Peter C. Pearson | |

|---|---|

Pearson, Uganda 1928 | |

| Born | 16 January 1877 |

| Died | 10 September 1929 |

| Other names | Pete |

| Occupation(s) | Elephant hunter & game warden |

| Years active | 1903–1929 |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | British Empire |

| Service/ | British Army |

| Years of service | c.1901–1902 (Boer War) 1914–1918 (First World War) |

| Rank | Lieutenant |

Peter C. "Pete" Pearson (16 January 1877 – 10 September 1929) was an Australian-born game ranger, poacher, and professional hunter in East Africa.

Biography

Early life

Pearson was born in Melbourne in 1877, he was educated at Caulfield Grammar School but could not settle into a life in Melbourne and at the age of 18 he left home and travelled Australia in search of adventure. In those years Pearson travelled throughout Australia extensively, working in various occupations including as a surveyor's assistant in Gippsland, a shearer in New South Wales and Queensland and a miner at Broken Hill.[1]

In order to reach the Boer War, in 1900 Pearson volunteered as an ordinary seaman on a ship to get to South Africa. Upon arrival at Durban the crew simply laughed at his request to be let ashore so he decided to swim, having swum 200 yards (180 m) he noticed a shark's fin making a beeline towards him, after some struggles he managed to clasp a piece of driftwood and paddle ashore, several sharks menacingly circling him the entire way. Upon arrival in South Africa, Pearson managed to join a cavalry regiment towards the end the war.[1][2]

Professional hunter

After the Boer War, Pearson remained in Africa, sailing to Kenya he arrived in Mombasa in 1903. A short time later he decided to hunt elephant professionally, travelling to Uganda he initially hunted in the Masindi district but the found the newly imposed game laws limiting hunters to three elephant a year too restricting to make a living.[2]

"Gentleman adventurer" of the Lado

In 1904 Pearson met the veteran elephant hunter Bill Buckley who told Pearson of the large herds of elephant that could be poached with relative impunity in the largely un-policed Lado Enclave, Pearson immediately agreed to join Buckley on an expedition there that year. Whilst his partnership with Buckley did not last beyond that first expedition, the pair saw many elephant, on morning encountering a herd they estimated to number 2,000 animals. Pearson continued to hunt solo in the Lado Enclave until 1910, when the territory returned to British rule following the death of King Leopold II of Belgium.[2][3][4]

The illegal hunters in the Lado made great use of Belgium's inadequate administration of the territory, as well as the Belgian authorities' mistreatment of the native inhabitants. Typically the hunters of the Lado earned the loyalty and friendship of the local tribesmen by offering them the meat from the elephant they killed, and in exchange the tribesmen provided warning of movements of the Belgian patrols, some essential food supplies and porters to assist in transporting the harvested ivory back to Uganda. In 1909, Theodore Roosevelt traveled to Uganda during the Smithsonian–Roosevelt African Expedition to hunt white rhinoceros, but also to meet the famed elephant hunters of the Lado. During a dinner in Koba with those hunters who were available, including Pearson, Roosevelt offered a toast "to the ivory poachers of the Lado Enclave", upon hearing the good humoured protests of some of those present, Roosevelt reworded the toast "to the company of gentlemen adventurers".[1][4][5][6][7][8]

Pearson typically organised his illegal hunting expeditions from Koba, a British administrative post on the opposite bank of the Nile from the Lado Enclave. The illegal hunters of the Lado typically earned £3,000 to £4,000 profit from a six-month poaching expedition into the territory and Pearson was considered one of the most successful of them, amassing a small fortune. Upon the imposition of British administrative rule of the Lado Enclave, Pearson recommenced licensed elephant hunting, hunting in the Belgian Congo predominantly in the Ituri forest and later in Ubangi-Shari, the authorities in Belgian and French controlled territories still issued commercial hunting licences for between 20 and 30 elephants.[2][3][4]

World War I

With the outbreak of the Great War in 1914, the British government were concerned the German authorities in German East Africa would arm local tribes and cause dissatisfaction amongst the native tribespeople. The British Army requested the services of men with extensive knowledge of the East African bush and experience in dealing with local tribesmen, Pearson readily enlisted. Pearson was given the honorary rank of Lieutenant in the East Africa Protectorate's Intelligence Department, he served out the war in this capacity.[1][9]

Post-war hunting

After World War I Pearson returned to hunting, initially in Tanganyika (the former German East Africa) where licences for up to 25 elephants could be obtained, then later when these too were outlawed, he returned to Uganda. Despite having earned a great deal of money during his time poaching in the Lado, Pearson had little experience in saving or investing money and he fell upon hard times, making a meager living from the ivory he harvested from the few licences he could obtain to shoot elephant in the British territories.[2][3]

Game warden

In an effort to combat the destruction to cropping and fencing caused by elephant that prevented the development of agriculture, in 1924 the Ugandan Government created the Uganda Game Department. The Ugandan Protectorate was divided into four large districts and a white hunter with extensive experience, along with a large native staff, was recruited as a game warden to control the elephant numbers in each district, all under the direction of chief game warden Captain C.R.S. Pitman. Pearson was recruited, along with Captain R.J.D. "Samaki" Salmon, Captain C.K.D. Palmer-Kerrison and fellow veteran of the Lado enclave F.G. "Deaf" Banks. Pearson was assigned the West Nile province which included the southern part of the old Lado Enclave, an area he knew intimately, and a salary of £50 a month, to further improve their lot in 1925 the Governor of Uganda, Sir William Gowers, made them Colonial Civil Servants by official decree, ensuring a lifetime pension.[1][2][3]

