In classical rhetoric and logic, begging the question or assuming the conclusion (Latin: petītiō principiī) is an informal fallacy that occurs when an argument's premises assume the truth of the conclusion. Historically, begging the question refers to a fault in a dialectical argument in which the speaker assumes some premise that has not been demonstrated to be true. In modern usage, it has come to refer to an argument in which the premises assume the conclusion without supporting it. This makes it more or less synonymous with circular reasoning.[1][2]

Some examples are:

People have known for thousands of years that the earth is round. Therefore, the earth is round.

Coca Cola is the most popular soft drink in the world. Therefore, no other soft drink is as popular as Coca Cola.

God possesses all the virtues. Benevolence is a virtue. Therefore, God is benevolent.[3]

Informal use of the phrase "begs the question" also occurs with an entirely dissimilar sense in place of "prompts a question" or "raises a question".[4]

History

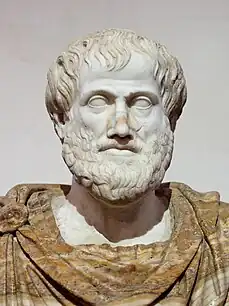

The original phrase used by Aristotle from which begging the question descends is τὸ ἐξ ἀρχῆς αἰτεῖν, or sometimes ἐν ἀρχῇ αἰτεῖν, 'asking for the initial thing'. Aristotle's intended meaning is closely tied to the type of dialectical argument he discusses in his Topics, book VIII: a formalized debate in which the defending party asserts a thesis that the attacking party must attempt to refute by asking yes-or-no questions and deducing some inconsistency between the responses and the original thesis.

In this stylized form of debate, the proposition that the answerer undertakes to defend is called 'the initial thing' (Ancient Greek: τὸ ἐξ ἀρχῆς, τὸ ἐν ἀρχῇ) and one of the rules of the debate is that the questioner cannot simply ask (beg) for it (that would be trivial and uninteresting). Aristotle discusses this in Sophistical Refutations and in Prior Analytics book II, (64b, 34–65a 9, for circular reasoning see 57b, 18–59b, 1).

The stylized dialectical exchanges Aristotle discusses in the Topics included rules for scoring the debate, and one important issue was precisely the matter of asking for the initial thing—which included not just making the actual thesis adopted by the answerer into a question, but also making a question out of a sentence that was too close to that thesis (for example, PA II 16).

The term was translated into English from Latin in the 16th century. The Latin version, petitio principii 'asking for the starting point', can be interpreted in different ways. Petitio (from peto), in the post-classical context in which the phrase arose, means 'assuming' or 'postulating', but in the older classical sense means 'petition', 'request' or 'beseeching'.[5][6] Principii, genitive of principium, means 'beginning', 'basis' or 'premise' (of an argument). Literally petitio principii means 'assuming the premise' or 'assuming the original point'.

The Latin phrase comes from the Greek τὸ ἐν ἀρχῇ αἰτεῖσθαι (tò en archêi aiteîsthai 'asking the original point')[7] in Aristotle's Prior Analytics II xvi 64b28–65a26:

Begging or assuming the point at issue consists (to take the expression in its widest sense) [in] failing to demonstrate the required proposition. But there are several other ways in which this may happen; for example, if the argument has not taken syllogistic form at all, he may argue from premises which are less known or equally unknown, or he may establish the antecedent utilizing its consequents; for demonstration proceeds from what is more certain and is prior. Now begging the question is none of these. [...] If, however, the relation of B to C is such that they are identical, or that they are clearly convertible, or that one applies to the other, then he is begging the point at issue. ... [B]egging the question is proving what is not self-evidently employing itself ... either because identical predicates belong to the same subject, or because the same predicate belongs to identical subjects.

— Aristotle, Hugh Tredennick (trans.) Prior Analytics

Aristotle's distinction between apodictic science and other forms of nondemonstrative knowledge rests on an epistemology and metaphysics wherein appropriate first principles become apparent to the trained dialectician:

Aristotle's advice in S.E. 27 for resolving fallacies of Begging the Question is brief. If one realizes that one is being asked to concede the original point, one should refuse to do so, even if the point being asked is a reputable belief. On the other hand, if one fails to realize that one has conceded the point at issue and the questioner uses the concession to produce the apparent refutation, then one should turn the tables on the sophistical opponent by oneself pointing out the fallacy committed. In dialectical exchange, it is a worse mistake to be caught asking for the original point than to have inadvertently granted such a request. The answerer in such a position has failed to detect when different utterances mean the same thing. The questioner, if he did not realize he was asking the original point, has committed the same error. But if he has knowingly asked for the original point, then he reveals himself to be ontologically confused: he has mistaken what is non-self-explanatory (known through other things) to be something self-explanatory (known through itself). In pointing this out to the false reasoner, one is not just pointing out a tactical psychological misjudgment by the questioner. It is not simply that the questioner falsely thought that the original point is placed under the guise of a semantic equivalent, or a logical equivalent, or a covering universal, or divided up into exhaustive parts, would be more persuasive to the answerer. Rather, the questioner falsely thought that a non-self-explanatory fact about the world was an explanatory first principle. For Aristotle, that certain facts are self-explanatory while others are not is not a reflection solely of the cognitive abilities of humans. It is primarily a reflection of the structure of noncognitive reality. In short, a successful resolution of such a fallacy requires a firm grasp of the correct explanatory powers of things. Without a knowledge of which things are self-explanatory and which are not the reasoner is liable to find a question-begging argument persuasive.[7]

