| Royal Prussia | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Royal dependency of Poland | |||||||||

| 1466–1569 | |||||||||

_Lob.svg.png.webp) Flag

| |||||||||

Map of Royal Prussia (light pink) | |||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

| • Coordinates | 54°N 19°E / 54°N 19°E | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

| 19 October 1466 | |||||||||

| 1 July 1569 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | Poland Russia | ||||||||

Royal Prussia (Polish: Prusy Królewskie; German: Königlich-Preußen or Preußen Königlichen Anteils, Kashubian: Królewsczé Prësë) or Polish Prussia[1] (Polish: Prusy Polskie;[2] German: Polnisch-Preußen)[3] was a province of the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland, which was established after the Second Peace of Toruń (Thorn) (1466) from territory in Pomerelia and western Prussia which had previously been part of the State of the Teutonic Order (these areas were officially occupied by the Teutonic Knights in 1308, previously they also belonged to Poland).[4][5][6] Royal Prussia retained its autonomy, governing itself and maintaining its own laws, customs, rights and German language for German minority.[7][8]

In 1569, Royal Prussia was fully integrated into the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland and its autonomy was largely abandoned.[9] As a result, the Royal Prussian parliament was incorporated into the Sejm of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.[10] In 1772 and 1793, after first and second partition of Poland, the former territory of Royal Prussia was annexed by the Kingdom of Prussia and subsequently re-organized into the province of West Prussia. This occurred at the time of the First Partition of Poland, with other parts of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth being annexed by the Russian Empire and Habsburg Austria.

Geography

The area consisted of the following territories:

- Pomerelia

- Gdańsk Pomerania (Pomeranian Voivodeship (1466–1772)) with the mouth of the Vistula, including the city of Gdańsk

- the Lauenburg and Bütow land, at times ruled as enfeoffed to Poland by the Duchy of Pomerania (Farther) later succeeded by Brandenburg-Prussia

- Chełmno Land and Michałów Land (Chełmno Voivodeship), including the city of Toruń

- Gdańsk Pomerania (Pomeranian Voivodeship (1466–1772)) with the mouth of the Vistula, including the city of Gdańsk

- Western part of the original Prussia, which was forcibly ceded from the Teutonic Order in the Second Peace of Thorn (1466) to the Kingdom of Poland

- the Prince-Bishopric of Warmia (Ermland) with Frauenburg (Frombork), Heilsberg (Lidzbark Warmiński) and Allenstein (Olsztyn)[11]

- the Malbork Land, territory covering northern parts of Pomesania and Pogesania with Marienburg (Malbork), Stuhm (Sztum), Christburg (Kiszpork, later Dzierzgoń) and Tolkemit (Tolkmicko), including the City of Elbing (Elbląg)

In contrast, southern remainder of Pomesania and Pogesania, including Marienwerder (Kwidzyn), Deutsch Eylau (Iława), Riesenburg (Prabuty), Rosenberg (Susz), Bischofswerder (Biskupiec), Saalfeld (Zełwałd, later Zalewo), Freystadt (Kisielice), Mohrungen (Morąg), Preußisch Holland (Pasłęk) and Liebstadt (Libsztat, later Miłakowo), formed Upper Prussia (German: Oberland, Polish: Prusy Górne) constituting the westernmost part of the Prussian territory left to the Teutonic Knights, known as Teutonic or Monastic Prussia with Königsberg as its capital, later secularized in 1525 to become Ducal Prussia ruled by the Protestant dukes of the Hohenzollern dynasty. From 1618 this area was ruled in personal union with the Electorate of Brandenburg as Brandenburg-Prussia. In 1657 the Treaty of Wehlau granted full independence to the Duchy of Prussia, allowing its later elevation to Kingdom in Prussia.

