Phil May | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Philip William May 22 April 1864 |

| Died | 5 August 1903 (aged 39) St John's Wood, London, England |

Philip William May (22 April 1864 – 5 August 1903) was an English caricaturist who, with his vigorous economy of line, played an important role in moving away from Victorian styles of illustration towards the creation of the modern humorous cartoon.

Biography

Phil May was born at Wortley, near Leeds, the son of an engineer, who died when May was nine years old. His mother was the daughter of Eugene Macarthy, one time manager of the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane. She was left in very poor circumstances and the family had a great struggle to exist.

May's grandfather, a country gentleman, had some talent as a draughtsman and liked drawing caricatures. At the age of twelve, in Leeds, May became friendly with Fred Fox, whose father was the scenic artist at the recently opened Grand Theatre. That gave him a free run of the theatre, where he used to sketch sections of other people's designs for costumes, as well as sketching actors' portraits, for which he received one shilling, later rising to five shillings. Another of his contemporaries was Walter Curtis, who became prominent as a music hall comedian and general entertainer.

_(LOC)_(15585476586).jpg.webp)

May had begun to earn his living in a solicitor's office; before he was fifteen he had acted as time-keeper at a foundry, had tried to become a jockey and had been on the stage at Scarborough and Leeds. When only fourteen years old, had drawings accepted for the Yorkshire Gossip. When he was about seventeen he went to London with a sovereign in his pocket. He suffered extreme want, sleeping out in the parks and streets, until he obtained employment as designer to a theatrical costumier. He also drew posters and cartoons, and for about two years worked for the St Stephens Review, until he was advised to go to Australia for his health.

During the three years (1886–1889) he spent in Australia he was attached to The Sydney Bulletin, or The Bulletin as it was better known, for which many of his best drawings were made. He produced about 800 drawings for The Bulletin. On his return to Europe he went to Paris by way of Rome, where he worked hard for some time, before he appeared in 1892 in London to resume his interrupted connection with the St Stephens Review. His studies of the London guttersnipe and the coster-girl rapidly made him famous. His overflowing sense of fun, his genuine sympathy with his subjects, and his kindly wit were on a par with his artistic ability.

While drawing for The Bulletin he would produce the illustration “The Mongolian Octopus” (1886),[1] an anti-Chinese cartoon which has been described as “the most scandalous and racist cartoon ever to grace the Australian media”.[2] The Bulletin’s motto at this time was “Australia for the White Man”; May himself has been described as “openly racist and anti-Semitic”.[3]

It was often said that the extraordinary economy of line which was a characteristic feature of his drawings had been forced upon him by the deficiencies of the printing equipment of the Sydney Bulletin. It was in fact the result of a laborious process which involved a number of preliminary sketches, and a carefully considered system of elimination. His later work included some excellent political portraits. He became a regular member of the staff of Punch in 1896, and in his later years his services were retained exclusively for Punch and The Graphic. In 1898, he was a founder member of the London Sketch Club. He died from tuberculosis in 1903 at his home in St John's Wood, London.[4]

Influence and reputation

May was a major influence on the style of cartoon drawing in the 20th century. In 1918, Percy Bradshaw wrote in The Art of the Illustrator that May "surely gave more magic to a single line than any draftsman who has ever lived, and he was unquestionably the creator of the simplified technique of modern humorous drawing".[5] May's work was a major influence on David Low. Low recalled that his early aspirations were dampened when he saw the "intricate technical quality" of most Punch cartoons, which seemed too difficult to emulate: "But then I came on Phil May, who combined quality with apparent facility ... Once having discovered Phil May I never let him go."[6]

There was an exhibition of May's drawings at the Fine Art Society in 1895, and another at the Leicester Galleries in 1903. A selection of his drawings contributed to the periodical press. Examples of his work can be found at the leading Australian galleries, the Victoria and Albert Museum, the British Museum, and around three hundred drawings and watercolours are in the collection of Leeds Art Gallery. From 1892 to 1904 there were thirteen editions of Phil May's Illustrated Winter Annual, with three supplemental Summer Annuals.[4] In addition to his Summer and Winter Annuals, various collections were published, including Phil May's Sketch Book (1895), Phil May's Guttersnipes (1896), Phil May's Graphic Pictures and Phil May's A. B. C. (1897), Phil May's Album (1899), Phil May, Sketches from Punch (1903). Posthumous publications include Phil May in Australia (1904), The Phil May Folio (1904), and Humorists of the Pencil, Phil May (1908).

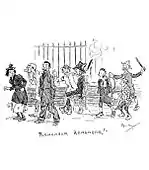

Gallery

"Information wanted: 'Say, boy, do my boots want cleaning?'," 1891.

"Information wanted: 'Say, boy, do my boots want cleaning?'," 1891. "The first smoke."

"The first smoke." "Remember, remember."

"Remember, remember." William Ewart Gladstone, 1890.

William Ewart Gladstone, 1890. "I fear no foe," 1894.

"I fear no foe," 1894.

Portraits

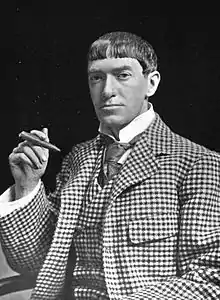

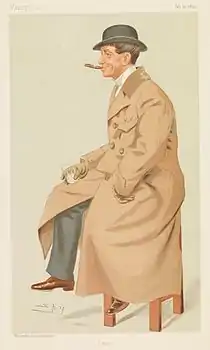

"Phil May as seen by himself".

"Phil May as seen by himself". Phil May, by C.D. Gibson.

Phil May, by C.D. Gibson. Sketch of May, by Hy Mayer, 1899.

Sketch of May, by Hy Mayer, 1899. Self-portrait by May.

Self-portrait by May. "Phil May drawn by himself".

"Phil May drawn by himself".

References

- ↑ Hansen, Guy (19 May 2015). "Australia for the white man". National Library of Australia. Retrieved 18 July 2022.

- ↑ "Racism rife aboard the Shanghai Trader". The Canberra Times. Vol. 60, no. 18592. Canberra, ACT, Australia. 27 August 1986. p. 17.

- ↑ Grishin, Sasha (22 May 2019). "Inked: Australian Cartoons at the National Library of Australia will make you think more than laugh". The Canberra Times. Retrieved 18 July 2022.

- 1 2 Heseltine, H.P. "Philip William (Phil) May (1864–1903)". May, Philip William (Phil) (1864–1903). Australian National University. Retrieved 20 August 2014.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ↑ Bradshaw, The Art of the Illustrator, 1918.

- ↑ Low, David, Low's Autobiography, London, Michael Joseph, 1956, p. 27.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "May, Phil". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 19 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 730.

- Serle, Percival (1949). "May, Philip William". Dictionary of Australian Biography. Sydney: Angus & Robertson.

Bibliography

- Simon Houfe : Phil May: His Life and Work 1864-1903, Aldershot, Hants: Ashgate, ISBN 9781840146523 OCLC 46731137

- James Thorpe: English Masters of Black-and-White: Phil May, Art and Technics, 1948

External links

- Phil May and Leo Cheney Collection from the University of Salford site

- Works by Phil May at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Philip William May at Faded Page (Canada)

- Works by or about Phil May at Internet Archive

- Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University: Phil May sketch book, circa 1896

- Phil May at Library of Congress, with 27 library catalogue records