| Peking-Mukden Railway PMR | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Overview | |

| Native name | 京奉铁路 |

| Status | Predecessor of current Beijing-Tianjin section of Beijing–Shanghai railway, Tianjin–Shanhaiguan railway, Shenyang–Shanhaiguan Railway and Qidaoqiao-Luanxian Branchline |

| Locale | Beijing, Tianjin, northeast of hebei, and southwest of liaoning |

| Service | |

| Type | trunkline |

| History | |

| Opened | 31 July 1897 |

| Other names | Beijing-Liaoning Railway (北宁铁路), Beiping-Mukden Railway (平奉铁路), Trans-Pass Railway (关内外铁路) |

| Closed | 7 January 1932 |

| Technical | |

| Line length | 840km |

| Number of tracks | Double-track in some sections |

| Track gauge | Standard-gauge railway |

Peking–Mukden Railway (Chinese: 北京-奉天铁路; pinyin: Běijīng – Fèngtiān Tiělù) was a 19th-century steam powered trunkline connecting Peking (Beijing) and Mukden (former name of Shenyang) through Tianjin, northeastern Hebei, and southwestern Liaoning; it was a crucial railway in North China and Northeast China.

The history of the railway can date back to Kaiping Tramway (often known as Tangshan–Xugezhuang Railway in Chinese) completed in 1881, which became PMR after several extensions in the next 31 years. It was significant and influential in the Railway development and even transportation histories in China since it was the first trunk line being built and operated successfully. Although Woosung Road and had been built years before PMR, they were neither built for practical use nor in operation for more than a year.

Timeline

The timeline of how Kaiping Tramway was transformed into the trunkline PMR was shown below.

| Time | Incidents or changes |

|---|---|

| 1880 | The idea of Kaiping Tramway was proposed for the first time |

| May 1881 | The construction of Kaiping Tramway started |

| November 1881 | The construction of Kaiping Tramway completed |

| Feb 1887 | The administrative of Imperial Chinese Navy proposed a railway from to Shanhai Pass |

| August 1887 | Kaiping Tramway was extended to Lutai

and renamed Tangshan–Lutai Railway |

| August 1888 | Tangshan–Lutai Railway was extended to Dagu

and renamed Tangshan–Tianjin Railway |

| 1888 | Tianjin–Tongzhou Railway was first proposed |

| 1889 | Implementation of the Tianjin–Tongzhou Railway plan was halted |

| 1890 | Tangshan–Tianjin Railway was extended to Guye

and renamed as Guye–Tianjin Railway |

| 1891 | Kwantung Railway Plan was approved |

| 1894 | Guye-Tianjin railway was extended to Shanhai Pass

and renamed as Tianjin–Yu Pass Railway (aka. Imperial Railway of North China) |

| Tianjin-Yu Pass Railway was extended to Suizhong County | |

| 1895 | The construction of Tianjin–Lugou Bridge railway started |

| 1897 | Tianjin–Lugou Bridge railway was built to Fengtai District |

| August 1897 | Tianjin-Lugou Bridge Railway and Tianjin–Yu Pass Railway

was combined as Trans-(Shanhai)Pass Railway |

| June 1900 | The railway was extended to Dahushan and yingkou |

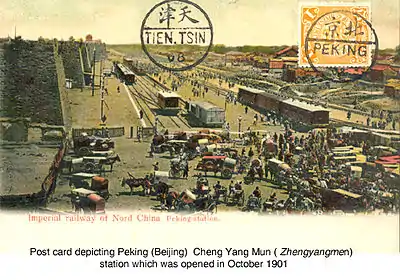

| 1901 | The railway was extended from Fengtai to zhengyangmen in Beijing |

| 1904 | The railway was extended to Xinmin, Liaoning |

| April 1907 | Chinese government bought the ownership of Japanese-built Xinmin–Mukden railway

and changed it to standard gauge |

| 1907 | The railway from Beijing to Fengtian was renamed as Peking–Mukden railway |

