In baseball statistics, slugging percentage (SLG) is a measure of the batting productivity of a hitter. It is calculated as total bases divided by at-bats, through the following formula, where AB is the number of at-bats for a given player, and 1B, 2B, 3B, and HR are the number of singles, doubles, triples, and home runs, respectively:

Unlike batting average, slugging percentage gives more weight to extra-base hits such as doubles and home runs, relative to singles. Plate appearances resulting in walks, hit-by-pitches, catcher's interference, and sacrifice bunts or flies are specifically excluded from this calculation, as such an appearance is not counted as an at-bat (these are not factored into batting average either).

The name is a misnomer, as the statistic is not a percentage but an average of how many bases a player achieves per at bat. It is a scale of measure whose computed value is a number from 0 to 4. This might not be readily apparent given that a Major League Baseball player's slugging percentage is almost always less than 1 (as a majority of at bats result in either 0 or 1 base). The statistic gives a double twice the value of a single, a triple three times the value, and a home run four times.[2] The slugging percentage would have to be divided by 4 to actually be a percentage (of bases achieved per at bat out of total bases possible). As a result, it is occasionally called slugging average, or simply slugging, instead.[3]

A slugging percentage is always expressed as a decimal to three decimal places, and is generally spoken as if multiplied by 1000. For example, a slugging percentage of .589 would be spoken as "five eighty nine," and one of 1.127 would be spoken as "eleven twenty seven."

Facts about slugging percentage

A slugging percentage is not just for the use of measuring the productivity of a hitter. It can be applied as an evaluative tool for pitchers. It is not as common but it is referred to as slugging-percentage against.[4]

In 2019, the mean average SLG among all teams in Major League Baseball was .435.[5]

The maximum slugging percentage has a numerical value of 4.000. However, no player in the history of MLB has ever retired with a 4.000 slugging percentage. Four players tripled in their only at bat and therefore share the Major League record, when calculated without respect to games played or plate appearances, of a career slugging percentage of 3.000. This list includes Eric Cammack (2000 Mets); Scott Munninghoff (1980 Phillies); Eduardo Rodríguez (1973 Brewers); and Charlie Lindstrom (1958 White Sox).[6]

Example calculation

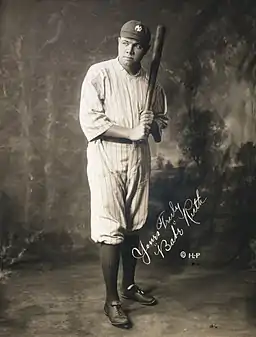

For example, in 1920, Babe Ruth played his first season for the New York Yankees. In 458 at bats, Ruth had 172 hits, comprising 73 singles, 36 doubles, 9 triples, and 54 home runs, which brings the total base count to (73 × 1) + (36 × 2) + (9 × 3) + (54 × 4) = 388. His total number of bases (388) divided by his total at bats (458) is .847 which constitutes his slugging percentage for the season. This also set a record for Ruth which stood until 2001 when Barry Bonds achieved 411 bases in 476 at bats bringing his slugging percentage to .863, which has been unmatched since.[7]

Significance

Long after it was first invented, slugging percentage gained new significance when baseball analysts realized that it combined with on-base percentage (OBP) to form a very good measure of a player's overall offensive production (in fact, OBP + SLG was originally referred to as "production" by baseball writer and statistician Bill James). A predecessor metric was developed by Branch Rickey in 1954. Rickey, in Life magazine, suggested that combining OBP with what he called "extra base power" (EBP) would give a better indicator of player performance than typical Triple Crown stats. EBP was a predecessor to slugging percentage.[8]

Allen Barra and George Ignatin were early adopters in combining the two modern-day statistics, multiplying them together to form what is now known as "SLOB" (Slugging × On-Base).[9] Bill James applied this principle to his runs created formula several years later (and perhaps independently), essentially multiplying SLOB × at bats to create the formula:

In 1984, Pete Palmer and John Thorn developed perhaps the most widespread means of combining slugging and on-base percentage: On-base plus slugging (OPS), which is a simple addition of the two values. Because it is easy to calculate, OPS has been used with increased frequency in recent years as a shorthand form to evaluate contributions as a batter.

In a 2015 article, Bryan Grosnick made the point that "on base" and "slugging" may not be comparable enough to be simply added together. "On base" has a theoretical maximum of 1.000 whereas "slugging" has a theoretical maximum of 4.000. The actual numbers do not show as big a difference, with Grosnick listing .350 as a good "on base" and .430 as a good "slugging." He goes on to say that OPS has the advantages of simplicity and availability and further states, "you'll probably get it 75% right, at least."[10]

Perfect slugging percentage

The maximum numerically possible slugging percentage is 4.000.[2] A number of MLB players (117 through the end of the 2016 season) have momentarily had a 4.000 career slugging percentage by homering in their first major league at bat.

See also

References

- ↑ "Career Leaders & Records for Slugging %". Baseball Reference. Retrieved 2014-02-27.

- 1 2 Baseball Scorekeeping: A Practical Guide to the Rules, Andres Wirkmaa, Jefferson, North Carolina, London: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2003.

- ↑ "Slugging Average All Time Leaders on Baseball Almanac".

- ↑ "What is a Slugging Percentage". MLB.com.

- ↑ "Major League Baseball Batting Year-by-Year Averages".

- ↑ "Slugging Percentage | The ARMory Power Pitching Academy". armorypitching.com. Retrieved 2020-10-10.

- ↑ "Single-Season Leaders & Records for Slugging %". Baseball Reference. Retrieved 2016-12-10.

- ↑ Lewis, Dan (2001-03-31). "Lies, Damn Lies, and RBIs". nationalreview.com. Archived from the original on 2012-10-20. Retrieved 2012-07-01.

- ↑ Barra, Allen (2001-06-20). "The best season ever?". Salon.com. Retrieved 2007-07-15.

- ↑ Separate but not quite equal: Why OPS is a "bad" statistic, Bryan Grosnick, Beyond the Box Score, September 18, 2015.