G-YMMM after the crash at London Heathrow Airport. | |

| Accident | |

|---|---|

| Date | 17 January 2008 |

| Summary | Fuel starvation caused by ice in the fuel/oil heat exchangers, crashed short of runway |

| Site | London Heathrow Airport, United Kingdom 51°27′54″N 0°25′54″W / 51.46500°N 0.43167°W |

| Aircraft | |

| Aircraft type | Boeing 777-236ER |

| Operator | British Airways |

| IATA flight No. | BA38 |

| ICAO flight No. | BAW38 |

| Call sign | SPEEDBIRD 38 |

| Registration | G-YMMM |

| Flight origin | Beijing Capital International Airport, China |

| Destination | London Heathrow Airport, England, United Kingdom |

| Occupants | 152 |

| Passengers | 136 |

| Crew | 16 |

| Fatalities | 0 |

| Injuries | 47 (1 serious) |

| Survivors | 152 |

British Airways Flight 38 was a scheduled international passenger flight from Beijing Capital International Airport in Beijing, China, to London Heathrow Airport in London, United Kingdom, an 8,100-kilometre (4,400 nmi; 5,000 mi) trip. On 17 January 2008, the Boeing 777-200ER aircraft operating the flight crashed just short of the runway while landing at Heathrow.[1][2][3] No fatalities occurred; of the 152 people on board, 47 sustained injuries, one serious.[4] It was the first time in the aircraft type's history that a Boeing 777 was declared a hull loss, and subsequently written off.[5][6]

The accident was investigated by the Air Accidents Investigation Branch (AAIB) and a final report was issued in 2010. Ice crystals in the jet fuel were blamed as the cause of the accident, clogging the fuel/oil heat exchanger (FOHE) of each engine. This restricted fuel flow to the engines when thrust was demanded during the final approach to Heathrow.[7] The AAIB identified this rare problem as specific to Rolls-Royce Trent 800 engine FOHEs. Rolls-Royce developed a modification to the FOHE; the European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) mandated all affected aircraft to be fitted with the modification before 1 January 2011.[4][8] The US Federal Aviation Administration noted a similar incident occurring on an Airbus A330 fitted with Rolls-Royce Trent 700 engines and ordered an airworthiness directive to be issued, mandating the redesign of the FOHE in Rolls-Royce Trent 500, 700, and 800 engines.[9]

Aircraft

The aircraft involved in the accident was a Boeing 777-236ER, registration G-YMMM (manufacturer's serial number 30314, line number 342), powered by two Rolls-Royce Trent 895-17 engines.[10] The aircraft first flew on 18 May 2001 and was delivered to British Airways on 31 May 2001.[11] It had a seating capacity of 233 passengers.[4](p12) On board were 16 crew members and 136 passengers. The crew consisted of Captain Peter Burkill (43), Senior First Officer John Coward (41), First Officer Conor Magenis (35), and 13 cabin crew members. The captain had 12,700 total flight hours, with 8,450 in Boeing 777 aircraft. The senior first officer had 9,000 total flight hours, with 7,000 in Boeing 777 aircraft. The first officer had 5,000 total flight hours, with 1,120 in Boeing 777 aircraft.[4](pp7-8)

Accident

Flight 38 departed from Beijing at 02:09 Greenwich Mean Time (GMT), flying a route that crossed Mongolia, Siberia, and Scandinavia, at altitudes between flight level 348 and 400—approximately 34,800 and 40,000 feet (10,600 and 12,200 m), and in temperatures between −74 °C (−101 °F) and −65 °C (−85 °F).[4](p33-34) Aware of the cold conditions outside, the crew monitored the temperature of the fuel, with the intention of descending to a lower and warmer level if any danger of the fuel freezing arose.[4](p4) This did not prove necessary, as the fuel temperature never dropped below −34 °C (−29 °F), still well above its freezing point.[Note 1]

