The Plum Island Eagle Sanctuary (Plum Island) is a 52-acre island in the Illinois River owned by the Illinois Audubon Society.[1] It was purchased March 24, 2004 to act as a wildlife sanctuary,[1] to protect foraging habitat for wintering bald eagles.[2] It is close to Matthiessen State Park and adjacent to Starved Rock State Park.

History

Remains found on Plum Island date to around 2000 BC.[3] The large number of human remains of the island have led to it being called "Massacre Island"; another former name is Wooded Island.[4]

In 1950, the park acquired a state charter to use the island as an airstrip known as Starved Rock Airpark.[5] A cable car shuttled visitors from the park to the island, where they could go on a plane ride for a fee. Severe flooding destroyed the cable car infrastructure in 1970. Plane rides stopped being offered in 1975, with the airstrip finally closing just before 1980.[6]

When purchased in 2002, it had been slated by developers for development of fifty high-priced homes, and fully half of the island would have been bulldozed, destroying both bald eagle habitat and Native American burial sites.[7] Audubon Society and its supporters successfully prevented Plum Island from being developed into a resort area and upscale condominiums. The group of supporters who accomplished this was led by the Illinois Audubon Society with substantial support from Friends of Plum Island, Midwest SOARRING Foundation, Starved Rock Audubon Society, Eagle Nature Foundation, Save Our American Raptors, the Sierra Club of Illinois, and then Illinois Lt. Governor (later Governor) Pat Quinn.

Funds to purchase the island were provided by a grant from the Illinois Clean Energy Community Foundation. The Trust For Public Land also assisted with the purchase by negotiating with the developers and other legal aspects.

After acquiring the island, the Illinois Audubon Society gained the support of Living Lands and Waters, a river cleanup group led by Chad Pregracke. LL&W removed unsightly buildings and structures from the island during a month-long effort, hauling away the debris on their barge.

The Illinois Environmental Protection Agency provided a small grant to help fund removal of debris, old cabins and a boat from the island.[8]

The island is closed to the public, except for restoration activities.[9] The Illinois Audubon Society wanted to save the island for the eagles, to preserve the scenic view from Starved Rock, and to protect the Native American archaeological sites which are there.[9]

Eagle releases

The first release of rehabilitated eagles at the sanctuary occurred on November 12, 2011.[10][1] Two juvenile bald eagles were rescued on June 2, 2011 after their nest fell 85 feet in a windstorm at the Mooseheart facility near Batavia, Illinois. They were rescued and raised by the Flint Creek Wildlife Rehabilitation organization and were released back to the wild at Plum Island to blend with the current eagle population.[10][1]

Archaeological site

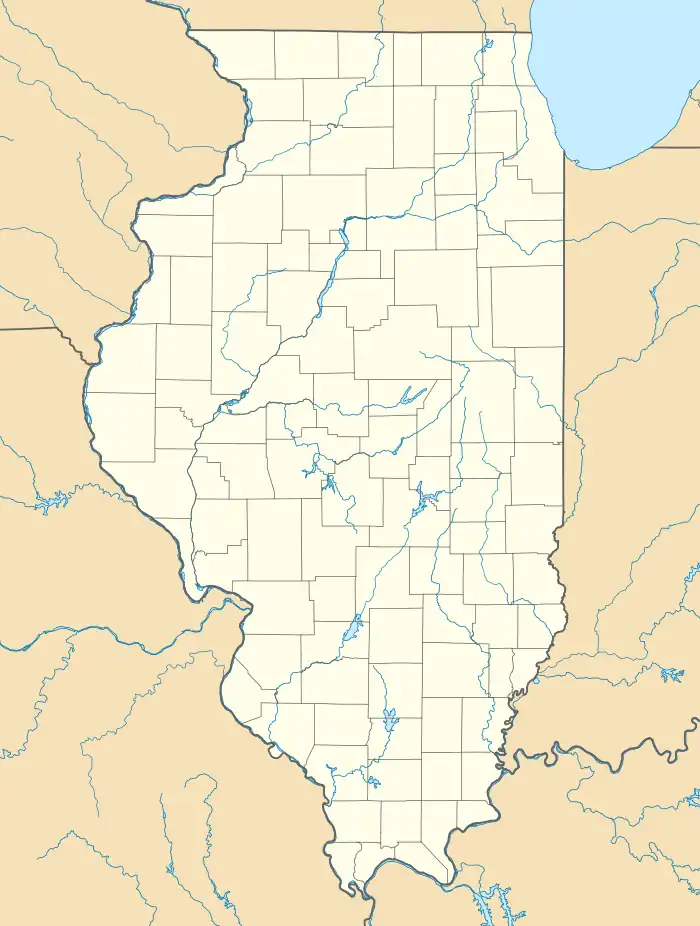

| Plum Island Site | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | on the Illinois River in LaSalle County, Illinois |

