Peter Buell Porter (August 14, 1773 – March 20, 1844) was an American lawyer, soldier and politician who served as United States Secretary of War from 1828 to 1829.

Early life

Porter was born on August 14, 1773, one of six children born to Dr. Joshua Porter (1730–1825) and Abigail Buell (1734–1797), who married in 1759 in Lebanon, Connecticut.[1] His siblings were: Joshua Porter (1760–1831), Abigail Porter (1763–1797), Eunice Porter (1766–1848), Augustus Porter (1769–1849), Sally Porter (1776–1820).[1] His father, Dr. Joshua Porter, a 1754 graduate of Yale, fought in the Revolutionary War as a colonel. He was at the head of his regiment in October 1777 when John Burgoyne surrendered his 6,000 men after the Battles of Saratoga. After the war, he was elected to various official positions for forty-eight consecutive years.[2] His maternal grandparents were Peter and Martha Buell (née Grant) of Coventry, Connecticut.[1]

He attended and graduated from Yale College in 1791, studied law in Litchfield, Connecticut with Judge Tapping Reeve, who also taught Aaron Burr and John C. Calhoun.[3]

Career

In 1793, Porter was admitted to the bar, and commenced practice in Canandaigua, New York. From 1797 to 1804, he was Clerk of Ontario County, and was a member of the New York State Assembly (Ontario and Steuben Co.) in 1802. In the fall of 1809, Porter moved to Black Rock, New York, later part of Buffalo, and became a member of the firm of Porter, Barton & Company with his brother Augustus, which controlled transportation on the Niagara River.[3] The company portaged goods by land from Lake Erie to Lewiston on the Niagara River through Niagara Falls, then shipped them east on Lake Ontario.[4]

United States Congress

In 1809, he was elected to the United States House of Representatives as a Democratic-Republican. He served in the 11th and 12th United States Congresses, holding office from March 4, 1809, to March 3, 1813. During his service in Congress, he was a leading figure among Congressional "war hawks" and Chairman of the Committee that recommended preparation for war with Great Britain, and was known as an early supporter of James Madison.[5] Porter, along with Henry Clay and others, pressured Madison to end the discussion and take up arms against England, in what became known as the War of 1812.[5]

At the same time, from 1810 to 1816, he was a member of the Erie Canal Commission, a commission on inland navigation established in 1810 by the New York State Legislature to survey a canal route from the Hudson River to the Great Lakes.[3] Porter served on the Commission with fellow Democratic-Republicans, Simeon De Witt and DeWitt Clinton. The Federalists on the Committee were Gouverneur Morris, William North, Thomas Eddy, and Stephen Van Rensselaer. In 1811, Porter and the Democratic-Republicans were joined by Robert R. Livingston and Robert Fulton. Charles D. Cooper joined in 1815.[6][7][8]

War of 1812

While in Congress, Porter, realizing the level of America’s unpreparedness for war, pushed for greater numbers of soldiers and supplies. When his efforts fell on deaf ears, he instead offered his experience in trade to the military. Beginning in May 1812, he was served as assistant quartermaster general in the New York State Militia.[5] As a brigadier general, he criticized General Alexander Smyth’s abortive operations against British Canada in 1813 at the Battle of Frenchman's Creek , culminating in a bloodless duel between the two. The historian John R. Elting wrote of the duel, stating "Unfortunately, both missed."[9]

Porter later raised and commanded a brigade of New York militia that incorporated a Six Nations Indian contingent and led his command with distinction. He brokered a deal with Red Jacket, who agreed to provide 500 troops under Porter's command.[5] For his actions, he was presented a gold medal under joint resolution of Congress dated November 3, 1814 "for gallantry and good conduct" during the Battle of Chippewa, the Battle of Niagara, and the Siege of Fort Erie.[3]

Ambush at Black Rock

A British raiding force of 240 troops including regulars and militia led by Lt. Col. Cecile Bishop attacked Black Rock, New York. The American militia numbering 150 men guarding the location fled. The British raiders spiked guns, burned structures, destroyed a schooner, and took many provisions. While this was going on, Peter B. Porter gathered at least 140 militiamen, a company of regulars, and at least 40 allied Seneca warriors. While the British raiding force was withdrawing back to their own lines. Porter’s force ambushed them. The 40 Seneca warriors who were concealed in a ravine rose above cover and gave the war-whoop while attacking the British by surprise while Porter’s other troops attacked from 3 different points. The British were caught off guard and confused by the sudden American attack. The British withdrew in confusion to their boats returning to their lines. The British suffered 3 killed, 24 wounded, and 17 captured. One of the British killed was Lt. Col. Cecile Bishop. The American ambushing force suffered only 3 killed and 6 wounded.[10][11]

