| New York Tunnel Extension | |||

|---|---|---|---|

North Bergen portal of the tunnels | |||

| Overview | |||

| Status | In operation | ||

| Owner | Amtrak | ||

| Locale | New York City Hudson County, New Jersey | ||

| Service | |||

| Type | Heavy rail, Commuter rail | ||

| System | Originally Pennsylvania Railroad now Amtrak, New Jersey Transit, Long Island Rail Road. | ||

| History | |||

| Opened | 1910 | ||

| Technical | |||

| Line length | 44 miles (71 km) (total main line trackage) | ||

| Track gauge | 1,435 mm (4 ft 8+1⁄2 in) standard gauge | ||

| Electrification | 650 V DC third rail (1910–1933). 11,000 V AC overhead lines (1933-present) | ||

| |||

The New York Tunnel Extension (also New York Improvement and Tunnel Extension) is a combination of railroad tunnels and approaches from New Jersey and Long Island to Pennsylvania Station in Midtown Manhattan.

It was built by Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR) at the beginning of the 20th century to improve railroad access throughout the greater New York City area,[1] and led to the line's then-new passenger facility, Pennsylvania Station.

Planning

The PRR had consolidated its control of railroads in New Jersey with the lease of United New Jersey Railroad and Canal Company in 1871, thereby extending its rail network from Philadelphia northward to Jersey City. Crossing the Hudson River, however, remained a major obstacle. To the east, the Long Island Rail Road (LIRR) ended at the East River. In both situations, passengers had to transfer to ferries to Manhattan. This put the PRR at a disadvantage relative to its closest competitor, the New York Central Railroad, which already served Manhattan via its Grand Central Station.[2][3]: 28

Early tunnel and bridge proposals

Various plans to build a physical link across the Hudson River were discussed as early as the 1870s, and both tunnel and bridge projects were considered by the railroads and government officials.[4]: 200 A tunnel project for the Hudson and Manhattan Railroad (H&M), a rapid transit line, began in 1874, and encountered serious engineering, financial and legal obstacles. The project was halted in 1880 after a blowout accident that cost 20 lives.[5] (Work on the H&M tunneling project, later known as the Uptown Hudson Tubes, continued intermittently but was not completed until 1906;[6] it was opened to passenger trains in 1908.[7])

The technology of tunnel-building was still primitive and risky in the 1880s, and this gave impetus to a major bridge design proposal promoted by engineer Gustav Lindenthal.[8]: 20 [4]: 200 The bridge would be situated between Hoboken, New Jersey and 23rd Street in Manhattan. However, due to the congested shipping conditions in New York Harbor, the design called for an enormous bridge span that would have been twice that of the Brooklyn Bridge. At one point, plans for the bridge called for it to carry 14 tracks.[3]: 29 Although Congress granted Lindenthal's company a charter in 1890 for construction of a bridge, the huge $27 million project cost would have to be shared by several railroads.[9] The Panic of 1893 made large capital investments nearly impossible for some time, as one third of the nation's railroads failed.[8]: 20 [4]: 200 Some foundation masonry was laid on the Hoboken side in 1895, but the PRR was unsuccessful in getting other companies to share in the expenses, and the bridge project was abandoned.[9]

Revised plans

The PRR, working with the LIRR, developed several new proposals for improved regional rail access in 1892.[10] They included construction of new tunnels between Jersey City and Manhattan, and possibly a tunnel via Brooklyn and the East River; new terminals in midtown Manhattan for both the PRR and LIRR; completion of the Hudson Tubes; and a bridge proposal.[9] These ideas were discussed extensively for several years but did not come to fruition until the turn of the century. In 1901 the PRR took great interest in a new railroad approach just completed in Paris. In the Parisian railroad scheme, electric locomotives were substituted for steam locomotives prior to the final approach into the city. PRR President Alexander Johnston Cassatt, upon his return from Paris, adapted the method for the New York City area in the form of the New York Tunnel Extension project, which he created and led the overall planning effort for.[3]: 29 The PRR, who had been working with the LIRR on the Tunnel Extension plans, made plans to acquire majority control of the LIRR so that one new terminal, rather than two, could be built in Manhattan.[9] The PRR acquired the LIRR in 1900.[11][3]: 30 A board was created to study each of the proposals to bring the PRR directly into New York. The team ultimately found that a direct approach was better than any of the alternatives.[3]: 29

