| Pygmy sperm whale[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| Individual washed ashore on Hutchinson Island, Florida | |

| |

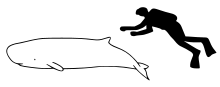

| Size compared to an average human | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Infraorder: | Cetacea |

| Family: | Kogiidae |

| Genus: | Kogia |

| Species: | K. breviceps |

| Binomial name | |

| Kogia breviceps (Blainville, 1838) | |

| |

| Pygmy sperm whale range | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Physeter breviceps | |

The pygmy sperm whale (Kogia breviceps) is one of two extant species in the family Kogiidae in the sperm whale superfamily. They are not often sighted at sea, and most of what is known about them comes from the examination of stranded specimens.

Taxonomy

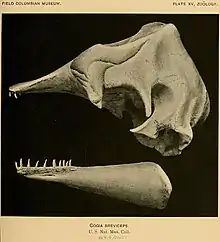

The pygmy sperm whale was first described by naturalist Henri Marie Ducrotay de Blainville in 1838. He based this on the head of an individual washed up on the coasts of Audierne in France in 1784, which was then stored in the Muséum d'histoire naturelle. He recognized it as a type of sperm whale and assigned it to the same genus as the sperm whale (Physeter macrocephalus) as Physeter breviceps. He noted its small size and nicknamed it "cachalot a tête courte"–small-headed sperm whale; further, the species name breviceps is Latin for "short-headed".[4] In 1846, zoologist John Edward Gray erected the genus Kogia for the pygmy sperm whale as Kogia breviceps, and said it was intermediate between the sperm whale and dolphins.[5]

In 1871, mammalogist Theodore Gill assigned it and Euphysetes (now the dwarf sperm whale, Kogia sima) to the subfamily Kogiinae, and the sperm whale to the subfamily Physeterinae.[6] Both have now been elevated to the family level. In 1878, naturalist James Hector synonymized the dwarf sperm whale with the pygmy sperm whale, with both being referred to as K. breviceps until 1998.[7]

Description

The pygmy sperm whale is not much larger than many dolphins. They are about 1.2 m (3 ft 11 in) at birth, growing to about 3.5 m (11 ft) at maturity. Adults weigh about 400 kg (880 lb). The underside is a creamy, occasionally pinkish colour and the back and sides are a bluish grey; however, considerable intermixing occurs between the two colours. The shark-like head is large in comparison to body size, given an almost swollen appearance when viewed from the side. A whitish marking, often described as a "false gill", is seen behind each eye.[8][9]

The lower jaw is very small and slung low.[10] The blowhole is displaced slightly to the left when viewed from above facing forward.[10] The dorsal fin is very small and hooked; its size is considerably smaller than that of the dwarf sperm whale and may be used for diagnostic purposes.[10]

Anatomy

Like its giant relative, the sperm whale, the pygmy sperm whale has a spermaceti organ in its forehead (see sperm whale for a discussion of its purpose). It also has a sac in its intestines that contains a dark red fluid. The whale may expel this fluid when frightened, perhaps to confuse and disorient predators.[11]

Dwarf and pygmy sperm whales possess the shortest rostrum of current day cetaceans with a skull that is greatly asymmetrical.[12]

Pygmy sperm whales have from 50 to 55 vertebrae, and from 12 to 14 ribs on either side, although the latter are not necessarily symmetrical, and the hindmost ribs do not connect with the vertebral column. Each of the flippers has seven carpals, and a variable number of phalanges in the digits, reportedly ranging from two in the first digit to as many as 10 in the second digit. No true innominate bone exists; it is replaced by a sheet of dense connective tissue. The hyoid bone is unusually large, and presumably has a role in the whale's suction feeding.[9]

Teeth

The pygmy sperm has between 20 and 32 teeth, all of which are set into the rostral part of the lower jaw.[13] Unusually, adults lack enamel due to a mutation in the enamelysin gene,[14] although enamel is present in very young individuals.[9]

Melon

Like other toothed whales, the pygmy sperm whale has a "melon", a body of fat and wax in the head that it uses to focus and modulate the sounds it makes.[15] The inner core of the melon has a higher wax content than the outer cortex. The inner core transmits sound more slowly than the outer layer, allowing it to refract sound into a highly directional beam.[16] Behind the melon, separated by a thin membrane, is the spermaceti organ. Both the melon and the spermaceti organ are encased in a thick fibrous coat, resembling a bursa.[17] The whale produces sound by moving air through the right nasal cavity, which includes a valvular structure, or museau de singe, with a thickened vocal reed, functioning like the vocal cords of humans.

