The Conestoga was a launch vehicle design funded by Space Services Inc. of America (SSIA) of Houston, Texas. Conestoga originally consisted of surplus LGM-30 Minuteman stages with additional strap-on boosters, as required for larger payloads. It was the world's first privately funded commercial rocket, but was launched only three times (once as a modified design) between 1981 and 1995,[1][2] before the program was shut down.

History

Percheron

SSIA had originally intended to use a design by Gary Hudson, Percheron, which was intended to dramatically lower the price of space launches. Key to the design was a simple pressure-fed kerosene-oxidizer engine that was intended to reduce the cost of the expendable booster. Various loads could be accommodated by clustering the basic modules together. SSIA conducted an engine test firing of the Percheron on Matagorda Island on August 5, 1981, but the rocket exploded due to a malfunction.[3] SSIA then asked Hudson to become head of R&D at SSIA, but because they wished to focus on solid fuel rockets, he declined.[4]

Conestoga 1

SSIA founder David Hannah then hired Deke Slayton, one of the original Mercury Seven astronauts. Slayton had just left NASA after running the Space Shuttle Landing and Approach validation testing (among earlier roles). SSIA purchased an Aries research rocket from Space Vector, Inc., which was developed for the U.S. Navy and NASA using the second stage of the Minuteman missile, and used it develop the Conestoga 1.[5]

The first launch of the new Conestoga 1 design took place on 9 Sep 1982,[5] consisting of the core missile stage and a 500 kg dummy payload which included 40 gallons of water. The payload was successfully ejected at 313 km, and the Conestoga I became the first privately funded rocket to reach space.[6]

Starfire

SSIA launched a second rocket in 1989, a Black Brant sounding rocket which they referred to as Starfire,[7] to provide commercial support for microgravity experiments.

Conestoga 1620

SSIA was purchased by EER Systems in December 1990. The design was modified again, this time using Castor engines like those used on the Scout, a workhorse of the 1960s. The new design was known as the Conestoga with a four-digit number following it indicating the arrangement of the boosters.[8] The engine bells on the clustered boosters vary depending on their firing order; the larger bells are tuned for higher altitudes.

In May 1990 the Center for Space Transportation and Applied Research (CSTAR) pitched to NASA their Commercial Experiment Transporter (COMET) payload concept, a low-cost standardized bus with both suborbital and orbital components. Mission duration for the COMET would be longer than for existing sounding rockets, and the orbital portion would be free-flight and not disturbed by crew movement as it was on the Space Shuttle. Westinghouse agreed to provide the bus and "service module," Space Industries Inc. built the re-entry module, and EER was contracted to provide several Conestoga launchers.

The entire COMET program quickly ran into delays and budget overruns, and it was not until the end of the program that a COMET (now known as METEOR) and Conestoga 1620 were finally ready for launch.

The 1620 configuration was a four stage design, with two Castor-4B and two Castor-4A engines on the first stage; two Castor-4B on the second stage; one Castor-4B on the third stage and one Star-48V on the fourth stage.[8]

The satellite payload included a number of experiments, including material (evaluation of exposure to the harsh space environment) and biological (assessment of seed reaction to microgravity; growth fluids were to be injected into the seed containers after launch), as well as GPS/radar correlation tracking. The satellite included a recoverable section that was to separate on command after several weeks in orbit, fire a small internal retro-motor, and descend for recovery off the Virginia coast.[9]

The launch of Conestoga 1620 took place from a clamshell gantry, which included power and environmental control, at the south end of Wallops Flight Facility pad 0A on 23 October 1995. This pad was purpose built for the rocket.[10] The rocket launched normally, but self-destructed at 45 seconds.[8] EER determined that an unknown source of low frequency noise had caused the guidance system to order course corrections when none were needed, causing the steering mechanism to eventually run out of hydraulic fluid.

NASA had already decided to deny further funding, due to the original delays, and EER subsequently got out of the rocket business. The remaining assets were purchased by L-3 Communications in 2001 for $110 million.

