Pierre-Clément de Laussat | |

|---|---|

Portrait by unknown artist | |

| 2nd Commandant of French Guiana | |

| In office 1819–1823 | |

| Monarch | Louis XVIII |

| Preceded by | Claude Carra de Saint-Cyr |

| Succeeded by | Pierre Bernard Milius |

| 2nd Colonial Prefect of Martinique | |

| In office 1804–1809 | |

| Monarch | Napoléon I |

| Preceded by | Charles-Henri Bertin |

| Succeeded by | Sir George Beckwith British Occupation |

| 1st Colonial Prefect of Louisiana (French First Republic) | |

| In office 1803–1803 | |

| Monarchs | Napoléon Bonaparte First Consul of France |

| Preceded by | Juan Manuel de Salcedo as Spanish Governor of Louisiana |

| Succeeded by | William C.C. Claiborne as Governor of the Territory of Orleans William Henry Harrison Sr. as Governor of the Louisiana District |

| Personal details | |

| Born | November 23, 1756 Pau, France |

| Died | April 10, 1835 (aged 78) Bernadets, France |

| Spouse |

Marie-Anne-Joséphine de Péborde de Pardiès

(m. 1790; died 1827) |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Awards | Order of Saint Louis Chevalier |

Pierre-Clément de Laussat (French pronunciation: [pjɛʁ klemɑ̃ də losa]; 23 November 1756 – 10 April 1835) was a French politician, and the 24th Colonial Governor of Louisiana, the last under French rule. He later served as colonial official in Martinique and French Guiana, as well as an administrator in France and Antwerp.

Biography

Laussat was born in the town of Pau. After serving as receveur général des finances in Pau and Bayonne from 1784 to 1789,[1] he was imprisoned during the Terror, but was released and recruited in the armée des Pyrénées. On April 17, 1797, he was elected to the Council of Ancients. After the coup of 18 Brumaire, he entered the Tribunat on December 25, 1798.[2]

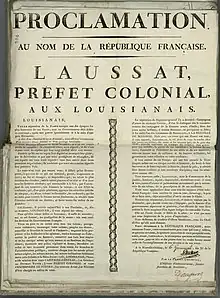

He was appointed by the soon-to-be Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte to be colonial prefect (sort of governor, a high-ranked position in the French administration newly created by Napoleon that still exist to this day) of Louisiana in August 1802 and arrived in the colony on March 26, 1803.[3] In his procolomation introducing himself and his fellow Republican colonial administrators, Laussat described the transfer of Louisiana from France to Spain as "... one of the most shameful epochs of her [France's] glory, under an already weak and corrupt Government, after an ignominious war and following a withering peace." He praised Bonaparte's desire to regain Louisiana and to see the colony thrive.[4] Laussat also provided an outline for how the colony would be governed with a captain general overseeing internal and external defense of the colony; a colonial prefect overseeing administration and finances; and a commissary of justice overseeing civil and criminal tribunals.[5] Two weeks later, Bonaparte made his decision to sell Louisiana to the United States.[3]

Laussat was initially only to be the interim head of Louisiana until arrival of the Governor General Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte appointed by Bonaparte. However, when Bonaparte rejected Bernadotte's request for additional settlers and support for the posting, Bernadotte declined the governorship.[6] This left Laussat ruling as governor for several months, during which time he abolished the local cabildo and then published the Napoleonic Code in the colony.[7]

Laussat envisioned bringing forth a rebirth of a prosperous French La Nouvelle-Orléans; however, not all Louisianans were eager to see Republican France in control of the city. Three-fifths of the Ursaline sisters in New Orleans, along with their mother-superior, decided to abandon the city and head to Havana when the Spanish handed over the city.[8] Lassat and other French officials were contemptuous towards the Spanish officials in charge of the territory; he contrasted the "Spanish spirit" as senile, corrupt, racially weak and effeminately degenerate with the "austerity, efficiency, and virility" of Bonapartist republicanism.[9]