— Scott Gregory Schreiber, Aristotle on False Reasoning: Language and the World in the Sophistical Refutations

Thomas Fowler believed that petitio principii would be more properly called petitio quæsiti, which is literally 'begging the question'.[8]

Definition

To 'beg the question' (also called petitio principii) is to attempt to support a claim with a premise that itself restates or presupposes the claim.[9] It is an attempt to prove a proposition while simultaneously taking the proposition for granted.

When the fallacy involves only a single variable, it is sometimes called a hysteron proteron[10][11][12] (Greek for 'later earlier'), a rhetorical device, as in the statement:

Reading this sentence, the only thing one can learn is a new word in a more classical style (soporific), for referring to a more common action (induces sleep), but it does not explain why it causes that effect. A sentence attempting to explain why opium induces sleep, or the same, why opium has soporific quality, would be the following one:

Opium induces sleep because it contains Morphine-6-glucuronide, which inhibits the brain's receptors for pain, causing a pleasurable sensation that eventually induces sleep.

A less obvious example from Fallacies and Pitfalls of Language: The Language Trap by S. Morris Engel:

Free trade will be good for this country. The reason is patently clear. Isn't it obvious that unrestricted commercial relations will bestow on all sections of this nation the benefits which result when there is an unimpeded flow of goods between countries?[14]

This form of the fallacy may not be immediately obvious. Linguistic variations in syntax, sentence structure, and the literary device may conceal it, as may other factors involved in an argument's delivery. It may take the form of an unstated premise which is essential but not identical to the conclusion, or is "controversial or questionable for the same reasons that typically might lead someone to question the conclusion":[15]

... [S]eldom is anyone going to simply place the conclusion word-for-word into the premises ... Rather, an arguer might use phraseology that conceals the fact that the conclusion is masquerading as a premise. The conclusion is rephrased to look different and is then placed in the premises.

— Paul Herrick[2]

For example, one can obscure the fallacy by first making a statement in concrete terms, then attempting to pass off an identical statement, delivered in abstract terms, as evidence for the original.[13] One could also "bring forth a proposition expressed in words of Saxon origin, and give as a reason for it the very same proposition stated in words of Norman origin",[16] as here:

To allow every man an unbounded freedom of speech must always be, on the whole, advantageous to the State, for it is highly conducive to the interests of the community that each individual should enjoy a liberty perfectly unlimited of expressing his sentiments."[17]

When the fallacy of begging the question is committed in more than one step, some authors dub it circulus in probando 'reasoning in a circle',[10][18] or more commonly, circular reasoning.

Begging the question is not considered a formal fallacy (an argument that is defective because it uses an incorrect deductive step). Rather, it is a type of informal fallacy that is logically valid but unpersuasive, in that it fails to prove anything other than what is already assumed.[19][20][21]

Related fallacies

Closely connected with begging the question is the fallacy of circular reasoning (circulus in probando), a fallacy in which the reasoner begins with the conclusion.[22] The individual components of a circular argument can be logically valid because if the premises are true, the conclusion must be true, and does not lack relevance. However, circular reasoning is not persuasive because a listener who doubts the conclusion also doubts the premise that leads to it.[23]

Begging the question is similar to the complex question (also known as trick question or fallacy of many questions): a question that, to be valid, requires the truth of another question that has not been established. For example, "Which color dress is Mary wearing?" may be fallacious because it presupposes that Mary is wearing a dress. Unless it has previously been established that her outfit is a dress, the question is fallacious because she could be wearing pants instead.[24][25]

Another related fallacy is ignoratio elenchi or irrelevant conclusion: an argument that fails to address the issue in question, but appears to do so. An example might be a situation where A and B are debating whether the law permits A to do something. If A attempts to support his position with an argument that the law ought to allow him to do the thing in question, then he is guilty of ignoratio elenchi.[26]

Vernacular

In vernacular English,[27][28][29][30] begging the question (or equivalent rephrasing thereof) often occurs in place of "raises the question", "invites the question", "suggests the question", "leaves unanswered the question" etc. Such preface is then followed with the question, as in:[31][32]