History

Prussian Confederation

Originally Polish, the Pomerelian part of the region was gradually emancipating during the fragmentation of Poland upon the death of Bolesław III Wrymouth in 1138, culminating in an almost independent Duchy of Pomerelia in 1227. It was, however, reclaimed by the Polish state by 1282, but retained some grade of autonomy.[12] During the rule of Władysław I the Elbow-high of Poland, the Margraviate of Brandenburg challenged his rule over the territory in 1308, leading Władysław to request assistance from the Teutonic Knights, who had ousted the Brandenburgers, but subsequently seized Pomerelia for themselves and incorporated it into the Teutonic Order state in 1309 (Teutonic takeover of Danzig (Gdańsk) and Treaty of Soldin (Myślibórz)). At the beginning of the 15th century, the lands held by the Teutonic Knights were inhabited as a whole by a mixed population; it is estimated that there were about 200 000 Germans in the state altogether, followed by 140 000 native Prussians located in the Prussia proper (east of Vistula), as well about 140 000 Poles in Pomerelia and Masuria.[13]

The burden of taxation and the arbitrary way of governing caused resistance among the people of Prussia. The burghers of the great Prussian cities began to organize themselves. The first organized body was the Lizard League founded by the Chelmno Land nobility in 1397.[14] After being checked at the Battle of Grunwald, the Teutonic Knights's prestige declined, most towns and castles, as well as three Prussian bishops, swore loyalty to the Polish king.[15] Although the Order soon regained control over most of the territory, by the 1411 Peace of Thorn they were forced to pay large compensation of 100,000 kop groszy for the return of prisoners,[16] which became a financial burden on the citizenry. Facing the opposition the komtur of Danzig ordered to execute the city's mayor Konrad Letzkau along with two councillors and five Chełmno nobles without a trial.[17]

In order to protect their rights nobles and burghers created for the first time a joint assembly in 1412.[18] Subsequent peace treaties (1422 and 1435) with Poland gave the Order's subjects the right to throw off its sovereignty if it violated them.[17] In 1440, as the tax burden rose, indigenous nobles and Hanseatic cities established the Prussian Confederation at Marienwerder (Kwidzyn) in resistance of the Order's domestic and financial policies. Confederation formed a self-governing bicameral institution, representing nobles and burghers of the province, which took decisions unanimously.[19]

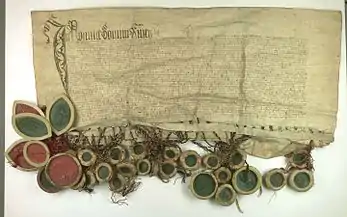

The Confederation was led by the citizens of Danzig, Elbing, and Thorn. The gentry from Chełmno Land and Pomerelia participated as well. After the monastic knights complained to the Emperor and Council of Basel, the Prussian parliament had to dissolve itself in 1449, but immediately resumed its clandestine activities. In turn, in February 1454, the Confederation sent a delegation, under Hans von Baysen, to King Casimir IV Jagiellon of Poland, to ask him for support against the Teutonic Order's rule and for incorporation of their homeland into the Kingdom of Poland. In this treaty, Prussian delegates declared the Polish king the only true sovereign of their lands, justified by the historical fact that the king of Poland had earlier ruled them. After lengthy negotiation, on 6 March 1454, the Royal Chancellery issued the Incorporation Act by which king Kazimierz Jagiellończyk accepted inhabitants of the Prussian lands Prussians as subjects, incorporated Prussia to the Polish kingdom and granted them a large autonomy.[20] The Prussian estates received confirmation of their rights and privileges, were exempted from paying the Pfundzoll, received the ius indigenatus, the right to decide on Prussian affairs at their own estate assemblies and a guarantee of the freedom of trade.[21] Thorn, Elbing, Königsberg and Danzig (Danzig law) were to retain the right to mint coins during the war, although with the image of the Polish king.[22]

Thirteen Years' War

After the Prussian Confederation pledged allegiance to Casimir on 6 March 1454, the Thirteen Years' War ("War of the Cities") began. King Casimir IV Jagiellon appointed Baysen as the first war-time governor of Royal Prussia. On 28 May 1454, the king took an oath of allegiance from the citizens of Toruń (Thorn), and in June a similar oath from the citizens of Elbląg (Elbing) and Königsberg was taken.[23]

The rebellion also included major cities from the eastern part of the Order's lands, such as Kneiphof, later a part of Königsberg. Though the Knights were victorious at the Battle of Chojnice in 1454, they were not able to finance more knights in order to reconquer the castles occupied by the insurgents. Thirteen years of attrition warfare ended in October 1466 with the Second Peace of Thorn (1466), which provided for the Order's cession to the Polish Crown of its rights over the western half of Prussia, including Pomerelia and the districts of Elbing, Malbork (Marienburg), and Chełmno.

