Paul Pelliot | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Paul Pelliot | |||||||||||

| Born | 28 May 1878 | ||||||||||

| Died | 26 October 1945 (aged 67) Paris, France | ||||||||||

| Known for | Dunhuang manuscripts discovery | ||||||||||

| Scientific career | |||||||||||

| Fields | Chinese history | ||||||||||

| Institutions | Collège de France École Française d'Extrême-Orient | ||||||||||

| Academic advisors | Édouard Chavannes Sylvain Lévi | ||||||||||

| Notable students | Paul Demiéville | ||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||

| Chinese | 伯希和 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

Paul Eugène Pelliot[1] (28 May 1878 – 26 October 1945) was a French Sinologist and Orientalist best known for his explorations of Central Asia and his discovery of many important Chinese texts such as the Dunhuang manuscripts.

Early life and career

Paul Pelliot was born on 28 May 1878 in Paris, France, and initially intended to pursue a career as a foreign diplomat.[2] Accordingly, he studied English as a secondary school student at La Sorbonne, then studied Mandarin Chinese at the École des Langues Orientales Vivantes (School of Living Oriental Languages).[2] Pelliot was a gifted student, and completed the school's three-year Mandarin course in only two years.[2] His rapid progress and accomplishments attracted the attention of the Sinologist Édouard Chavannes, the chair of Chinese at the Collège de France, who befriended Pelliot and began mentoring him. Chavannes also introduced Pelliot to the Collège's Sanskrit chair, Sylvain Lévi.[2] Pelliot began studying under the two men, who encouraged him to pursue a scholarly career instead of a diplomatic one.[2]

In early 1900, Pelliot moved to Hanoi to take up a position as a research scholar at the École Française d'Extrême-Orient (EFEO, "French School of the Far East").[2] In February of that year, Pelliot was sent to Peking (modern Beijing) to locate and buy Chinese books for the school's library.[2] Between July and August 1900, Pelliot was caught up in the siege of the foreign legations during the Boxer Rebellion.[2] At one point, during a ceasefire, Pelliot made a daring one-man foray to the rebels' headquarters, where he used his boldness and fluency in Mandarin to impress the besiegers into giving him fresh fruit for those inside the legation.[2] For his conduct during the siege, as well as for capturing an enemy flag during the fighting, he was awarded the Légion d'Honneur upon his return to Hanoi.[2] In 1901, when only 23 years old, Pelliot was made a professor of Chinese at the EFEO.

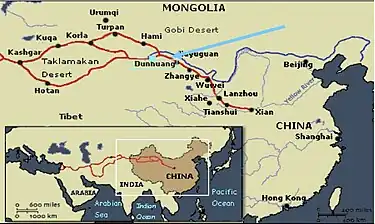

Pelliot stayed in Hanoi until 1904, when he returned to France in preparation for representing the EFEO at the 1905 International Conference of Orientalists in Algiers.[3] While in France, Pelliot was chosen to direct a government-sponsored archaeological mission to Chinese Turkestan (modern Xinjiang).[3] The group departed in June 1906 and spent several years in the field (see below).[3] By the time the expedition reached Dunhuang, Pelliot had learned Mongolian, Arabic, Persian, the Turkic languages, Tibetan, and Sanskrit, among others, which proved invaluable while examining the many non-Chinese items among the Dunhuang manuscripts inside the Mogao caves.[4]

Central Asia expedition

Pelliot's expedition left Paris on 17 June 1906. His three-man team included Dr. Louis Vaillant, an Army medical officer, and Charles Nouette, a photographer. Aboard the train in Samarkand, the Frenchmen met Baron Gustaf Mannerheim, a colonel in the Russian Imperial Army and the last Tsarist agent in the Great Game. Pelliot had agreed to allow the army officer, disguised as an ethnographic collector, to travel with his expedition. Mannerheim was actually carrying out a secret mission for Tsar Nicholas II to collect intelligence on the reform and modernization of the Qing Dynasty.[5] The Tsar was assessing the possibility of a Russian invasion of Western China. Pelliot fully endorsed Mannerheim's participation, and even offered himself as an informant to the Russian General Staff. In return, the Frenchman demanded free passage on the Trans-Caspian Railway, a personal and confidential payment of ten thousand francs and a Cossack escort. These were granted, and the payment even doubled.[6]

The expedition traveled to Chinese Turkestan by rail through Moscow and Tashkent to Andijan, where they mounted horses and carts to Osh. From here, they travelled across the Alai Mountains of southern Kyrgyzstan over the Taldyk Pass and Irkeshtam Pass to China. Near the town of Gulcha, the expedition met Kurmanjan Datka, the famed Muslim Queen of Alai and posed for a photograph with her.[8] Mannerheim and Pelliot did not get along, and parted ways two days after leaving Irkeshtam Pass.[9] The French team arrived in Kashgar at the end of August, staying with the Russian consul-general (the successor to Nikolai Petrovsky). Pelliot amazed the local Chinese officials with his fluent Chinese (only one of the 13 languages he spoke). His efforts were to pay off shortly, when his team began obtaining supplies (like a yurt) previously considered unobtainable.

