Port Neches, Texas | |

|---|---|

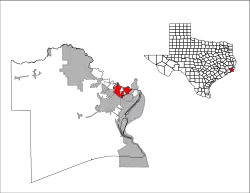

Location of Port Neches, Texas | |

| Coordinates: 29°58′51″N 93°57′37″W / 29.98083°N 93.96028°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Texas |

| County | Jefferson |

| Area | |

| • Total | 9.12 sq mi (23.62 km2) |

| • Land | 8.65 sq mi (22.41 km2) |

| • Water | 0.47 sq mi (1.21 km2) |

| Elevation | 16 ft (5 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 13,692 |

| • Density | 1,462.50/sq mi (564.68/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (Central (CST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| ZIP code | 77651 |

| Area code | 409 |

| FIPS code | 48-58940[3] |

| GNIS feature ID | 1375534[2] |

| Website | ci |

Port Neches is a city in Jefferson County, Texas, United States. The population was 13,692 at the 2020 census,[4] an increase over the figure of 13,040 tabulated in 2010. It is part of the Beaumont–Port Arthur metropolitan area.

History

The area known as Port Neches was once inhabited by tribes of the coastal-dwelling Karankawa and Atakapa Native Americans. Smith's Bluff (the future site of Sun Oil and Union Oil of California riverside property) and Grigsby's Bluff (now Port Neches) were the only two high land bluffs on the Neches River south of Beaumont, whose name is believed to have been derived from the Caddo word "Nachawi", meaning "wood of the bow", after Spanish settlers called it Río Neches.[5] Before 1780, Grigsby's Bluff, specifically that part of Port Neches immediately east of Port Neches Park, had been a Native American town for at least 1,500 years, at first of the Karankawa tribe, whose 7-foot (210 cm) skeletons were often found in the burial mounds there; and after 1650 of the Nacazils, a sub-tribe of the Attakapas, who were a short and stocky people before their extinction about 1780. As of 1841, there were six large burial mounds at Grigsby's Bluff, size about 60 feet (18 m) wide, 20 feet (6.1 m) tall, and 100 yards (91 m) long, consisting entirely of clam and sea shells, skeletons, pottery shards, and other Native American artifacts. Between 1841 and 1901, all six of the mounds disappeared, a result of human actions. Grigsby's Bluff became a post office in 1859 (there was also a store and sawmill there), but the office was discontinued in 1893.[6]

Port Neches was the site of Fort Grigsby, a set of Civil War-era defenses intended to stop a Union advance up the Neches River. The fort was constructed in October 1862 and abandoned sometime after July 1863. Its guns, munitions, and stores were moved to the then-unfinished Fort Griffin,[7] the site of the Second Battle of Sabine Pass, often credited as the most one-sided Confederate victory of the American Civil War.

A pioneer of Port Neches was Will Block Sr., born on August 2, 1870. In 2003, his son, W. T. Block Jr., was appointed a Knight of the Royal Order of Orange-Nassau for his work in reconstructing the history of Dutch settlers in the area.[8]

The city of Port Neches was incorporated in 1902.

The greater Neches River Basin is an attraction for fishing, hunting, birding, and boating.[9]

TPC Group's Port Arthur Refinery, a chemical processing facility, was opened in 1944 by Neches Butane Products Co.[10] On November 27, 2019, two explosions occurred at the plant injuring at least eight people, three of them plant workers who were treated in hospital. Several buildings, including homes, were damaged in Port Neches and the surrounding area.[10][11] The blasts started a chemical fire that prompted a mandatory evacuation of approximately 60,000 residents from several nearby cities. The fire was finally put out on December 3 after burning for six days. The next day air monitors posted elevated levels of butadiene, prompting a second evacuation.[12][13] The explosions occurred just days after the U.S. EPA eased chemical plant safety regulations.[14]

Geography

Port Neches is located 20 miles (32 km) inland from the Gulf of Mexico at 29°58′51″N 93°57′37″W / 29.98083°N 93.96028°W (29.980863, –93.960382).[15]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 9.1 square miles (23.6 km2), of which 8.6 square miles (22.4 km2) are land and 0.50 square miles (1.3 km2), or 5.39%, are water.[4]

