| Piriformis muscle | |

|---|---|

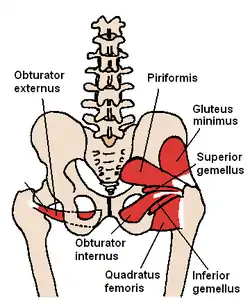

Buttocks seen from behind (the piriformis and the rest of the lateral rotator group are visible) | |

Muscles of the gluteal and posterior femoral regions seen from the front | |

| Details | |

| Origin | Sacrum |

| Insertion | Greater trochanter |

| Artery | Inferior gluteal, lateral sacral and superior gluteal artery, |

| Nerve | Nerve to the piriformis (L5, S1, and S2) |

| Actions | External rotator of the thigh |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Musculus piriformis |

| TA98 | A04.7.02.011 |

| TA2 | 2604 |

| FMA | 19082 |

| Anatomical terms of muscle | |

The piriformis muscle (from Latin piriformis 'pear-shaped') is a flat, pyramidally-shaped muscle in the gluteal region of the lower limbs. It is one of the six muscles in the lateral rotator group.

The piriformis muscle has its origin upon the front surface of the sacrum, and inserts onto the greater trochanter of the femur. Depending upon the given position of the leg, it acts either as external (lateral) rotator of the thigh or as abductor of the thigh. It is innervated by the piriformis nerve.

Structure

The piriformis is a flat muscle, and is pyramidal in shape.[1]

Origin

The piriformis muscle originates from the anterior (front) surface of the sacrum[2][3] by three fleshy digitations attached to the second, third, and fourth sacral vertebra.[1]

It also arises from the superior margin of the greater sciatic notch, the gluteal surface of the ilium (near the posterior inferior iliac spine), the sacroiliac joint capsule, and (sometimes) the sacrotuberous ligament (more specifically, the superior part of the pelvic surface of this ligament).[3]

Insertion

The muscle inserts onto the greater trochanter of the femur[2] (its tendon often unites with the tendons of the superior gemellus, inferior gemellus, and obturator internus muscles prior to insertion).

Innervation

The piriformis muscle is innervated by the piriformis nerve.[2]

Relations

The posterior aspect of the muscle lies against the sacrum. The anterior surface of the muscle is related to the rectum (especially on the left side of the body), and the sacral plexus.[3]

The muscle lies almost parallel with the posterior margin of the gluteus medius. It is situated partly within the pelvis against its posterior wall, and partly at the back of the hip joint.

It exits the pelvis through the greater sciatic foramen[1] superior to the sacrospinous ligament.[3]

Variation

In around 80% of the population, the sciatic nerve travels below the piriformis muscle.[2][1] In 17% of people, the piriformis muscle is pierced by parts or all of the sciatic nerve.[2] Several variations occur, one of which is the rarely found Beaton's type-b where the sciatic nerve divides between and below the piriformis.[4]

It may be united with the gluteus medius, send fibers to the gluteus minimus, or receive fibers from the superior gemellus.

It may have one or two sacral attachments; or it may be inserted into the capsule of the hip joint.

Function

The piriformis muscle is part of the lateral rotators of the hip, along with the quadratus femoris, gemellus inferior, gemellus superior, obturator externus, and obturator internus. The piriformis laterally rotates the femur with hip extension and abducts the femur with hip flexion.[2] Abduction of the flexed thigh is important in the action of walking because it shifts the body weight to the opposite side of the foot being lifted, which prevents falling. The action of the lateral rotators can be understood by crossing the legs to rest an ankle on the knee of the other leg. This causes the femur to rotate and point the knee laterally. The lateral rotators also oppose medial rotation by the gluteus medius and gluteus minimus. When the hip is flexed to 90 degrees, piriformis abducts the femur at the hip and reverses primary function, internally rotating the hip when the hip is flexed at 90 degrees or more.[5]