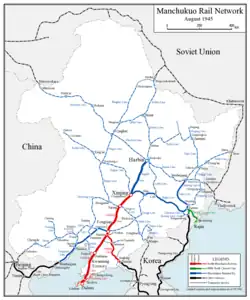

| January 1932 | The section east of the Shanhai Pass was seized by SMR and renamed Mukden–Shanhaiguan railway

while the rest of the railway was renamed as Beijing–Shanhaiguan railway |

The Inner-Pass section

Predecessor – Kaiping Tramway

Kaiping tramway, commonly known as Tangshan–Xugezhuang railway in China, was the first railway built for transportation purpose[note 1] and was regarded as the origin of China's railway development.[1] With the length of about 9 km, this railway was completed in November 1881 as a tramway to help the coals in Kaiping Mines move to Tangshan to meet the demands of Imperial Chinese Navy and China Merchants Steam Navigation Company. As the supply of Kaiping Mines increased, this tramway was extended to lutai and renamed Tangshan–Lutai Railway in 1887.[2]

Conversion to trunk line

On 5 March 1887, The Administrative of Imperial Chinese Navy[note 2] reported to the royal court, requesting for railway's further extension to Taku[note 3] in the west and Shanhai Pass in the east, to make troops move faster.[2] Claude W. Kinder was called upon to survey the route. Li had to overcome opposition in the Imperial Court....[3] but gained sanction for the line to be extended 50 miles to Tianjin. Kinder, as Chief Engineer of the now newly named China Railway Company, was then permitted to secure the services of several more foreign engineers which included Resident Engineers A.W.H. Bellingham and W. Watson.

The railway was extended from Lutai to Taku in March 1888,[4] and to Tianjin in August.[5] Having been built for 14 months, the railway was completed and renamed as Tangshan-Tianjin Railway.[5] Limited train services commenced in August 1888.[3][6][7] On 9 October, the opening ceremony of Tangshan-Tianjin Railway, presented by Zhili Governor Zhou Fu, was held in Tianjin.[2] After examining the quality of the equipments in person, Li Hongzhang said that "the railway from Tianjin to Tangshan is steady, and the bridges and stations are all built in compliances with technical requirements".[8] At this point, the length of this railway was extended to 130km.[9] The cost of the construction of the extension to Tianjin was 12.4 thousand silver Tael per km and 1.5 million silver Tael in total.

Imperial Court opposed the western extension while sanctioned the northern extension. Under the permission and the demand of transportation from the new-built colliery at Linxi, Guye, the railway reached Guye in late 1890, Lanchou[note 4] in 1892, and Shanhaiguan in 1894,[10] during which period the line was transferred to the control of a newly formed Imperial Chinese Railway Administration (Chinese: 北洋官铁路局).[3]

It was during this period of expansion that Jeme Tien Yow joined the railway company in 1888 as a cadet engineer under Kinder's supervision. Kinder highly appreciated the talents of this Yale-graduated engineer and Jeme was soon promoted first to Resident and then District Engineer. In all Jeme spent 12 years working on various sections of this railway.[11]

Predecessor – Tientsin–Lugou Bridge Railway

Tientsin-Lugou Bridge Railway was built from 1895 to 1897 as a mark of reform in the Royal Court. With the length of 150km, this railway connected Beijing, langfang (in hebei), and tianjin.

Extension

In 1901, the extension line was built to connect Ma Chiu Pu to Zhengyangmen. When it was completed, the section in Beijing extended along the border between occupation zones controlled by British and German; specifically, the line extended eastward to Yung Ting Men and the Temple of Heaven, turned northward to Dong Bian Men, and turned westward to Zhengyangmen.[9]

Beijing under the capture of Eight-Nation Alliance. The yellow section, mainly at the lower-right corner, was the British-controlled zones.

Beijing under the capture of Eight-Nation Alliance. The yellow section, mainly at the lower-right corner, was the British-controlled zones. water tower and demolished wall near Yong Ding Men

water tower and demolished wall near Yong Ding Men Station at the Temple of Heaven