Within several months, Laussat heard that Louisiana had been sold to the U.S., but he did not believe it. On July 28, 1803, he wrote to the French government to inquire whether the rumor was true.[3] On August 18, 1803, he received word from Bonaparte that France had declared war on Great Britain and that he was to transfer Louisiana to the United States.[10][11]

On November 30, 1803, Laussat served as commissioner of the French government in the retrocession of Louisiana from Spain to France. A few weeks later, on December 20, 1803, Laussat transferred the colony to the U.S. representatives, William C.C. Claiborne and James Wilkinson.[3]

On April 21, 1804, Laussat left Louisiana to become colonial prefect of Martinique, serving until 1809 when he was captured and imprisoned by the British.[12]

In 1810, Laussat returned to France and sought a new governmental posting. He was sent to the French Netherlands to oversee the port of occupied Antwerp (1810–1812) and then to serve as prefect of Jemmape (1812–1814). During the Hundred Days, he served as prefect of Pas-de-Calais until the defeat of Napoleon at Waterloo.[13]

During the Bourbon Restoration, he served as commandant of French Guiana from 1819 to 1823,[14] during which time he advanced efforts to attract American farmers and settlers to the colony. Laussat had been impressed during his short tenure in Louisiana by the way Americans had settled the trans-Appalachian region and he envisioned a similar settlement plan for a site in the Kourou watershed. Only two small groups arrived to found the short-lived settlement of Laussadelphie.[15]

In 1823, Laussat retired to his ancestral château in France where he died in 1835.

Personal life

In September 1790, Laussat married Marie-Anne-Joséphine de Péborde de Pardiès (1768–1827), the daughter of Laussat's mentor, Jean-Nicolas de Péborde, seigneur de Cardesse.[16] They had three daughters — Zoé, Sophie, and Camille — and one son, Lysis Baure Pierre.[17]

Bibliography

- Laussat, Pierre-Clément de (1831). Mémoires sur ma vie à mon fils: pendant les années 1803 et suivantes, que j'ai rempli des fonctions publiques, savoir à la Louisianne, en qualité de commissaire du gouvernement français pour la reprise de possession de cette colonie et pour sa remise aux Etats-Unis; à la Martinique, comme préfet colonial; à la Guyane française, en qualité de commandant et administrateur pour le roi [Memoirs on my Life to My Son During the Years 1803 and following, that I Filled Public Office in Louisiana, as Commissioner of the French Government for the Repossession of This Colony and for Surrender to the United States; in Martinique, as Colonial Prefect; and in French Guiana, as Commander and Administrator for the King] (in French). Pau, France: É. Vignancour, Imprimeur - Libaire. Retrieved 2 November 2018.

- Laussat, Pierre Clement de (1978). Bush, Robert D. (ed.). Memoirs of My Life: Beyond the Bayou. Translated by Pastwa, Agnes-Josephine. Baton Rouge, Louisiana: LSU Press. ISBN 978-0-8071-2870-1. Retrieved 2 November 2018.

- Laussat, Pierre-Clément de (1989). Lebel, Maurice (ed.). Louisiana, Napoleon and the United States: An Autobiography of Pierre-Clément de Laussat, 1756-1835. Translated by Pastwa, Agnes-Josephine. Lanham, Maryland: University Press of America. ISBN 978-0-8191-7448-2. Retrieved 2 November 2018.

- Kuka, Jon; Rosal, Angelita; Lemmon, Alfred Emmette, eds. (1993). A Guide to the Papers of Pierre Clément Laussat: Napoleon's Prefect for the Colony of Louisiana and of General Claude Perrin Victor at the Historic New Orleans Collection. New Orleans, Louisiana: The Historic New Orleans Collection. ISBN 978-0-917860-33-1. Retrieved 2 November 2018.

References

- ↑ Révérend, Albert (1904). Titres, anoblissements et pairies de la restauration 1814–1830 [Titles, Ennobles and Peerages of the Restoration, 1814–1830] (in French). Vol. 4. Paris, France: Chez Honoré Champion. p. 223.