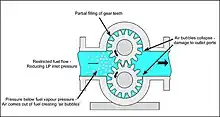

Although the fuel itself did not freeze, small quantities of water in the fuel did.[Note 2] Ice adhered to the inside of the fuel lines, probably where they ran through the pylons attaching the engines to the wings.[4](p155) This accumulation of ice had no effect on the flight until the final stages of the approach into Heathrow, when increased fuel flow and higher temperatures suddenly released it back into the fuel.[4](p155) This formed a slush of soft ice that flowed forward until it reached the fuel/oil heat exchangers (FOHEs)[Note 3] where it froze once again, causing a restriction in the flow of fuel to the engines.[4](p155)[4](p149)

The first symptoms of the fuel-flow restriction were noticed by the flight crew at an altitude of 720 feet (220 m) and 2 miles (3.2 km) from touchdown, when the engines repeatedly failed to respond to a demand for increased thrust from the autothrottle. In attempting to maintain the instrument landing system glide slope, the autopilot sacrificed speed, which reduced to 108 knots (200 km/h; 124 mph) at 200 feet (61 m).[1] The autopilot disconnected at 150 feet (46 m), as the co-pilot took manual control.[4](p139) Meanwhile, the captain reduced the flap setting from 30 to 25° to decrease the drag on the aircraft and stretch the glide.[4](p139)[13]

At 12:42, the 777 passed just above the residential street of Myrtle Avenue,[14] then immediately after overflew traffic on the A30 and the airport's Southern Perimeter road and landed on the grass about 270 metres (890 ft) short of runway 27L.[4](p5) The captain declared an emergency to air traffic control a few seconds before landing. The decision to raise the flaps allowed the plane to glide beyond the ILS beacon within the airport perimeter, thus avoiding more substantial damage.[4](p140)

During the impact and short slide over the ground, the nose gear collapsed, the right main gear separated from the aircraft, penetrating the central fuel tank and the passenger oxygen supply, causing a major fuel leak and the release of oxygen gas from adjacent compartments.[4](pp160-163) The right main landing gear also penetrated the cabin space, causing the sole serious injury in this accident to a passenger in seat 30K. The left main gear was pushed up through the wing, as it was designed to do in case of failure due to excessive vertical load. The aircraft came to rest on the threshold markings at the start of the runway. 6,750 kg (14,880 lb) of fuel leaked, but no fire started.[4](p68) One passenger received serious injuries (concussion and a broken leg), and four crew members and eight passengers received minor injuries.[1][2][3]

Aftermath

The London Ambulance Service stated that three fast response cars, nine ambulances, and several officers were sent to the scene to assess the casualties. Those injured were taken to the nearby Hillingdon Hospital.[15]

Willie Walsh, the British Airways chief executive, released a statement praising the actions of the "flight and cabin crew [who] did a magnificent job and safely evacuated all of the 136 passengers ... The captain of the aircraft is one of our most experienced and has been flying with us for nearly 20 years. Our crews are trained to deal with these situations."[16] He also praised the fire, ambulance, and police services.

All flights in and out of Heathrow were halted for a short time after the accident. When operations resumed, many long-haul outbound flights were either delayed or cancelled, and all short-haul flights were cancelled for the rest of the day. Some inbound flights were delayed, and 24 flights were diverted to Gatwick, Luton, or Stansted. In an attempt to minimise further travel disruptions, Heathrow Airport received dispensation from the Department for Transport to operate some night flights.[2] Even so, the following day (18 January), 113 short-haul flights were cancelled because crews and aircraft were out of position.[17]

On the afternoon of 20 January 2008, two cranes lifted the aircraft onto wheeled platforms and removed it from its resting place.[18] It was towed towards Heathrow's BA maintenance hangars base for storage and further inspections by the AAIB. After assessment of the damage and repair costs, the aircraft was declared to be damaged beyond economic repair (despite still being largely intact) and written off, becoming the first Boeing 777 hull loss in history.[19] It was broken up and scrapped in the spring of 2009. The dismantling and disposal was handled by Air Salvage International.[20]

During a press conference the day after the accident, Captain Peter Burkill said that he would not be publicly commenting on the cause of the incident while the AAIB investigation was in progress. He revealed that Senior First Officer John Coward was flying the aircraft, and that First Officer Conor Magenis was also present on the flight deck at the time of the accident.[21] Coward was more forthcoming in a later interview, stating: "As the final approach started I became aware that there was no power ... suddenly there was nothing from any of the engines, and the plane started to glide."[22]