Incorporation into the Polish Crown

According to the 1454 treaty signed by King Casimir IV, Royal Prussia was incorporated into the Polish Crown and their elites enjoyed the same rights and privileges as the elites of the Polish kingdom.[24] At the same time Royal Prussia was granted a considerable degree of autonomy. Already instituted law codes were retained, only Prussians could be appointed on public offices (ius indigenatus), borders of the province had to remain intact and all decisions regarding Prussia had to be consulted with the Prussian council.[22] Thorn and Danzig retained the right to mint coins.[21]

The Polish model of political and administrative organisation was introduced into the province. Royal Prussia was divided in 1454 into four voivodeships: Pomeranian, Chełmno, Elbląg (since 1467 Malbork) and Królewiec (Königsberg), which ceased to exist after the Second Peace of Thorn. Voivodeships were divided subsequently into powiats.[21]

By the decision of the Polish Sejm in 1467[25] the main governing body of Royal Prussia was the Prussian council (German: Landesrat), which emerged from the secret council of the Prussian Confederation. Three voivodes, three castellans (of Kulm, Elbing and Danzig), three chamberlains (Polish: podkomorzy) and two delegates from each of the main cities: Thorn, Danzig and Elbing were part of the council.[25] Later bishops of Warmia (1479) and Chełmno (1482) were admitted into a council, which ultimately consisted of 17 members.[26] Since the council wasn't able to impose taxes without the consent of the commons, the gathering of all estates shortly emerged, at first known as Ständetage and later as Landtag. In years 1512-1526 it developed into a bicameral Prussian parliament.[27]

At first, the bishop of Warmia claimed that his principality was independent and subordinate only to the Pope. After a short war — the so-called "priests' war" — the matter was settled in the king's favour; in 1479 Warmia was formally incorporated into Poland. The bishop's subjects were given the right to appeal to the king, to whom they swore allegiance. The Bishop of Warmia became, ex officio, a member of the Prussian council. From 1508 the bishop headed the council.[28] The bishopric of Warmia was a suffragan of the archbishopric of Riga until 1566; after that date it was subordinated directly to the Pope. It was never part of archdiocese of Gniezno.[21]

The Prussian states stood for deep particularism. They were reluctant to participate in the institutions of the kingdom. The members of the council refused to participate in the meetings of the royal council and sent only token delegations to the royal elections in 1492, 1501 and 1506.[29] During the war the king exercised his authority over the province through the position of governor, which was first held by Hans von Baysen, and after his death in 1459 by his brother Stibor. As the governor was elected by the estates and only approved by the king, Casimir abolished this office and appointed Stibor as voivode of Malbork. In 1472, the king introduced in Prussia the office of starosta general, who was solely dependent on the king. Son of Stibor Nicholaus was appointed voivode of Malbork and administrator of Prussia. In 1485 Nicholaus resigned his office and led the Prussian opposition against the violation of Prussian privileges, above all the ius indigenatus.[30] In response, King Casimir strengthened the position of the Malbork starosta, to whom he always appointed a non-Prussian. In 1485 it was a magnate from Lesser Poland, Zbigniew Tęczyński.[31]