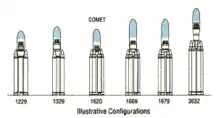

Conestoga versions

Due to the modular design of the Conestoga, a large number of configurations were possible.[7][8] The version number encoded the configuration:

- the first digit encoded the type of booster motor

- the second digit was the number of booster motors clustered around the core

- the third digit encoded the type of the first upper stage

- the fourth digit encoded the type of the second upper stage

| Version | Stages | Stage 1 | Stage 2 | Stage 3 | Stage 4 | Stage 5 | Payload (kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conestoga 1229 | 4 | 2 Castor-4B | 1 Castor-4B | Star-48V | HMACS | - | 363 kg |

| Conestoga 1379 | 4 | 3 Castor-4B | 1 Castor-4B | Star-63V | HMACS | - | 770 kg |

| Conestoga 1620 | 4 | 4 Castor-4A/B | 2 Castor-4B | 1 Castor-4B | Star-48V | - | 1179 kg |

| Conestoga 1669 | 5 | 4 Castor-4A/B | 2 Castor-4B | 1 Castor-4B | Star-63D | HMACS | 1361 kg |

| Conestoga 1679 | 5 | 4 Castor-4A/B | 2 Castor-4B | 1 Castor-4B | Star-63V | HMACS | 1497 kg |

| Conestoga 3632 | 5 | 4 Castor-4A/B-XL | 2 Castor-4B-XL | 1 Castor-4B-XL | Orion-50 | Star-48V | 2141 kg |

Launch history

| Date/Time (UTC) | Rocket | Launch site | Payload | Outcome | Apogee | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1981-08-05 | Percheron | Matagorda Island | Failure | 0 kilometres (0 mi) | Pad explosion.[1] | |

| 1982-09-09, 15:12 | Conestoga 1 | Matagorda Island | 18 kg (40 lb) water | Success | 309 kilometres (192 mi) | [11] |

| 1995-10-23, 22:03 | Conestoga 1620 | Wallops Island | Meteor recoverable experimental satellite | Failure | 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) | Hydraulic fluid depletion.[2] |

See also

References

- 1 2 Wade, Mark. "Percheron". Encyclopedia Astronautica. Archived from the original on 2014-08-05. Retrieved 2014-05-18.

- 1 2 Wade, Mark. "Conestoga 1620". Encyclopedia Astronautica. Archived from the original on 2013-12-04. Retrieved 2014-05-18.

- ↑ Woods, Michael (Sep 23, 1981). "Rocket Failure Brings Favorable Fame: Private Effort Ended In Launch Explosion". Toledo Blade. Toledo, OH. p. 1.

- ↑ Richman, Tom (Jul 1, 1982). "The Wrong Stuff". Inc.

- 1 2 "Conestoga-1". Gunter's Space Page. Retrieved 2023-11-29.

- ↑ Abell, John C. (September 9, 2009). "Sept. 9, 1982: 3-2-1 … Liftoff! The First Private Rocket Launch". Wired.

- 1 2 "Conestoga-1000". Gunter's Space Page. Retrieved 2023-09-28.

- 1 2 3 4 "Conestoga-1620". Gunter's Space Page. Retrieved 2023-09-28.

- ↑ "COMET: GATEWAY TO COMMERCIAL SPACE".

- ↑ Wade, Mark. "Wallops Island LA0A". Encyclopedia Astronautica. Archived from the original on 2008-11-20. Retrieved 2009-01-21.

- ↑ Wade, Mark. "Matagorda Island". Encyclopedia Astronautica. Archived from the original on 2014-02-10. Retrieved 2014-05-18.

- Butrica, Andrew J. (March 15, 1998). The Commercial Launch Industry, Technological Change, and Government-Industry Relations. Business History Conference. College Park, Maryland. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved January 15, 2007.

- "Today in Technology History". The Center for the Study of Technology and Society. September 9, 2002. Archived from the original on October 15, 2009.

- Harrigan, Stephen (November 1982). "Mr. Hannah's Space Venture". Texas Monthly.