| Cantaloupe | |

|---|---|

European cantaloupe (true cantaloupe) | |

| Genus | Cucumis |

| Species | C. melo |

| Subspecies | C. melo subsp. melo |

| Cultivar group | Cantalupensis Group (incorporating Reticulatus Group)[1] |

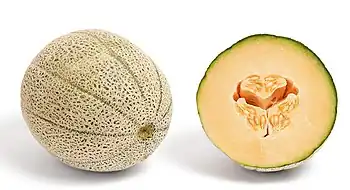

The cantaloupe (/ˈkæn(t)əloʊp/ KAN-(t)ə-lohp) is a type of true melon (Cucumis melo) from the family Cucurbitaceae. Originally, cantaloupe referred only to the non-netted, orange-fleshed melons of Europe, but today may refer to any orange-fleshed melon of the C. melo species,[2] including the netted muskmelon which is called cantaloupe in North America, rockmelon in Australia and New Zealand, and spanspek in Southern Africa. Cantaloupes range in mass from 0.5 to 5 kilograms (1 to 11 lb).

Etymology and origin

The name cantaloupe was derived in the 18th century via French cantaloup from The Cantus Region of Italian Cantalupo, which was formerly a papal county seat near Rome, after the fruit was introduced there from Armenia.[3] It was first mentioned in English literature in 1739.[2] The cantaloupe most likely originated in a region from South Asia to Africa.[2] It was later introduced to Europe, and around 1890, became a commercial crop in the United States.[2]

Melon derived from use in Old French as meloun during the 13th century, and from Medieval Latin melonem, a kind of pumpkin.[4] It was among the first plants to be domesticated and cultivated.[4]

The South African English name spanspek is said to be derived from Afrikaans Spaanse spek ('Spanish bacon'); supposedly, Sir Harry Smith, a 19th-century governor of Cape Colony, ate bacon and eggs for breakfast, while his Spanish-born wife Juana María de los Dolores de León Smith preferred cantaloupe, so South Africans nicknamed the eponymous fruit Spanish bacon.[5][6] However, the name appears to predate the Smiths and date to 18th-century Dutch Suriname: J. van Donselaar wrote in 1770, "Spaansch-spek is the name for the form that grows in Suriname which, because of its thick skin and little flesh, is less consumed."[7]

Types

Cantaloupe in cross-section | |

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 141 kJ (34 kcal) |

8.16 g | |

| Sugars | 7.86 g |

| Dietary fiber | 0.9 g |

0.19 g | |

0.84 g | |

| Vitamins | Quantity %DV† |

| Vitamin A equiv. | 21% 169 μg19% 2020 μg26 μg |

| Thiamine (B1) | 4% 0.041 mg |

| Riboflavin (B2) | 2% 0.019 mg |

| Niacin (B3) | 5% 0.734 mg |

| Pantothenic acid (B5) | 2% 0.105 mg |

| Vitamin B6 | 6% 0.072 mg |

| Folate (B9) | 5% 21 μg |

| Choline | 2% 7.6 mg |

| Vitamin C | 44% 36.7 mg |

| Vitamin K | 2% 2.5 μg |

| Minerals | Quantity %DV† |

| Calcium | 1% 9 mg |

| Iron | 2% 0.21 mg |

| Magnesium | 3% 12 mg |

| Manganese | 2% 0.041 mg |

| Phosphorus | 2% 15 mg |

| Potassium | 6% 267 mg |

| Sodium | 1% 16 mg |

| Zinc | 2% 0.18 mg |

| Other constituents | Quantity |

| Water | 90.2 g |

| |

| †Percentages are roughly approximated using US recommendations for adults. Source: USDA FoodData Central | |

The European cantaloupe or true cantaloupe, C. melo var. cantalupensis, is lightly ribbed with a sweet and flavorful flesh and a gray-green skin that looks quite different from that of the North American cantaloupe.[2]

The North American cantaloupe or muskmelon, C. melo var. reticulatus, common in the United States, Mexico, and some parts of Canada, is a different variety of C. melo, a melon with a reticulated ("net-like") peel.[2] It is a round melon with firm, orange, moderately sweet flesh.