Burkill and Coward were grounded for a month following the crash while they were assessed for post-traumatic stress disorder. Five months after the accident, Burkill flew again, taking charge of a flight to Montreal, Canada. He remained "haunted" by the incident, and took voluntary redundancy from British Airways in August 2009.[23] Burkill subsequently established a blog and wrote a book, Thirty Seconds to Impact, that denounced BA's treatment of the situation following the crash.[24] In November 2010, Burkill rejoined British Airways, stating, "I am delighted that the discussions with British Airways, have come to a mutually, happy conclusion. In my opinion, British Airways is the pinnacle of any pilot's career, and it is my honour and privilege to be returning to an airline that I joined as a young man."[25]

All 16 crew were awarded the BA Safety Medal for their performance during the accident. The medal is British Airways' highest honour.[26] On 11 December 2008 the crew received the President's Award from the Royal Aeronautical Society.[27]

British Airways continues to use the flight 38 designation on its Beijing to Heathrow route,[28] operating out of Beijing Daxing International Airport, usually with a Boeing 787 Dreamliner.

Initial speculations

Mechanical engine failure was not regarded as a likely cause given the very low probability of a simultaneous dual engine failure.[29] An electronic or software glitch in the computerised engine-control systems was suggested as possible causes of the simultaneous loss of power on both engines.[29] Both engine and computer problems were ruled out by the findings of the February Special Bulletin.[1]

Some speculation indicated that radio interference from Prime Minister Gordon Brown's motorcade, which was leaving Heathrow after dropping the Prime Minister off for a flight to China, was responsible for the accident. This interference was also eliminated as a cause.[4](pp145-146)

Initial analysis from David Learmount, a Flight International editor, was that "The aircraft had either a total or severe power loss and this occurred very late in the final approach because the pilot did not have time to tell air traffic control or passengers." Learmount went on to say that to land in just 350–400 metres (1,150–1,310 ft), the aircraft must have been near stalling when it touched down.[30][31] The captain also reported the aircraft's stall warning system had sounded.[32]

A METAR issued twenty minutes before the crash indicated that the wind was forecast to gust according to ICAO criteria for wind reporting.[33] The possibility of a bird strike was raised, but there were no sightings or radar reports of birds.[29] Speculation had focused on electronics and fuel supply issues.[34] A few weeks after the accident, as suspicion started to fall on the possibility of ice in the fuel, United Airlines undertook a review of their procedures for testing and draining the fuel used in their aircraft, while American Airlines considered switching to a different type of jet fuel for polar flights.[35]

Investigation

The Department for Transport's AAIB investigated the accident, with the US National Transportation Safety Board, Boeing, and Rolls-Royce also participating.[4](p1) The investigation took two years to complete, and the AAIB published its final report on 9 February 2010. Three preliminary reports and 18 safety recommendations were issued during the course of the investigation.[4](pp177-179)

The flight data recorder (FDR) and the cockpit voice recorder (CVR), along with the quick access recorder (QAR), were recovered from the aircraft within hours of the accident, and they were transported to the AAIB's Farnborough headquarters, some 30 miles (48 km) from Heathrow.[36] The information downloaded from these devices confirmed what the crew had already told the investigators, that the engines had not responded when the throttles were advanced during final approach.[37][38]

Fuel system

In its Special Bulletin of 18 February 2008, the AAIB noted evidence that cavitation had taken place in both high-pressure fuel pumps, which could be indicative of a restriction in the fuel supply or excessive aeration of the fuel, although the manufacturer assessed both pumps as still being able to deliver full fuel flow. The report noted the aircraft had flown through air that was unusually cold (but not exceptionally so), and concluded that the temperature had not been low enough to freeze the fuel. Tests were continuing in an attempt to replicate the damage seen in the fuel pumps and to match this to the data recorded on the flight. A comprehensive examination and analysis was to be conducted on the entire aircraft and engine fuel system, including modelling fuel flows, taking account of environmental and aerodynamic effects.