Ambush at South of Chippawa

Peter B. Porter was able to successfully negotiate an alliance with Red Jacket to assist the American armed forces in the Battle of Chippawa. Red Jacket conceived of a plan to maneuver his force of 300 Seneca warriors close enough to ambush the enemy force which consisted of British regulars, Canadian militia, and Mohawks. Peter B. Porter accompanied Red Jacket’s force with a force of his own numbering 250-300 men. Porter’s 250-300 man force consisted mostly of American militia and some U.S. regulars. Porter and Red Jacket headed with their combined force of 600 Senecas, militia, and regulars to ambush the British-allied force. Porter’s 600 man force moved stealthily into the woods, creeping off to the south. The Americans entered the natural cover of the massive forest to stay out of sight of the enemy. The Americans came close undetected to the enemy’s position. The Americans formed a formation of 3 arcs. Red Jacket’s Senecas were in the 2 front arcs while Porter’s men were in the third arc in the rear. Red Jacket’s Senecas all wore white-hankie hats so that Porter’s men could tell the difference between a British Mohawk Indian and a pro-American Seneca indian in the heat of battle. Once the Americans were in position enveloping the unsuspecting enemy. Each American aimed and leveled his gun at an enemy. The Americans sprang their ambush and opened heavy fire. The British-allied force was taken completely by surprise and many of them dropped dead. The Americans then charged in and engaged the enemy in close hand-to-hand combat. The Americans brutally killed many British, Canadian, and Mohawk as they were still so shocked and confused from the American ambush. The British and their allies retreated into the wilderness. Peter and his force pursued the enemy. However, the Americans ran into a fresh reserve of British regulars waiting in linear formation who fired a volley. Porter and his force retreated to safety as the British pursued them a short distance. After the battle of Chippawa ended between the main British army and the main American army, all British forces including the British main army withdrew temporarily. Porter and his men came back to their ambush site to police the scene to assess casualties of their force and of the enemy. There were at least 90 dead bodies of British, Canadian, and mohawks. There were only a dozen dead Americans on the field. The Senecas scalped all of the dead British, Canadian, and Mohawks. After that, Porter, Red Jacket, and their forces withdrew from the field.[12]

Battle of Lundy’s Lane

Peter Porter took part in this battle. Porter reinforced Jacob Brown’s main position with his militia. Other American forces engaged the British in ferocious fighting. After a long battle, the Americans withdrew under Jacob Brown’s orders against Porter’s advice.[13]

Hit-and-run sortie at Fort Erie

During the siege of Fort Erie, the British suffered heavy casualties after making costly infantry assaults on the American entrenched fort. The Americans who were deeply entrenched in their fort’s defenses suffered minor casualties. The American commander Jacob Brown then wanted to conduct hit-and-run sorties on the British to cause heavier casualties on the British, disable their artillery, and destroy the magazine supplies. Peter B. Porter was to conduct one sortie while James Miller was to lead the other. Peter B. Porter would lead a raiding sortie of militia and regulars while Miller would lead a raiding party of regulars. The American raiders would infiltrate British lines to conduct their mission. Porter secretly led his force traveling along a hidden road using the cover of the woods while Miller led his force secretly in a ravine. The American raiders struck by surprise and full ferocity. In the chaotic attack, the Americans destroyed 3 batteries of cannons, blew up the magazine, and inflicted heavy casualties on the British. Afterwards, all the American raiders withdrew back into the fort. The British suffered 115 killed, 178 wounded, and 316 missing. The American raiders led by Porter and Miller suffered 79 killed, 216 wounded, and 216 missing. Even though the American sorties completed their objectives, it was still costly in terms of casualties for the Americans. Some time later, the entire American force at fort erie would evacuate to Sackets Harbor.[14][15]

End of the War

With the end of military operations, Porter went to Washington where he was given command of all American forces on the Niagara Frontier by President Madison. When news of a peace treaty arrived, he returned to civilian life and was declared a hero by his fellow citizens.[16]

New York politics and return to Congress

From February 1815 to February 1816, he served as Secretary of State of New York as a Democratic-Republican under New York Governor Daniel D. Tompkins. He was also elected to the 14th United States Congress. Although his term in Congress began on March 4, 1815, the actual Session began only in December, and he took his seat on December 11, 1815. On January 23, 1816, he resigned, having been appointed a Commissioner under the Treaty of Ghent, which caused a controversy as to the constitutionality of sitting in Congress and holding this commissionership at the same time.[17]