Production

In 2016, global production of melons, including cantaloupes, totaled 31.2 million tons, with China accounting for 51% of the world total (15.9 million tons).[8] Other significant countries growing cantaloupe were Turkey, Iran, Egypt, and India producing 1 to 1.9 million tons, respectively.[8]

California grows 75% of the cantaloupes in the US.[9]

Uses

Culinary

Cantaloupe is normally eaten as a fresh fruit, as a salad, or as a dessert with ice cream or custard. Melon pieces wrapped in prosciutto are a familiar antipasto. The seeds are edible and may be dried for use as a snack.

Because the surface of a cantaloupe can contain harmful bacteria—in particular, Salmonella[10]—it is recommended that a melon be washed and scrubbed thoroughly before cutting and consumption to prevent risk of Salmonella or other bacterial pathogens.[11]

A moldy cantaloupe in a Peoria, Illinois, market in 1943 was found to contain the highest yielding strain of mold for penicillin production, after a worldwide search.[12][13]

Nutrition

Raw cantaloupe is 90% water, 8% carbohydrates, 0.8% protein and 0.2% fat, providing 140 kJ (34 kcal) and 2020 μg of the provitamin A orange carotenoid, beta-carotene per 100 grams. Fresh cantaloupe is a rich source (20% or more of the Daily Value, or DV) of vitamin C (44% DV) and vitamin A (21% DV), with other nutrients in negligible amounts (less than 10% DV) per 100 grams (see table).

See also

References

- ↑ Pitrat, Michel (2017). "Melon Genetic Resources: Phenotypic Diversity and Horticultural Taxonomy". In Grumet, Rebecca (ed.). Genetics and Genomics of Cucurbitaceae. Plant Genetics and Genomics: Crops and Models. Vol. 20. Cham: Springer International Publishing. pp. 25–60. doi:10.1007/7397_2016_10. ISBN 978-3-319-49332-9.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Marion Eugene Ensminger; Audrey H. Ensminger (1993). "Cantaloupe". Foods & Nutrition Encyclopedia (2nd Edition, Volume 1 ed.). CRC Press. pp. 329–331. ISBN 084938981X.

- ↑ "Cantaloupe". Oxford English Dictionary. 2016. Archived from the original on 28 July 2012. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- 1 2 "Melon". Online Etymology Dictionary, Douglas Harper Inc. 2019. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ↑ "How did spanspek get its name?". Food Lover's Market. 15 January 2018.

- ↑ Grahl, Bernd (18 December 2015). "How the cantaloupe melon received its name spanspek".

- ↑ "How spanspek got its South African name". www.fullstopcom.com. 19 October 2018.

- 1 2 "Production of melons, including cantaloupes for 2016 (Crops/world regions/production quantity from pick lists)". Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Statistics Division (FAOSTAT). 2017. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ↑ Werner, Erika; Reiley, Laura (27 August 2021). "California's 'Cantaloupe Center' struggles to reign supreme as drought pummels agriculture across the West". Washington Post. Retrieved 28 August 2021.

- ↑ Munnoch, S. A.; Ward, K.; Sheridan, S.; Fitzsimmons, G. J.; Shadbolt, C. T.; Piispanen, J. P.; Wang, Q.; Ward, T. J.; Worgan, T. L. M.; Oxenford, C.; Musto, J. A.; McAnulty, J.; Durrheim, D. N. (2009). "A multi-state outbreak of Salmonella Saintpaul in Australia associated with cantaloupe consumption". Epidemiology and Infection. 137 (3): 367–74. doi:10.1017/S0950268808000861. hdl:1959.13/39126. PMID 18559128. S2CID 206280340.

- ↑ "Kentucky: Cabinet for Health and Family Services – Salmonella2012". Archived from the original on 24 December 2014. Retrieved 18 August 2012.

In general, the FDA recommends thoroughly washing and scrubbing the rinds of all cantaloupes and melons prior to cutting and slicing, and to keep sliced melons refrigerated prior to eating.

- ↑ Bellis, Mary (30 June 2017). "The History of Penicillin: Alexander Fleming, John Sheehan, Andrew J Moyer". ThoughtCo. Archived from the original on 15 June 2011. Retrieved 9 July 2018.

- ↑ "Penicillin Timeline". United States Department of Agriculture Agricultural Research Service. 14 February 2018.

Then the Peoria researchers made yet another breakthrough. Searching for a superior strain of Penicillium, they found it on a moldy cantaloupe in a Peoria garbage can. When the new strain was made available to drug companies, production skyrocketed.

External links

Media related to Cucumis melo cantaloupe group at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Cucumis melo cantaloupe group at Wikimedia Commons- Sorting Cucumis names– Multilingual multiscript plant name database