Station at the Temple of Heaven new-built Zheng Yang Men station in 1900

new-built Zheng Yang Men station in 1900

The construction of the outer-pass section

Planning

At the beginning of 1890, Zongli Yamen suggested railway construction in Northeast China to resist Japan's lust on Korean Peninsula.[2] In April, Hong Jun, the Envoy to Russian Empire, reported Russian's plan of Trans-Siberian Railway, making the Royal Court shocked.[9] To eliminate the potential territorial threats, the Royal Court suspended the construction of Beijing–Hankou railway and ordered Li Hongzhang to "prepare well" the Kwantung[note 5] Railway from Yingkou to Jilin City and Hunchun.[2] Then, Li sent 2 engineers, Kinder and Cox, to examine the landform. When they came back in November, Li told Navy Administrative that the railway proposed faced huge difficulties in construction and potential low revenue because of the sparse population; moreover, this plan might create tension in Sino-Russian relations. Instead, Li proposed another route from Guye to Shengjing and Jilin City,[9] which was approved in early 1891.[2] When the second land surveying team came back, the details of the route were confirmed as from Shanhai Pass to Jinzhou, Xinmin, Shengjing, and Jilin.[9] In March 1891, Li Hongzhang reported the details of Kwantung Railway, including the methods of construction and the modification on the route, to the Royal Courts; besides, he requested the funds for Beijing-Hankou Railway – 2 million Silver Teal annually – for the construction of Kwantung Railway.[2] The plan was approved on 13 March and Official Railway Bureau of Imperial North China[note 6] was founded afterward.[2] This was the first time the government preside railway construction.[2]

Construction

Plans to continue the railway North-eastwards beyond Shan Hai Kuan (Shanhaiguan) to Jinzhou, Shenyang and Jilin were set back by the lack of funds and because of First Sino-Japanese War (August 1894 to March 1895). By 1896 the rails had only reached Chung Ho So (pinyin: Zhonghousuo 中后所, nowadays Suizhong County), 40 miles beyond Shan Hai Kuan.[10] China's loss of the war with Japan brought about Li Hung Chang's disgrace and virtual removal from power, and with this came new management. After a short power struggle between rival factions, Sheng Hsuan Huai succeeded in gaining control of this new organization and appointed his own supporters to the directorate. Among them, the most prominent was (Chinese: 胡燏棻; pinyin: Hu Yufen), who was appointed Director-General and made responsible for all sections of the Railway.[3][12][13]

During the period 1898-9 a British loan of £2,300,000 was negotiated and an issue of bonds raised in London for the purpose of extending this line northwards to Xinmin and a branch line from Koupangtzu[note 7] to Yingkou. The loan was arranged by the British and Chinese Corporation, a joint venture and front for the Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation and Jardine Matheson and Company. In spite of objections from the Russians (who were themselves busy grabbing control of Chinese territory in Manchuria) the line to Chinchou was eventually completed in 1899.[14]

On 31 July 1897, the bureaus of Tientsin-Lugou Bridge Railway and Tientsin-Yu Pass Railway merged and formed new Trans-Pass Railway.

Under the control of foreign power, a small port was developed at Qinhuangdao with a six-mile branch line joining the mainline a few miles southwest of Shan Hai Kuan at Tangho.[note 8]

In April 1902, the Russian Empire signed the Treaty of Recession(Chinese:交收东三省条约); afterward, the Russian government agreed to recall troops in 3 phases[note 9] and returned the outer-Pass (Shanhai Pass-Yingkou-Dahushan) section. In exchange, the Qing Royal Court agreed to consult Russia about the construction of railways in the south part of Northeast China.[15] However, the Russian government broke their words and only receded to the east bank of Liao River; moreover, they showed their disagreement with the construction of Liao River Bridge by citing the Convention for the Lease of the Liaotung Peninsula[note 10].[9] Under this situation, the outer-pass section can only be extended 89 km to Xinmin in 1904; thence, the length of this railway reached 773 km.[9]

Xinmin Tramway issue

The Russian troops' refusal of withdrawal intensified the rivalry between Japan and Russia and caused the Russo-Japanese War. Weak in military forces, the Chinese government had no choice but to announce the region east of Liao River as "Battlefield" and "Neutrality". However, the Japanese forces went beyond the line by quartering in Xinmin (located west of Liao River) and built the narrow-gauge (2 ft to 3.5 ft) tramway from Xinmin to Huanggutun railway station, aka. Xinmin–Fengtian Tramway. The protests from Chinese officials, though for several times[note 11], were ignored.[9]

| Period | Section | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| May 1904 | Xinmin–Gaolitun[note 12] | Japanese troops built this section.

Since this section was in a neutral region, troops had to camouflage during construction. When completed, supplies can be disembarked at Yingkou Port and transported to Xinmin through Liao River. |

| March–April 1905 | Gaolitun–Mukden | This section was built.