The original proposal for the PRR and LIRR terminal in Midtown, which was published in June 1901, called for the construction of a bridge across Hudson River between 45th and 50th Streets in Manhattan, as well as two closely spaced terminals for the LIRR and PRR. This would allow passengers to travel between Long Island and New Jersey without having to switch trains.[12] In December 1901, the plans were modified so that the PRR would construct the North River Tunnels under the Hudson River, instead of a bridge over it.[13] The PRR cited costs and land value as a reason for constructing a tunnel rather than a bridge, since the cost of a tunnel would be one-third that of a bridge. The North River Tunnels themselves would consist of between two and four steel tubes with the diameter of 18.5 to 19.5 feet (5.6 to 5.9 m).[14] The New York Tunnel Extension quickly gained opposition from the New York City Board of Rapid Transit Commissioners, who objected that they would not have jurisdiction over the new tunnels, as well as from the Interborough Rapid Transit Company, which saw the New York Tunnel Extension as a potential competitor to its as-yet-incomplete rapid transit service.[15] The project was approved by the New York City Board of Aldermen in December 1902, on a 41-36 vote. The North and East River Tunnels were to be built under the riverbed of their respective rivers. The PRR and LIRR lines would converge at New York Penn Station, an expansive Beaux-Arts edifice between 31st and 33rd Streets in Manhattan. The entire project was expected to cost over $100 million.[16]

The PRR created subsidiaries to manage the project. The Pennsylvania, New Jersey and New York Railroad and the Pennsylvania, New York and Long Island Rail Road, were the New Jersey and New York parts, respectively. The PNJ&NY was incorporated February 13, 1902, and the PNY&LI was incorporated April 21, 1902. They were consolidated into the Pennsylvania Tunnel and Terminal Railroad (PT&T) on June 26, 1907.[9]

Design and construction

The design and construction aspects of the project were organized into three principal divisions: the Meadows, North River, and East River divisions.[17][18] As of 2021, there are revived plans to renovate and expand the Meadows and North River divisions as part of the Gateway Program.

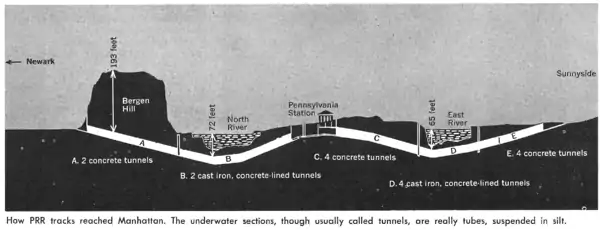

Meadows Division

The original PRR route in New Jersey ran to the Exchange Place ferry terminal in Jersey City. The Meadows Division project built a new, approximately 5-mile (8.0 km) route from the PRR main line at Harrison, New Jersey, northeast to the west end of the new tunnels. This involved constructing a new station at Harrison, Manhattan Transfer, along with a rail yard, to provide for changing between steam and electric locomotives. Northeast from this new station the double track line was built. It crossed over the Hudson and Manhattan Railroad and Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad on the Sawtooth Bridges; the Hackensack River on the Portal Bridge; and on embankment through the Hackensack Meadowlands to the west portal of the tunnels under Bergen Hill in the Palisades.[19][3]: 29

North River Division

The North River Division ran from the west portal of the tunnels to Manhattan. The PRR ultimately decided to build a pair of single-track tunnels under the river, called the North River Tunnels, between Weehawken and midtown Manhattan; the two tunnels continued seamlessly west from Weehawken to the west portals.[4]: 200 [3]: 29 In later years "North River Tunnels" came to refer to the whole length of tunnel from the western portal in North Bergen to 10th Avenue in Manhattan. The two tracks fan out to 21 tracks just west of Penn Station.[20][21]: 399 [3]: 76

Construction on the North River tunnels began in 1904 under the supervision of O'Rourke Engineering and Construction Company.[22][3]: 33 Boring operations were completed on October 9, 1906.[23] Service from New Jersey to Manhattan began on November 27, 1910, once Penn Station was completed.[24]

East River Division

The East River Division managed construction of tunnels running across Manhattan, and under the East River to Queens. The East River Tunnels are four single-track tunnels that extend from the eastern end of Pennsylvania Station and cross the East River.[3]: 29 East of the station, tracks 5–21 merge into two 3-track tunnels, which then merge into the East River Tunnels' four tracks. The tunnels end and the tracks rise to ground level east of the Queens shoreline.[20] The tunnels connect to Sunnyside Yard, a large 75-acre (30 ha) coach yard that could hold up to 1,550 train carriages. Construction proceeded concurrently with the North River tunnels.[2][4]: 201 [3]: 20