Clinical significance

Piriformis syndrome occurs when the piriformis irritates the sciatic nerve, which comes into the gluteal region beneath the muscle, causing pain in the buttocks and referred pain along the sciatic nerve.[6] This referred pain is known as sciatica. Seventeen percent of the population has their sciatic nerve coursing through the piriformis muscle. This subgroup of the population is predisposed to developing sciatica. Sciatica can be described by pain, tingling, or numbness deep in the buttocks and along the sciatic nerve. Sitting down, stretching, climbing stairs, and performing squats usually increases pain. Diagnosing the syndrome is usually based on symptoms and on the physical exam. More testing, including MRIs, X-rays, and nerve conduction tests can be administered to exclude other possible diseases.[6] If diagnosed with piriformis syndrome, the first treatment involves progressive stretching exercises, massage therapy (including neuromuscular therapy) and physical treatment. Corticosteroids can be injected into the piriformis muscle if pain continues. Findings suggest the possibility that Botulinum toxin type B may be of potential benefit in the treatment of pain attributed to piriformis syndrome.[7] A more invasive, but sometimes necessary treatment involves surgical exploration; however, the side effects of the surgery could be much worse than alternative treatments such as physical therapy. Surgery should always be a last resort.[6]

Landmark

The piriformis is a very important landmark in the gluteal region. As it travels through the greater sciatic foramen, it effectively divides it into an inferior and superior part.

This determines the name of the vessels and nerves in this region – the nerve and vessels that emerge superior to the piriformis are the superior gluteal nerve and superior gluteal vessels. Inferiorly, it is the same, and the sciatic nerve also travels inferiorly to the piriformis.[8]

History

The piriformis muscle was first named by Adriaan van den Spiegel, a professor from the University of Padua in the 16th century.[9]

Additional images

Muscles of the gluteal and posterior femoral regions

Muscles of the gluteal and posterior femoral regions

References

![]() This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 476 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 476 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- 1 2 3 4 Khan, Dost; Nelson, Ariana (2018-01-01), Benzon, Honorio T.; Raja, Srinivasa N.; Liu, Spencer S.; Fishman, Scott M. (eds.), "Chapter 67 - Piriformis Syndrome", Essentials of Pain Medicine (Fourth Edition), Elsevier, pp. 613–618.e1, doi:10.1016/b978-0-323-40196-8.00067-x, ISBN 978-0-323-40196-8, retrieved 2021-02-03

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Pan, Jason; Vasudevan, John (2018-01-01), Freedman, Mitchell K.; Gehret, Jeffrey A.; Young, George W.; Kamen, Leonard B. (eds.), "Chapter 24 - Piriformis Syndrome: A Review of the Evidence and Proposed New Criteria for Diagnosis", Challenging Neuropathic Pain Syndromes, Elsevier, pp. 205–215, ISBN 978-0-323-48566-1, retrieved 2021-02-03

- 1 2 3 4 Standring, Susan (2021). Gray's Anatomy: The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice (42nd ed.). [New York]. p. 1244. ISBN 978-0-7020-7707-4. OCLC 1201341621.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Jha AK, Baral P (2020). "Composite Anatomical Variations between the Sciatic Nerve and the Piriformis Muscle: A Nepalese Cadaveric Study". Case Rep Neurol Med. 2020: 7165818. doi:10.1155/2020/7165818. PMC 7150691. PMID 32292613.

- ↑ Hansen, John T. (2009). Netter's Clinical Anatomy (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders/Elsevier. ISBN 978-1-4377-0272-9. OCLC 316421154.

- 1 2 3 "The piriformis syndrome". Retrieved 2007-11-16.

- ↑ Lang AM (March 2004). "Botulinum toxin type B in piriformis syndrome". American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation. 83 (3): 198–202. doi:10.1097/01.PHM.0000113404.35647.D8. PMID 15043354. S2CID 9738513.

- ↑ "Muscles of the Gluteal Region". TeachMeAnatomy. Retrieved 2012-12-15.

- ↑ Smoll NR (January 2010). "Variations of the piriformis and sciatic nerve with clinical consequence: a review". Clinical Anatomy. 23 (1): 8–17. doi:10.1002/ca.20893. PMID 19998490. S2CID 23677435.

External links

- "Piriformis" University of Washington

- Anatomy photo:13:st-0408 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center - "Gluteal Region: Muscles"

- Anatomy photo:43:15-0101 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center - "The Female Pelvis: The Posterolateral Pelvic Wall"