Parlyaree lie in the period before both theatre and circus became independent of fairgrounds. The Parlyaree spoken on fairgrounds tends to borrow much more from Romani, as well as other languages and argots spoken by travelling people, such as thieves' cant and backslang.

Henry Mayhew gave a verbatim account of Polari as part of an interview with a Punch and Judy showman in the 1850s. The discussion he recorded references Punch's arrival in England, crediting these early shows to an Italian performer called Porcini (John Payne Collier's account calls him Porchini, a literal rendering of the Italian pronunciation).[14] Mayhew provides the following:

Punch Talk

"Bona Parle" means language; name of patter. "Yeute munjare" – no food. "Yeute lente" – no bed. "Yeute bivare" – no drink. I've "yeute munjare", and "yeute bivare", and, what's worse, "yeute lente". This is better than the costers' talk, because that ain't no slang and all, and this is a broken Italian, and much higher than the costers' lingo. We know what o'clock it is, besides.[4]

There are additional accounts of particular words that relate to puppet performance: "'Slumarys' – figures, frame, scenes, properties. 'Slum' – call, or unknown tongue"[4] ("unknown" is a reference to the "swazzle", a voice modifier used by Punch performers, the structure of which was a longstanding trade secret).

Decline

Polari had begun to fall into disuse in the gay subculture by the late 1960s. The popularity of Julian and Sandy, played by Hugh Paddick and Kenneth Williams (introduced in the radio programme Round the Horne in the 1960s), ensured that some of this secret language became public knowledge.[15] The need for a secret subculture code declined with the partial decriminalisation of adult homosexual acts in England and Wales under the Sexual Offences Act 1967.

Entry into mainstream slang

A number of words from Polari have entered mainstream slang. The list below includes words in general use with the meanings listed: acdc, barney, blag, butch, camp, khazi, cottaging, hoofer, mince, ogle, scarper, slap, strides, tod, [rough] trade.

The Polari word naff, meaning inferior or tacky, has an uncertain etymology. Michael Quinion says it is probably from the 16th-century Italian word gnaffa, meaning "a despicable person".[16] There are a number of false etymologies, many based on backronyms—"Not Available For Fucking", "Normal As Fuck", etc. The phrase "naff off" was used euphemistically in place of "fuck off" along with the intensifier "naffing" in Keith Waterhouse's Billy Liar (1959).[17] Usage of "naff" increased in the 1970s when the television sitcom Porridge employed it as an alternative to expletives, which were not broadcastable at the time.[16] Princess Anne allegedly famously told a reporter, "Why don't you just naff off" at the Badminton horse trials in April 1982,[18] but it has since been claimed that this was a bowdlerised version of what she actually said.[19]

"Zhoosh" (/ˈʒʊʃ/, /ˈʒuːʃ/ or /ˈʒʊʒ/[20]; alternatively spelled "zhuzh," "jeuje," and a number of other variety spellings [21]), meaning to smarten up, style or improve something, became commonplace in the mid-2000s, having been used in the 2003 United States TV series Queer Eye for the Straight Guy and What Not to Wear. "Jush", an alternative spelling of the word, was popularised by drag queen Jasmine Masters after her appearance on the seventh series of RuPaul's Drag Race in 2015.[22][23]

In popular culture

- James Thomson added a glossary of words he thought "obsolete" in his 1825 work The Seasons and Castle of Indolence. He chose to write "Castle of Indolence" "In the manner of Edmund Spenser". Two words he thought needed explaining were "eke", meaning "also", pronounced like Polari's "eek" (face); and "gear or geer", meaning "furniture, equipage, dress". The latter is still used in slang and has thus avoided obsolescence.

- Polari ('Polare') was popularised in the 1960s on the BBC radio show Round the Horne starring Kenneth Horne. Camp Polari-speaking characters Julian and Sandy were played by Hugh Paddick and Kenneth Williams.[24]

- In the Doctor Who serial Carnival of Monsters from 1973, Vorg, a showman, believing the Doctor also to be a showman, attempts to converse with him in Polari. The Doctor says he does not understand him.[25]

- In 1987 the character Ralph Filthy, a theatrical agent played by Nigel Planer in the BBC TV series Filthy Rich & Catflap, regularly used Polari.