The engine of this section was Handcar, and the track gauge was 2 ft/600 mm. |

| June 1905 | Mukden Station–Little West Gate | This section was built. |

| December 1905 | Xinmin–Mukden | The gauge of this section was converted to 3 ft 6 in,

and the engine was changed to Steam locomotive. A newly built bridge on Liao River replaced the ferry in Gaolitun. |

| August 1906 | Xinmin–Mukden | Routine services, including passengers and cargos trains, started to operate for residents nearby. |

In 1907 this extension was purchased by Imperial Railways of North China at a price of 1.66 million Japanese yen and the agreement that the railway from Jilin to Changchun should be funded by Japanese. The conversion to Standard-gauge railway was finished in the same year,[22]: 574–575 and the construction of Liao River Bridge was finished in 1908.[9]

Reaching Mukden downtown

When the war ended, the Treaty of Portsmouth was signed and the South Manchuria branch of the Chinese Eastern Railway was transferred to Japan's control and renamed as South Manchuria Railway. To extend further, the Trans-Pass Railway had to pass by the surrounding areas of SMR. After years of negotiation, the Chinese and Japanese governments signed the Agreement of Peking-Mukden Railway extension, in which China allowed Japan to build the branch line from Dashiqiao to Yingkou, and Japan, in exchange, allowed PMR to go under SMR near Huanggutun railway station and reach the downtown of Mukden.[9] This extension was completed on 20 December 1911, and a new Mukden Station opened near Xiaoximen,[9] which was renovated by Yang Tingbao to the biggest station in the city – Shenyang North railway station in 1927[23]

Destructions brought by wars

The Boxer uprising of 1900 brought a complete halt to railway construction progress and total destruction of large sections of the existing railway in around Peking and Tientsin. The railway's appointed new Managing-Director, Hsu Ching Cheng (pinyin: Xu Jingcheng 許景澄), was executed for being "too pro-foreign".[24] Moreover, Fengtai and Majiapu Station were destructed by boxers. During the invasion of the Eight-Nation Alliance, Russian troops sieged the section from Tianjin railway station to Yangcun railway station, while the British troops were trying to take over this section.[2] During the resistance, the Chinese army and Boxers attacked Tianjin Station rigorously and dismantled the section from Tanggu to Beijing.[2] On 17 January 1901, after negotiations, the Russian troops receded to the east of the Pass and took away equipment, including machines and rolling stocks, from the railway and affiliated factories on their way. On 7 September, after the Boxer Protocol was signed, the foreign states involved were approved to quarter near the railway and stations. In August 1902, the Chinese government reclaimed administrative power from British and Russian troops. However, before the reclamation, the Chinese government signed, with the British government, the Agreements after the Handover of Trans-Pass, which yielded the administrative power de facto to the British.[9]

Tientsin railway station with German military officers at 1900

Tientsin railway station with German military officers at 1900 Beijing under the capture of Eight-Nation Alliance. The yellow section, mainly at the lower-right corner, was the British-controlled zone, while the red one was controlled by German troops.

Beijing under the capture of Eight-Nation Alliance. The yellow section, mainly at the lower-right corner, was the British-controlled zone, while the red one was controlled by German troops. The remnant of Majiapu Station

The remnant of Majiapu Station The destructed Fengtai locomotive depot and compartments inside

The destructed Fengtai locomotive depot and compartments inside

On 4 January 1912, days after the outbreak of Xinhai Revolution, the uprising forces were going to the west of the Shanhai Pass by train and hit hard in Luanzhou by Cao Kun, Wang Huaiqing, and their reinforcements from Shijiazhuang[25]

On 4 June 1928, Zhang Zuolin, the last leader of Beiyang government, en route back to Mukden, was assassinated near Huanggutun Station by dynamites planted by Kwantung Army.

Split

After Mukden Incident, on 7 January 1932, supported by Imperial Japanese Army, Manchukuo sieged the outer-Pass section, transferred to SMR's control, and renamed it as Mukden-Shanhaiguan Railway, while the inner-Pass section was renamed as Beijing–Shanhaiguan railway and controlled afterwards.[26][27] After the Marco Polo Bridge Incident, the Beijing–Shanhaiguan railway was taken control by North China Transportation Company[28]

Operation

Administration

Following the relief of the besieged foreign legations in Peking by an international allied expeditionary force, the Chinese government lost control of what remained of the badly damaged railway system for a two-year period of allied foreign occupation. British and other foreign military units repaired the line between Tientsin and Peking (1900–1902) and the railway was also extended from the Ma Chiu Pu terminus to new Peking stations. What was built first was the tramway from Ma Chiu Pu to Yong Ding Men by the British in December 1900.[29] For two years (1900–1902) the inner-pass section of this railway was under the overall command of a British army "Royal Engineers" contingent using the name "British Railway Administration" (BRA) while the outer-pass section (from Shanhai Pass to Xinmin) was controlled by Russians until returned to China on 29 September 1902. During the BRA period, the railway operated a traveling post office train and a special overprinted Chinese postal stamp was introduced for mailing letters carried by the BRA's express mail trains.[30]