The AAIB issued a further bulletin on 12 May 2008, which confirmed that the investigation continued to focus on fuel delivery. It stated, "The reduction in thrust on both engines was the result of a reduced fuel flow and all engine parameters after the thrust reduction were consistent with this." The report confirmed that the fuel was of good quality and had a freezing point below the coldest temperatures encountered, appearing to rule out fuel freezing as a cause. As in the aforementioned February bulletin, the report noted cavitation damage to the high-pressure fuel pumps of both engines, indicative of abnormally low pressure at the pump inlets. After ruling out fuel freezing or contamination, the investigation then focused on what caused the low pressure at the pump inlets. "Restrictions in the fuel system between the aircraft fuel tanks and each of the engine HP pumps, resulting in reduced fuel flows, is suspected." The fuel delivery system was being investigated at Boeing, and the engines at manufacturer Rolls-Royce in Derby.

The AAIB issued an interim report on 4 September. Offering a tentative conclusion, it stated:[39]

The investigation has shown that fuel to both engines was restricted, most probably due to ice within the fuel feed system. The ice was likely to have formed from water that occurred naturally in the fuel whilst the aircraft operated for a long period, with low fuel flows, in an unusually cold environment, although, G-YMMM was operated within the certified operational envelope at all times.

The report summarised the extensive testing performed in an effort to replicate the problem suffered by G-YMMM. This included creating a mock-up of G-YMMM's fuel delivery system, to which water was added to study its freezing properties. After a battery of tests, the AAIB had not yet succeeded in reproducing the suspected icing behaviour and was undertaking further investigation. Nevertheless, the AAIB believed its testing showed that fuel flow was restricted on G-YMMM and that frozen water in the jet fuel could have caused the restriction, ruling out alternative hypotheses such as a failure of the aircraft's FADEC (computerised engine control system). The hypothesis favoured in the report was that ice had accreted somewhere downstream of the boost pumps in the wing fuel tanks and upstream of the engine-mounted fuel pumps. Either enough ice had accumulated to cause a blockage at a single point, or ice throughout the fuel lines had become dislodged as fuel flow increased during the landing approach, and the dislodged ice had then formed a blockage somewhere downstream.

Because temperatures in flight had not dropped below the 777's designed operating parameters, the AAIB recommended Boeing and Rolls-Royce take interim measures on Trent 800-powered 777s to reduce the risk of ice restricting fuel delivery.[40] Boeing did so by revising the 777 operating procedures so as to reduce the opportunities for such blockages to occur, and by changing the procedure to be followed in the event of power loss to take into account the possibility that ice accumulation was the cause.[7]

The report went on to recommend that the aviation regulators (FAA and EASA) should consider whether other aircraft types and other engines might be affected by the same problem, and to consider changing the certification process to ensure that future aircraft designs would not be susceptible to the newly recognised danger from ice formation in the fuel.[41]

The report acknowledged that a redesign of the fuel system would not be practical in the near term, and suggested two ways to lower the risk of recurrence. One was to use a fuel additive (FSII) that prevents water ice from forming down to −40 °C (−40 °F). Western air forces have used FSII for decades, and although it is not widely used in commercial aviation, it is nonetheless approved for the 777.

Rejected theories

The Special Bulletin of 18 February, stated "no evidence of a mechanical defect or ingestion of birds or ice" was found, "no evidence of fuel contamination or unusual levels of water content" was seen within the fuel, and the recorded data indicated "no anomalies in the major aircraft systems". Some small foreign bodies, however, were detected in the fuel tanks, although these were later concluded to have had no bearing on the accident.[4](p145)

The Special Bulletin of 12 May 2008 specifically ruled out certain other possible causes, stating: "There is no evidence of a wake vortex encounter, a bird strike, or core engine icing. There is no evidence of any anomalous behaviour of any of the aircraft or engine systems that suggests electromagnetic interference." [42]

Probable cause

The AAIB issued a full report on 9 February 2010. It concluded:

The investigation identified that the reduction in thrust was due to restricted fuel flow to both engines.

The investigation identified the following probable causal factors that led to the fuel flow restrictions:

- Accreted ice from within the fuel system released, causing a restriction to the engine fuel flow at the face of the FOHE, on both of the engines.

