In modern plumbing, a drain-waste-vent (or DWV) is a system that allows air to enter the plumbing system to maintain proper air pressure to enable the removal of sewage and greywater from a dwelling. Drain refers to water produced at fixtures such as sinks, and showers; waste refers to water from toilets. As the water runs down, proper venting is required to allow water to flow freely, and avoid a vacuum from being created. As the water runs down air must be allowed into the waste pipe either through a roof vent (external), or an internal vent.

Overview

DWV systems maintain neutral air pressure in the drains, allowing free flow of water and sewage down drains and through waste pipes by gravity. It is critical that a sufficient downward slope be maintained throughout the drain pipes, to keep liquids and entrained solids flowing freely towards the main drain from the building. In some situations, a downward slope out of a building to the sewer cannot be created, and a special collection pit and grinding lift "sewage ejector" pump are needed. By contrast, potable water supply systems operate under pressure to distribute water up through buildings, and do not require a continuous downward slope in their piping.

Every fixture is required to have an internal or external trap; double trapping is prohibited by plumbing codes due to its susceptibility to clogging. Every plumbing fixture must also have an attached vent. Without a vent, negative pressure from water leaving the system can cause a siphon which empties the trap. The top of stacks must be vented too, via a stack vent, which is sometimes called a stink pipe.[1]

All plumbing waste fixtures use traps to prevent sewer gases from leaking into the house. Through traps, all fixtures are connected to waste lines, which in turn take the waste to a "soil stack", also known as "soil stack pipe", "soil vent pipe" or "main". The drain-waste vent is attached at the building drain system's highest point, and rises (usually inside a wall) to and out of the roof. Waste exits from the building through the building's main drain and flows through a sewage line, which leads to a septic system or a public sewer. Cesspits are generally prohibited in developed areas. In the US, fixtures must have a vent (discharging into the "main stack" is not viewed as enough).[2]

The venting system, or plumbing vents, consists of a number of pipes leading from waste pipes to the outdoors, usually through the roof. Vents provide a means to release sewer gases outside instead of inside the house. Vents also admit oxygen to the waste system to allow aerobic sewage digestion, and to discourage noxious anaerobic decomposition. Vents provide a way to equalize the pressure on both sides of a trap, thereby allowing the trap to hold the water which is needed to maintain effectiveness of the trap, and avoiding "trap suckout" which otherwise might occur.

Operation

A sewer pipe is normally at neutral air pressure compared to the surrounding atmosphere. When a column of waste water flows through a pipe, it compresses air ahead of it in the pipe, creating a positive pressure that must be released so it does not push back on the waste stream and downstream trap water seals. As the column of water passes, air must freely flow in behind the waste stream, or negative pressure results. The extent of these pressure fluctuations is determined by the fluid volume of the waste discharge.

Excessive negative air pressure, behind a "slug" of water that is draining, can siphon water from traps at plumbing fixtures. Generally, a toilet outlet has the shortest trap seal, making it most vulnerable to being emptied by induced siphonage. An empty trap can allow noxious sewer gases to enter a building.

On the other hand, if the air pressure within the drain becomes suddenly higher than ambient, this positive transient could cause waste water to be pushed into the fixture, breaking the trap seal, with serious hygiene and health consequences if too forceful. Tall buildings of three or more stories are particularly susceptible to this problem. Vent stacks are installed in parallel to waste stacks to allow proper venting in tall buildings and eliminate these problems.

External venting

Most residential building drainage systems in North America are vented directly through the building roofs. The DWV pipe is typically ABS or PVC DWV-rated plastic pipe equipped with a flashing at the roof penetration to prevent rainwater from entering the buildings. Older homes may use asbestos,[3] copper, iron, lead or clay pipes, in rough order of increasing antiquity.

Under many older building codes, a vent stack (a pipe leading to the main roof vent) is required to be within approx. a 5-foot (1.5 m) radius of the draining fixture it serves (sink, toilet, shower stall, etc.)[4]. To allow only one vent stack, and thus one roof penetration as permitted by local building code, sub-vents may be tied together inside the building and exit via a common vent stack, frequently the "main" vent. One additional requirement for a vent stack connection occurs when there are very long horizontal drain runs with very little slope to the run. Adding a vent connection within the run will aid flow, and when used with a cleanout allows for better serviceability of the long run.