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1930 | 2,327 | — | |

| 1940 | 2,487 | 6.9% | |

| 1950 | 5,448 | 119.1% | |

| 1960 | 8,696 | 59.6% | |

| 1970 | 10,894 | 25.3% | |

| 1980 | 13,944 | 28.0% | |

| 1990 | 12,974 | −7.0% | |

| 2000 | 13,601 | 4.8% | |

| 2010 | 13,040 | −4.1% | |

| 2020 | 13,692 | 5.0% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[16] | |||

| Race | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| White (NH) | 10,483 | 76.56% |

| Black or African American (NH) | 283 | 2.07% |

| Native American or Alaska Native (NH) | 42 | 0.31% |

| Asian (NH) | 462 | 3.37% |

| Some Other Race (NH) | 24 | 0.18% |

| Mixed/Multi-Racial (NH) | 419 | 3.06% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 1,979 | 14.45% |

| Total | 13,692 |

As of the 2020 United States census, there were 13,692 people, 4,707 households, and 3,245 families residing in the city.

As of the census[3] of 2000, there were 13,601 people, 5,280 households, and 3,975 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,490.4 inhabitants per square mile (575.4/km2). There were 5,656 housing units at an average density of 619.8 per square mile (239.3/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 94.75% White, 0.93% African American, 0.47% Native American, 1.57% Asian, 0.01% Pacific Islander, 1.18% from other races, and 1.09% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 5.07% of the population.

There were 5,280 households, out of which 34.7% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 61.6% were married couples living together, 10.0% had a female householder with no husband present, and 24.7% were non-families. 21.4% of all households were made up of individuals, and 9.2% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.57 and the average family size was 3.00.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 25.5% under the age of 18, 8.9% from 18 to 24, 26.9% from 25 to 44, 24.3% from 45 to 64, and 14.3% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 38 years. For every 100 females, there were 96.5 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 93.9 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $47,523, and the median income for a family was $53,729. Males had a median income of $43,089 versus $27,847 for females. The per capita income for the city was $22,273. About 4.4% of families and 5.6% of the population were below the poverty line, including 5.7% of those under age 18 and 4.7% of those age 65 or over.

Education

Most of the city is served by the Port Neches–Groves Independent School District. Parts of the city fall within the Nederland Independent School District.[20]

The Effie & Wilton Hebert Public Library is the community library. It was named after Wilton Hebert, who sponsored the construction of the current library. It originated with a bookmobile service established in 1930 managed by the Tyrell Public Library of Beaumont, as the Jefferson County Commissioner's Court had requested a library for people outside of Beaumont and Port Arthur the previous year. The Jefferson County Library System established a one-room library facility between 1932 and 1934, sponsored by the Lion's Club. In 1966 the George Boyd Memorial Library, named after Port Neches city employee George Travis Boyd, opened; the Port Neches city council approved of its construction in 1964. It had a cost of $75,000 with $10,000 from the municipal government. It was across from the Port Neches city hall. The current library building had its groundbreaking on Thursday, October 15, 1981, and opened on November 12, 1982.[21]

Controversy

The Port Neches-Groves Independent School District has a long history involving its continued use of their mascot, the Indians, despite years of controversy and calls of racism. Their drill team performs wearing decorative war bonnets, their chants include the words "Scalp 'Em, Indians", their yearbook is the "War Whoop", their newspaper is called "The Pow Wow news" and their stadium is called, "The Reservation."[22]

In 2020, the Cherokee Nation requested that the school stop using their mascot, rescinding an outdated approval given to the school from 1980. Despite a nearly 150,000 signature petition requesting the name change, along with the request of the Cherokee Nation, the town voted to keep the mascot.[23]

In 2022, the Indianettes were filmed performing at Walt Disney World. According to Disney, when the school sent their audition video for approval, the Indianettes were not included and the school was instructed that their members could not wear their war bonnets during the performance. Their inclusion was not approved by Disney and was a decision made by the school. During the performance at the park, the team shouted chants of "Scalp 'Em" and enacted simulated war dances.[24] The school has not issued a statement though many residents have defended their actions and stand by their refusal to change.[25]

After the performance, Cherokee Nation's Principal Chief, Chuck Hoskin Jr, released a statement once again requesting that the school remove the mascot stating: "Port Neches-Groves Independent School District continues to use offensive and stereotypical depictions of our tribe, and this is yet again exampled by their cheer team recently in Orlando. For the past couple of years, we have written to the Port Neches superintendent and school board asking them to cease using this offensive imagery, chanting, symbolism and other practices in their school traditions as this does nothing but dishonor us and all Native American tribes who are making great strides in this country. School leaders need educating on cultural appropriateness, should apologize for continuing to ignore our requests to stop and need to make swift changes to correct these offensive displays across their school district."[26][27]