- Ice had formed within the fuel system, from water that occurred naturally in the fuel, whilst the aircraft operated with low fuel flows over a long period and the localised fuel temperatures were in an area described as the 'sticky range'.

- The FOHE, although compliant with the applicable certification requirements, was shown to be susceptible to restriction when presented with soft ice in a high concentration, with a fuel temperature that is below −10 °C and a fuel flow above flight idle.

- Certification requirements, with which the aircraft and engine fuel systems had to comply, did not take account of this phenomenon as the risk was unrecognised at that time.

Other findings

The AAIB also studied the crashworthiness of the aircraft during the accident sequence. It observed that the main attachment point for the main landing gear was the rear spar of the aircraft's wing; because this spar also formed the rear wall of the main fuel tanks, the crash landing caused the tanks to rupture. The report recommended that Boeing redesign the landing gear attachment to reduce the likelihood of fuel loss in similar circumstances.

The report went on to note that the fire extinguisher handles had been manually deployed by the crew before the fuel shut-off switches. The fire extinguisher handles also have the effect of cutting off power to the fuel switches, meaning that the fuel may continue to flow – a potentially dangerous situation. The report restated a previous Boeing Service Bulletin giving procedural advice that fuel switches should be operated before fire handles. It went on: "This was not causal to the accident, but could have had serious consequences in the event of a fire during the evacuation." Indeed, the need to issue Safety Recommendation 2008–2009, affecting all 777 airframes, which had yet to incorporate the Boeing Service Bulletin (SB 777-28-0025) – as was the case with G-YMMM – was given as the main reason for issuing the first special bulletin, well before the accident investigation itself was complete.[1]

Similar incidents

.jpg.webp)

On 26 November 2008, Delta Air Lines Flight 18 from Shanghai to Atlanta, another Trent 800-powered Boeing 777, experienced an "uncommanded rollback" of one engine while in cruise at 39,000 feet (12,000 m). The crew followed manual recovery procedures and the flight continued without incident. The US NTSB assigned one of the investigators who worked on the BA Flight 38 investigation to this incident, and looked specifically for any similarity between the two incidents.[43] The NTSB Safety Recommendation report[44] concluded that ice clogging the FOHE was the likely cause. The evidence was stronger in this case since data from the flight data recorder allowed the investigators to locate where the fuel flow was restricted.

In early 2009, Boeing sent an update to aircraft operators, linking the British Airways and Delta Air Lines "uncommanded rollback" incidents, and identifying the problem as specific to the Rolls-Royce engine FOHEs.[8] Originally, other aircraft were thought to be unaffected by the problem.[8] However, in May 2009, another similar incident happened with an Airbus A330 powered by a Trent series 700 engine.[45]

The enquiries led Boeing to reduce the recommended time that the fuel on 777 aircraft equipped with Rolls-Royce Trent 800-series engines be allowed to remain at temperatures below −10 °C (14 °F) from three to two hours.[46]

On 11 March 2009, the NTSB issued urgent safety recommendation SB-09-11 calling for the redesign of the FOHEs used on Rolls-Royce Trent 800 Series engines. A build-up of ice from water naturally occurring in the fuel had caused a restriction of the flow of fuel to the engines of G-YMMM. Rolls-Royce had already started on redesigning the component, with an in-service date of March 2010 at the latest. All affected engines were to be fitted with the redesigned component within six months of its certification.[47] In May 2010 the Airworthiness Directive was extended to cover the Trent 500 and 700 series engines, as well.[45]

Lawsuit

In November 2009, 10 passengers were announced to be suing Boeing over the incident in the Circuit Court of Cook County in Illinois, United States.[48] Each of the ten plaintiffs reportedly could receive up to US$1,000,000 (about £600,000 at the time) compensation. The lawsuit alleged that the design of the aircraft was "defective and unreasonably dangerous", that Boeing "breached their duty of care", and also breached their "warranties of merchantability and fitness".[49] Claims were settled out of court in 2012.[50]

In popular culture

The Discovery Channel Canada / National Geographic TV series Mayday featured the incident in a season-10 episode titled "The Heathrow Enigma".[51]

See also

- Aviation safety

- Cathay Pacific Flight 780, an Airbus A330 that lost engine control shortly before landing at Hong Kong International Airport in 2010

- British Airways Flight 9, a Boeing 747 that lost all engine control.