- In 1990 Morrissey released the single "Piccadilly Palare" containing a number of lyrics in Polari and exploring a subculture in which Polari was used. "Piccadilly Palare" is also the first song on Morrissey's compilation album Bona Drag, whose title is also taken from Polari.

- In 1990, in Issue #35 of Grant Morrison's run of Doom Patrol, the character Danny the Street is introduced; they speak English heavily flavoured with Polari, with "bona to vada" ("good to see [you]") being their favourite way to greet friends.

- In the 1998 film Velvet Goldmine, two characters speak Polari in a London nightclub. The scene has English subtitles.

- In 2002, two books on Polari were published, Polari: The Lost Language of Gay Men and Fantabulosa: A Dictionary of Polari and Gay Slang, both by Paul Baker.

- In 2015, filmmakers Brian Fairbairn and Karl Eccleston made Putting on the Dish, a short film entirely in Polari.[26]

- The 2016 David Bowie album Blackstar contains a song, "Girl Loves Me", that utilises Polari.[27]

- In 2017, a service at Westcott House, Cambridge (a Church of England theological college) was conducted in Polari; trainee priests held the service to commemorate LGBT History Month; following media attention, Chris Chivers, the Principal, expressed his regret.[28][29][30][31]

- In the 2017 EP Ricky, gay singer Sakima used Polari.[32]

- In 2019, the first opera in Polari, The Sins of the Cities of the Plain (based on the book of the same title), premiered at Espacio Turina in Seville, Spain. The libretto was written in Polari by librettist and playwright Fabrizio Funari and the music is by Germán Alonso. Niño de Elche played the main role. The opera was produced and performed by instrumental ensemble Proyecto OCNOS, formed by Pedro Rojas-Ogáyar and Gustavo A. Domínguez Ojalvo, with the support of ICAS Sevilla, Fundación BBVA and The Librettist.[33]

- The same year, the English-language localisation of the Japanese video game Dragon Quest Builders 2 included a character called Jules, who spoke in Polari with non-standard capitalisation.[34][35]

- Also in 2019, Reaktion Books published Fabulosa!: The Story of Polari, Britain's Secret Gay Language, by Paul Baker.[36][37]

- In the 2020 film Roald & Beatrix: The Tail of the Curious Mouse, a young Roald Dahl, running away from home, meets a man (played by Bill Bailey) who speaks in Polari.

- Richard Milward's 2023 novel Man-Eating Typewriter is written almost entirely in Polari, in the form of fictional memoirs by the character Raymond M. Novak.

Glossary

Numbers:

| Number | Definition | Italian numbers |

|---|---|---|

| medza, medzer | half | mezza |

| una, oney | one | uno |

| dooey | two | due |

| tray | three | tre |

| quarter | four | quattro |

| chinker | five | cinque |

| say | six | sei |

| say oney, setter | seven | sette |

| say dooey, otter | eight | otto |

| say tray, nobber | nine | nove |

| daiture | ten | dieci |

| long dedger, lepta | eleven | undici |

| kenza | twelve | dodici |

| chenter[36] | one hundred | cento |

Some words or phrases that may derive from Polari (this is an incomplete list):

| Word | Definition |

|---|---|

| acdc, bibi | bisexual[38]: 49 |

| ajax | nearby (shortened form of "adjacent to")[38]: 49 |

| alamo! | they're attractive! (via acronym "LMO" meaning "Lick Me Out!)[38]: 52, 59 |

| arva | to have sex (from Italian chiavare, to screw)[39] |

| aunt nell | listen![38]: 52 |

| aunt nells | ears[38]: 45 |

| aunt nelly fakes | earrings[38]: 59, 60 |

| barney | a fight[38]: 164 |

| bat, batts, bates | shoes[38]: 164 |

| bevvy | drink (diminutive of "beverage")[6] |

| bitch | effeminate or passive gay man |

| bijou | small/little (from French, jewel)[38]: 57 |

| bitaine | whore (French putain) |

| blag | pick up[38]: 46 |

| bold | homosexual[39] |

| bona | good[38]: 26, 32, 85 |

| bona nochy | goodnight (from Italian – buona notte)[38]: 52 |

| butch | masculine; masculine lesbian[38]: 167 |

| buvare | a drink; something drinkable (from Italian – bere or old-fashioned Italian – bevere or Lingua Franca bevire)[38]: 167 |