Notable people

- Andrew Dismukes, comedian and writer for Saturday Night Live is a native of Port Neches[28]

- Lee Hazlewood, country and pop singer, songwriter, and record producer

- Roschon Johnson, football player, University of Texas and Chicago Bears

- L. Q. Jones, actor and director

- Andrew Landry, professional golfer who has played on the PGA Tour since 2016

- Tex Ritter (interred at Oak Bluff Memorial Park cemetery[29])

References

- ↑ "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- 1 2 U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Port Neches, Texas

- 1 2 "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- 1 2 "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Census Summary File 1 (G001): Port Neches city, Texas". American Factfinder. U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved December 12, 2018.

- ↑ "Neches River-History and Culture".

- ↑ "Smith's Bluff and Grigsby's Bluff, Texas". Wtblock.com. Retrieved September 2, 2011.

- ↑ "Where Was Fort Grigsby? Historian May Have Answer". Wtblock.com. November 23, 1970. Retrieved September 2, 2011.

- ↑ Christine Rappleye. "That's 'Sir' W.T. Block to you guys". The Beaumont Enterprise. May 29, 2003.

- ↑ "About Port Neches". Ci.port-neches.tx.us. June 22, 2010. Archived from the original on July 4, 2011. Retrieved September 2, 2011.

- 1 2 Jacob Dick; Kim Brent; Monique Batson; Ronnie Crocker; Kaitlin Bain (November 27, 2019). "SE Texas town rocked by chemical plant explosion". Beaumont Enterprise.

- ↑ "3 hurt at Texas chemical plant hit by 2 massive explosions". Miami Herald. November 27, 2019. Retrieved November 28, 2019.

- ↑ Kennedy, Merrit (November 27, 2019). "Massive Explosion Rips Through Texas Chemical Plant". NPR. Retrieved December 9, 2020.

- ↑ "New evacuation order for Texas city hit by explosion, chemical fire". Reuters. December 5, 2019.

- ↑ Green, Miranda (November 21, 2019). "EPA finalizes rule easing chemical plant safety regulations". The Hill.

- ↑ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ↑ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ↑ "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. Retrieved May 23, 2022.

- ↑ https://www.census.gov/

- ↑ "About the Hispanic Population and its Origin". www.census.gov. Retrieved May 18, 2022.

- ↑ "2020 CENSUS - SCHOOL DISTRICT REFERENCE MAP: Jefferson County, TX" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved April 18, 2023.

- ↑ "History." Effie & Wilton Hebert Public Library. Retrieved on February 15, 2019.

- ↑ "Port Neches-Groves' performance at Walt Disney World reignites mascot controversy". 12newsnow.com. March 18, 2022. Retrieved March 21, 2022.

- ↑ Reporter, CHAD HUNTER. "CN calls for retirement of Texas school's Indian mascot". cherokeephoenix.org. Retrieved March 21, 2022.

- ↑ Skinner, Paige. "A Texas High School Drill Team Is Being Criticized For Doing A Racist Chant Against Native Americans During A Disney World Routine". BuzzFeed News. Retrieved March 21, 2022.

- ↑ Edwards, Schaefer. "Port Neches-Groves High's Cheerleaders Yell "Scalp 'em!" While Others Call Foul". Houston Press. Retrieved March 21, 2022.

- ↑ "'This does nothing but dishonor us' | Cherokee Nation Principal Chief responds to Port Neches-Groves' Disney World performance". 12newsnow.com. March 19, 2022. Retrieved March 21, 2022.

- ↑ @cherokeenation (March 18, 2022). "Register" (Tweet). Retrieved March 21, 2022 – via Twitter.

- ↑ Faye, Matt (September 17, 2020). "Port Neches native to join 'Saturday Night Live' cast". Beaumont Enterprise. Retrieved April 11, 2021.

- ↑ Stickney, Ken (January 3, 2018). ""Tex" Ritter, long gone but not forgotten". Port Arthur News. Retrieved April 11, 2021.

External links

- City of Port Neches official website

- Port Neches, Texas from the Handbook of Texas Online

- PortNechesCOOL.com, community website