The tunnels were built by S. Pearson and Son, the same company who had built the Uptown Hudson Tubes.[22][3]: 33 The tunnel technology was so innovative that in 1907 the PRR shipped an actual 23-foot (7.0 m) diameter section of the new East River Tunnels to the Jamestown Exposition in Norfolk, Virginia, to celebrate the 300th anniversary of the nearby founding of the colony at Jamestown.[25] The same tube, with an inscription indicating that it had been displayed at the Exposition, was later installed under water and remains in use. Construction was completed on the East River tunnels on March 18, 1908.[26] LIRR service to Penn Station began on September 8, 1910.[27]

Operation during the PRR era

By the time construction was complete, the total project cost for the station and associated tunnels was $114 million (equivalent to $2.6 billion in 2022[28]), according to an Interstate Commerce Commission report.[29]: 156–157 [3]: 29

The North River Tunnels carried PRR trains under the Hudson; for some years PRR electric engines also pulled Lehigh Valley Railroad or Baltimore and Ohio Railroad trains to New York. The East River Tunnels carried LIRR and PRR trains to the Sunnyside Yard in Queens.[3]: 30 As part of the New York Connecting Railroad improvement project, a connection from the East River Tunnels to the New Haven Railroad tracks was also built. New Haven trains began running through the East River Tunnels, serving Penn Station, in 1917 after the Hell Gate Bridge opened.[3]: 30 [20]

The electrification of the New York Tunnel Extension, including the station, was initially 600-volt direct-current third rail.[3]: 29 It was later changed to 11,000V alternating-current overhead catenary when electrification of PRR's mainline was extended to Washington, D.C., in the early 1930s.[30] In New Jersey the third rail ended at Manhattan Transfer, where all trains stopped to change steam and electric engines.[3]: 52 Two electrical substations were built for the project: one in Harrison, New Jersey, and the other in Long Island City, New York.[20]

After the New York Tunnel Extension opened, some PRR suburban trains continued to serve the Exchange Place station, where passengers could board the PRR ferry, or the Hudson Tube system (later called PATH), to downtown Manhattan.[3]: 54 The ferry from Exchange Place ended service in 1949,[31] and the Exchange Place PRR terminal closed in 1961.[32]

One branch, the freight-only Harrison Branch, split off the line just east of its west end and ran west to a connection with the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad's Harrison Cut-off and the Erie Railroad's Paterson and Newark Branch.

Trackage rights

The following non-PRR railroads used the line:

Operation by successor railroads

The PRR merged into Penn Central Transportation in 1968.[34] All of Penn Central's property was conveyed to Amtrak on April 1, 1976, when Conrail's system was formed.[35] The Tunnel Extension is now part of Amtrak's Northeast Corridor; New Jersey Transit and the Long Island Rail Road use the western and eastern sections, respectively, to reach New York Penn Station.[36]

See also

- Access to the Region's Core – tunnel project, canceled in 2010

- Cross-Harbor Rail Tunnel – project proposed in 1993

- East Side Access – tunnel project, completed in 2023

- Gateway Project – project proposed in 2011

- New York Connecting Railroad – follow-up to Tunnel Extension, completed in 1917

- Penn Station Access – proposed project

References

- ↑ American Society of Civil Engineers.; Gibbs, George. (1910). The New York tunnel extension of the Pennsylvania Railroad; station construction, road, track, yard equipment, electric traction, and locomotives. New York.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - 1 2 Schafer, Mike; Brian Solomon (2009) [1997]. Pennsylvania Railroad. Minneapolis, MN: Voyageur Press. pp. 61–64. ISBN 978-0-7603-2930-6. OCLC 234257275.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Cudahy, Brian J. (2002), Rails Under the Mighty Hudson (2nd ed.), New York: Fordham University Press, ISBN 978-0-82890-257-1, OCLC 911046235

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Opening of the Pennsylvania Terminal Station in New York". Scientific American. 103 (11): 200–201. September 10, 1910. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican09101910-200. Retrieved February 29, 2020.

- ↑ Burr, S.D.V. (1885). Tunneling Under The Hudson River: Being a description of the obstacles encountered, the experience gained, the success achieved, and the plans finally adopted for rapid and economical prosecution of the work. New York: John Wiley and Sons. p. 24 ff.