| cackle | talk/gossip[38]: 168 |

| camp | effeminate (possibly from Italian campare "exaggerate, make stand out") (possibly from the phrase 'camp follower' those itinerants who followed behind the men in uniform/highly decorative dress) |

| capello, capella, capelli, kapella | hat (from Italian – cappello)[38]: 168 |

| carsey, karsey, khazi | toilet[38]: 168 |

| cartes | penis (from Italian – cazzo)[38]: 97 |

| cats | trousers[38]: 168 |

| charper | to search or to look (from Italian acchiappare, to catch)[38]: 168 |

| charpering omi | policeman |

| charver | sexual intercourse[38]: 46 |

| chicken | young man |

| clevie | vagina[40] |

| clobber | clothes[38]: 138, 139, 169 |

| cod | bad[38]: 169 |

| corybungus | backside, posterior[40] |

| cottage | a public lavatory used for sexual encounters (public lavatories in British parks and elsewhere were often built in the style of a Tudor cottage) |

| cottaging | seeking or obtaining sexual encounters in public lavatories |

| cove | taxi[38]: 61 |

| dhobi / dhobie / dohbie | wash (from Hindi, dohb)[38]: 171 |

| Dilly boy | a male prostitute, from Piccadilly boy |

| Dilly, the | Piccadilly, a place where trolling went on |

| dinari | money (Latin denarii was the 'd' of the pre decimal penny)[41] |

| dish | buttocks[38]: 45 |

| dolly | pretty, nice, pleasant, (from Irish dóighiúil/Scottish Gaelic dòigheil, handsome, pronounced 'doil') |

| dona | woman (perhaps from Italian donna or Lingua Franca dona)[38]: 26 |

| ecaf | face (backslang)[38]: 58, 210 |

| eek/eke[36] | face (abbreviation of ecaf)[38]: 58, 210 |

| ends | hair[6] |

| esong, sedon | nose (backslang)[38]: 31 |

| fambles | hands[40] |

| fantabulosa | fabulous/wonderful |

| farting crackers | trousers[40] |

| feele / feely / filly | child/young (from the Italian figlio, for son) |

| feele omi / feely omi | young man |

| flowery | lodgings, accommodations[40] |

| fogus | tobacco |

| fortuni | gorgeous, beautiful[40] |

| fruit | gay man |

| funt | pound £ (Yiddish) |

| fungus | old man/beard[40] |

| gelt | money (Yiddish) |

| handbag | money |

| hoofer | dancer |

| HP (homy palone) | effeminate gay man |

| irish | wig (from rhyming slang, "Irish jig") |

| jarry | food, also mangarie (from Italian mangiare or Lingua Franca mangiaria) |

| jubes | breasts |

| kaffies | trousers |

| lacoddy, lucoddy | body |

| lallies / lylies | legs, sometimes also knees (as in "get down on yer lallies") |

| lallie tappers | feet |

| latty / lattie | room, house or flat |

| lau | lay or place upon[42] |

| lavs | words[43] (Gaelic: labhairt to speak) |

| lills | hands |

| lilly | police (Lilly Law) |

| lyles | legs (prob. from "Lisle stockings") |

| luppers | fingers (from Yiddish lapa – paw) |

| mangarie | food, also jarry (from Italian mangiare or Lingua Franca mangiaria) |

| manky | worthless, dirty (from Italian mancare – "to be lacking")[44] |

| martinis | hands |

| measures | money |

| medza/medzer | half (from Italian mezzo) |

| medzered | divided[45] |

| meese | plain, ugly (from Yiddish mieskeit, in turn from Hebrew מָאוּס repulsive, loathsome, despicable, abominable) |

| meshigener | nutty, crazy, mental (from Yiddish 'meshugge', in turn from Hebrew מְשֻׁגָּע crazy) |