- ↑ Kukla, Jon (1993). "Introduction". In Kukla, Jon; Rosal, Angelita; Emmette Lemmon, Alfred (eds.). A Guide to the Papers of Pierre Clément Laussat, Napoleon's Prefect for the Colony of Louisiana and of General Claude Perrin Victor at the Historic New Orleans Collection. New Orleans, Louisiana: The Historic New Orleans Collection. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-917860-33-1.

- 1 2 3 4 Berry, Jason (2018). City of a Million Dreams: A History of New Orleans at Year 300. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press. pp. 75–76. ISBN 978-1-4696-4715-9.

- ↑ de Laussat, Pierre-Clément. "Proclamation. Au Nom de la République Française." (1803-03-27) [document]. France aux Amériques, File: FR ANOM C 13A 52 Fo 304. Paris, France: Archives nationales d'outre-mer, Bibliothèque nationale de France: Gallica.

- ↑ "Extract From the Register of the Deliberations of the Consuls of the Republic". Alexandria Advertiser and Commercial Intelligencer. Vol. 3, no. 75. 18 May 1803. pp. 2–3 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Olivier, Jean-Marc (2010). "Bernadotte, Bonaparte, and Louisiana: the last dream of a French Empire in North America" (PDF). In Belaubre, Christope; Dym, Jordana; Savage, John (eds.). Napoleon's Atlantic: The Impact of Napoleonic Empire in the Atlantic World. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill. pp. 141–150. ISBN 978-9004181540. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- ↑ "Return of Brief French Rule 1803". Colonial Law in New Orleans, 1718–1803: Olde World Law in a New Land. New Orleans, Louisiana: The Law Library of Louisiana. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ↑ Berry, Jason (2018). "City of Migrants". City of a Million Dreams: New Orleans at Year 300. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press. pp. 61–77. doi:10.5149/northcarolina/9781469647142.003.0004. ISBN 978-1-4696-4714-2. S2CID 204680289.

- ↑ Faber, Eberhard L. (2017). ""The Spanish Spirit in this Country": Newcomers to Louisiana in 1803–1805, and Their Perceptions of the Spanish Regime". Tulane European and Civil Law Forum. 31/32: 22. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- ↑ Langlois, Gilles-Antoine (2004). "La Nouvelle Orleans: Etat Sommaire des Espaces Urbains et Sociaux a l'Époque de Pierre Clement des Laussat (Mars 1803-Avril 1804)" [New Orleans: Summary of the State of Urban and Social Spaces at the Time of Pierre Clement de Laussat (March 1803-April 1804)]. French Colonial History (in French). 5 (1): 111–124. doi:10.1353/fch.2004.0009. ISSN 1543-7787. S2CID 144263112.

- ↑ Rodriguez, Junius P. (2002). The Louisiana Purchase: A Historical and Geographical Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. p. 181. ISBN 978-1-57607-188-5. Retrieved 2 November 2018.

- ↑ Fortier, Alcée (1914). Louisiana: Comprising Sketches of Parishes, Towns, Events, Institutions, and Persons, Arranged in Cyclopedic Form. Vol. 2. Century Historical Association. p. 52.

- ↑ Staes, Jacques (April 2003). "Une Lettre de Pierre-Clément de Laussat Concernant la Situation Religieuse en Béarn (1788)" [A Letter from Pierre-Clément de Laussat Concerning the Religious Situation in Béarn (1788)] (PDF). Centre d'Étude du Protestantisme Béarnais (in French) (33): 23–25. Retrieved 2 November 2018.

- ↑ Puyo, Jean-Yves Puyo (2008). "Mise en valeur de la Guyane française et peuplement blanc: les espoirs déçus du baron de Laussat (1819-1823)" [Enhancement of French Guiana and White Settlement: The Disappointed Hopes of Baron de Laussat (1819-1823)]. Journal of Latin American Geography (in French). 7 (1): 177–202. doi:10.1353/lag.2008.0005. JSTOR 25765204. S2CID 145324296.

- ↑ Boromé, Joseph A. (1967). "When French Guiana Sought American Settlers". Caribbean Studies. 7 (2): 39–51. ISSN 0008-6533. JSTOR 25612004.

- ↑ Laussat (1989), pp. 48–50.

- ↑ Laussat (1831), pp. vii–viii.