| 339th Regiment 339th Infantry Regiment | |

|---|---|

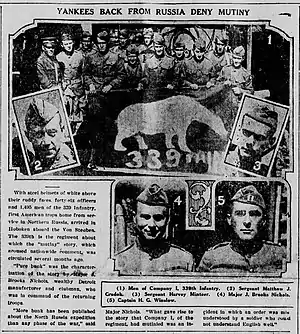

Men of the American Expeditionary Force return home from service in Northern Russia, arrived in Hoboken aboard the SS Von Steuben. (2) Sergeant Matthew J. Gradok. (3) Sergeant Harvey Minteer. (4) Major J. Brooks Nichols (5) Captain H. G. Winslow. | |

| Active | 2 August 1918 — 5 August 1919 (1 year and 3 days) |

| Country | |

| Branch | United States Army |

| Type | Infantry |

| Size | Regiment |

| Nickname(s) | Detroit's Own Polar Bears |

| Motto(s) | "We Finish With The Bayonet" |

| Engagements | Russian Civil War (Polar Bear Expedition) |

| Insignia | |

| Distinctive unit insignia |  |

The American Expeditionary Force, North Russia (AEF in North Russia) (also known as the Polar Bear Expedition) was a contingent of about 5,000 United States Army troops[1] that landed in Arkhangelsk, Russia as part of the Allied intervention in the Russian Civil War. It fought the Red Army in the surrounding region during the period of September 1918 through to July 1919.

History

Background

U.S. President Woodrow Wilson sent the Polar Bear Expedition to Russia in response to requests from the governments of Great Britain and France to join the Allied Intervention in North Russia (also known as the North Russia Campaign). The British and French had two objectives for this intervention:[2]

- Preventing Allied war material stockpiles in Arkhangelsk (originally intended for the recently collapsed Eastern Front) from falling into German or Bolshevik hands

- Mounting an offensive to rescue the Czechoslovak Legion, which was stranded along the Trans-Siberian Railroad

On July 14, 1918, the U.S. Army's 85th Division left their training camp at Camp Custer, Michigan for the Western Front in France. Three days later, President Wilson agreed to limited participation by American troops in the Allied Intervention with the stipulation that they would only be used for guarding the stockpiled war material. When U.S. Army General John J. Pershing received the directive from President Wilson, he changed the orders for the 339th Infantry Regiment, along with the First Battalion of the 310th Engineers plus a few other ancillary units from the 85th Division. Instead of heading for France, these units were trained and re-outfitted in England with Russian guns and then sent to North Russia. They arrived in Arkhangelsk on September 4, 1918, coming under British command. (Allied expeditionary forces had occupied Arkhangelsk on August 2, 1918.)

See American Expeditionary Force, Siberia for information on the 7,950 American soldiers and officers sent to Vladivostok, Russia at the same time.[3]

Expedition

When the British commanders of the Allied Intervention arrived in Arkhangelsk on August 2, 1918, they discovered that the Allied war material had already been moved up the Dvina River by the retreating Bolshevik forces. Therefore, when the American troops arrived one month later, they were immediately used in offensive operations to aid in the rescue of the Czech Legion. The British commanders sent the First Battalion of the 339th Infantry up the Dvina River and the Third Battalion of the 339th up the Vologda Railroad where they engaged and pushed back the Bolshevik forces for the next six weeks.[4]

However, these two fronts each became hundreds of miles (kilometers) long and were extremely narrow and difficult to supply, maintain, and protect. By the end of October 1918, they were no longer able to maintain the offensive and acknowledging their fragile situation and the rapid onset of winter, the Allies began to adopt a defensive posture. The Allied commanders also soon realized they would be unable to raise an effective local force of anti-Bolshevik soldiers. Thus they gave up the goal of linking up with the Czech Legion and settled in to hold their gains over the coming winter. During that winter, the Bolshevik army went on the offensive, especially along the Vaga River portion of the Dvina River Front, where they inflicted some casualties and caused the Allies to retreat a considerable distance.

During their time in North Russia, the American forces suffered more than 210 casualties, including at least 110 deaths from battle, about 30 missing in action, and 70 deaths from disease, 90% of which were caused by the Spanish flu. An October 1919 report gives the casualties as 553: 109 killed in battle; 35 died of wounds; 81 from disease; 19 from accidents/other causes; 305 wounded and 4 POWS (released).[5]

Withdrawal

Following the Allied Armistice with Germany on November 11, 1918, family members and friends of soldiers in the AEF began writing letters to newspapers and circulating petitions to their representatives in the U.S. Congress, asking for the immediate return of the force from North Russia. In turn, the newspapers editorialized for their withdrawal and their congressmen raised the issue in Washington, D.C. Meanwhile, aware of not only the change in their mission, but also of the Armistice on the Western Front and the fact that the port of Arkhangelsk was now frozen and closed to shipping, the morale of the American soldiers plummeted. They asked their officers why they were fighting Bolshevik soldiers in Russia and did not receive a clear answer, other than that they had to fight to survive and avoid the Bolshevik army pushing them into the Arctic Ocean.