| meshigener carsey | church[43] |

| metzas | money (from Italian mezzi, "means, wherewithal") |

| mince | walk affectedly |

| mollying | involved in the act of sex[46] |

| mogue | deceive |

| munge | darkness |

| naff | awful, dull, hetero |

| nana | evil |

| nanti | not, no, none (from Italian, niente) |

| national handbag | dole, welfare, government financial assistance |

| nishta | nothing[6] from yiddish nishto נישטא meaning nothing |

| ogle | look admiringly |

| ogles | eyes |

| oglefakes | glasses |

| omi | man (from Romance) |

| omi-palone | effeminate man, or homosexual |

| onk | nose (cf "conk") |

| orbs | eyes |

| orderly daughters | police |

| oven | mouth (nanti pots in the oven = no teeth in the mouth) |

| palare / polari pipe | telephone ("talk pipe") |

| palliass | back |

| park, parker | give |

| plate | feet (Cockney rhyming slang "plates of meat"); to fellate |

| palone | woman (Italian paglione – "straw mattress"; cf. old Cant hay-bag – "woman"); also spelled "polony" in Graham Greene's 1938 novel Brighton Rock |

| palone-omi | lesbian |

| pots | teeth |

| quongs | testicles |

| reef | touch |

| remould | sex change |

| rozzer | policeman[11] |

| riah / riha | hair (backslang) |

| riah zhoosher | hairdresser |

| rough trade | a working class or blue collar sex partner or potential sex partner; a tough, thuggish or potentially violent sex partner |

| scarper | to run off (from Italian scappare, to escape or run away or from rhyming slang Scapa Flow, to go) |

| scharda | shame (from German schade, "a shame" or "a pity") |

| schlumph | drink |

| schmutter | apparel[47] from yiddish shmatte שמאטע meaning rag |

| schooner | bottle |

| scotch | leg (scotch egg=leg) |

| screech | mouth, speak |

| screeve | write[47] (either from Irish scríobh/Scottish Gaelic sgrìobh, Scots scrieve to write or italian 'scrivere' meaning to write) |

| sharpy | policeman (from – charpering omi) |

| sharpy polone | policewoman |

| shush | steal (from client) |

| shush bag | hold-all |

| shyker / shyckle | wig (mutation of the Yiddish sheitel) |

| slap | makeup |

| so | homosexual (e.g. "Is he 'so'?") |

| stimps | legs |

| stimpcovers | stockings, hosiery |

| strides | trousers |

| strillers | piano |

| switch | wig |

| TBH (to be had) | prospective sexual conquest |

| thews | thighs |

| tober | road (a Shelta word, Irish bóthar); temporary site for a circus, carnival |

| todd (Sloan) or tod | alone |

| tootsie trade | sex between two passive homosexuals (as in: 'I don't do tootsie trade') |

| trade | sex, sex-partner, potential sex-partner |

| troll | to walk about (esp. looking for trade) |

| vada / varder | to see (from Italian dialect vardare = guardare – look at)

vardered – vardering |

| vera (lynn) | gin |

| vogue | cigarette (from Lingua Franca fogus – "fire, smoke") |

| vogueress | female smoker |

| wallop | dance[48] |

| willets | breasts |

| yeute | no, none |

| yews | (from French "yeux") eyes |

| zhoosh | style hair, tart up, mince (cf. Romani zhouzho – "clean, neat") zhoosh our riah – style our hair |

| zhooshy | showy |

Usage examples

Omies and palones of the jury, vada well at the eek of the poor ome who stands before you, his lallies trembling. – taken from "Bona Law", one of the Julian and Sandy sketches from Round The Horne, written by Barry Took and Marty Feldman

- Translation: "Men and women of the jury, look well at the face of the poor man who stands before you, his legs trembling."

So bona to vada...oh you! Your lovely eek and your lovely riah. – taken from "Piccadilly Palare", a song by Morrissey

- Translation: "So good to see...oh you! Your lovely face and your lovely hair."