- "[...] personal letter delivery is at an all-time low ... Which begs the question: are open letters the only kind the future will know?"[32]

- "Hopewell's success begs the question: why aren't more companies doing the same?"[33]

- "Spending the summer traveling around India is a great idea, but it does beg the question of how we can afford it."[34]

Sometimes it is further confused with "dodging the question", an attempt to avoid it, or perhaps more often begging the question is simply used to mean leaving the question unanswered.[5]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Palmer, Humphrey (July 1981). "Do Circular Arguments Beg the Question?". Philosophy. 56 (217): 387–394. doi:10.1017/S0031819100050348. ISSN 1469-817X.

- 1 2 Herrick (2000) 248.

- ↑ Walton, Douglas (2008). Informal Logic: A Pragmatic Approach. Cambridge University Press. p. 64ff. ISBN 978-0-521-88617-8.

- ↑ Marsh, David. "Begging the question". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 March 2023.

- 1 2 Liberman, Mark (29 April 2010). "'Begging the question': we have answers". Language Log. Retrieved 12 January 2012.

- ↑ Kretzmann, N.; Stump, E. (1988). Logic and the Philosophy of Language. The Cambridge Translations of Medieval Philosophical Texts. Vol. 1. Cambridge University Press. p. 374. ISBN 978-0521280631. LCCN 87030542.

One sort of petitio is common, and another is dialectical; but common petitio is not relevant here. A dialectical petitio is an expression that insists that in the disputation some act must be performed with regard to the statable thing [at issue]. For example, "I require (peto) you to respond affirmatively to 'God exists,'" and the like. And petitio obligates [the respondent] to perform an action with regard to the obligatum, while positio obligates [him] only to maintain [the obligatum]; and in this way petitio and positio differ.

- 1 2 Schreiber, S.G. (2003). Aristotle on False Reasoning: Language and the World in the Sophistical Refutations. SUNY Series in Ancient Greek Philosophy. State University of New York Press. pp. 99, 106, 214. ISBN 978-0791456590. LCCN 2002030968.

It hardly needs pointing out that such circular arguments are logically unassailable. The importance of the Prior Analytics introduction to the fallacy is that it places the error in a thoroughly epistemic context. For Aristotle, some reasoning of the form "p because p" is acceptable, namely, in cases where p is self-justifying. In other cases, the same (logical) reasoning commits the error of Begging the Question. Distinguishing self-evident from non-self-evident claims is a notorious crux in the history of philosophy. Aristotle's antidote to the subjectivism that threatens always to debilitate such decisions is his belief in a natural order of epistemic justification and the recognition that it takes special (dialectical) training to make that natural order also known to us.

- ↑ Fowler, Thomas (1887). The Elements of Deductive Logic, Ninth Edition (p. 145). Oxford, England: Clarendon Press.

- ↑ Welton (1905), 279., "Petitio principii is, therefore, committed when a proposition which requires proof is assumed without proof."

- 1 2 Davies (1915), 572.

- ↑ Welton (1905), 280–282.

- ↑ In Molière's Le Malade imaginaire, a quack "answers" the question of "Why does opium cause sleep?" with "Because of its soporific power." In the original: Mihi a docto doctore / Demandatur causam et rationem quare / Opium facit dormire. / A quoi respondeo, / Quia est in eo / Vertus dormitiva, / Cujus est natura / Sensus assoupire. Le Malade imaginaire in French Wikisource

- 1 2 Welton (1905), 281.

- ↑ Engel, S. Morris (1994). Fallacies and pitfalls of language : the language trap. S. Morris Engel. New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-28274-0. OCLC 30671266.

- ↑ Kahane and Cavender (2005), 60.

- ↑ Gibson (1908), 291.

- ↑ Richard Whately, Elements of Logic (1826) quoted in Gibson (1908), 291.

- ↑ Bradley Dowden, "Fallacies" in Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ↑ "Fallacy". Encyclopædia Britannica.

Strictly speaking, petitio principii is not a fallacy of reasoning but an ineptitude in argumentation: thus the argument from p as a premise to p as conclusion is not deductively invalid but lacks any power of conviction since no one who questioned the conclusion could concede the premise.

- ↑ Walton, Douglas (1992). Plausible argument in everyday conversation. SUNY Press. pp. 206–207. ISBN 978-0791411575.

Wellington is in New Zealand. Therefore, Wellington is in New Zealand.

- ↑ The reason petitio principii is considered a fallacy is not that the inference is invalid (because any statement is indeed equivalent to itself), but that the argument can be deceptive. A statement cannot prove itself. A premiss [sic] must have a different source of reason, ground or evidence for its truth from that of the conclusion: Lander University, "Petitio Principii".