In 1817, his political friends of Tammany Hall printed ballots with his name and distributed them among their followers to vote for Porter for Governor of New York at the special election which was held after the resignation of Governor Daniel D. Tompkins. DeWitt Clinton, the otherwise unopposed candidate, was fiercely hated by the Tammany organization, and Porter received about 1,300 votes although he was not really running for the office. Porter became a regent of the University of the State of New York in 1824, and served in that capacity until 1830.[3]

He was again a member of the State Assembly (Erie Co.) in 1828, but vacated his seat when he was appointed to the Cabinet.[3]

Secretary of War

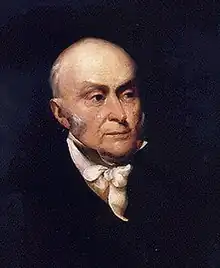

From May 16, 1828, to March 9, 1829, Porter served as U.S. Secretary of War under President John Quincy Adams, and was an advocate for the removal of Eastern Indians beyond the Mississippi. He moved to Niagara Falls in 1836 and was a presidential elector on the Whig ticket in 1840.[3]

Personal life

In 1818, Porter married Letitia Breckinridge (1786–1831), the daughter of John Breckinridge (1760–1806),[18] a U.S. Senator from Kentucky from 1801 to 1805, and Attorney General of the United States under Jefferson from 1805 to 1806.[19] Her mother was Mary Hopkins Cabell, of the Cabell political family.[18] Letitia was widowed from her first marriage in 1804, to Alfred William Grayson, who had died in 1810. Grayson, a graduate of Cambridge University, was the son of Senator William Grayson of Virginia. Through her first marriage, she had a son, John Breckinridge Grayson (1806–1862).[20] Together, Peter and Letitia had:

- Peter Augustus Porter (1827–1864), who married Mary Cabell Breckenridge (1826–1854)

- Elizabeth Lewis Porter (1828–1876), who was rumored to have almost married Millard Fillmore, who later served as President of the United States from 1850 to 1853.[21]

On March 20, 1844, General Porter died in Niagara Falls and was interred in Oakwood Cemetery, along with brother Augustus.

Descendants

.jpg.webp)

His son, Peter A. Porter died in the bloody Battle of Cold Harbor during the American Civil War. His grandson was Peter Augustus Porter (1853–1925), a U.S. Representative from New York and his nephews were Augustus Seymour Porter, a United States Senator from Michigan, and Peter B. Porter, Jr., an Assemblyman and Speaker of the New York State Assembly.

Slave Ownership

In 1820, Porter and his wife Letitia signed an affidavit attesting to the ownership of five enslaved Africans. Their names were recorded as John Caldwell, born 1800; Richard Caldwell, born 1810; Lannia Caldwell, born 1803; Mildred Caldwell, born 1806; and Betsy Gatewood, born 1815. This affidavit appears in the Buffalo Town Proceedings,[23] p.93, in the collection of the Buffalo History Museum.

Legacy

Fort Porter, Porter Avenue in Buffalo, Porter Road in Niagara Falls, and Porter Township in Niagara County are all named in honor of Gen. Porter.[24] Porter's letters and papers survive in the library collections of the Buffalo History Museum.[25]

Porter Hall at Buffalo State College was named after Gen. Porter in 1980 but changed to Bengal Hal in July 2020 due to Porter's slave ownership. [26] Similarly, Porter Quadrangle within the Ellicott Complex at the University at Buffalo was named after Porter in 1974 but his name was removed in August 2020 due to Porter's slave ownership.[27]

In 1834, a paddle steamer named the General Porter was launched, on Lake Erie.[22] She sailed out of Buffalo, New York, until 1838, when she was sold to the Royal Navy, which renamed her HMS Toronto. The Royal Navy employed her patrolling Lake Erie, the St Clair River, and the upper Niagara River.

References

- Notes

- 1 2 3 Welles, Albert (1881). History of the Buell Family in England: From the Remotest Times Ascertainable from Our Ancient Histories, and in America, from Town, Parish, Church and Family Records. Illustrated with Portraits and Coat Armorial. New York: Society Library. Retrieved October 27, 2016.

- ↑ "The Late Col. Porter. Funeral of Col. P.A. Porter Sketch of his Life and Character". The New York Times. June 18, 1864. Retrieved October 21, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Bell, William Gardner (March 1, 2001). "Peter Buell Porter". history.army.mil. Center Of Military History United States Army. Retrieved October 27, 2016.