| Coordinates | 41°19′17″N 88°59′25″W / 41.32139°N 88.99028°W |

| Area | 3 acres |

Location in Illinois  Location in United States | |

The Plum Island Site (Ls-2) is located in the Illinois River near Starved Rock, LaSalle County, Illinois, in the vicinity of the Hotel Plaza site and the Zimmerman site (aka Grand Village of the Illinois). It is a multi-component site representing prehistoric, Protohistoric and early Historic periods, with the main occupation being a late Prehistoric to early Historic component with Upper Mississippian affiliation.[11]

History of archaeological investigations

Excavations took place in 1930 under the auspices of the University of Illinois and overseen by Arthur Randolph Kelly. A total of 7,316 artifacts was collected, but the site report was not done until 1964 when Gloria Fenner of the University of Illinois did a Master's Thesis and followed it up with an article in the Illinois Archaeological Survey. Unfortunately, in the interim between excavation and the report, many of the artifacts were misplaced and some stratigraphic information was lost.[11]

Results of data analysis

Excavations at the site yielded prehistoric and Historic artifacts, pit features, burials, animal bone and plant remains.[11]

Several prehistoric and Historic components were identified at the site:[11]

- Prehistoric Early Woodland Component - c. B.C. 1500 - B.C. 200; characterized by the earliest pottery made in the Great Lakes region; Marion Thick and Morton Incised

- Prehistoric Middle Woodland Component - c. B.C. 200 - A.D. 500; characterized by Havana Ware and other types

- Prehistoric to early Historic Upper Mississippian Component - c. A.D. 1500 - A.D. 1600s; characterized by Fisher and Langford Ware pottery and European trade goods

There were no house structures noted at the site. However, the entire site was honeycombed with pit features, totaling 470, some of them overlapping. Three types were recognized: refuse pits, firepits and “unidentified” or uncategorized. Up to fourteen burials were also excavated, with 4 of them having grave goods.[11]

The refuse pits were thought to have first been storage pits that were converted into refuse pits once their contents began to sour. They contained animal bone, charcoal and artifacts.[11]

The firepits appear to correspond to what has ethnographically been described as “macoupin roasting pits” by the early French explorers Deliette and LaSalle and described from the Zimmerman site.[11][12] The macoupins are apparently tubers from a species of water lily, perhaps the American Lotus (Nelumbo lutea).[12] Tubers of Nelumbo lutea have been recovered from similar roasting pits at the Elam[13] and Schwerdt[14][15] sites on the Kalamazoo River in western Michigan; and tubers of the white water lily (Nymphaea tuberosa) have been recovered from roasting pits at the Griesmer site in northwestern Indiana.[16] This particular cooking technique may have been used prehistorically for several species of similar water lilies, or other similar root plants. No tubers were specifically recovered from the Plum Island site, however. This may be due to the fact that there was no systematic effort by the excavators to collect plant remains.

Human Remains

Fourteen possible burials were investigated during the 1930 excavation. Several burials were found at depths of less than 1.5 feet (0.46 m), with at least two burials in pits between 3 feet (0.91 m) and 5.25 feet (1.60 m). The original field notes are described by Fenner as "confused". She proposes that 8 burials were excavated. In addition to these burials, Kelly notes the following in his 1930 field notes.

"Grim reminiscences of the destruction of the Illinois Indian town and the massacre of some of the inhabitants on the spot were uncovered in the first year of exploration, in the form of charred wood and unburied skeletons strewn about on the old site of the village just a few inches below the present surface of the plowed field."