- ↑ Dowden, Bradley (27 March 2003). "Fallacies". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 5 April 2012.

- ↑ Nolt, John Eric; Rohatyn, Dennis; Varzi, Achille (1998). Schaum's Outline of Theory and Problems of Logic. McGraw-Hill Professional. p. 205. ISBN 978-0070466494.

- ↑ Meyer, M. (1988). Questions and Questioning. Foundations of Communication. W. de Gruyter. pp. 198–199. ISBN 978-3110106800. LCCN lc88025603.

- ↑ Walton, D.N. (1989). Informal Logic: A Handbook for Critical Argument. Cambridge University Press. pp. 36–37. ISBN 978-0521379250. LCCN 88030762.

- ↑ H.W. Fowler, A Dictionary of Modern English Usage. Entry for ignoratio elenchi.

- ↑ Garner, B.A. (1995). Dictionary of Modern Legal Usage. Oxford Dictionary of Modern Legal Usage. Oxford University Press. p. 101. ISBN 978-0195142365. LCCN 95003863.

begging the question does not mean "evading the issue" or "inviting the obvious questions," as some mistakenly believe. The proper meaning of begging the question is "basing a conclusion on an assumption that is as much in need of proof or demonstration as the conclusion itself." The formal name for this logical fallacy is petitio principii. Following are two classic examples: "Reasonable men are those who think and reason intelligently." Patterson v. Nutter, 7 A. 273, 275 (Me. 1886). (This statement begs the question, "What does it mean to think and reason intelligently?")/ "Life begins at conception! [Fn.: 'Conception is defined as the beginning of life.']" Davis v. Davis, unreported opinion (Cir. Tenn. Eq. 1989). (The "proof"—or the definition—is circular.)

- ↑ Houghton Mifflin Company (2005). The American Heritage Guide to Contemporary Usage and Style. p. 56. ISBN 978-0618604999. LCCN 2005016513.

Sorting out exactly what beg the question means, however, is not always easy—especially in constructions such as beg the question of whether and beg the question of how, where the door is opened to more than one question. [...] But we can easily substitute evade the question or even raise the question, and the sentence will be clear, even though it violates the traditional usage rule.

- ↑ Brians, Common Errors in English Usage: Online Edition (full text of book: 2nd Edition, November 2008, William, James & Company) (accessed 1 July 2011)

- ↑ Follett (1966), 228; Kilpatrick (1997); Martin (2002), 71; Safire (1998).

- ↑ Corbett, Philip B. (25 September 2008). "Begging the Question, Again". New York Times.

- 1 2 "Beg the Question". Retrieved 3 November 2018.

- ↑ "beg the question". Collins Cobuild Advanced English Dictionary online, accessed on 2019-05-13

- ↑ "beg the question" Cambridge Advanced Learner's Dictionary & Thesaurus online, accessed on 2019-05-13

References

- Cohen, Morris Raphael, Ernest Nagel, and John Corcoran. An Introduction to Logic. Hackett Publishing, 1993. ISBN 0-87220-144-9.

- Davies, Arthur Ernest. A Text-book of Logic. R.G. Adams and Company, 1915.

- Follett, Wilson. Modern American Usage: A Guide. Macmillan, 1966. ISBN 0-8090-0139-X.

- Gibson, William Ralph Boyce, and Augusta Klein. The Problem of Logic. A. and C. Black, 1908.

- Herrick, Paul. The Many Worlds of Logic. Oxford University Press, 2000. ISBN 0-19-515503-3

- Kahane, Howard, and Nancy Cavender. Logic and contemporary rhetoric: the use of reason in everyday life. Cengage Learning, 2005. ISBN 0-534-62604-1.

- Kilpatrick, James. "Begging Question Assumes Proof of an Unproved Proposition". Rocky Mountain News (CO) 6 April 1997. Accessed through Access World News on 3 June 2009.

- Martin, Robert M. There Are Two Errors in the the Title of This Book: A sourcebook of philosophical puzzles, paradoxes, and problems. Broadview Press, 2002. ISBN 1-55111-493-3.

- Mercier, Charles Arthur. A New Logic. Open Court Publishing Company, 1912.

- Mill, John Stuart. A system of logic, ratiocinative and inductive: being a connected view of the principles of evidence, and the methods of scientific investigation. J.W. Parker, 1851.

- Safire, William. "On Language: Take my question please!". The New York Times 26 July 1998. Accessed 3 June 2009.

- Schiller, Ferdinand Canning Scott. Formal logic, a scientific and social problem. London: Macmillan, 1912.

- Welton, James. "Fallacies incident to the method". A Manual of Logic, Vol. 2. London: W.B. Clive University Tutorial Press, 1905.