Royal guide

In 1924 Pearson, along with Samaki Salmon, accompanied the safari for the Duke and Duchess of York (later King George VI and Queen Elizabeth, The Queen Mother) as hunting guides during their visit to Uganda. In 1928 Pearson, again with Salmon, was charged with organising an 8-day hunting safari for the Prince of Wales (later King Edward VIII) during the Uganda leg of his East African royal tour. On the last day of the safari the royal party were following the tracks of a bull elephant near the Murchison Falls when they were charged by another rogue bull, Pearson grabbed the Prince and flung him to safety (into a thorn bush) then he and Salmon fired simultaneously at the elephant, which crashed dead to ground 4 yards (3.7 m) from the Prince. Sir William Gowers later wrote "it was an exhibition of presence of mind, quickness and courage which I am glad to have been privileged to witness, and which none of those who saw it will ever forget." The Prince gave Pearson a royal tie pin and cufflinks as mementoes of the occasion.[1][3][8]

Death

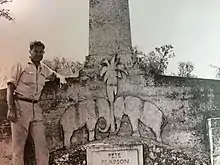

In the summer of 1929 Pearson became ill and tests revealed he had stomach cancer. Pearson had confided in Sir William Gowers that upon his death he would like a small monument to his memory in the Bakumi district on an escarpment that overlooks Lake Albert at a place beside the road between Masindi and Butiaba. It was from this spot, which offers panoramic views of the area, that Pearson used to sit and look for elephants through field glasses. After a short illness, Pearson died in the Kampala hospital on 10 September 1929, Sir William honoured Pearson's request and, upon consulting the Prince of Wales, established a fund for those who wished to contribute to Pearson's memorial, many people including the Prince of Wales contributed and the monument was erected.[1][2][3]

Description

Physique

Pearson was said to be a tall, heavily build man, standing over 6 feet (180 cm) tall, who sported an enormous moustache. Pearson, like the other hunters of Lado, was a fit man, always hunting on foot, he would walk between 20 and 30 miles (32 and 48 km) a day following a single bull elephant.[1][2]

Character

Pearson was respected and admired by his fellow hunters, but most people who knew him found him to be brusque and uncommunicative. Pearson was said to lead a spartan life, enjoying only one luxury being fine champagne, every time he returned from safari he would drink a large number of bottles.[2][3][8]

Hunting preferences and records

Pearson left no detailed accounts of his hunting career and was loath to discuss the total number of elephants he shot or the largest tusks he ever harvested. It has been estimated that over the course of his life, including his time as a poacher, legal hunter and elephant control officer, he shot as many as 2,000 elephants throughout his life, making him one of the most experienced elephant hunters of all time. Pearson shot one bull elephant in the Lado Enclave with tusks that weighed 155 and 153 pounds (70 and 69 kg) respectively, whilst Pearson told the Prince of Wales that in the Lado he shot a total of three bull elephants with tusks that weighed over 150 pounds (68 kg) each. A cow elephant Pearson shot had the heaviest tusks ever recorded for a cow, 55 and 59 pounds (25 and 27 kg) respectively, the tusks from that cow ended up in the Natural History Museum, London.[1][2][3]

Throughout the majority of his career Pearson hunted elephant with a .577 Nitro Express ejector double rifle with 24 in (61 cm) barrels, as well as a 6.5×57mm Mauser for smaller game and occasionally elephant. In later years Pearson became an enthusiast of bolt action rifles, he used a .350 Rigby, a .404 Jeffery, a .416 Rigby and a .425 Westley Richards, although his favourite was a .375 H&H Magnum he had one custom made by John Rigby & Co.[2][3][10]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Ararat Advertiser, "Pete Pearson: elephant hunter and game ranger", reprinted in 1934, retrieved from Trove 11 May 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Tony Sánchez-Ariño, Elephant hunters, men of legend, Long Beach, California: Safari Press, 2005, ISBN 978-1-57157-343-8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 David Chandler, Legends of the African frontier: the life and times of Africa's most unforgettable characters, 1800–1945, Long Beach, California: Safari Press, 2008, ISBN 1-57157-285-6.

- 1 2 3 W. Robert Foran, "Edwardian ivory poachers over the Nile", first published African affairs, Vol 57, No 227, April 1958, retrieved from rhinoresourcecenter.com, 20 September 2017.

- ↑ Craig Boddington, Elephant! The renaissance of hunting the African elephant, Long Beach, California: Safari Press, 2012, ISBN 978-1-57157-386-5.

- ↑ John Boyes, The company of adventurers, London: 'East Africa', 1928.

- ↑ East African Standard, "Obituary: Mr P.C. Pearson", Kampala, 14 September 1929.

- 1 2 3 Brian Herne, White Hunters: the golden age of African safaris, New York: Holt Paperbacks, 1999, ISBN 978-0-8050-6736-1.

- ↑ London Gazette, 8 February 1917, p 1352, retrieved from thegazette.co.uk 11 May 2018.

- ↑ John Taylor, African rifles and cartridges, Sportsman’s Vintage Press, 2013, ISBN 978-1-940001-01-2.