Arthur Randolph Kelly, 1930 field notes[17]

No photographs or detailed descriptions of these remains were present in the assemblage of data from the 1930 excavation[11]

Animal Remains

Remains from a wide variety of species were recovered from the site. The main species present were fish (especially channel catfish and freshwater drum), deer, elk, raccoon, beaver, dog, turtle, snails and fresh water mussels. In addition, bison, mink and bobcat were recovered in smaller amounts.[11] These remains were not modified into tools like the bone tools described in the Artifacts section below, and may be considered food remains or, in the case of the dog, the remains of ceremonial activities. Dog sacrifice and dog meat consumption was observed to have ceremonial and religious implications in early Native American tribes.[18][19]

Plant Remains

Plant remains were not systematically collected via the flotation technique as that did not become standard archaeological practice until the 1970s. The excavators did however recover maize in the form of kernels and corncobs. The maize was an earlier type than that found at the Zimmerman site.[11]

Pottery Artifacts

Archaeologists often find pottery to be a very useful tool in analyzing a prehistoric culture. It is usually very plentiful at a site and the details of manufacture and decoration are very sensitive indicators of time, space and culture.[20]

No whole or completely reconstructable vessels were found at the site. Therefore, the researchers looked primarily at rim sherds and distinctive body sherds to analyze the pottery.

Early Occupations

The Early and Middle Woodland periods are represented by a small scattering of pottery at Plum Island. The Early Woodland is represented by Marion Thick, the first pottery ever made in this part of North America, and traces of a few other early types. The Middle Woodland is represented by Havana Ware and Naples Ware, among others.[11] The Havana Culture was thought to be a local variant of the more prominent Middle Woodland cultures such as the Adena and Hopewell cultures of the Mississippi and Ohio River Valleys. Middle Woodland cultures are characterized by their large burial mounds, some of which are still visible today; as well as their distinctive pottery forms, ceremonial practices, agricultural activities, and widespread trade networks.[21]

Upper Mississippian Component

A total of 6,989 sherds were collected from the site, of which 6,838 were assigned to the Upper Mississippian component at Plum Island.[11]

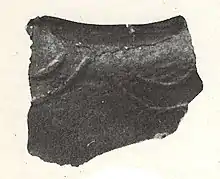

Two types of pottery were found within this component; shell tempered Fisher ware and grit-tempered Langford ware (which is grit-tempered).[11]

Fisher Ware was first described at the Fisher Mound site in northeastern Illinois near the mouth of the Illinois River.[22][12][23] It has also been noted at the Anker[24] and Hoxie Farm[25] sites near Chicago, Illinois.

This pottery is characterized by shell tempered, globular vessels with cordmarked surfaces and straight to excurved rim profile. Decoration, when present, consists of trailed or incised decoration forming arches and festoons, often combined with punctates. Notched lips and rim lugs are also common.[11][12][23]

Three types of Fisher ware were reported:[11]

- Fisher Plain (106 sherds) - characterized by plain finish with no decoration

- Fisher Cordmarked (160 sherds) - characterized by cordmarked finish with no decoration

- Fisher Trailed (72 sherds) - characterized by incised and trailed lines, forming arches and festoons

Langford Ware was also first reported at the Fisher site, and has also been found at the nearby Zimmerman and Gentleman Farm sites. It is a grit-tempered ware usually with smoothed surface. Decoration, when present, consists of incised and trailed lines, punctates and finger impressions, combined to form arches and festoons. Rim profile is excurved and sometimes collared. Lugs and loop handles are present on some vessels and nodes are also sometimes present.[11][12][23]

The following types of Langford Ware were reported:[11]

- Langford Plain (5,519 sherds) - smooth surface with no decoration

- Langford Trailed (630 sherds) - decorated sherds

- Langford Collared (44 sherds) - rims with collars present

- Langford Noded (2 sherds) - vessels with row of nodes around shoulder

- Langford Plain/Thick (61 sherds) - sherds >0.9mm thick

Other Artifacts

Non-pottery artifacts recovered from the site included:[11]

- 98 bone artifacts and pieces of worked bone including bone and antler beamers, counters, scrapers, awls, antler projectile points, a cut and incised fish gill cover, a harpoon, and many other specimens of worked bone that do not fit neatly into a recognizable category.

- 82 chipped stone artifacts - including projectile points, scrapers (subdivided into variants based on manufacturing technique), knives and drills. Of the projectile points, the most numerous category of tools was the small triangular point, or Madison point.