A blocked vent is a relatively common problem caused by anything from leaves, to dead animals, to ice dams in very cold weather, or a horizontal section of the venting system, sloped the wrong way and filled with water from rain or condensation. Symptoms range from bubbles in the toilet bowl when it is flushed, to slow drainage, and all the way to siphoned (empty) traps which allow sewer gases to enter the building.

When a fixture trap is venting properly, a "sucking" sound can often be heard as the fixture vigorously empties out during normal operation. This phenomenon is harmless, and is different from "trap suckout" induced by pressure variations caused by wastewater movement elsewhere in the system, which is not supposed to allow interactions from one fixture to another. Toilets are a special case, since they are usually designed to self-siphon to ensure complete evacuation of their contents; they are then automatically refilled by a special valve mechanism.

Internal venting

Mechanical vents (also called cheater vents[5]) come in two types: Air admittance valves and check vents, the latter being a vent with a check valve.

Air admittance valves (AAVs, or commonly referred to in the UK as Durgo valves and in the US as Studor vents and Sure-Vent®) are negative-pressure-activated, one-way mechanical valves, used in a plumbing or drainage venting system to eliminate the need for conventional pipe venting and roof penetrations. A discharge of wastewater causes the AAV to open, releasing the vacuum and allowing air to enter the plumbing vent pipe for proper pressure equalization.

Since AAVs will only operate under negative pressure situations, they are not suitable for all venting applications, such as venting a sump, where positive pressures are created when the sump fills. Also, where positive drainage pressures are found in larger buildings or multi-story buildings, an air admittance valve could be used in conjunction with a positive pressure reduction device such as the PAPA positive air pressure attenuator to provide a complete venting solution for more complicated drainage venting systems.

Using AAVs can significantly reduce the amount of venting materials needed in a plumbing system, increase plumbing labor efficiency, allow greater flexibility in the layout of plumbing fixtures, and reduce long-term roof maintenance problems associated with conventional vent stack roofing penetrations.

While some state and local building departments prohibit AAVs, the International Residential and International Plumbing Codes allow it to be used in place of a vent through the roof. AAVs are certified to reliably open and close a minimum of 500,000 times, (approximately 30 years of use) with no release of sewer gas; some manufacturers claim their units are tested for up to 1.5 million cycles, or at least 80 years of use. AAVs have been effectively used in Europe for more than two decades.

Island fixture vent

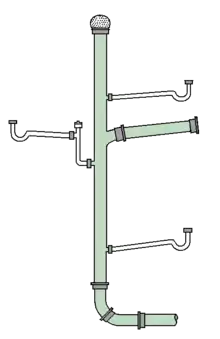

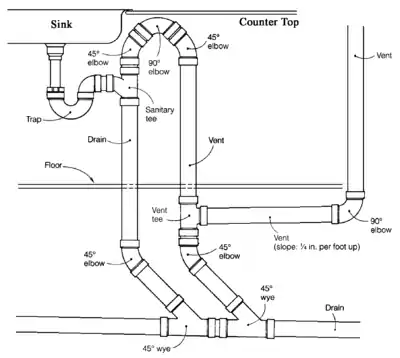

An island fixture vent, sometimes colloquially called a "Chicago Loop", "Boston loop" or "Bow Vent", is an alternate way of venting the trap installed on an under counter island sink or other similar applications where a conventional vertical vent stack or air admittance valve is not feasible or allowed.

As with all drains, ventilation must be provided to allow the flowing waste water to displace the sewer gas in the drain, and then to allow air (or some other fluid) to fill the vacuum which would otherwise form as the water flows down the pipe.

An island fixture vent provides an elegant solution for this necessity: when the drain is opened, water displaces the sewer gas up to the sanitary tee, the water flows downward while sewer gas is displaced upward and toward the vent. The vent can also provide air to fill any vacuum created.