After civilian control of the railway was resumed in late 1902, Claude Kinder was reinstated as Chief Engineer and also given additional and more powerful responsibilities as general manager. Strongman Yuan Shikai had himself appointed as Director-General of Railways and Kinder's former boss, Hu Yu-fen, who had been ousted in 1899, came back to power as the Assistant Director-General. The Chinese railway administration also had the services of a bright Western-educated new Secretary, returned Chinese Educational Mission student Liang Ju Hao (pinyin: Liang Ruhao 梁汝浩), better known to Europeans as M.T. Liang.[31]

Accidents

- On 25 March 1889, there was a head-on collision between two trains at Chung Liang Cheng (Junliangcheng, simplified Chinese: 军粮城; traditional Chinese: 軍糧城). English train driver, M. Jarvis, had waited a long time in the station passing loop and impatiently entered the next section of single track before the arrival of an oncoming train. As a result of the collision, four carriages caught fire and several injured people were burned alive. Driver Dawson survived but the offending driver, Jarvis, one fireman and seven passengers died in the crash, while more died several days later from their burns and injuries. It was alleged by junior staff that Jarvis had been drinking heavily before the crash.[32][note 13][33]

Notes

- ↑ rather than for exploration like Woosung Road, which was dismantled in 1877

- ↑ The Administrative of Imperial Chinese Navy, founded in 1885, was in charge of the constructions and operations of railways.[2]

- ↑ The railway station was actually located on the opposite side of the river at Tanggu

- ↑ simplified Chinese: 滦州; traditional Chinese: 灤州; pinyin: luan zhou

- ↑ Kwantung means "East of the Pass", a word to describe Manchuria; here the "Pass" refers to the famous Shanhai Pass.

- ↑ Chinese:北洋官铁路局, pinyin:bei yang guan tie lu ju

- ↑ simplified Chinese: 沟帮子; traditional Chinese: 溝幫子

- ↑ simplified Chinese: 汤河; traditional Chinese: 湯河; pinyin: Tanghe

- ↑ Phase 1: Recede from the west side of Liao River 6 months after the signature of the Treaty;

Phase 2: Recede from Shengjing and Jilin Province 6 months later;

Phase 3: Recede from Heilongjiang 6 months later. - ↑ The Convention mentions that China shall not "yield the rights of railway construction in the region of South Manchuria Branch of Chinese Eastern Railway to other states", while the construction of Trans-Pass Railway was presided and funded by British.

- ↑ Zeng Wen, the mayor of Xinmin objected that Japan's quartering violated the principle of neutrality ,[16] and the Foreign Affair Ministry opposed as well by claiming that "Xinmin, a city out of the battlefield, is not suitable for railway construction. The officials from your country(Japan) shall not build any tramway to ensure the neutrality."[17]。

- ↑ a ferry at the east side of Liao River

- ↑ The locomotives at this time were driven by mainly English drivers and a few local Chinese, all under the charge of Locomotive Superintendent G.D. Churchwood. The Traffic Department was headed by Manager R.W. Lemmon with two English Head-Guards with a staff of local officers.The hapless junior Chinese stationmaster, who had attempted to restrain the errant British driver, was partially blamed for this crash and disciplined. In an obvious case of racialist bias, the English press in Shanghai blamed the railway company "for making unjustified economies" and "failing to employ enough foreign guards and supervisors". They overlooked the obvious i.e. had all the drivers then been Chinese and not foreign drivers, the chances of enforcing discipline on the driver would have been that much easier.

References

- ↑ "从中国铁路源头出发". 人民铁道. 24 January 2019. Archived from the original on 29 March 2019. Retrieved 22 May 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 天津市地方志办公室 (1 August 2006). "第一章 干线\第一节 京山线". 天津通志·铁路志 (pdf). 天津社会科学院出版社. ISBN 9787805638935. Archived from the original on 12 January 2019. Retrieved 18 April 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 "China's First Railway – The Imperial Railways of North China 1880–1911" by A.L. Rosembaum, (unpublished Yale thesis 1972)>

- ↑ "京奉铁路八百多公里修了五十三年". 辽宁省档案馆. 2 September 2010. Archived from the original on 20 April 2019. Retrieved 20 April 2019.