As feely ommes...we would zhoosh our riah, powder our eeks, climb into our bona new drag, don our batts and troll off to some bona bijou bar. In the bar we would stand around with our sisters, vada the bona cartes on the butch omme ajax who, if we fluttered our ogle riahs at him sweetly, might just troll over to offer a light for the unlit vogue clenched between our teeth. – taken from Parallel Lives, the memoirs of renowned gay journalist Peter Burton

- Translation: "As young men...we would style our hair, powder our faces, climb into our great new clothes, don our shoes and wander/walk off to some great little bar. In the bar we would stand around with our gay companions, look at the great genitals on the butch man nearby who, if we fluttered our eyelashes at him sweetly, might just wander/walk over to offer a light for the unlit cigarette clenched between our teeth."

In the Are You Being Served? episode "The Old Order Changes", Captain Peacock asks Mr Humphries to get "some strides for the omi with the naff riah" (i.e., trousers for the fellow with the unstylish hair).[49]

See also

- African-American Vernacular English (sometimes called Ebonics)

- Bahasa Binan

- Boontling

- Caló (Chicano)

- Carny, North American fairground cant

- Gayle language

- Gay slang

- Grypsera

- IsiNgqumo

- Lavender linguistics

- Lunfardo and Vesre

- Mediterranean Lingua Franca

- Pajubá

- Julian and Sandy

- Rotwelsch

- Shelta

- Swardspeak, argot used by LGBT people in the Philippines

- Verlan

- Lubunca

References

- ↑ Polari at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ↑ Quinion, Michael (1996). "How bona to vada your eek!". WorldWideWords. Archived from the original on 7 September 2019. Retrieved 20 February 2006.

- ↑ Collins English Dictionary, Third Edition

- 1 2 3 Mayhew, Henry (1968). London Labour and the London Poor, 1861. Vol. 3. New York: Dover Press. p. 47.

- ↑ "British Spies: Licensed to be Gay." Time. 19 August 2008. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 "The secret language of polari – Merseyside Maritime Museum, Liverpool museums". Liverpoolmuseums.org.uk. Retrieved 5 July 2018.

- ↑ Baker, Paul (2002) Fantabulosa: A Dictionary of Polari and Gay Slang. London: Continuum ISBN 0-8264-5961-7

- ↑ David McKenna, A Storm in a Teacup, Channel 4 Television, 1993.

- ↑ Jivani, Alkarim (January 1997). It's not unusual : a history of lesbian and gay Britain in the twentieth century. Bloomington. ISBN 0253333482. OCLC 37115577.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ "Gay men in the Merchant Marine". Liverpool Maritime Museum. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- 1 2 3 Beverley D'Silva (10 December 2000). "Mind your language". The Observer. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- ↑ "Historical Origins of English Words and Phrases". Live Journal. 24 October 2008. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- ↑ Partridge, Eric (1937) Dictionary of Slang and Unconventional English

- ↑ Punch and Judy. John Payne Collier; with Illustrations by George Cruikshank. London: Thomas Hailes Lacey, 1859.

- ↑ Richardson, Colin (17 January 2005). "Colin Richardson: Polari, the gay slang, is being revived". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 July 2018.

- 1 2 Quinion, Michael. "Naff". World Wide Words. Retrieved 10 January 2010.

- ↑ Waterhouse, Keith (1959). Billy Liar. Michael Joseph. pp. 35, 46. ISBN 0-7181-1155-9. p35 "Naff off, Stamp, for Christ sake!" p46 "Well which one of them's got the naffing engagement ring?"

- ↑ The New Partridge Dictionary of Slang and Unconventional English Dalzell and Victor (eds.) Routledge, 2006, Vol. II p. 1349.

- ↑ Llewelyn, Abbie (8 September 2019). "Princess never said 'naff off' -- 'We made it up'". Daily Express. London. Retrieved 28 January 2022.

- ↑ "Definition for zhoosh – Oxford Dictionaries Online (World English)". Oxforddictionaries.com. Archived from the original on 11 September 2017. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- ↑ Phelan, Hayley (31 January 2022). "'Jeuje,' 'Zhoosh,' 'Zhuzh': A Word of Many Spellings, and Meanings". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 12 January 2024. Retrieved 12 January 2024.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 13 October 2023 suggested (help) - ↑ "Jasmine Masters the meaning of jush". Retrieved 26 November 2022 – via YouTube.

- ↑ Schiller, Rebecca (4 June 2018). "'Drag Race' Queen Jasmine Masters Explains What 'Jush' Means: Watch". Billboard. Retrieved 26 November 2022.