- List of accidents and incidents involving commercial aircraft

- Runway safety area

Notes

- ↑ The specification for Jet A-1 fuel requires a maximum freezing point of −47 °C (−53 °F). Depending on its exact composition, the actual freezing point can be lower than this. Subsequent testing found that the fuel on board G-YMMM had a freezing point of −57 °C (−71 °F).[4](pp117-118)

- ↑ Jet fuel contains water, as a contaminant, in concentrations of up to 100 parts per million.[12]

- ↑ The FOHE – one per engine – consists of 1,180 small-diameter steel tubes. The fuel flows through the tubes while the hot engine oil circulates around the outside. It is designed to provide two benefits: it warms the fuel to prevent ice reaching other engine components and simultaneously cools the engine oil.[4](p19)

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 "AAIB Bulletin S1/2008 SPECIAL" (PDF). AAIB. 18 February 2008. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 June 2012. Retrieved 18 February 2008. ()

- 1 2 3 "Airliner crash-lands at Heathrow". BBC. 17 January 2008. Retrieved 17 January 2008.

- 1 2 Henry, Emma; Britten, Nick (17 January 2008). "Heathrow plane crash pilot 'lost all power'". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 22 April 2008. Retrieved 26 March 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 "Report on the accident to Boeing 777-236ER, G-YMMM, at London Heathrow Airport on 17 January 2008". AAIB. Retrieved 9 February 2010.

- ↑ "Profile: Boeing 777". BBC News. 17 January 2008. Retrieved 17 January 2008.

- ↑ "Accident to Boeing 777-236, G-YMMM at London Heathrow Airport on 17 January 2008 – Initial Report Update". AAIB. 24 January 2008. Retrieved 24 January 2008.

- 1 2 3 "Safety Recommendation A-09-17 and −18" (PDF). National Transportation Safety Board. 11 March 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 October 2011.

- 1 2 3 Croft, John. "Boeing links Heathrow, Atlanta Trent 895 engine rollbacks". Flight Global. Archived from the original on 7 February 2009. Retrieved 3 February 2009.

- ↑ "Airworthiness Directives; Rolls-Royce plc RB211-Trent 500, 700, and 800 Series Turbofan Engines" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 October 2015.

- ↑ "Accident description". Aviation-safety.net. 9 February 2010. Retrieved 19 January 2011.

- ↑ "G-YMMM British Airways Boeing 777-236(ER) - cn 30314 / ln 342 - Planespotters.net Just Aviation". Archived from the original on 2 August 2010.

- ↑ "A-09-17-18" (PDF). Retrieved 6 July 2013.

- ↑ "BA crash inquiry reveals heroics". BBC. 20 May 2008. Retrieved 20 May 2008.

- ↑ Newell, Mike (3 February 2019). "Life in the shadow of Heathrow Airport". Medium. Retrieved 29 December 2023.

- ↑ "News Release – Call to Heathrow Airport" (Press release). Archived from the original on 25 September 2008.

- ↑ "Passengers survive as British Airways jet crash lands at Heathrow". The Scotsman. 17 January 2008.

- ↑ "Latest on Heathrow travel problems". BBC. 18 January 2008. Retrieved 18 January 2008.

- ↑ "Crashed jet removed from runway". BBC News. 20 January 2008. Retrieved 20 January 2008.

- ↑ "BA to write off crashed 777". FlightGlobal. 20 February 2008. Retrieved 20 January 2008.

- ↑ "What happens to a plane wreck?". bbc.co.uk. 13 June 2018. Retrieved 13 June 2018.

- ↑ "In full: BA crash pilot statement". BBC News. 18 January 2008. Retrieved 19 January 2008.

- ↑ "Heathrow crash co-pilot John Coward: I thought we'd die". Sunday Mirror. 20 January 2008. Archived from the original on 30 January 2009. Retrieved 19 January 2011.