The key to a functional island fixture vent is that the top elbow must be at least as high as the "flood level" (the peak possible drain water level in the sink). This is to ensure that the vent does not become a de facto drain should the actual drain get clogged.

Cost

The cost of installation is high because of the number of elbows and small pieces of pipe required. The largest cost outlay with modern plastic drain pipes is labor. Use of street elbows is helpful.

Alternately if moving sink to an island sink, install the P-trap below the floor of the island and vent off the top of the drain. Attach toward the trap and reverse 180 degrees so any water in the vent flows down the drain. Slope drain down, slope vent up, and attach to existing vent from previous existing fixture that is now abandoned. Patch previously existing drain to become vent. In Canada, the national plumbing code requires that the minimum trap arm be at least 2 times the pipe diameter, (e.g., 1.25 inch pipe needs a 2.5-inch trap arm, 1.5 pipe needs a 3-inch trap arm, etc.) and that the vent pipe be one size larger than the drain that it serves, also a cleanout is required on both the vent and the drain. The reason for this is in the event of a plugged sink, the waste water will back up and go down the vent, possibly plugging the vent (as it is under the countertop), and a clean-out would permit the cleaning of the pipes.

Fittings

All DWV systems require various sized fittings and pipes which are measured by their internal diameter of both the pipes and the fittings which, and in most cases are schedule 40 PVC wye's, tee's, elbows ranging from 90 degrees to 22.5 degrees for both inside diameter fitment (street) as well as outer diameter fitment (hub), repair and slip couplings, reducer couplings, and pipe which is typically ten feet in length. All DWV system fittings sizes are based on the inside diameter of the pipe that goes into the fittings. These are known as hub fittings. Sizes for hub fittings such as wye's and tee's and crosses are based on the inside diameter of the pipe that goes into the hub of the fittings. Items such as washer boxes and Studor vents are also measured by the internal diameter of the fittings.

Schedule 40 PVC DWV systems are ideal for several different reasons and are replacing cast iron DWV systems in many municipalities in the US because of issues that cast iron systems present. Parts are no longer available for cast iron plumbing repairs or for installation due to being phased out for lighter and more sanitary materials.

Since the advent of PVC and solvent weld adhesives, which is what holds the fittings together by melting the material into itself, along with the proper placement of support throughout the dwv system using strapping and jhooks as well as knowledge of boring holes in structural framing without comprising the integrity, a pvc dwv system can typically be installed by one individual experienced plumber as opposed to cast iron, which requires several people in order to install and remove.

Most pvc dwv systems that replace cast iron systems require the complete removal of the cast iron in order to provide a proper functioning dwv system leaving only enough cast iron pipe (at the lowest point to the ground in which it tyes into the sewage) in order for a specialized rubber boot coupling, known as a fernco, to be installed in order to join the pvc system to waste drainage. A special fitting known as a test tee should immediately follow the installation of the fernco in order to adequately test the system to make sure no leaks are present and that adequate vent pressure is draining the waste water correctly.

The means to properly test any dwv system is done with an inflatable apparatus known as a test ball which is placed in a test tee which should be located at the bottom most point of the system before going into the ground.

See also

References

- ↑ Gee, Steve (30 July 2007). "Cat burglar's crude escape". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- ↑ "24 CFR § 3280.611 - Vents and venting".

- ↑ "Asbestos Waste Pipes – Everything You need to Know". Asbestos-Sampling.com. Retrieved 12 December 2023.

- ↑ "24 CFR § 3280.611 - Vents and venting".

- ↑ Saltzman, Reuben (21 November 2012). "Illegal Plumbing Products in Minnesota". Star Tribune.

Mechanical vents are not allowed in Minnesota. These are often referred to as cheater vents, and they come in two varieties - an air admittance valve and a check vent.

Further reading

- Fink, Justin (16 September 2015). "Drain-Waste-Vent Systems". Fine Homebuilding. Taunton Press. 154: 18–19. Retrieved 25 September 2015.