The Lord Noel-Baker | |

|---|---|

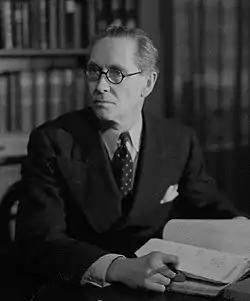

Philip Noel-Baker in 1942 | |

| Minister of Fuel and Power | |

| In office 15 February 1950 – 31 October 1951 | |

| Preceded by | Hugh Gaitskell |

| Succeeded by | Office Abolished |

| Secretary of State for Commonwealth Relations | |

| In office 7 October 1947 – 28 February 1950 | |

| Preceded by | The Viscount Addison |

| Succeeded by | Patrick Gordon Walker |

| Member of Parliament for Derby South (Derby 1936–1950) | |

| In office 9 July 1936 – 29 May 1970 | |

| Preceded by | J.H. Thomas |

| Succeeded by | Walter Johnson |

| Member of Parliament for Coventry | |

| In office 30 May 1929 – 6 October 1931 | |

| Preceded by | Archibald Boyd-Carpenter |

| Succeeded by | William Strickland |

| Member of the House of Lords Lord Temporal | |

| In office 22 July 1977 – 8 October 1982 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Philip John Baker 1 November 1889 Brondesbury Park, London |

| Died | 8 October 1982 (aged 92) Westminster, London |

| Alma mater | Haverford College King's College, Cambridge |

| Awards | Nobel Peace Prize |

| Medal record | ||

|---|---|---|

| Athletics | ||

| Representing | ||

| Olympic Games | ||

| 1920 Antwerp | 1500 m | |

Philip John Noel-Baker, Baron Noel-Baker, PC (1 November 1889 – 8 October 1982), born Philip John Baker, was a British politician, diplomat, academic, athlete, and renowned campaigner for disarmament. He carried the British team flag and won a silver medal for the 1500m at the 1920 Summer Olympics in Antwerp, and received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1959.[1]

Noel-Baker is the only person to have won an Olympic medal and received a Nobel Prize.[2] He was a Labour Member of Parliament (UK) for 36 years, serving from 1929 to 1931 and again from 1936 to 1970, serving in several ministerial offices and the cabinet. He became a life peer in 1977.

Early life and athletic career

Baker was born in Brondesbury Park, London,[3] the sixth of seven children of the Canadian-born Quaker, Joseph Allen Baker and the Scottish-born Elizabeth Balmer Moscrip. His father had moved to England in 1876 to establish a manufacturing business and served as a Progressive member of the London County Council from 1895 to 1906 and as a Liberal member of the House of Commons for East Finsbury from 1905 to 1918.

Baker was educated at Ackworth School, Bootham School, and then in the US at the Quaker-associated Haverford College in Pennsylvania. He studied at King's College, Cambridge, from 1908 to 1912. As well as being an excellent student, obtaining a second in Part I history and a first in Part II economics, he was President of the Cambridge Union Society in 1912 and President of the Cambridge University Athletic Club from 1910 to 1912.[3]

He was a competitor in the Olympic Games as a middle-distance runner, both before and after the First World War, representing Great Britain in the 800 metres and 1500 metres at the 1912 Olympic Games in Stockholm.[4] He reached the final of the 1500 metres, won by his fellow countryman Arnold Jackson. At the 1920 Summer Olympics in Antwerp Baker was captain of the British track team and carried the team's flag. He won his first race in the 800 metres, but then concentrated on the 1500 metres, taking the silver medal behind his teammate Albert Hill.[5] He was captain again at the 1924 Summer Olympics in Paris, but did not compete.[3]

Baker's early career was as an academic. In 1914 he was appointed as vice-principal of Ruskin College, Oxford, and in 1915 was elected a fellow at King's College, Cambridge.[3] During World War I, he organised and led the Friends' Ambulance Unit attached to the fighting front in France (1914–1915), and was then, as a conscientious objector from 1916, adjutant of the First British Ambulance Unit for Italy, in association with the British Red Cross (1915–1918), for which he received military medals from the UK, France and Italy.[5]

Political career

After World War I, Noel-Baker was closely involved in the formation of the League of Nations, serving as assistant to Lord Robert Cecil, then assistant to Sir Eric Drummond, the league's first secretary-general. According to historian Susan Pedersen "Baker was far to the left of Drummond politically, but he had the kind of formation, connections, and intimate understanding of British officialdom’s rules of the game that made for easy collaboration between the two."[6] Noel-Baker did much of the League's early work on the mandates system.[6]