- ↑ Booth, Jenny (9 February 2010). "Pilot of BA jet said goodbye to wife in final moments of Heathrow crash". The Times. London. Archived from the original on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

- ↑ "Air crash: '30 seconds to impact'". BBC Local (Hereford & Worcester). 24 March 2010. Retrieved 9 November 2011.

- ↑ Kaminski-Morrow, David. "British Airways to rehire captain of crashed 777". Flight International. Archived from the original on 1 October 2010. Retrieved 29 September 2010.

- ↑ "Exceptional honour for BA38 crew". Boarding, Norway. 18 July 2008. Archived from the original on 15 February 2012. Retrieved 10 December 2008.

- ↑ "RAeS MEDAL WINNERS" (PDF). Royal Aeronautical Society. Retrieved 11 February 2010.

- ↑ "Flight Aware Live Flight Tracking". Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- 1 2 3 Woods, Richard; Swinford, Steven; Eddy, Paul (20 January 2008). "Hunt for fatal flaw of Flight 38". The Times. London. Retrieved 26 March 2010.

- ↑ David Learmount (17 January 2008). "VIDEO & GRAPHIC: Flight's safety editor David Learmount gives his account of what happened to the BA Boeing 777 that crash landed at Heathrow". Flightglobal. Archived from the original on 20 May 2011. Retrieved 10 January 2012.

- ↑ David Learmount (21 January 2008). "British Airways 777 crash landing at Heathrow". Flightglobal. Retrieved 10 January 2012.

- ↑ "Heathrow Airport Crash investigation – Pilot talks". BBC News. 9 February 2010. Archived from the original on 21 December 2021. Retrieved 8 April 2012 – via YouTube.

- ↑ EGLL 171220Z 21014KT 180V240 9999 SCT008 BKN010 09/08 Q0997 TEMPO 21018G28KT 4000 RADZ BKN008 – translation here, issued by BAA Heathrow Wunderground.com

- ↑ "Leaked Detailed BA 777 Accident Investigation Update". Flight International. 1 February 2008. Archived from the original on 6 April 2013. Retrieved 1 February 2008.

- ↑ "United, American Plan Safety Push After Icing Linked to British Crash". The Wall Street Journal. 12 February 2008. Archived from the original on 17 February 2008. Retrieved 13 February 2008.

- ↑ "Accident to Boeing 777-236, G-YMMM at London Heathrow Airport on 17 January 2008 – Initial Report". AAIB. 18 January 2008. Archived from the original on 21 January 2008. Retrieved 11 August 2013.

The CVR and FDR have been successfully downloaded at the AAIB laboratories at Farnborough and both records cover the critical final stages of the flight. The QAR was downloaded with the assistance of British Airways and the equipment manufacturer.

- ↑

"Accident to Boeing 777-236, G-YMMM at London Heathrow Airport on 17 January 2008 – Initial Report". AAIB. 18 January 2008. Archived from the original on 21 January 2008. Retrieved 18 January 2008.

Initial indications from the interviews and Flight Recorder analyses show the flight and approach to have progressed normally until the aircraft was established on late finals for Runway 27L. At approximately 600 ft and 2 miles from touch down, the Autothrottle demanded an increase in thrust from the two engines but the engines did not respond. Following further demands for increased thrust from the Autothrottle, and subsequently, the flight crew moving the throttle levers, the engines similarly failed to respond. The aircraft speed reduced and the aircraft descended onto the grass short of the paved runway surface.

- ↑ "Accident to Boeing 777-236, G-YMMM at London Heathrow Airport on 17 January 2008 – Initial Report Update". AAIB. 24 January 2008. Retrieved 18 January 2008.

As previously reported, whilst the aircraft was stabilised on an ILS approach with the autopilot engaged, the autothrust system commanded an increase in thrust from both engines. The engines both initially responded, but after about 3 seconds, the thrust of the right engine reduced. Some eight seconds later the thrust reduced on the left engine to a similar level. The engines did not shut down and both engines continued to produce thrust at an engine speed above flight idle, but less than the commanded thrust.

Recorded data indicate that an adequate fuel quantity was on board the aircraft and that the autothrottle and engine control commands were performing as expected prior to, and after, the reduction in thrust.