- 1 2 "唐胥铁路:中国铁路源头的前世今生". 河北新闻网. 17 August 2017. Archived from the original on 29 March 2019. Retrieved 29 March 2019.

- ↑ Claude William Kinder: "Railways and Collieries of North China" in: Minutes of Proceedings, Institution of Civil Engineers vol. ciii 1890/91 Paper No.2474

- ↑ Percy Horace Kent: "Railway Enterprise in China", London, 1907

- ↑ 卷三. 1905. pp. 23, 24, 28.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 黄清琦, 陈喜波 (13 March 2015). "京奉铁路之历史地理研究(1881-1912年)". 地理研究. 中国科学院地理科学与资源研究所. 33 (11): 2180–2194. doi:10.11821/dlyj201411017 (inactive 1 August 2023). ISSN 1000-0585. Archived from the original on 31 March 2019. Retrieved 10 June 2019.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of August 2023 (link) - 1 2 Institution of Civil Engineers vol. clx 1905 Paper No.3509: "Railway Construction in North China" by Edward Hulme Rigby BSc and William Orr Leitch AMICE

- ↑ "Railway Wonders of the World" – 'A Wonderful Chinese Railway The First Line to be Financed, Built and Operates Solely by Celestial Effort' by F.A. Talbot, London c.1913

- ↑ "Eminent Chinese of the Ch’ing Period 1644–1912", edited by Arthur W Hummel, United States Government Printing Office, 1943.

- ↑ China's Early Industrialization: Shang Hsuan-huai (1844–1916), A Feuerwerker, Harvard University Press 1958.

- ↑ 张春燕 (2011). "京奉铁路述考". 兰台世界 (5): 43–44. doi:10.16565/j.cnki.1006-7744.2011.05.031.

- ↑ 王铁崖 (1957). 中外旧约章汇编第二册. 北京市: 生活·读书·新知三联书店. pp. 39–46.

- ↑ 日本关东军都督府陆军部 (1915). 第八卷. 东京: 陆军省. pp. 1–10.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ 宓汝成 (1963). 1863–1911(第二册). 北京: 中华书局. pp. 574–575.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ 日本关东军都督府陆军部 (1915). 第八卷. 东京: 陆军省. pp. 21, 22, 258, 259.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ 日本参谋本部 (1914). 第十卷. 东京: 偕行社. pp. 605, 606.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ 日本关东军都督府陆军部 (1915). 第七卷. 东京: 陆军省. pp. 55, 56.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ 日本外务省. 第一巻. 外務省外交史料館. pp. 编号1-7-3-106.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ 宓汝成 (1963). 1863–1911(第二册). 北京市: 中华书局.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ "从辽代移民到京奉铁路:沈阳历经了怎样的沧桑变迁?_网易新闻". 北京晚报. 网易新闻. 9 February 2018. Archived from the original on 12 April 2019. Retrieved 12 April 2019.

- ↑ "資料連結". Archived from the original on 22 December 2012. Retrieved 19 December 2021.

- ↑ "辛亥滦州起义烈士陵园纪实". Guangming_Online. 19 April 2011. Archived from the original on 3 June 2019. Retrieved 3 June 2019.

- ↑ 郭铁桩 (2009). "九一八事变后满铁攫取我国东北铁路路权始末". 齐齐哈尔大学学报(哲学社会科学版) (1): 122–124. doi:10.13971/j.cnki.cn23-1435/c.2009.01.050.

- ↑ 张洁 (2009). ""九一八"事变后日本攫取中国东北铁路权探析". 辽宁大学学报(哲学社会科学版). 37 (6): 48–52.

- ↑ 诵唐:《华北开发公司之伟绩》,《中联银行月刊》第7卷第3期, 1944年3月,第48页。

- ↑ 中国铁路史编辑研究中心 (1996). 中国铁路大事记. 北京市: 中国铁道出版社. p. 28.

- ↑ "Royal Engineers Journal" : 1 October 1901, January 1903, and September 1903 and also Royal Engineers Archives, Chatham, Kent: "British Railway Administration Reports" for the Peking-Shanhaikuan Railway, February 1901 to September 1902.

- ↑ "Who’s Who" in The China Year Book 1921–1922, edited by H.G.W. Woodhead, Tientsin Press.

- ↑ "The Chinese Times" 30 March 1889 edition, published in Shanghai

- ↑ "Chronicle & Directory for China, Corea, Japan, The Philippines etc." years: 1880–1890