He became the first Sir Ernest Cassel Professor of International Relations at the London School of Economics (which was then part of the University of London) from 1924 to 1929[7] and a lecturer at Yale University from 1933 to 1934. His political career with the Labour Party began in 1924 when he stood, unsuccessfully, for Parliament in the Conservative safe seat of Birmingham Handsworth. He was elected as the member for Coventry in 1929, and served as parliamentary private secretary to the Foreign Secretary Arthur Henderson.[8]

Noel-Baker lost his seat in 1931, but remained Henderson's assistant while Henderson was president of the World Disarmament Conference in Geneva in 1932 to 1933. He stood for Parliament again in Coventry in 1935, unsuccessfully, but won the Derby by-election in July 1936 after the sitting Derby Member of Parliament J. H. Thomas resigned. When that constituency was split in 1950, he transferred to Derby South.

Noel-Baker became a member of the Labour Party's National Executive Committee in 1937. On 21 June 1938, Noel-Baker, as M.P. for Derby, in the run up to World War II, spoke at the House of Commons against aerial bombing of German cities based on moral grounds. "The only way to prevent atrocities from the air is to abolish air warfare and national air forces altogether."[9]

In the coalition government during the World War II he was a parliamentary secretary at the Ministry of War Transport from February 1942, and served as Minister of State for Foreign Affairs after Labour gained power following the 1945 general election, but had a poor relationship with the Foreign Secretary, Ernest Bevin. Noel-Baker moved to become Secretary of State for Air in October 1946, and then became Secretary of State for Commonwealth Relations in 1947 and joined the cabinet.[10]

Noel-Baker was the minister responsible for organising the 1948 Olympic Games in London. He moved to the Ministry of Fuel and Power in 1950. In the mid-1940s, Noel-Baker served on the British delegation to what became the United Nations, helping to draft its charter and other rules for operation as a British delegate. He served as Chairman of the Labour Party in 1946–47, but lost his place on the National Executive Committee in 1948, his place being taken by Michael Foot.[11] An opponent of left-wing Bevanite policies in the 1950s, and an advocate of multilateral nuclear disarmament, rather than a policy of unilateral disarmament, he received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1959. In 1979, with Fenner Brockway, he co-founded the World Disarmament Campaign, serving as co-Chair until he died,[12][13] and was an active supporter of disarmament into the 1980s.

Noel-Baker stood down as the MP for Derby South at the 1970 general election, at which he was succeeded by Walter Johnson. His life peerage was announced in the 1977 Silver Jubilee and Birthday Honours[14] and, aged 87, he was raised to the peerage 22 July 1977, as Baron Noel-Baker, of the City of Derby,[15][16] having declined an appointment as a Companion of Honour in the 1965 New Year Honours. He was president of the International Council of Sport Science and Physical Education from 1960 to 1976.[3] Noel-Baker was an active contributor to House of Lords debates into his nineties, speaking in debates on the ongoing Falklands War in the months preceding his death.

A memorial garden, the Philip Noel-Baker Peace Garden, exists within Elthorne Park, a small park in the London Borough of Islington.

Brian Harrison recorded an oral history interview with Noel-Baker, in April 1977, as part of the Suffrage Interviews project, titled Oral evidence on the suffragette and suffragist movements: the Brian Harrison interviews.[17] Noel-Baker discusses the League of Nations Union and the Peace Ballot of 1934-35, as well as his work with the United Nations Association and the work of Kathleen Courtney.

Personal life

In June 1915, Philip John Baker married Irene Noel, a field hospital nurse in East Grinstead, subsequently adopting the hyphenated name Noel-Baker in 1921 by deed poll.[18] His wife was a friend of Virginia Woolf. Their only son, Francis, also became a Labour MP and served together with his father in the Commons. Their marriage, however was not a success and Noel-Baker's mistress from 1936 was Megan Lloyd George, daughter of the former Liberal Party leader David Lloyd George, herself a Liberal and later Labour MP. The relationship ended when Irene died in 1956.[3]

He died at home in Westminster on 8 October 1982.[3]

Works

Writings

- Noel-Baker, Philip (1926). Disarmament. London: The Hogarth Press. (Reprint 1970, New York: Kennicat Press)

- Noel-Baker, Philip (1926). The League of Nations at Work. London: Nisbet.

- Noel-Baker, Philip (1927). Disarmament and the Coolidge Conference. London: Leonard & Virginia Woolf.

- Noel-Baker, Philip (1929). The Present Juridical Status of the British Dominions in International Law. London: Longmans.

- Noel-Baker, Philip (1934). Disarmament. London: League of Nations Union.

- Noel-Baker, Philip (1934). Hawkers of Death: The Private Manufacture and Trade in Arms. London: Labour Party.