All possible scenarios that could explain the thrust reduction and continued lack of response of the engines to throttle lever inputs are being examined, in close co-operation with Boeing, Rolls-Royce, and British Airways. This work includes a detailed analysis and examination of the complete fuel flow path from the aircraft tanks to the engine fuel nozzles. - ↑ "Interim Report – Boeing 777-236ER, G-YMMM". AAIB. 4 September 2008. Archived from the original on 12 October 2008.

- ↑ "Interim Report – Boeing 777-236ER, G-YMMM". AAIB. 4 September 2008. Archived from the original on 12 October 2008.

Safety Recommendation 2008-047: It is recommended that the Federal Aviation Administration and the European Aviation Safety Agency, in conjunction with Boeing and Rolls-Royce, introduce interim measures for the Boeing 777, powered by Trent 800 engines, to reduce the risk of ice formed from water in aviation turbine fuel causing a restriction in the fuel feed system.

- ↑ "Interim Report – Boeing 777-236ER, G-YMMM". AAIB. 4 September 2008. Archived from the original on 12 October 2008.

Safety Recommendation 2008-048: It is recommended that the Federal Aviation Administration and the European Aviation Safety Agency should take immediate action to consider the implications of the findings of this investigation on other certificated airframe/engine combinations.

Safety Recommendation 2008-049: It is recommended that the Federal Aviation Administration and the European Aviation Agency review the current certification requirements to ensure that aircraft and engine fuel systems are tolerant to the potential build-up and sudden release of ice in the fuel feed system. - ↑ AAIB Bulletin S3/2008 Special, AAIB, 12 May 2008, archived from the original on 18 August 2008

- ↑ Croft, John (10 December 2008). "NTSB investigates Heathrow-like Trent 800 engine issue". Flightglobal. Archived from the original on 25 December 2010. Retrieved 10 December 2008.

- ↑ Rosenker, Mark V. (11 March 2009). "NTSB Safety Recommendation Number A-09-19-20" (PDF). U.S. NTSB. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- 1 2 "Airworthiness Directives; Rolls-Royce plc RB211-Trent 500, 700, and 800 Series Turbofan Engines" (PDF). Federal Aviation Administration. 29 March 2010. p. 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 October 2015.

- ↑ "Boeing warns of ice problem in some 777 engines". Wings Magazine. Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 17 November 2010.

- ↑ "NTSB Issues Urgent Safety Recommendation to Address Engine Thrust Rollback Events on B-777 Aircraft" (Press release). NTSB. 11 March 2009. Retrieved 13 March 2009.

- ↑ "Heathrow crash passengers to sue". BBC News. 19 November 2009. Retrieved 7 January 2010.

- ↑ Beckford, Martin (19 November 2009). "Heathrow plane crash survivors fight for £1million damages from Boeing in landmark case". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 20 November 2009.

- ↑ Millward, David (3 October 2012). "Out of court settlement reached between British Airways passengers and manufacturers". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 13 July 2013.

- ↑ "The Heathrow Enigma". Mayday. Season 10. 2011. Discovery Channel Canada / National Geographic Channel.

External links

| External videos | |

|---|---|

![]() Media related to British Airways Flight BA38 at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to British Airways Flight BA38 at Wikimedia Commons

- Air Accidents Investigation Branch Report on the accident to Boeing 777-236ER, G-YMMM, at London Heathrow Airport on 17 January 2008

- "In Pictures: Heathrow crash-landing". BBC News. BBC. 17 January 2008.

- "Eyewitnesses on Heathrow incident". BBC News. BBC. 17 January 2008.

- "Plane passengers 'touched by God'". BBC News. BBC. 18 January 2008.

- Charig, Francis (8 February 2008). "My escape from BA038 was damn fun". The Daily Telegraph. London.

- Milmo, Dan (19 January 2008). "Safety fears over crash jet's alarm failure". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 21 January 2008.

- Accident description at the Aviation Safety Network

- Audio interviews with Capt Peter Burkill on avweb.com: Part 1 (The Crash) and Part 2 (The Aftermath)

- August 2010 edition of Flaps Podcast: Interview with Captain Burkill, where he recounted his experience and its aftermath