The situation changed in 1498 when Frederick of Saxony was elected Grand Master of the Teutonic Order and started a hostile politics against Poland in an attempt to reclaim lost territories in Royal Prussia. As a result, the newly elected bishop of Warmia, Lucas Watzenrode, and Nicholaus von Baysen began to take part in meetings of the royal council. During 1509 Sejm Watzenrode took part in a Senate meeting as the first representative of the Prussian council. Ambroży Pampowski, starosta of Malbork between 1504 and 1510, also bore the title Haupt des Landes, and although he was non-Prussian, he was accepted as such by the Prussian council.[32] A monument of the reapprochement between Prussia and the rest of the kingdom was the Statute of Prussia, promulgated in 1506, in which many Polish legal solutions were introduced into the Prussian legal system.[33] An important achievement was the establishment of a central Prussian treasury.[34] In 1511, a supreme tribunal was established for the Prussian courts, excluding the courts of Danzig, which denied the right of appeal to the Prussian court and decided cases internally. It sometimes resorted to royal and parliamentary courts.[34] Closer ties with the rest of the kingdom found support primarily among the ordinary nobility, for whom the Polish political and legal solutions were more favourable. In particular, the inheritance rules applied under Kulm law, which guaranteed inheritance also in the female line, resulted in the fragmentation of estates.

In years 1519-1521 Albrecht von Hohenzollern lost the Order's last war against Poland. As a result Order's state was secularised and became a fief of the Polish crown, held by Albrecht and his direct heirs as "dukes in Prussia".[35] Albrecht ruled as a Lutheran ruler. Lutheranism also spread in Royal Prussia, especially in the big cities. Despite the king's attempts to stop Protestantism, it was declared the ruling religion in Danzig, Elbing and Thorn (Gdańsk, Elbląg, Toruń) after 1526 (of course, part of the population remained Catholic in these cities). During the war, the Polish General Assembly descended to Toruń in 1519 and to Bydgoszcz in 1520. Some Prussian nobles attended it.[36] In 1522 the Prussian nobility gathered in the Landtag demanded the introduction of the Polish model of inheritance and land ownership, excluding the burghers. They also demanded the right to send one deputy from each province to the Polish Sejm. In 1526 the Prussian Landtag, headed by the king, established sejmiks, local assemblies of noblemen, who elected deputies to the Prussian parliament, where they sat together with representatives of 27 smaller towns. The Prussian council formed the upper house – the senate – of this assembly.[37] In 1529 a monetary union was established between Royal Prussia and Ducal Prussia and the rest of the kingdom.[38] From 1537 summons to the Sejm were continuously sent to the Prussian sejmiks. The Prussian nobility appeared permanently at the Sejm as observers. In 1548, after the death of King Sigismund the Old, for the first time, a delegation of both Prussian chambers went to the Sejm as deputies and senators.[39]

Integration into the Kingdom of Poland

In 1569, as a result of the Union of Lublin, which created the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, Royal Prussia was integrated fully into the Kingdom of Poland, and its parliament reduced to the status of a provincial assembly, also other separate Prussian institutions were dissolved.[9] The former territory was subsequently governed as Pomeranian Voivodeship, Culm Voivodeship, Malbork Voivodeship, and Prince-Bishopric of Warmia.

| History of Brandenburg and Prussia |

|---|

|

|

| Present |

|

Partitions

At the same time as the 1772 and 1793 (first and second partition of Poland), the former lands of Royal Prussia were annexed by the Kingdom of Prussia, the successor state of the Teutonic Order. In 1793, the new Kingdom of Prussia participated in the Second Partition of Poland by temporarily annexing the neighboring regions, which were almost immediately returned to the Tsarist kingdom of Poland and incorporated into the Russian Empire.

Governors

- 1454–1459: Johannes von Baysen, war-time governor

- 1459–1480: Stibor von Baysen[40]

- 1480: Niklas von Baysen, who was only elected; he refused to swear allegiance to the king. He was also Voivode of Malbork.

In 1510, after several attempts to install another governor, the office was abolished.

See also

References

- ↑ Anton Friedrich Büsching, Patrick Murdoch. A New System of Geography, London 1762, p. 588

- ↑ Zygmunt Gloger (1900). "Volume 325". In Harvard Slavic humanities preservation microfilm project (ed.). Geografia historyczna ziem dawnej polski (Historical Geography of the former Polish lands) (in Polish). Wydawnictwo Polska. pp. 82, 144.