- ↑ Stevens, Christopher (2010). Born Brilliant: The Life of Kenneth Williams. John Murray. p. 206. ISBN 978-1-84854-195-5.

- ↑ Baker 2003, p. 161.

- ↑ J. Bryan Lowder (28 July 2015). "Polari, the gay dialect, can be heard in this great short film "Putting on the Dish". Slate. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- ↑ Eastmond, Dean. "Remembering Polari, the Forgotten Language of Britain's Gay Community". Vice. Vice Media.

- ↑ "Church 'regret' as trainees hold service in gay slang". BBC News. 4 February 2017. Retrieved 4 February 2017.

- ↑ Sherwood, Harriet (3 February 2017). "C of E college apologises for students' attempt to 'queer evening prayer'". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077.

- ↑ Flood, Rebecca (4 February 2017). "Church expresses 'huge regret' after Cambridge LGBT commemoration service held in gay slang language". The Independent. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- ↑ Robb, Simon (4 February 2017). "Priests delivered a service in gay slang and the church weren't happy". Metro. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- ↑ Crowley, Patrick (9 October 2017). "Sakima's Dirty Pop: Meet Music's New Queer Voice". Billboard. Retrieved 7 October 2018.

- ↑ Sevilla, Diario de (26 May 2019). "Pornografía bruitista". Diario de Sevilla (in European Spanish). Retrieved 26 June 2019.

- ↑ Square Enix (20 December 2018). Dragon Quest Builders 2 (Nintendo Switch). Square Enix.

- ↑ Hawkes, Edward. "The Coded Gay Jargon in Dragon Quest Builders 2".

- 1 2 3 Baker, Paul (2019). Fabulosa!: The Story of Polari, Britain's Secret Gay Language. London: Reaktion Books. ISBN 9781789142945.

- ↑ "Fabulosa! by Paul Baker from Reaktion Books". reaktionbooks.co.uk. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 Baker 2003.

- 1 2 "What is Polari All About?". Polari Magazine. 13 August 2012. Retrieved 30 July 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Grose, Francis (2012). 1811 Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue. tebbo. ISBN 978-1-4861-4841-7

- ↑ C. H. V. Sutherland, English Coinage 600-1900 (1973, ISBN 0-7134-0731-X), p. 10

- ↑ "A Polari Christmas". Polari Magazine. 12 December 2009. Retrieved 30 July 2018.

- 1 2 "The Polari Bible". .josephrichardson.tv. Retrieved 30 July 2018.

- ↑ "Manky". Collins English Dictionary. Retrieved 21 December 2018.

- ↑ "Let There Be Sparkle". Polari Magazine. 10 December 2012. Retrieved 30 July 2018.

- ↑ D'Silva, Beverley (10 December 2000). "The way we live now: Mind your language". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 July 2018.

- 1 2 "Polari Bible". josephrichardson.tv/home.html. Retrieved 1 August 2018.

- ↑ "World Wide Words: How bona to vada your eek!". World Wide Words. Archived from the original on 7 September 2019. Retrieved 5 July 2018.

- ↑ "The Old Order Changes". Are You Being Served?. 18 March 1977.

Bibliography

- Baker, Paul (2002). Fantabulosa: A Dictionary of Polari and Gay Slang. London: Continuum. ISBN 0-8264-5961-7.

- Baker, Paul (2003). Polari: The Lost Language of Gay Men. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-50635-4.

- Elmes, Simon; Rosen, Michael (2002). Word of Mouth. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-866263-7.

External links

- Web based dictionary on Polari compiled by Australian writer Javant Biarujia

- Chris Denning's article on Polari with bibliography

- The Polari Bible compiled by The Manchester Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence

- Polari Mission exhibit (archived) at the University of Manchester's John Rylands Library

- Colin Richardson, The Guardian, 17 January 2005, "What brings you trolling back, then?"

- Liverpool Museums: The secret language of polari (archived)

- Paul Clevett's Polari Translator

- Putting it on the Dish, a 2015 short film featuring Polari extensively

- A brief history of Polari: the curious after-life of the dead language for gay men, 8 February 2017.