- ↑ "Under the Hudson River by Tunnel About to Become a Reality; October 1 Will See the End of a Romance of Thirty-four Years' Struggle of Capital and Brains Against the Seemingly Insurmountable Obstacles of Nature". The New York Times. May 26, 1907. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 24, 2018.

- ↑ "TROLLEY TUNNEL OPEN TO JERSEY; President Turns On Power for First Official Train Between This City and Hoboken. REGULAR SERVICE STARTS Passenger Trains Between the Two Cities Begin Running at Midnight. EXERCISES OVER THE RIVER Govs. Hughes and Fort Make Congratulatory Addresses -- Dinner at Sherry's in the Evening". The New York Times. February 26, 1908. Retrieved April 24, 2018.

- 1 2 Jonnes, Jill (2007). Conquering Gotham - A Gilded Age Epic: The Construction of Penn Station and its Tunnels. New York: Viking. ISBN 978-0-670-03158-0.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Couper, William. (1912). History of the Engineering Construction and Equipment of the Pennsylvania Railroad Company's New York Terminal and Approaches. New York: Isaac H. Blanchard Co. pp. 7–16.

- ↑ "The Project Gutenberg eBook of The New York Tunnel Extension of the Pennsylvania Railroad, The North River Division, By Charles M. Jacobs". www.gutenberg.org. Retrieved October 11, 2020.

- ↑ "PENNSYLVANIA'S NEW PLANS OUTLINED; Big Improvements to be Made in Long Island's Acquisition. NO THOUGHT OF MONTAUK POINT Ferry Connection from Jersey City to Bay Ridge and Tunnels to Follow, an Official Says". The New York Times. May 8, 1900. Retrieved May 23, 2018.

- ↑ "NORTH RIVER BRIDGE PLAN; Pennsylvania Road Negotiating with Banking Houses". The New York Times. June 26, 1901. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- ↑ "PENNSYLVANIA'S TUNNEL UNDER NORTH RIVER; Property Already Acquired for the Great New York Terminal. TO PUSH THE CONSTRUCTION City Neighborhoods' to be Improved -- Depth of the Tunnel So Great Subways Will Not Be Obstructed". The New York Times. December 12, 1901. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- ↑ "PENNSYLVANIA'S TUNNEL A SUBMERGED BRIDGE; New York Terminal to be a Magnificent Structure. DETAILED PLANS DISCLOSED Vice President Rea Credited with the Idea Which Will, Experts Believe, Advance the City's Interests to an Unparalleled Degree". The New York Times. December 13, 1901. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- ↑ "MORE OPPOSITION TO PENNSYLVANIA'S BILL; Rapid Transit Commissioners Will Appear Against It. THEIR RIGHTS INFRINGED E.M. Shepard and A.B. Boardman, Counsel for Board, Say that It Af- fects That Body's Usefulness -- Mr. Cassatt's Views". The New York Times. March 21, 1902. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- ↑ "PENNSYLVANIA TUNNEL FRANCHISE PASSED; Aldermen Approve the Grant by a Vote of 41 to 36 Borough President Cantor Speaks and Votes Against the Measure -- Excited Debate Before the Final Action. PENNSYLVANIA TUNNEL FRANCHISE PASSED". The New York Times. December 17, 1902. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- ↑ Keys, C. M. (July 1910). "Cassatt And His Vision: Half A Billion Dollars Spent In Ten Years To Improve A Single Railroad - The End Of A Forty-Year Effort To Cross The Hudson". The World's Work: A History of Our Time. XX: 13187–13204. Retrieved July 10, 2009.

- ↑ "Nearly Twenty Miles Through Tubes and Tunnels" (PDF). New York Times. November 9, 1908. Retrieved February 27, 2011.

- ↑ Raymond, Charles W. (September 1910). "The New York Tunnel Extension of the Pennsylvania Railroad". Transactions of the American Society of Civil Engineers. 68 (3): 1–31. doi:10.1061/TACEAT.0002217. Paper No. 1150.

- 1 2 3 4 Mills, William Wirt (1908). Pennsylvania Railroad tunnels and terminals in New York City. Moses King. Retrieved May 26, 2018.

- ↑ "Completion of the Pennsylvania Tunnels and Terminal Station". Scientific American. Library of American civilization. Munn & Company (v. 102). May 14, 1910. Retrieved May 24, 2018.