- Noel-Baker, Philip (1936). The Private Manufacture of Armaments. London: Victor Gollancz. (Reprint 1972, New York: Dover Publications)

- Noel-Baker, Philip (1944). Before we go back: a pictorial record of Norway's fight against Nazism. London: H.M.S.O.

- Noel-Baker, Philip (1946). U.N., the Atom, the Veto (speech at the Plenary Assembly of the United Nations 25 October 1946). London: The Labour Party.

- Noel-Baker, Philip (1958). The Arms Race: A Programme for World Disarmament. London: Stevens & Sons. ASIN: B0000CJZPN.

- Noel-Baker, Philip (1962). Nansen's Place in History. Oslo: Universitetsförlaget.

- Noel-Baker, Philip (1963). The Way to World Disarmament-Now!. London: Union of Democratic Control.

- Noel-Baker, Philip (1979). The first World Disarmament Conference, 1932–1933 and why it failed. Oxford: Pergamon. ISBN 0-08-023365-1.

By Philip Noel-Baker with other authors

- Buzzard, Rear-Admiral Sir Anthony; Noel-Baker, Philip (1959). Disarmament and Defence. United Nations [Peacefinder Pamphlet. no. 28].

- Mountbatten, Louis; Noel-Baker, Philip; Zuckerman, Solly (1980). Apocalypse now?. Nottingham: Spokesman Books. ISBN 0-85124-297-9.

See also

References

- ↑ "Philip Noel-Baker; The Nobel Peace Prize 1959". Nobelprize.org. The Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 21 October 2008.

- ↑ "Olympic Games trivia for pedants" Archived 9 August 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Canberra Times, 2 August 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Howell, David. "Baker, Philip John Noel-, Baron Noel-Baker". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/31505. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ "Philip Noel-Baker". Olympedia. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- 1 2 Evans, Hilary; Gjerde, Arild; Heijmans, Jeroen; Mallon, Bill; et al. "Philip Baker". Olympics at Sports-Reference.com. Sports Reference LLC. Archived from the original on 17 April 2020.

- 1 2 Pedersen, Susan (2015). The Guardians: The League of Nations and the Crisis of Empire. Oxford University Press. pp. 48–49. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199570485.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-957048-5.

- ↑ "Lord Philip Noel-Baker, Nobel Prize Winner". London School of Economics. Archived from the original on 7 December 2008. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- ↑ Noel-Baker, Philip (1925). The Geneva Protocol for the Pacific Settlement of International Disputes. London: P.S. King & Son Ltd.

- ↑ P.J. Noel-Baker comments on air warfare, ww2db.com; accessed 7 December 2014.

- ↑ "New Ministers at Palace". Derby Daily Telegraph. 14 October 1947. Retrieved 2 November 2015 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ↑ "NOEL-BAKER DROPPED". Gloucester Echo. 18 May 1948. Retrieved 2 November 2015 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ↑ Philip Noel-Baker on Nobelprize.org

- ↑ Whittaker, David J. (1989). Fighter for peace: Philip Noel-Baker 1889–1982. York: Sessions. ISBN 1-85072-056-8.

- ↑ "No. 47234". The London Gazette (Supplement). 10 June 1977. p. 7080.

- ↑ "No. 47285". The London Gazette. 26 July 1977. p. 9679.

- ↑ "No. 20121". The Edinburgh Gazette. 26 July 1977. p. 861.

- ↑ London School of Economics and Political Science. "The Suffrage Interviews". London School of Economics and Political Science. Retrieved 5 December 2023.

- ↑ "No. 32613". The London Gazette (Supplement). 17 February 1922. p. 1455.

Bibliography

Primary and Secondary Sources

- Ferguson, John (1983). Philip Noel-Baker: the man and his message. London: United Nations Association. ASIN: B0000EF3NF.

- Lloyd, Lorna: Philip Noel-Baker and the Peace Through Law in Long, David; Wilson, Peter, eds. (1995). Thinkers of the Twenty Years' Crisis. Inter-War Idealism reassessed. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-827855-1.

- Russell, Bertrand; Russell, B. (1960). "Philip Noel-Baker: A Tribute". International Relations. 2: 1–2. doi:10.1177/004711786000200101. S2CID 145544869.

External links

- Hansard 1803–2005: contributions in Parliament by Philip Noel-Baker

- "Archival material relating to Philip Noel-Baker". UK National Archives.

- Philip John Noel-Baker at Olympics.com

- Philip Baker at Olympic.org (archived)

- "The Papers of Philip Noel-Baker (Churchill/NBKR)". Churchill Archives Centre. Retrieved 2 June 2007. (timeline of Noel-Baker's life, and index to his papers held at Churchill Archives Centre, Churchill College, Cambridge)

- Newspaper clippings about Philip Noel-Baker in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW