| Part of a series on the |

| History of Jews and Judaism in Poland |

|---|

| Historical Timeline • List of Jews |

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Peshischa Hasidism |

|---|

| Rebbes & Disciples |

Hasidic Judaism in Poland is the history of Hasidic Judaism and Hasidic philosophy in Poland. Hasidic Judaism in Poland began with Elimelech Weisblum of Lizhensk (Leżajsk) (1717-1787) and to a lesser extent Shmelke Horowitz of Nikolsburg (Mikulov) (1726-1778). Both men were leading disciples of Dov Ber of Mezeritch (Medzhybizh) (c. 1704–1772), who in part was the successor to the Baal Shem Tov (c. 1698–1760) who founded Hasidic Judaism in Western Ukraine. Today, a sizable portion of contemporary Hasidic Judaism and Hasidic dynasties trace their genealogical and ideological origin to Polish Hasidism.

Noam Elimelech

While Reb Shmelke of Nikolsburg was an influential figure from which the Nikolsburg Hasidic dynasty descends. It was Reb Elimelech of Lizhensk from which Polish Hasidism finds it truest origins. In his seminal work, "Noam Elimelech", Reb Elimelech of Lizhensk laid down the ideological foundation for Polish Hasidism, chiefly the doctrine of popular tzaddikism, which would later become the centre of much controversy. Reb Elimelech believed that the role of the rebbe was that of a miracle worker, and the rebbe was to serve as the imputes of God by embodying and channeling the Ayin-Yesh, through a process of mystical leadership based in Kabbalah and the philosophy of the Baal Shem Tov. Reb Elimelech believed that the primary awakening that pushes a person to repent comes through the rebbe, and that the spirit of Shabbos is the greatest catalyst for this repentance. He believed that the rebbe should commit himself to praying for the material and spiritual welfare of his followers, and that the rebbe's disciples need to bind themselves to the rebbe's powers by means of redemptive gifts, through which the rebbe was to be supported. Reb Elimelech also clearly believed that the rebbe was to not live a lavish lifestyle and that he must always stay humble in such a position of power. Reb Elimelech had four main students each of whom founded their own Hasidic courts and developed their own Hasidic philosophies based in the teaching of Reb Elimelech. Those four disciples were Yaakov Yitzchak Horowitz, "the Seer of Lublin" (1745-1815), Yisroel Hopstein, "the Maggid of Kozhnitz" (1737–1814), Avraham Yehoshua Heshel, "the Apter rebbe" (1748-1825) and Menachem Mendel Torem of Rimanov (1745-1815). The Seer of Lublin became the leading figure of Polish Hasidism, while Menachem Mendel of Rimanov became the leading figure of Galacian Hasidism, thus separating the movement into two different ideological sects based on geography.[1]

Early Polish Hasidism

The court of Lublin

The Seer of Lublin is widely considered to be the most influential Hasidic leader in Poland at the beginning of the nineteenth century. Though he did not found a dynasty, the majority of the Hasidic figures living at his time in that region considered themselves to be his disciples. In 1785, only two years before the death of Reb Elimelech of Lizhensk, the Seer of Lublin established his own Hasidic court in the town of Lantset, later moving it to Chekhov and finally Lublin itself. The Seer greatly expounded on Reb Elimelech's concept of the rebbe. He believed that the rebbe should be a charismatic leader, who has the divine authority to lead a community. In the Seer's precept, the rebbe served as an intermediary between his community and God, and because of that, the rebbe shouldn't be questioned. The Seer believed that the burden of piety was much too great for most individuals, and so one should fully place his emotional, spiritual and even physical wellbeing in the hands of his rebbe. In return for this, the rebbe's followers were expected to support the rebbe financially and be loyal to him. Because of this belief, the Seer became considerably wealthy and used his new found wealth to gain more followers. In essence, the Seer's principle tenant was that the rebbe must be all-encompassing figure who plays an entirely autocratic role in the lives of his followers. Many of the Seer's disciples fully embraced this belief, which became the foundation of the Lublin philosophical school, which has deep ideological underpinnings in many contemporary Hasidic dynasties. Among the Seer's followers who embraced this belief were Moshe Teitelbaum, the "Yismach Moshe" (1758-1841) from which Siget and Satmar Hasidism derive, Sholom Rokeach, the "Sar Sholom" (1781-1855), from which Belz Hasidism derives, Tzvi Elimelech Spira (1783-1841), from which Dinov and Munkacs Hasidism derive. That being said, some of the Seer's younger and more intellectual disciples completely rejected his beliefs surrounding the role of the rebbe. The leader of this coalition was Yaakov Yitzchak Rabinowicz, the "Yid Hakudosh" (1766-1813) who founded the Peshischa school of Hasidic thought based in the town of Przysucha.[2][3]