- 20 ground stone artifacts - including hammerstones, celts, grinding stones, a plummet, an axe and an adze fragment.

- 5 European trade goods - including one bead, brass tinkling cones, an iron knife blade and a copper fragment.

The non-pottery artifacts found at an archaeological site can provide useful cultural context as well as a glimpse into the domestic tasks performed at a site; ceremonial or religious activities; recreational activities; and clothing or personal adornment.[26]

Some of the most prominent and diagnostic non-pottery artifacts are presented here in more detail:

| Material | Description | Image | Qty | Function / use | Comments / associations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chipped stone | Small triangular points (aka Madison point) |  |

3 | Hunting/fishing/warfare | Also known as “arrowheads”; are thought to be arrow-tips for bows-and-arrows. The usage of the bow-and-arrow seems to have greatly increased after A.D. 1000, probably as a result of increased conflict.[21][27] |

| Bone | Game counter |  |

1 | Entertainment function | These have been found at Fisher, Huber, Langford and Oneota (especially Grand River focus and Lake Winnebago focus) sites and may have been used in a gambling game.[16] Gambling was noted to be a popular pastime among the early Native American tribes.[19][18] |

| Bone | Harpoon |  |

1 | Fishing function | Similar harpoons made of bone or antler have been recovered from other Upper Mississippian sites in the Midwest, including Fisher, Fifield and Oak Forest.[22][16][11][28][29] |

| Bone | Beamer |  |

1 | Domestic function / de-hairing hides | Commonly found at Upper Mississippian sites in northern Illinois[16] |

Significance

The Plum Island site reflects a series of occupations going back thousands of years, but the main occupation consists of a late prehistoric Upper Mississippian component. This component apparently lasts until the Protohistoric or early Historic period based on the European trade goods present at the site.[11]

No house structures were present at the site, but the presence of numerous pit features indicates intensive occupation took place, possibly to harvest and roast plants like macoupins in the fire pits. Very little bison bone was found in the food remains, possibly because bison were not present until after A.D. 1600 in most of Illinois.[11][23]

The trait list of Plum Island was compared to that of other sites in Illinois to gauge regional relationships in material culture. It was found that Plum Island shared 79% of traits with the Heally Component at the Zimmerman site; 75% with the Fisher Period B; and 67% with the Gentleman Farm site. The trait lists combined all attributes including pottery, other artifacts, features, plant remains and animal remains.[11]

References

- 1 2 3 4 Eaglets heading back into the wild Linda Girardi, (Chicago) Sun-Times Media. Publishing instance: The Naperville Sun, October 23, 2011 P17

- ↑ "Eagle Habitat on Illinois River Protected". Archived from the original on 2007-07-13. Retrieved 2011-02-12.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ↑ Illinois Archaeological Survey (1 January 1963). "Reports on Illinois prehistory: I." University of Illinois – via Google Books.

- ↑ Koller, Susan Shaver (2006). LaSalle County. Arcadia Publishing. p. 33. ISBN 0738541052. Retrieved February 21, 2019 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Niemi, Ryan. "Starved Rock Airpark, IL". TopoQuest. Retrieved February 21, 2019.

- ↑ Niemi, Ryan. "Abandoned & Little-Known Airfields: Northern Illinois". TopoQuest. Retrieved February 21, 2019.

- ↑ http://www.illinois.gov/PressReleases/ShowPressRelease.cfm?SubjectID=1&RecNum=2875 Victory Rally to celebrate saving Plum Island from developers March 28, 2004 access date 2011-02-12

- ↑ ILLINOIS EPA CONTRIBUTES FUNDING TO PLUM ISLAND CLEANUP EFFORTS, Illinois Environmental Protection Agency press release, October 15, 2004

- 1 2 "Plum Island Eagle Sanctuary". Illinois Audubon Society. Retrieved February 21, 2019.

- 1 2 Eaglets Rescued at Mooseheart Released at Starved Rock, Marie Wilson, (Chicago) Daily Herald. Publishing instance: The Daily Herald, November 13, 2011

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 Fenner, Gloria J. (1963). Blumn, Elaine A. (ed.). The Plum Island Site, LaSalle County, Illinois. Urbana, Illinois: Illinois Archaeological Survey, Bulletin No. 4. pp. 1–105.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Brown, James A., ed. (1961). The Zimmerman Site: A Report on Excavations at the Grand Village of Kaskaskia. Springfield, Illinois: Illinois State Museum, Report of Investigations No. 9.