Stomach

The stomach has three chambers. The first chamber, or forestomach, is not glandular, and opens directly into the second, fundic chamber, which is lined by digestive glands. A narrow tube runs from the second to the third, or pyloric, stomach, which is also glandular, and connects, via a sphincter, to the duodenum. Although fermentation of food material apparently occurs in the small intestine, no caecum is present.[18]

Brain

The rostroventral dura of the brain contains a significant concentration of magnetite crystals, which suggests that K. breviceps can navigate by magnetoreception.[9]

Studies have also shown that compared to the sperm whale, the pygmy sperm whale brain has significantly fewer neurons, which may be connected to a decreased complexity in social interaction and group-based living.[19]

Echolocation

Like all toothed whales, the pygmy sperm whale hunts prey by echolocation. Sound produced for echolocation by many odontocetes come in the form of high-frequency clicks.[20] The frequencies it uses are mostly ultrasonic,[16] peaking around 125 kHz.[20] The clicks from their echolocation has been recorded to last an average of 600 microseconds. When closing in on prey, the click repetition rate starts at 20 Hz and then begins to rise when nearing the target.[20]

The pulse sounds that pygmy sperm whales make for echolocation are generated primarily from the museau de singe or monkey's muzzle, which is an anatomical structure located within the whale's skull that produces sound when air passes through its lips.[16] The sound from the museau de singe is transferred to the attached cone of the spermaceti organ. Unique from other odontocetes, the spermaceti organ contacts the posterior of the whale's melon.[16] Fat from the core of the spermaceti organ helps direct sonic energy from the museau de singe to the melon.[16] The melon acts as a sonic magnifier and gives directionality to sound pulses, making echolocation more efficient. Fat on the interior of the melon has a lower molecular weight lipid than the surrounding outer melon.[16] Since the sound waves move from a lower velocity material to a higher one during sound production, the sound undergoes inward refraction and becomes increasingly focused. Variation in fat density within the melon ultimately contributes to the production of highly directional, ultrasonic sound beams in front of the melon. The combined melon and spermaceti organ system cooperate to focus echolocative sounds.

Like in most odontocetes, the known echoreception apparatus used by the pygmy sperm whale is linked to the fat-filled lower mandibles within the skull.[16] However, compositional topography of the pygmy sperm whale's skull indicates abnormally large fatty jowls surrounding the mandibles, suggesting a more intricate echoreception apparatus.[16] Additionally, an unusual cushion structure, of porous and spongy texture, found behind the museau de singe has been hypothesized of being a possible "pressure receptor".[16] The positioning of this cushion structure in close proximity to the largest cavities closest to the museau de singe may suggest that it is a sound absorber used for echoreception.

Reproduction

Although firm details concerning pygmy sperm whale reproduction are limited, they are believed to mate from April to September in the Southern Hemisphere and March to August in the Northern Hemisphere.[9] These whales become sexually mature at age 4-5, and like virtually all mammals, are iteroparous (reproducing many times during their lives). Once a female whale is impregnated, the average gestation period lasts 9–11 months, and unusually for cetaceans, the female gives birth to a single calf head-first.[21] Newborn calves are about 1.2 metres (3 ft 11 in) in length, weighing 50 kg, and are weaned around one year of age.[9] They are believed to live up to age 23.

Behaviour

The whale makes very inconspicuous movements. It rises to the surface slowly, with little splash or blow, and remains there motionless for some time. In Japan, the whale was historically known as the "floating whale" because of this. Its dive is equally lacking in grand flourish - it simply drops out of view. The species has a tendency to back away from rather than approach boats. Breaching has been observed, but is not common. [22] [23]

Pygmy sperm whales are normally either solitary or found in pairs,[24] but have been seen in groups up to six.[25] Dives have been estimated to last an average of 11 minutes, although longer dives up to 45 minutes have been reported.[9] The ultrasonic clicks of pygmy sperm whales range from 60 to 200 kHz, peaking at 125 kHz,[20] and the animals also make much lower-frequency "cries" at 1 to 2 kHz.[26]

Diet/foraging behavior

Analysis of stomach contents suggests that pygmy sperm whales feed primarily on cephalopods, most commonly including bioluminescent species found in midwater environments. Most of the cephalopod hunting is known to be pelagic, and fairly shallow, within the first 100 m of the surface.[27] The most common prey are reported to include glass squid, and lycoteuthid and ommastrephid squid, although the whales also consume other squid, and octopuses. They have also been reported to eat some deep-sea shrimps, but, compared with dwarf sperm whales, relatively few fish.[9]

Predators may include great white sharks[28] and killer whales.[29]

Pygmy sperm whales and dwarf sperm whales are unique among cetaceans in using a form of "ink" to evade predation in a manner similar to squid. Both species have a sac in the lower portion of their intestinal tracts that contains up to 12 liters of dark reddish-brown fluid, which can be ejected to confuse or discourage potential predators.[30]

Population and distribution

Pygmy sperm whales are found throughout the tropical and temperate waters of the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans,[9] and occasionally among colder waters such as off Russia.[31][32] However, they are rarely sighted at sea, so most data come from stranded animals - making a precise range and migration map difficult. They are believed to prefer off-shore waters, and are most frequently sighted in waters ranging from 400 to 1,000 m (1,300 to 3,300 ft) in depth, especially where upwelling water produces local concentrations of zooplankton and animal prey.[33] Their status is usually described as rare, but occasional patches of higher-density strandings suggest they might be more common than previously estimated. The total population is unknown.