His first stop after leaving Kashgar was Tumxuk. From there, he proceeded to Kucha, where he found documents in the lost language of Kuchean. These documents were later translated by Sylvain Lévi, Pelliot's former teacher. After Kucha, Pelliot went to Ürümqi, where they encountered Duke Lan, whose brother had been a leader of the Boxer Rebellion. Duke Lan, who was the deputy chief of the Peking gendarmerie and participated in the siege, was in permanent exile in Ürümqi.[10]

In Ürümqi, Pelliot heard about a find of manuscripts at the Silk Road oasis of Dunhuang from Duke Lan. The two had a bittersweet reunion. Pelliot had been in the French legation in Peking while Duke Lan and his soldiers were besieging the foreigners during the Boxer Rebellion. They reminisced about old times and drank champagne. Duke Lan also presented Pelliot with a sample Dunhuang manuscript. Recognizing its antiquity and archaeological value, Pelliot quickly set off for Dunhuang, but arrived there months after the Hungarian-British explorer Aurel Stein had already visited the site.[11]

At Dunhuang, Pelliot managed to gain access to Abbot Wang's secret chamber, which contained a massive hoard of medieval manuscripts. Stein had first seen the manuscripts in 1907 and had purchased a large number of them. However, Stein had no knowledge of the Chinese language, and had no way to be selective in which documents he purchased and took back to Britain. Pelliot, on the other hand, had an extensive command of Classical Chinese and numerous other Central Asian languages, and spent three weeks during April 1908 examining manuscripts at breakneck speed.[3] Pelliot selected what he felt were the most valuable of the manuscripts, and Wang, who was interested in continuing the refurbishment of his monastery, agreed to sell them to Pelliot for a price of 500 taels (roughly equivalent to US$11,000 in 2014).

Return and later years

Pelliot returned to Paris on 24 October 1909 to a vicious smear campaign mounted against himself and Édouard Chavannes. While at Dunhuang, Pelliot had written a detailed account of some of the most valuable documents he had found and mailed it back to Europe, where it was published upon its arrival.[4] In the report, Pelliot included extensive biographical and textual data and precise dates from many of the manuscripts, which he had examined for only a few minutes each and then later recalled their details from memory while writing his report.[4] That intellectual feat was so astonishing that many who were unfamiliar with Pelliot and his prodigious memory believed he had faked all the manuscripts and written his report from a library full of reference books.[4] Pelliot was publicly accused of wasting public money and returning with forged manuscripts. The campaign came to a head with a December 1910 article in La Revue Indigène by Fernand Farjenel (d. 1918) of the Collège libre des sciences sociales. At a banquet on 3 July 1911, Pelliot struck Farjenel, and a court case followed.[12] The charges were not proven false until the Hungarian-British explorer Aurel Stein's book, Ruins of Desert Cathay, appeared in 1912. In his book, Stein supported Pelliot's accounts and made it clear that he had left manuscripts behind in Dunhuang after his visit, which vindicated Pelliot and silenced his critics.

In 1911, as recognition of Pelliot's broad and unique scholarship, the Collège de France made him a professor and created a special chair for him: the Chair of the Languages, History, and Archaeology of Central Asia.[13] The chair was never filled after Pelliot's death, leaving him the only person to have ever held it.[13] In 1920, Pelliot joined Henri Cordier as co-editor of the preeminent sinological journal T'oung Pao, serving until 1942.[14] After Cordier's death in 1924, Pelliot edited T'oung Pao alone until he was joined by Dutch sinologist J. J. L. Duyvendak in 1932.[14]

Pelliot served as French military attaché in Peking during World War I. He died of cancer in 1945. Upon his death, it was said "Without him, sinology is left like an orphan".

The Guimet Museum in Paris has a gallery named after him.

Works and publications

- Tamm, Eric Enno. "The Horse That Leaps Through Clouds: A Tale of Espionage, the Silk Road and the Rise of Modern China". Vancouver, Douglas & Mcintyre, 2010. ISBN 978-1-55365-269-4.

- Trois Ans dans la haute Asie 1910. Trois Ans dans la haute Asie : vol.1

- Pelliot (with E. Chavannes), "Un traité manichéen retrouvé en Chine", Journal asiatique 1911, pp. 499–617; 1913, pp. 99–199, 261–392.

- " Les influences iraniennes en Asie Centrale et en Extrême-Orient," Revue d'histoire et de littérature religieuses, N.S. 3, 1912, pp. 97–119.

- "Mo-ni et manichéens," Journal asiatique 1914, pp. 461–70.