Early in 1919, instances of rumored and actual mutinies in the Allied ranks became frequent. On July 15, 1919, it was reported by the Alaska Daily Empire that rumors of mutiny were "bunk" and that commander Major Nichols reported “What gave rise to the story that Company I, of the regiment, had mutinied was an Incident (sic.) to which an order was misunderstood by a soldier who could not understand English well.”[6] President Wilson directed the War Department on February 16, 1919, to begin planning the withdrawal of AEF in North Russia from Northern Russia. In March 1919, four American soldiers in Company B of the 339th Infantry drew up a petition protesting their continued presence in Russia and were threatened with court-martial proceedings.

U.S. Army Brigadier General Wilds P. Richardson arrived in Arkhangelsk aboard the icebreaker Canada on April 17, 1919, with orders from General Pershing to organize a coordinated withdrawal of American troops "...at the earliest possible moment." On May 26, 1919, the first half of 8,000 volunteer members of the British North Russian Relief Force arrived in Arkhangelsk to relieve the American troops. In early June, the bulk of the AEF in North Russia sailed for Brest, France and then for New York City and home—which for two-thirds of them was in the state of Michigan. During the withdrawal, the men of the AEF in North Russia decided to call themselves "Polar Bears" and were authorized to wear the Polar Bear insignia on their left sleeve. On July 15, 1919, it was reported by the Alaska Daily Empire that forty-six officers and 1,495 men of the Polar Bear Expedition, were the first American troops to return home from service in Northern Russia, arrived in Hoboken, New Jersey aboard the Von Steuben.[6] The AEF in North Russia officially disbanded on August 5, 1919. During their time in North Russia, the American forces suffered more than 210 casualties, including at least 110 deaths from battle, about 30 missing in action, and 70 deaths from disease, 90% of which were caused by the Spanish flu. An October 1919 report gives the casualties as 553: 109 killed in battle; 35 died of wounds; 81 from disease; 19 from accidents/other causes; 305 wounded and 4 POWS (released).[5]

Several years after the American troops were withdrawn from Russia, President Warren G. Harding called the expedition a mistake and blamed the previous administration.[7]

Aftermath

A year after all of the expedition members had returned home, in 1920 Polar Bear veterans began lobbying their state and Federal governments to obtain funds and the necessary approvals to retrieve the bodies of at least 125 of their fellow American soldiers which were then believed to have been buried in Russia and left behind. By that time, 112 sets of remains had already been transferred to the United States.[8] By 1929, additional research found that 226 fallen Polar Bears had originally been buried in North Russia,[9] with a total of approximately 130 sets of U.S. soldier remains then estimated to still be buried in North Russia. Hampered by the lack of diplomatic recognition between the United States and the Soviet Union, it took many years before they finally received permission. An expedition under the auspices of the Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW) was successful in organizing and conducting a recovery mission in the autumn of 1929 that found, identified and brought out the remains of 86 U.S. soldiers.[10] The remains of 14 AEF in North Russia soldiers were shipped by the Soviet Union to the U.S. in 1934,[11] which reduced the number of U.S soldiers still buried in North Russia to about 30.

The remains of 56 AEF soldiers were eventually re-buried in plots surrounding the Polar Bear Memorial by sculptor Leon Hermant in White Chapel Memorial Cemetery, Troy, Michigan in a ceremony on May 30, 1930.[12][13]

Harold Gunnes, who was born in 1899, died on March 11, 2003. Gunnes was believed to have been the last living American to have fought in the Allied Intervention near the port of Arkhangelsk on the White Sea.[14]

See also

- American Expeditionary Force, Siberia

- North Russia intervention

- John Cudahy (Served with 339th Infantry)

- First Red Scare

References

- ↑ Willett 2003, p. 267

- ↑ Joel R. Moore, Harry H. Mead and Lewis E. Jahns, "The History of The American Expedition Fighting the Bolsheviki" (Nashville, TN, The Battery Press, 2003), pp. 47–50

- ↑ Willett 2003, pp. 166, 170

- ↑ Nelson, James Carl. The Polar Bear Expedition: The Heroes of America’s Forgotten Invasion of Russia, 1918-1919 (2019) ch 1.

- 1 2 "Ludington Daily News Michigan". October 21, 1919. Retrieved December 4, 2014 – via Google News Archive Search.

- 1 2 Alaska Daily Empire 1919, p. 1

- ↑ American soldiers faced Red Army on Russian soil, Army Times, September 16, 2002

- ↑ "Lawrence Journal-World September 25, 1929". Retrieved December 4, 2014 – via Google News Archive Search.