Peshischa Hasidism

The Yid HaKudosh

The Yid Hakudosh found the atmosphere of the Seer's court to be entirely suffocating. Nearing the end of the 18th-century, the Yid Hakudosh left Lublin alongside a delegation of the Seer's most prodigious pupils and founded his own Hasidic school of thought in Przysucha (Peshischa). The Yid Hakudosh believed that an individual should always examine his intentions, and if they are corrupt he should cleanse them through a process of self-understanding. It was this fundamental belief in individuality and autonomy of self which resulted in a continuous dispute between the Seer and the Yid Hakudosh. While the Seer believed that it was his duty to bring an end to the Napoleonic wars, by using Kabbalah and prayer, the Yid Hakudosh refused to join this spiritual endeavour, as he believed that one finds redemption through a highly personal process of self-cleansing rather than through a rebbe. The Yid Hakudosh believed that humility is the core virtue of a person who truly knows himself, recognizing his own imperfection. He believed that one should not be influenced by the status quo as it can lead to impure motives. It was clear to him that path to enlightenment required critical judgment of religious routine, once famously stating that "all the rules that a person makes for himself to worship God are not rules, and this rule is not a rule either". Ultimately, the Yid Hakudosh founded Peshischa as elitist approach to Hasidism, in which he parred traditional Talmudic learning with the highly spiritual Kavanah of Hasidism. After his death he was succeeded by his main disciple Simcha Bunim Bonhardt, the "Rebbe Reb Bunim" (1765-1827) who would soon become the most controversial figures in the history of Polish Hasidism. The Yid Hakudosh's is the patriarch of the Biala and Porisov Hasidic dynasties.[4]

The Rebbe Reb Bunim

The Rebbe Reb Bunim was an atypical Hasidic leader. He was of German origin and received a secular scientific education in Leipzig. After succeeding the Yid HaKudosh, the Rebbe Reb Bunim brought Peshischa to its highest point and kickstarted a counter-revolutionary movement which challenged the Hasidic norm. While under the Yid HaKudosh, Peshischa was closer to a philosophy whereas, under the Rebbe Reb Bunim it was transformed into a religious movement. Under the Rebbe Reb Bunim's leadership, centers were created across Poland that held ideologically alliance to Peshischa. These centers preached his ideals of rationalism, radical personhood, independence and the constant quest for authenticity, which challenged contemporary Hasidic leadership. The Rebbe Reb Bunim was adamantly against the autocratic and dynastic nature which had defined Hasidic leadership of his time. He encouraged his students, to think critically and to be independent of him. He believed the role of the rabbi was that of a teacher who helped his disciples develop their own sense of autonomy and not of an enforcer or impetus of God. Those students who are unable to accept responsibility for themselves were considered unfit to be part of Peshischa. The Rebbe Reb Bunim saw that the ultimate purpose of the Torah and the mitzvoth is to draw a person close to God, though an approach that can only be achieved with humility and joy, and that a critical and intellectual interpretation of the Torah is crucial for enlightenment. He thus concluded that the service of God demanded both passion and analytical study. During his time, there was little to no study of Kabbalah and the emphasis was not on trying to understand God, but on trying to understand the human being. He also encouraged his students to study the secular sciences and the writings of the Rambam. The Rebbe Reb Bunim ultimately believed that Religion was not simply an act of adopting a system of beliefs, but that test and trial were needed, and one had to ascertain through introspection whether one's beliefs were genuine or not. These sentiment spread throughout Poland, leading to several attempts by Hasidic leadership of his time to excommunicate the Rebbe Reb Bunim.[5]

In 1822, at the wedding of Avraham Yehoshua Heshel's grandson in Ustyluh, Ukraine, an attempt was made by the majority of the Hasidic leaders of Poland and Galicia to excommunicate the Rebbe Reb Bunim. Several dignitaries such as Tzvi Hirsh Eichenstein of Zidichov (1763-1831) and Naftali Zvi Horowitz of Ropshitz (1760-1827) came to the wedding to publicly speak out against the Rebbe Reb Bunim, in hopes that Avraham Heshel along with other leading rabbis, would agree to excommunicate him and the Peshischa movement. Knowing that he would be slandered, the Rebbe Reb Bunim sent his top students to go to the wedding and defend the Peshischa method. During the course of the festivities, a public debate was held in which combatants of Peshischa appealed to Avraham Heshel to decide whether to ban Peshischa or not. They described Peshischa as a movement of radical intellectual pietists and non-conformists who endangered the Hasidic establishment. They also criticized the Rebbe Reb Bunim for dressing in contemporary German fashion as opposed to the traditional Hasidic garb, claiming that his German pedigree debarred him from being an adequate Hassidic leader. Nearing the end of the debate, Avraham Heshel turned towards Yerachmiel Rabinowicz (1784-1836), the son of the Yid Hakudosh, and asked him what he thought of the Rebbe Reb Bunim. Yerachmiel responded in approbation towards the Rebbe Reb Bunim, and thus Avraham Heshel ended the debate. Following the intense debates at the wedding, hundreds of young Hasids flocked to Peshischa.[6]

