A prothallus, or prothallium, (from Latin pro = forwards and Greek θαλλος (thallos) = twig) is usually the gametophyte stage in the life of a fern or other pteridophyte. Occasionally the term is also used to describe the young gametophyte of a liverwort or peat moss as well. In lichens it refers to the region of the thallus that is free of algae.

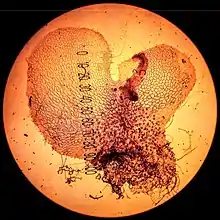

The prothallus develops from a germinating spore. It is a short-lived and inconspicuous heart-shaped structure typically 2–5 millimeters wide, with a number of rhizoids (root-like hairs) growing underneath, and the sex organs: archegonium (female) and antheridium (male). Appearance varies quite a lot between species. Some are green and conduct photosynthesis while others are colorless and nourish themselves underground as saprotrophs.

Alternation of generations

Spore-bearing plants, like all plants, go through a life-cycle of alternation of generations. The fully grown sporophyte, what is commonly referred to as the fern, produces genetically unique spores in the sori by meiosis. The haploid spores fall from the sporophyte and germinate by mitosis, given the right conditions, into the gametophyte stage, the prothallus. The prothallus develops independently for several weeks; it grows sex organs that produce ova (archegonia) and flagellated sperm (antheridia). The sperm are able to swim to the ova for fertilization to form a diploid zygote which divides by mitosis to form a multicellular sporophyte. In the early stages of growth, the sporophyte grows out of the prothallus, depending on it for water supply and nutrition, but develops into a new independent fern, which will produce new spores that will grow into new prothallia etc., thus completing the life cycle of the organism.

Theoretical advantages of alternation of generations

It has been argued that there is an important evolutionary advantages to the alternation of generations plant life-cycle.[1] By forming a multicellular haploid gametophyte rather than limiting the haploid stage to gametes, there is often only one allele for any genetic trait. Thus, alleles are not masked by a dominant counterpart (there is no counterpart).

One benefit of this is that a mutation that causes a lethal, or harmful, trait expression will cause the gametophyte to die; thus, the trait cannot be passed on to future generations, preserving the strength of the gene pool.[1] Furthermore, if individual cells of the gametophyte compete with one another, somatic mutations that reduce cell vigour may prevent a cell lineage from reproducing.[1]

In lichens

The region of the thallus in lichens that is free of algae (the photobiont partner) and contains only fungus (the mycobiont partner) is called the prothallus. It is typically white, brown, or black in colour. In crustose lichens, the prothallus is visible between areoles and on the growing thallus margin.[2] In the large genus Cladonia, the prothallus may provide a mode of vegetative reproduction, and it may have a role in stabilising the soil.[3] In some genera, such as Coenogonium, the presence of absence of prothalli is an important taxonomic character that is used to help classify species.[4] The term prothallus was first used by German botanist Georg Meyer in 1825, who introduced it in a discussion of lichen growth.[5]

References

- 1 2 3 Mable, B.K.; Otto, S.P. (1998), "The evolution of life cycles with haploid and diploid phases" (PDF), BioEssays, 20 (6): 453–462, doi:10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(199806)20:6<453::AID-BIES3>3.0.CO;2-N, S2CID 11841044

- ↑ Ulloa, Miguel; Halin, Richard T. (2012). Illustrated Dictionary of Mycology (2nd ed.). St. Paul, Minnesota: The American Phytopathological Society. p. 507. ISBN 978-0-89054-400-6.

- ↑ Hammer, Samuel (1996). "Prothallus structure in Cladonia". The Bryologist. 99 (2): 212–217. doi:10.2307/3244551. JSTOR 3244551.

- ↑ Joshi, Y (2015). "A new species and a new record of the lichen genus Coenogonium (Ostropales: Coenogoniaceae) from South Korea, with a world-wide key to crustose Coenogonium having prothalli". Mycosphere. 6 (6): 667–672. doi:10.5943/mycosphere/6/6/3.

- ↑ Mitchell, M.E. (2014). "De Bary's legacy: the emergence of differing perspectives on lichen symbiosis" (PDF). Huntia. 15 (1): 5–22 [13].