- ↑ Foran, Jack. "The Day They Turned The Falls On: The Invention Of The Universal Electrical Power System". library.buffalo.edu. University of Buffalo. Archived from the original on September 20, 2017. Retrieved October 26, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 Ridler, Jason (2011). "War of 1812". www.eighteentwelve.ca. RCGS/HDI/Parks Canada. Archived from the original on February 6, 2017. Retrieved October 27, 2016.

- ↑ Morris, North, De Witt, Eddy, Porter and Cooper ceased to be Commissioners when the Legislature appointed a new Commission consisting of Clinton, Van Rensselaer, Ellicott, Holley and Young.

- ↑ Bernstein, Peter L. (2005)

- ↑ Koeppel, Gerard (2009)

- ↑ Elting, John R. (1991). Amateurs, to Arms! A Military History of the War of 1812. Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill. pp. 51. ISBN 0-306-80653-3.

- ↑ “Lossing's War of 1812: Lossing’s Pictorial Field Book of the War of 1812" by Benson Lossing Chapter XXVIII.

- ↑ “Harper's Magazine, Volume 27" by Making of America Project Page.608-609.

- ↑ "Dispatches from the War of 1812 "Guerrillas in a Thrilla: The Battle of Chippawa, Part 2"". History Of Buffalo. June 26, 2022. Retrieved June 26, 2022.

- ↑ “ PICTORIAL FIELD-BOOK OF THE WAR OF 1812” by BENSON J. LOSSING Chapter Chapter XXXVI.

- ↑ "The War of 1812: A Complete Chronology with Biographies of 63 General Officers" by Bud Hannings Pages.230.

- ↑ "PICTORIAL FIELD-BOOK OF THE WAR OF 1812." by BENSON J. LOSSING Chapter XXXVI.

- ↑ Grande, Dr. Joseph A.; LaChiusa, Chuck. "Peter B. Porter". www.buffaloah.com. The Courier-Express: Buffalo Architecture and History. Retrieved October 27, 2016.

- ↑ Google Books: Abridgment of the Debates of Congress, from 1789 to 1856 page 585

- 1 2 BRECKINRIDGE, John – Biographical Information. Bioguide.congress.gov. Retrieved on October 19, 2011.

- ↑ Index to Politicians: Breckinridge. The Political Graveyard. Retrieved on October 19, 2011.

- ↑ The Cabells and their kin: A ... – Alexander Brown – Internet Archive. Books.google.com (July 19, 2007). Retrieved on October 19, 2011.

- ↑ "Elizabeth Lewis Porter - Oakwood Cemetery". www.acsu.buffalo.edu. Oakwood Cemetery Inc. Retrieved October 27, 2016.

- 1 2 "GENERAL PORTER; 1834; Steamer; AMERICAN". Great Lakes Maritime Database. Archived from the original on October 6, 2014.

- ↑ "Buffalo Town Proceedings, 1814-1837". Retrieved January 4, 2024.

- ↑ "Peter B. Porter".

- ↑ "Guide to the Microfilm Edition of the Peter B. Porter Papers". Retrieved January 4, 2024.

- ↑ "Porter name coming off residence hall at Buffalo State". www.wivb.com. WIVB. July 31, 2020. Retrieved August 1, 2020.

- ↑ David J. Hill (August 3, 2020). "UB to remove names of Millard Fillmore, James O. Putnam, Peter B. Porter". www.buffalo.edu. Retrieved January 11, 2021.

Further reading

- Stagg, J. C. A. "Between Black Rock and a hard place: Peter B. Porter's plan for an American invasion of Canada in 1812." Journal of the Early Republic 19.3 (1999): 385-422. online

- Scheuer, Michael F. "Peter Buell Porter And The Development Of The Joint Commission Approach To Diplomacy In The North Atlantic Triangle." American Review of Canadian Studies 12.1 (1982): 65-73.

- Mogavero, I. Frank. "Peter B Porter, citizen and statesman" (PhD. Diss. University of Ottawa, 1950) online.

- United States Congress. "Peter Buell Porter (id: P000446)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- Biography in Secretaries of War and Secretaries of the Army a publication of the United States Army Center of Military History

- Bernstein, Peter L, Wedding of the Waters, New York: W.W. Norton and Co., 2005.

- Cornog, Evan, The Birth of Empire: DeWitt Clinton and the American Experience, 1769-1828, New York: Oxford University Press, 1998.

- Koeppel, Gerard, "Bond of Union: Building the Erie Canal and the American Empire", Cambridge, Mass.: Da Capo Press, 2009.

- Shaw, Ronald E, Erie Water West: A History of the Erie Canal, 1792-1854 Lexington, Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky, 1990.