After the rebbe Reb Bunim's death in 1827, Peshischa split into two factions. The more radical of which was led by Menachem Mendel Morgensztern, the "Kotzker Rebbe" (1787-1859) who founded Kotzk Hasidism, while the less radical was led by the Rebbe Reb Bunim's son, Avraham Moshe Bonhardt, the "Ilui Hakudosh" (1800-1827) who reluctantly led the opposing delegation. After the Ilui Hakudosh's death a year after, his followers accepted Israel Yitzhak Kalish of Vurke (1779-1848) from whom Vurka and Amshinov Hasidism derive. Among the Rebbe Reb Bunim other follower's were Yitzchak Meir Rotenberg-Alter, the "Chiddushei HaRim" (1799-1866) from whom Ger Hasidism derives, Mordechai Yosef Leiner, "the Ishbitzer Rebbe" (1801-1854) from whom Izhbitza-Radzin Hasidism derives, Shraga Fayvel Dancyger (1791-1848) from whom Aleksander Hasidism derives and Shmuel Abba Zychlinski (1809-1879), from whom Zychlin Hasidism derives.[7]

Late 19th to 20th-century

The end of the 19th-century saw the innovation of Hasidic yeshivas. Until this point, yeshivas had been identified with the Misnagdim or the Musar movement in Lithuania, and the widespread adoption of the Yeshiva system in Polish and Galician Hasidism, represented a rising trend of conservative values tied to traditional Torah study. The first Hasidic yeshivas were founded in the late 19th-century in Wiśnicz by Shlomo Halberstam (1847–1905), a grandson of the Chaim Halberstam, "the Divrei Chaim " (1793-1876) who established the Bobov Hasidic dynasty as an offshoot of his grandfather's dynasty of Sanz. Following this a Yeshiva was established in Sochaczew by Avrohom Bornsztain (1838-1910), the son-in-law of the Kotzker Rebbe and founder of the Sochatchov Hasidic dynasty. During the early 20th-century almost every Hasidic dynasty no matter its size, has its own yeshiva. At this time, the three major Polish dynasties by size were Ger, Sochatchov, and Aleksander all of whom based their teachings in Peshischa Hasidism. The fourth Ger Rebbe, Avraham Mordechai Alter was amongst the founders of Agudas Yisroel in 1912. Following the rise of Zionism and secularism in Polish Jewry, a growing movement of Orthodox fanaticism become prevalent in Hasidic circles, especially those of Belz, Sanz and Satmar as well their respective offshoots who opposed not only Zionism but even the Agudas Yisroel. The Holocaust dealt a mortal blow to Hasidism in Poland, and those survivors adopted an even stricter view of Halacha and Hasidic customs. Several Holocaust survivors began to doubt the wisdom of Hasidic leaders who had despised Zionism before the Holocaust, some of whom had urged their followers to remain in the Diaspora but had unhesitatingly taken the opportunity to escape to safety in their own time of need.[8]

Post-Holocaust

After the Holocaust several Hasidic rebbe's rebuilt their communities in North America and Israel, particularly in Williamsburg, Monsey, and Borough Park. Despite no longer living in Eastern Europe, almost every Hasidic group has preserved their East European features, whether it be the names of the various Hasidic courts, their customs of everyday clothing, culinary traditions, and religious lifestyle, but particularly with the survival of Yiddish as the main spoken language among most Hasidic communities.[8]

Gallery

Błażowa, 1930s

Błażowa, 1930s Sanok, 1930s

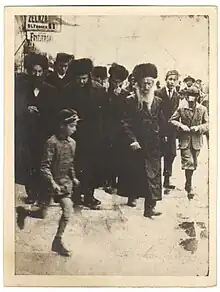

Sanok, 1930s Sanok

Sanok Przeworsk (Pshevorsk)

Przeworsk (Pshevorsk) "Hasidic boys in Poland"

"Hasidic boys in Poland" Rabbi Mordechai Yosef Elazar Leiner of Radzin on left, 1928

Rabbi Mordechai Yosef Elazar Leiner of Radzin on left, 1928 Rabbi Shmuel Shlomo Leiner of Radzin

Rabbi Shmuel Shlomo Leiner of Radzin Chachmei Lublin Yeshiva, 1932

Chachmei Lublin Yeshiva, 1932

See also

References

- ↑ "Elimelech Of Lizhensk | Jewish teacher and author". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-11-25.

- ↑ "YIVO | Ya'akov Yitsḥak Horowitz". yivoencyclopedia.org. Retrieved 2020-11-25.

- ↑ "Jacob Isaac Ha-Ḥozeh mi-Lublin". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2020-11-25.

- ↑ "YIVO | Pshiskhe Hasidic Dynasty". yivoencyclopedia.org. Retrieved 2020-11-26.

- ↑ Rosen, Michael (2008). The Quest for Authenticity: The Thought of Reb Simhah Bunim. Urim Publications. p. 55. ISBN 978-965-524-003-0.

- ↑ Rosen, Michael (2008). The Quest for Authenticity: The Thought of Reb Simhah Bunim. Urim Publications. pp. 14, 23. ISBN 978-965-524-003-0.

- ↑ Rosen, Michael (2008). The Quest for Authenticity: The Thought of Reb Simhah Bunim. Urim Publications. pp. 26, 56. ISBN 978-965-524-003-0.

- 1 2 "YIVO | Hasidism: Historical Overview". yivoencyclopedia.org. Retrieved 2020-11-26.