- ↑ (in German) Polnisch-Preußen ("State Constitution of Polish-Prussia") (see: Excerpt in the publication of 1764, p. 581)

- ↑ Friedrich 2000, p. 1-2, 22-23.

- ↑ Knoll 2008, p. 42–43.

- ↑ Dwyer 2000, p. 28.

- ↑ Friedrich 2000, p. 179.

- ↑ Dr Jaroslav Miller. Urban Societies in East-Central Europe, 1500–1700. Ashgate Publishing. p. 179.

- 1 2 Daniel Stone (2001). The Polish-Lithuanian State, 1386-1795. University of Washington Press. p. 64. ISBN 0-295-98093-1.

- ↑ Friedrich 2000, p. 30-31.

- ↑ Stone, Daniel. A History of East Central Europe. University of Washington Press, 2001, ISBN 0-295-98093-1. p. 30

- ↑ Frost, Robert, The Oxford History of Poland-Lithuania, Vol. I

- ↑ Frost 2015, p. 221.

- ↑ Friedrich 2000, p. 20.

- ↑ Frost 2015, p. 108.

- ↑ Frost 2015, p. 108 & 211.

- 1 2 Frost 2015, p. 211.

- ↑ Friedrich 2000, p. 21.

- ↑ Friedrich 2000, p. 22.

- ↑ Friedrich 2000, p. 22-23.

- 1 2 3 4 Friedrich 2000, p. 23.

- 1 2 Frost 2015, p. 219.

- ↑ F. Kiryk, B. Ryś (red.) Wielka Historia Polski, t. II 1320-1506, Kraków 1997, p. 160-161

- ↑ Frost 2015, p. 218-219.

- 1 2 Friedrich 2000, p. 24.

- ↑ Frost 2015, p. 381-382.

- ↑ Frost 2015, p. 382 and 397.

- ↑ Frost 2015, p. 384-385.

- ↑ Frost 2015, p. 382.

- ↑ Frost 2015, p. 383.

- ↑ Frost 2015, p. 384.

- ↑ Frost 2015, p. 387-389.

- ↑ Frost 2015, p. 389.

- 1 2 Frost 2015, p. 389-390.

- ↑ Frost 2015, p. 393.

- ↑ Frost 2015, p. 396.

- ↑ Frost 2015, p. 398.

- ↑ Frost 2015, p. 398-399.

- ↑ Frost 2015, p. 399.

- ↑ Acten der Ständetage Preussens unter der Herrschaft des Deutschen Ordens: 5 vols., Max Toeppen (ed.), Leipzig: Duncker & Humblot, 1874–1886; reprint Aalen: Scientia, 1968–1974, vol. 5: 'Die Jahre 1458–1525', 1974. p. 90. ISBN 3-511-02940-6.

Further reading

- Dwyer, Philip G., ed. (2000). The Rise of Prussia 1700-1830. Routledge. p. 28. ISBN 978-1138837645.

- Friedrich, Karin (2000). The Other Prussia: Royal Prussia, Poland and Liberty, 1569–1772. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-58335-7.

- Frost, Robert (2015). The Making of the Polish-Lithuanian Union 1385-1569. Oxford History of Early Modern Europe. Vol. I. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191017872.

- Knoll, Paul W. (2008). "The Most Unique Crusader State. The Teutonic Order in the Development of the Political Culture of Northeastern Europe during the Middle Ages". In Ingrao, Charles W.; Szabo, Franz A. J. (eds.). The Germans and the East. Purdue University Press. ISBN 978-1557534439.

- Gerard Labuda (ed.), Historia Pomorza, vol. I–IV, Poznań 1969–2003 (also covers East Prussia) (in Polish)

- Wacław Odyniec, Dzieje Prus Królewskich (1454–1772). Zarys monograficzny, Warszawa 1972 (in Polish)

- Dzieje Pomorza Nadwiślańskiego od VII wieku do 1945 roku, Gdańsk 1978 (in Polish)