- ↑ DeRoo, Brian (1991). Flotation Data Sampling Strategies in Archaeobotanical Research: An Experiment at the Elam Site (20AE195), Allegan County, Michigan (Masters thesis). Kalamazoo: Western Michigan University. p. 23.

- ↑ Cremin, William M. (1980). "The Schwerdt Site: A Fifteenth Century Fishing Station on the Lower Kalamazoo River, Southwest Michigan". The Wisconsin Archaeologist. 61: 280–292.

- ↑ Cremin, William M. (1983). "Late Prehistoric Adaptive Strategies on the Northern Periphery of the Carolinian Biotic Province: A Case Study from Southwest Michigan". Midcontinental Journal of Archaeology. 8: 91–107.

- 1 2 3 4 Faulkner, Charles H. (1972). "The Late Prehistoric Occupation of Northwestern Indiana: A Study of the Upper Mississippi Cultures of the Kankakee Valley". Prehistory Research Series. V (1): 1–222.

- ↑ Blue Book of the State of Illinois 1931-1932. Chicago: Illinois Secretary of State. 1932. p. 321.

- 1 2 Kinietz, W. Vernon (1940). The Indians of the Western Great Lakes 1615-1760 (1991 ed.). Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press.

- 1 2 Blair, Emma Helen (1911). The Indian Tribes of the Upper Mississippi Valley and Region of the Great Lakes (1996 ed.). Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press.

- ↑ Shepard, Anna O. (1954). Ceramics for the Archaeologist. Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Institute of Washington, Publication 609.

- 1 2 Mason, Ronald J. (1981). Great Lakes Archaeology. New York, New York: Academic Press, Incl.

- 1 2 Griffin, James A. (1943). The Fort Ancient Aspect: Its Cultural and Chronological Position in Mississippi Valley Archaeology (1966 ed.). Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Museum of Anthropology.

- 1 2 3 4 Brown, Margaret Kimball (1975). The Zimmerman Site: Further Excavations at the Grand Village of the Kaskaskia. Springfield, Illinois: Illinois State Museum, Report of Investigations No. 32.

- ↑ Bluhm, Elaine A.; Liss, Allen (1961). "Chapter IX: The Anker Site". In Bluhm, Elaine A. (ed.). Chicago Area Archaeology. Urbana, Illinois: Illinois Archaeological Survey, Bulletin No. 3.

- ↑ Herold, Elaine Bluhm; O'Brien, Patricia J.; Wenner, David J. Jr. (1990). Brown, James A.; O'Brien, Patricia J. (eds.). Hoxie Farm and Huber: Two Upper Mississippian Archaeological Sites in Cook County, Illinois, IN At The Edge of Prehistory: Huber Phase Archaeology in the Chicago Area. Kampsville, Illinois: Center for American Archaeology.

- ↑ Bettarel, Robert Louis; Smith, Hale G. (1973). The Moccasin Bluff Site and the Woodland Cultures of Southwest Michigan. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Museum of Anthropology, Anthropological Papers No. 49.

- ↑ Lepper, Bradley T. (2005). Ohio Archaeology (4th ed.). Wilmington, Ohio: Orange Frazer Press.

- ↑ Brown, James A. (1990). Brown, James A.; O'Brien, Patricia J. (eds.). The Oak Forest Site: Investigations into Oneota Subsistence-Settlement in the Cal-Sag Area of Cook County, Illinois, IN At the Edge of Prehistory: Huber Phase Archaeology in the Chicago Area. Kampsville, Illinois: Center for American Archaeology.

- ↑ Bluhm, Elaine A.; Fenner, Gloria J. (1961). The Oak Forest Site, IN Chicago Area Archaeology. University of Illinois, Urbana, Illinois: Illinois Archaeological Survey Bulletin No. 3.

Further reading

- Gloria J. Fenner (1963), Elaine A. Bluhm (ed.), "The Plum Island Site, LaSalle County, Illinois", Reports on Illinois Prehistory I (Illinois Archaeological Survey, Bulletin 4): 1–105

External links

- Illinois Audubon Society: http://www.illinoisaudubon.org/LANDCONSERVATION/PlumIsland.html