- 1 2 "O'ROURKE WILL BUILD PENNSYLVANIA TUNNEL; New York Firm Gets Contract for North River Section. BRITISH TO BORE OTHER TUBE S. Pearson & Son, Limited, of London, the Successful Bidders for Work Under the East River". The New York Times. March 12, 1904. Retrieved May 23, 2018.

- ↑ "THE PENNSYLVANIA OPENS ITS SECOND RIVER TUBE; A Real Experience Tramping Through the Bores. HEADINGS MEET EXACTLY Brief Ceremonies as the Engineers Pass the Shield of the New North River Section. THE PENNSYLVANIA OPENS ITS SECOND RIVER TUBE". The New York Times. October 10, 1906. Retrieved May 23, 2018.

- ↑ "PENNSYLVANIA OPENS ITS GREAT STATION; First Regular Train Sent Through the Hudson River Tunnel at Midnight". The New York Times. November 27, 1910. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 23, 2018.

- ↑ Industrial Magazine. Geo. S. Mackintosh. 1907. p. 79. Retrieved May 23, 2018.

- ↑ "FOURTH RIVER TUBE THROUGH; Last of Pennsylvania-Long Island Tunnels Connected -- Sandhogs Celebrate". The New York Times. March 19, 1908. Retrieved May 23, 2018.

- ↑ "DAY LONG THRONG INSPECTS NEW TUBE; 35,000 Persons Were Carried on the First Day of Pennsylvania's Tunnel Service. ACCIDENT MARRED OPENING Morning Trains Delayed Two Hours by Broken Third Rail -- Some Complaints Over Extra Fare". The New York Times. September 9, 1910. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- ↑ Johnston, Louis; Williamson, Samuel H. (2023). "What Was the U.S. GDP Then?". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved November 30, 2023. United States Gross Domestic Product deflator figures follow the Measuring Worth series.

- ↑ Droege, John A. (1916). Passenger Terminals and Trains. New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 156.

droege Passenger Terminals and Trains.

- ↑ Donovan, Frank P. Jr. (1949). Railroads of America. Milwaukee: Kalmbach Publishing.

- ↑ Adams, A.G. (1996). The Hudson Through the Years. Fordham University Press. p. 307. ISBN 978-0-8232-1677-2. Retrieved May 26, 2018.

- ↑ "JERSEY CITY DEPOT CLOSED BY PENNSY; Trains to Exchange Plac Will Now Come Here". The New York Times. November 18, 1961. Retrieved May 26, 2018.

- ↑ "B&O Railroad Museum".

- ↑ "Court Here Lets Railroads Consolidate Tomorrow; RAIL MERGER GETS FINAL CLEARANCE" (PDF). The New York Times. 1968. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 1, 2018.

- ↑ Bedingfield, Robert E. (April 1, 1976). "Conrail Takes Over Northeast's System". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 5, 2018.

- ↑ Nowakowski, Patrick (April 24, 2017). Metro-North/LIRR Committee Meeting (Board meeting). Event occurs at 15:45. Retrieved April 29, 2017.

Bibliography

- Clarke, George C. (September 1910). "The New York Tunnel Extension of the Pennsylvania Railroad. The Site of the Terminal Station". Transactions of the American Society of Civil Engineers. LXVIII.

- Noble, Alfred (September 1910). "The New York Tunnel Extension of the Pennsylvania Railroad. The East River Division". Transactions of the American Society of Civil Engineers. 68. Paper No. 1152.

- Temple, E.B. (September 1910). "The New York Tunnel Extension of the Pennsylvania Railroad. Meadows Division and Harrison Transfer Yard". Transactions of the American Society of Civil Engineers. 68. doi:10.1061/TACEAT.0002218. Paper No. 1153.

- Lavis, F. (September 1910). "The New York Tunnel Extension of the Pennsylvania Railroad. The Bergen Hill Tunnels". Transactions of the American Society of Civil Engineers. 68. Paper No. 1154.

- Brace, James H.; Mason, Francis (September 1910). "The New York Tunnel Extension of the Pennsylvania Railroad. The Cross-Town Tunnels". Transactions of the American Society of Civil Engineers. 68. Paper No. 1158.

- Brace, James H.; Mason, Francis; Woodard, S.H. (September 1910). "The New York Tunnel Extension of the Pennsylvania Railroad. The East River Tunnels". Transactions of the American Society of Civil Engineers. 68. Paper No. 1159.

- Gilbert, G.H.; Whiteman, L.I. (1912), The Subways and Tunnels of New York, Wiley and Sons, ISBN 9785876055989