| Criminology and penology |

|---|

|

The separate system is a form of prison management based on the principle of keeping prisoners in solitary confinement. When first introduced in the early 19th century, the objective of such a prison or "penitentiary" was that of penance by the prisoners through silent reflection upon their crimes and behavior, as much as that of prison security. More commonly however, the term "separate system" is used to refer to a specific type of prison architecture built to support such a system.

Early British prisons

Millbank Prison was a prison in Millbank, Westminster, London. It was originally constructed as the National Penitentiary and for part of its history served as a holding facility for convicted prisoners before they were transported to Australia. It was opened in 1816 and closed in 1890.

Pentonville Prison in the Barnsbury area of North London had a central hall with five radiating wings, all visible to staff at the center. It opened in 1842 and had separate cells for 520 prisoners.

Eastern State Penitentiary: Basis for many 19th-century prisons

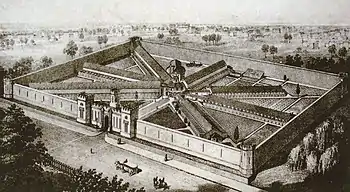

The first prison built in the United States according to the separate system was the Eastern State Penitentiary in 1829 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Its design was later copied by more than 300 prisons worldwide. Its revolutionary system of incarceration, dubbed the "Pennsylvania System" or separate system, originated and encouraged separation of inmates from one another as a form of rehabilitation.

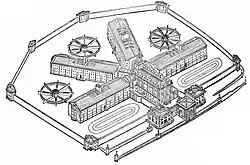

Common features of a separate system prison include a central hall, with several (from four to eight) radiating wings of prison blocks, separated from the central hall and from each other by large metal bars. While all the prison blocks are visible to the prison staff positioned at the centre, individual cells cannot be seen unless the staff enter individual prison blocks. This is in contrast to the panopticon prisons.

The spaces between the prison blocks and the prison wall are used as exercise yards. When the separate system was first introduced, prisoners were required to be in solitary confinement even during exercise; as a result panopticon-style structures were erected inside these yards, in which a guard post was surrounded by tiny, cell-like, one-person exercise "yards". By the end of the 19th century, these structures were removed in favour of more open—if communal—exercise yards. However, in certain prisons such as Pentonville, in London, even during communal exercise, prisoners were required to wear masks in silent isolation.[1]

Many of these separate system prisons from the 19th century continue to house prisoners to this day; moreover, the separate system continues to influence modern prison architecture.

Other elements

Designers of these penal institutions drew heavily on monastic solitary confinement to both destroy the identity of the inmate (and thus make him easier to control) and to crush the "criminal subculture" that flourished in densely populated prisons.

Prisoners incarcerated in separate system prisons were reduced to numbers, their names, faces, and past histories eliminated. The guards and warders charged with overseeing these prisoners knew neither their names nor their crimes, and were prohibited from speaking to them. Prisoners were hooded upon exiting a cell, and even wore felted shoes to muffle their footsteps. The result was a dumb obedience and a passive disorientation that shattered the "criminal community."[2] The regime extended to the prison chapel, Lincoln Castle, which was used as a gaol in the early Victorian period, in which the prisoners could all see the chaplain, but not each other. It was also used in the prison chapel of Port Arthur, Tasmania, where many convicts were taken upon transport to Australia.

See also

Similar or related types of imprisonments and prisons include:

References

- ↑ "Victorian London - Publications - Social Investigation/Journalism - the Criminal Prisons of London and Scenes of London Life (The Great World of London), by Henry Mayhew and John Binny, 1862 - the Convict Prisons of London - Pentonville Prison".

- ↑ Hughes, Robert. The Fatal Shore. New York: Knopf, 1986. 518.

Further reading

Henriques, U. R. Q. (1972). "The Rise and Decline of the Separate System of Prison Discipline". Past and Present. 54: 61–93. doi:10.1093/past/54.1.61.

Forsythe, B. (1980). "The Aims and Methods of the Separate System". Social Policy & Administration. 14 (3): 249–256. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9515.1980.tb00622.x.