- "Le 'Cha-tcheou-tou-fou-t'ou-king' et la colonie sogdienne de la region du Lob Nor", Journal asiatique 1916, pp. 111–23.

- "Le sûtra des causes et des effets du bien et du mal". Edité‚ et traduit d'après les textes sogdien, chinois et tibétain par Robert Gauthiot et Paul Pelliot, 2 vols (avec la collaboration de E. Benveniste), Paris, 1920.

- Les grottes de Touen-Houang 1920. Les grottes de Touen-Houang : vol.1 Les grottes de Touen-Houang : vol.2 Les grottes de Touen-Houang : vol.3 Les grottes de Touen-Houang : vol.4 Les grottes de Touen-Houang : vol.5 Les grottes de Touen-Houang : vol.6

- "Les Mongols et la Papauté. Documents nouveaux édités, traduits et commentés par M. Paul Pelliot" avec la collaboration de MM. Borghezio, Masse‚ and Tisserant, Revue de l'Orient chrétien, 3e sér. 3 (23), 1922/23, pp. 3–30; 4(24), 1924, pp. 225–335; 8(28),1931, pp. 3–84.

- "Les traditions manichéennes au Foukien," T'oung Pao, 22, 1923, pp. 193–208.

- "Neuf notes sur des questions d'Asie Centrale," T'oung Pao, 24, 1929, pp. 201–265.

- Notes sur Marco Polo, ed. L. Hambis, 3 vols., Paris 1959–63.

- Notes on Marco Polo, (English version), Imprimerie nationale, librairie Adrien-Maisonneuve, Paris. 1959-63 Notes on Marco Polo : vol.1 Notes on Marco Polo : vol.2 Notes on Marco Polo : vol.3

- "Recherches sur les chrétiens d'Asie centrale et d'Extrême-Orient I, Paris, 1973.

- "L'inscription nestorienne de Si-ngan-fou", ed. avec supléments par Antonino Forte, Kyoto et Paris, 1996.

- P. Pelliot et L. Ηambis, "Histoire des campagnes de Gengizkhan", vol. 1, Leiden, 1951.

- * Marco Polo: The Description of the World. 1938. Translated and edited by A. C. Moule & Paul Pelliot. 2 Volumes. George Routledge & Sons, London. Downloadable from ISBN 4-87187-308-0 Marco Polo : vol.1 Marco Polo : vol.2

- Marco Polo Transcription of the Original in Latin (with Arthur Christopher Moule) ISBN 4-87187-309-9

- P. Pelliot, "Artistes des Six Dynasties et des T’ang", T’oung Pao 22, 1923.

- "Quelques textes chinois concernant l'Indochine hindouisśe." 1925. In: Etudes Asiatiques, publiées à l'occasion du 25e anniversaire de l'EFEO.- Paris: EFEO, II: 243–263.

See also

References

Citations

- ↑ Name as given in the Legion d'honneur recipient database

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Honey (2001), p. 59.

- 1 2 3 4 Honey (2001), p. 64.

- 1 2 3 4 Honey (2001), p. 65.

- ↑ Tamm 2010, p. 59

- ↑ Tamm 2010, p. 60

- ↑ Pelliot, Paul Emile (1909). Trois Ans dans la haute Asie : vol.1 / Page 13 (Color Image). pp. 7–8.

- ↑ Tamm 2010, p. 89

- ↑ Tamm 2010, p. 108

- ↑ Tamm 2010, p. 179

- ↑ Tamm 2010, p. 201

- ↑ "100, 75, 50 Years Ago". The New York Times. 26 October 2011. Retrieved 11 December 2012.

- 1 2 Honey (2001), p. 66.

- 1 2 Honey (2001), p. 78.

Sources

- Honey, David B. (2001). Incense at the Altar: Pioneering Sinologists and the Development of Classical Chinese Philology. American Oriental Series. Vol. 86. New Haven, CT: American Oriental Society. ISBN 0-940490-16-1.

- Hopkirk, Peter (1980). Foreign Devils on the Silk Road: The Search for the Lost Cities and Treasures of Chinese Central Asia. Amherst, MA: The University of Massachusetts Press. ISBN 0-87023-435-8.

- Tamm, Eric Enno (2010). The Horse That Leaps Through Clouds: A Tale of Espionage, the Silk Road and the Rise of Modern China. Vancouver, BC: Douglas & Mcintyre. ISBN 978-1-55365-269-4.

- Walravens, Hartmut (2001). Paul Pelliot (1878–1945): His Life and Works - A Bibliography. Indiana University Oriental Studies IX. Bloomington, IN: Research Institute for Inner Asian Studies. ISBN 0-933070-47-0.

External links

- New York Times 28 January 1909

- French video Paul Pelliot and the chinese national treasure

- E. Bruce Brooks, "Paul Pelliot," (June 9, 2004) Sinological Profiles Warring States Project, University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

- About 300 books and papers of Paul Pelliot available for download on Monumenta Altaica web-site