- ↑ The Tuscaloosa News September 10, 1929

- ↑ "Prescott Evening Courier March 19, 1930". Retrieved December 4, 2014 – via Google News Archive Search.

- ↑ The Pittsburgh Press August 17, 1934

- ↑ "Burials at the Polar Bear Monument, White Chapel Cemetery, Troy, Michigan". May 30, 1930. Retrieved March 18, 2013.

- ↑ Sobczak, John (2009). A Motor City year. Wayne State University Press. p. 69. ISBN 9780814334102. Retrieved March 18, 2013.

- ↑ VFW Magazine 2003, p. 14

Bibliography

- Alaska Daily Empire (July 15, 1919). "Yankees back from Russia deny mutiny". Alaska Daily Empire. Juneau, Alaska. pp. 1–8. ISSN 2576-9235. OCLC 1023038927. Retrieved July 15, 2019.

- Bozich, Stanley J. and Jon R. Bozich (1985). "Detroit's Own" Polar Bears: The American North Russian Expeditionary Forces 1918–1919. Polar Bear Publishing Co. ISBN 0-9615411-0-5.

- Carey, Neil G. (1997). Fighting the Bolsheviks. Presidio. ISBN 0-89141-631-5.

- Goldhurst, Richard (1978). The Midnight War. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-023663-1.

- Gordon, Dennis (1982). Quartered In Hell: The Story of American North Russian Expeditionary Force 1918-1919. The Doughboy Historical Society and G.O.S., Inc. ISBN 0-942258-00-2.

- Guins, George Constantine (1969). The Siberian intervention, 1918–1919. Russian Review Inc.

- Halliday, E. M. (2000). When Hell Froze Over. ibooks, Inc. ISBN 0-7434-0726-1.

- Hendrick, Michael (1972). An Investigation of American Siberian intervention (1918–1920). Texas Southern University Press.

- Hudson, Miles (2004). Intervention in Russia 1918–1920 : A Cautionary Tale. Pen and Sword. ISBN 1-84415-033-X.

- Jahns, Lewis E., The History of the American Expedition Fighting the Bolsheviki Campaigning in North Russia 1918–1919. Project Gutenberg.

- Kindall, Sylvian G. (1945). American Soldiers in Siberia. Richard R. Smith.

- Moore, Joel; et al. (2003). The American Expedition Fighting the Bolsheviki: Campaigning in North Russian, 1918–1919. The Battery Press. ISBN 0-89839-323-X.

- Nelson, James Carl. The Polar Bear Expedition: The Heroes of America’s Forgotten Invasion of Russia, 1918-1919 (2019) excerpt

- Wards, John With the "Die-Hards" in Siberia (1920; Reprint 2004 Reprint ISBN 1-4191-9446-1 Project Gutenberg.

- White, John Albert (1950). The Siberian Intervention. Princeton University Press.

- Willett, Robert L. (2003). Russian Sideshow: America's Undeclared War, 1918-1920. Potomac Books, Inc. ISBN 9781574884296. - Total pages: 352

- VFW Magazine (November 1, 2003). "WWI vets: last living links to a bygone era: with less than 400 of them left, these century-old warriors still have stories to tell, about the Great War". VFW Magazine. Veterans of Foreign Wars of the United States. 91 (3). ISSN 0161-8598.

External links

- "M" Company 339th Infantry in North Russia published 1920

- Voices of a Never Ending Dawn Producer/Director Pamela Peak's web site for her film about the Polar Bear Expedition. The film's broadcast premiere was on November 8, 2009 on WTVS-Detroit Public TV. It will be shown on PBS member stations across the United States in the coming months.

- Polar Bear Expedition Digital Collections An interactive site featuring the digitized Polar Bear collections of various soldiers and organizations housed at the Bentley Historical Library. The open materials consist of 110 individual collections of primary source material, including diaries, maps, correspondence, photographs, ephemera, printed materials, and a motion picture.

- "Detroit's Own" Polar Bear Memorial Association

- America's Secret War Hundreds of photos.

- "The Strange, Sad Death of Sergeant Kenney" Archived September 29, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- North Russian Expeditionary Force 1919, The Journal and Photographs of Yeoman of Signals George Smith, Royal Navy

- A Polar Bear In North Russia The great-granddaughter of a Polar Bear blogs about his experiences in North Russia, sharing photos and memorabilia from his scrapbook.

- US State Department papers relating to North Russia 1918

- White Chapel Cemetery at Find A Grave

- The History of the American Expedition Fighting the Bolsheviki Campaigning in North Russia 1918–1919

- Personal account of Private First Class Robert A. Burns, Robert A. Burns Collection (AFC/2001/001/64342), Veterans History Project, American Folklife Center, Library of Congress.