Fossils identified as belonging to K. breviceps have been recovered from Miocene deposits in Italy, Japan, and southern Africa.[9]

Human interaction

Pygmy sperm whales have never been hunted on a wide scale. Land-based whalers have hunted them from Indonesia, Japan, and the Lesser Antilles. This species was impacted by whaling in the 18th and 19th centuries, as sperm whales were especially sought after by whalers for their sperm oil, produced by the spermaceti organ. The oil was used to fuel kerosene lamps. Ambergris, a waste product produced by the whales, was also valuable to whalers as it was used by humans in cosmetics and perfume.[34]

They were not as heavily hunted as their larger counterpart Physeter macrocephalus, the sperm whale, which are typically 120,000 lb, thus preferred by whalers.[35] The pygmy sperm whale is also rather inactive and slow rising when coming to the surface and as such do not bring much attention to themselves. However, they were easy targets, as they tended to swim slowly and lie motionless at the surface.[36]

Individuals have also been recorded killed in drift nets. Some stranded animals have been found with plastic bags in their stomachs, which may be a cause for concern. Whether these activities are causing long-term damage to the survival of the species is not known.

Pygmy sperm whales do not do well in captivity.[37][38] The longest recorded survival in captivity is 21 months, and most captive individuals die within one month, mostly due to dehydration or dietary problems.[39]

Pygmy sperm whales have been reported as being forced to change their diets and foraging behaviors due to anthropological factors such as deep-sea trawling and increased fishing for cephalopods off the coast of many Southeast Asian countries. [27]

Conservation

In 1985, the International Whaling Commission ended sperm whaling.[36]

The pygmy sperm whale is covered by the Agreement on the Conservation of Small Cetaceans of the Baltic, North East Atlantic, Irish and North Seas (ASCOBANS)[40] and the Agreement on the Conservation of Cetaceans in the Black Sea, Mediterranean Sea and Contiguous Atlantic Area (ACCOBAMS).[41] The species is further included in the Memorandum of Understanding Concerning the Conservation of the Manatee and Small Cetaceans of Western Africa and Macaronesia (Western African Aquatic Mammals MoU)[42] and the Memorandum of Understanding for the Conservation of Cetaceans and Their Habitats in the Pacific Islands Region (Pacific Cetaceans MoU).[43]

As not much is known about this species, as well as due to the whaling and conservation laws in place for marine mammals, it is listed as “lower risk least concern” in the IUCN Red list.[36] However, it faces some modern day issues; it is one of the most common stranded species in Florida sound. Due to its slow-moving and quiet nature, the species is at a higher risk of boat strikes.[44] Its small size also allows for it to become a byproduct of commercial fishing, caught in seine nets.[36] Anthropogenic noise caused by military activity and shipping is another issue affecting this species, as it echolocates. Pygmy sperm whales have also repeatedly been found stranded with plastic in their stomachs.[44]

Specimens

- MNZ MM002651, collected Hawke's Bay, New Zealand, no date data

See also

References

- ↑ Mead, J. G.; Brownell, R. L. Jr. (2005). "Order Cetacea". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 737. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ↑ Kiszka, J.; Braulik, G. (2020). "Kogia breviceps". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T11047A50358334. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-2.RLTS.T11047A50358334.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ↑ "Appendices | CITES". cites.org. Retrieved 2022-01-14.

- ↑ de Blainville, M. H. (1838). "Sur les Cachalot" [On the Sperm Whales]. Annales Françaises et Étrangères d'Anatomie et de Physiologie (in French). 2: 335–337.

- ↑ Gray, J. E. (1846). "Zoology of the Voyage of H. M. S. Erebus & Terror Under the Command of Captain Sir James Clark Ross, R. N., F. R. S., During the Years 1839 to 1843". Mammalia. 1: 22.

- ↑ Gill, T. (1871). "The Sperm Whales, Giant and Pygmy". American Naturalist. 4 (12): 725–743. doi:10.1086/270684.

- ↑ Rice, D. W. (1998). Marine Mammals of the World: Systematics and Distribution (PDF). Society for Marine Mammalogy. pp. 83–84. ISBN 978-1-891276-03-3.

- ↑ Roest, A.I. (1970). "Kogia simus and other cetaceans from San Luis Obispo County, California". Journal of Mammalogy. 51 (2): 410–417. doi:10.2307/1378507. JSTOR 1378507.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Bloodworth, B.E. & Odell, D.K. (2008). "Kogia breviceps (Cetacea: Kogiidae)". Mammalian Species. 819: Number 819: pp. 1–12. doi:10.1644/819.1.

- 1 2 3 "Pygmy Sperm Whale". www.acsonline.org. Retrieved 2022-04-06.

- ↑ Scott, M.D. & Cordaro, J.G. (1987). "Behavioral observations of the dwarf sperm whale, Kogia simus". Marine Mammal Science. 3 (4): 353–354. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.1987.tb00322.x.

- ↑ Mcalpine, Donald F. "Pygmy and dwarf sperm whales: Kogia breviceps and K. sima." Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals (Second Edition). 2009. 936-938.

- ↑ Bloodworth Brian E., Odell Daniel K. (2008). "Kogia breviceps". Mammalian Species. 819: 1–12. doi:10.1644/819.1.

- ↑ Meredith, R. W.; