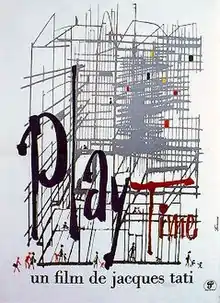

| Playtime | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Jacques Tati |

| Written by |

|

| Produced by | Bernard Maurice |

| Starring | Jacques Tati |

| Cinematography |

|

| Edited by | Gérard Pollicand |

| Music by | Francis Lemarque |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 124 minutes |

| Countries |

|

| Languages |

|

Playtime (stylized as PlayTime and also written as Play Time) is a 1967 comedy film directed by Jacques Tati. In the film, Tati again plays Monsieur Hulot, the popular character who had central roles in his earlier films Les Vacances de Monsieur Hulot (1953) and Mon Oncle (1958). However, Tati grew ambivalent towards playing Hulot as a recurring central role during production; he appears intermittently in Playtime, alternating between central and supporting roles.

Shot on 70 mm, the work is notable for its enormous set, which Tati had built specially for the film, as well as Tati's trademark use of subtle yet complex visual comedy supported by creative sound effects; dialogue is frequently reduced to the level of background noise.

Playtime is considered Tati's masterpiece and his most daring work. In 2022, Playtime was 23rd on the British Film Institute's critics' list and 41st in their directors' list of "Top 100 Greatest Films of All Time". The film was a financial failure upon release but is now widely regarded as one of the greatest films of all time.

Plot

Playtime is set in a futuristic, hyperconsumerist Paris. The story is structured in six sequences, linked by two characters who repeatedly encounter one another over the course of a day: Barbara, a young American tourist visiting Paris with an American tourist group, and Monsieur Hulot, a befuddled Frenchman lost in the new modernity of Paris. The sequences are as follows:

- The Airport: The American tour group arrives at the ultra-modern and impersonal Orly Airport.

- The Offices: M. Hulot arrives at one of the glass and steel buildings for an important meeting but gets lost in a maze of disguised rooms and offices, eventually stumbling into a trade exhibition of lookalike business office designs and furniture nearly identical to those in the rest of the building.

- The Trade Exhibition: M. Hulot and the American tourists are introduced to the latest modern gadgets, including a door that slams "in golden silence" and a broom with headlights, while the Paris of legend goes all but unnoticed save for a flower seller's stall and a single reflection of the Eiffel Tower in a glass door. Later, a similar reflection shows the Arc de Triomphe.

- The Apartments: As night falls, M. Hulot meets with an old friend who invites him to his sparsely furnished, ultra-modern and glass-fronted flat. This sequence is filmed entirely from the street, observing M. Hulot and other building residents through uncurtained floor-to-ceiling picture windows.

- The Royal Garden: This sequence takes up almost the entire second half of the film. At the restaurant, M. Hulot reunites with several characters he has periodically encountered during the day, along with a few new ones, including a nostalgic ballad singer and a boisterous American businessman.

- The Carousel of Cars: M. Hulot buys Barbara two small gifts as mementos of Paris before her departure. In the midst of a complex ballet of cars in a traffic circle, the tourists' bus returns to the airport.

Cast

When possible, Tati cast nonprofessionals. He wanted people whose inner essence matched their characters and who could move in the way he wanted.

- Jacques Tati as Monsieur Hulot

- Barbara Dennek as Barbara, a young American tourist

- Rita Maiden as Mr. Schultz's companion

- France Rumilly as a seller of eyeglasses

- France Delahalle as a customer at the department store

- Valérie Camille as Mr. Lacs's secretary

- Erica Dentzler as Mrs. Giffard

- Nicole Ray as the nostalgic ballad singer

- Yvette Ducreux as a coat check girl

- Nathalie Jem as a customer at Royal Garden

- Jacqueline Lecomte as Barbara's travel companion

- Olivia Poli as a customer at Royal Garden

- Alice Field as a customer at Royal Garden

- Sophie Wennek as a tour guide

- Evy Cavallaro as a customer at Royal Garden

- Laure Paillette as 1st lady at the lamppost

- Colette Proust as 2nd lady at the lamppost

- Luce Bonifassy as a customer at Royal Garden

- Ketty France as a customer at Royal Garden

- Eliane Firmin-Didot as a customer at Royal Garden

- Billy Kearns as Mr. Schulz, the American businessman

- Tony Andal as the doorman at Royal Garden

- Yves Barsacq as Mr. Hulot's old acquaintance

- André Fouché as the Royal Garden manager

- Georges Montant as Mr. Giffard

- John Abbey as Mr. Lacs

- Reinhard Kolldehoff as the German director

- Michel Francini as the head waiter

- Grégoire Katz as the German salesman

- Jack Gauthier as the guide

- Henri Piccoli as an important man

- Léon Doyen as the old doorman

- François Viaur as a waiter at Royal Garden

- Marc Monjou as the false Mr. Hulot

Production

The film is famous for its enormous, specially constructed set and background stage, known as "Tativille", which contributed significantly to the film's large budget, said to be 17 million francs (which would have been roughly 3.4 million US dollars in 1964). The set required a hundred workers to construct along with its own power plant. Budget crises and other disasters stretched the shooting schedule to three years, including 1.4 million francs in repairs after the set was damaged by storms.[3] Tati observed that the cost of building the set was no greater than what it would have cost to have hired Elizabeth Taylor or Sophia Loren for the leading role.[3] Budget overruns forced Tati to take out large loans and personal overdrafts to cover ever-increasing production costs.

As Playtime depended greatly on visual comedy and sound effects, Tati chose to shoot the film using high-resolution 70 mm film, and a stereophonic soundtrack that was complex for its time.

To save money, some of the building facades and the interior of the Orly set were actually giant photographs. (The photographs also had the advantage of not reflecting the camera or lights.) The Paris landmarks Barbara sees reflected in the glass door are also photographs. Tati also used life-sized cutout photographs of people to save money on extras. These cutouts are noticeable in some of the cubicles when Hulot overlooks the maze of offices, and in the deep background in some of the shots at ground level from one office building to another.

Style

Tati wanted the film to be in color but look like it was filmed in black and white – an effect he had previously employed to some extent in Mon Oncle. The predominant colors are shades of grey, blue, black, and greyish white. Green and red are used as occasional accent colors: for example, the greenish hue of patrons lit by a neon sign in a sterile and modern lunch counter, or the flashing red light on an office intercom. It has been said that Tati had one red item in every shot.

Except for a single flower stall, there are no genuine green plants or trees on the set, though dull plastic plants adorn the outer balconies of some buildings, including the restaurant (the one location shot apart from the road to the airport). Thus, when the character of Barbara arrives at the Royal Garden restaurant in an emerald green dress seen as "dated" by the other whispering female patrons clothed in dark attire, she visually contrasts not only with the other diners, but also with the entire physical environment of the film. As the characters in the restaurant scene begin to lose their normal social inhibitions and revel in the unraveling of their surroundings, Tati intensifies both color and lighting accordingly: late arrivals to the restaurant are less conservative, arriving in vibrant, often patterned clothing.

Tati detested close-ups, considering them crude, and shot in 65 mm film[4] so that all the actors and their physical movements would be visible, even when they were in the far background of a group scene. He used sound rather than visual cues to direct the audience's attention; with the large image size, sound could be both high and low in the image as well as left and right.[5] As with most Tati films, sound effects were utilized to intensify comedic effect; Leonard Maltin wrote that Tati was the "only man in movie history to get a laugh out of the hum of a neon sign!"[6] Almost the entire film was dubbed after shooting; the editing process took nine months.

Philip Kemp has described the film's plot as exploring "how the curve comes to reassert itself over the straight line".[5] This progression is carried out in numerous ways. At the beginning of the film, people walk in straight lines and turn on right angles. Only working-class construction workers (representing Hulot's "old Paris", celebrated in Mon Oncle) and two music-loving teenagers move in a curvaceous and naturally human way. Some of this robot-like behavior begins to loosen in the restaurant scene near the end of the film, as the participants set aside their assigned roles and learn to enjoy themselves after a plague of opening-night disasters.

Throughout the film, the American tourists are continually lined up and counted, though Barbara keeps escaping and must be frequently called back to conform with the others. By the end, she has united the curve and the line (Hulot's gift, a square scarf, is fitted to her round head); her straight bus ride back to the airport becomes lost in a seemingly endless traffic circle that has the atmosphere of a carnival ride.

The extended apartment sequence, where Tati's character visits a friend and tours his apartment, is notable. Tati keeps his audience outside of the apartment as we look inside the lives of these characters. In September 2012, Interiors, an online journal that is concerned with the relationship between architecture and film, released an issue that discussed how space is used in this scene. The issue highlights how Tati uses the space of the apartment to create voyeurs out of his audience.[7]

Reception

On its original French release, Playtime was commercially unsuccessful, failing to earn back a significant portion of its production costs. The film was entered into the 6th Moscow International Film Festival, where it won a Silver Prize.[8]

Results were the same upon the film's eventual release in the United States in 1973 (even though it had finally been converted to a 35 mm format at the insistence of US distributors and edited down to 103 minutes). Though Vincent Canby of The New York Times called Playtime "Tati's most brilliant film", it was no more a commercial success in the US than in France. Debts incurred as a result of the film's cost overruns eventually forced Tati to file for bankruptcy.

Playtime is regarded as a great achievement by many critics. On the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds an approval rating of 98% based on 54 reviews, with an average rating of 8.9/10. The website's critics consensus reads, "A remarkable achievement, Playtime packs every scene with sight gags and characters that both celebrates and satirizes the urbanization of modern life."[9]

Notes

References

- ↑ "PlayTime de Jacques Tati (1967)". UniFrance. Retrieved 2 May 2023.

- ↑ "Play Time – Tempo di divertimento". Cinematografo (in Italian). Retrieved 2 May 2023.

- 1 2 Bellos, David (2001). Jacques Tati: His Life and Art. London: Harvill Press. pp. 293–294. ISBN 978-1-8604-6924-4.

- ↑ Rosenbaum, Jonathan (18 August 2009). "The Dance of Playtime". The Criterion Collection. Retrieved 17 October 2022.

- 1 2 Kemp, Philip (2010). Playtime (DVD). BFI Video Publishing.

- ↑ Reichert, Jeff (27 June 2010), "Monsieur Hulot's Holiday", Reverse Shot, Museum of the Moving Image

- ↑ Ahi, Mehruss Jon; Karaoghlanian, Armen (September 2012). "Playtime". Interiors. Retrieved 11 July 2018 – via Issuu.

- ↑ "1969 year". Moscow International Film Festival. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- ↑ "Playtime". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 2 May 2023.

External links

- Playtime at IMDb

- Playtime at AllMovie

- Playtime at the TCM Movie Database

- PlayTime – a video essay by David Cairns at The Criterion Collection

- Review of the 2006 Criterion DVD, and comparison with the 2001 version on DVD Talk

- My holiday with Monsieur Hulot (The Guardian, 2003)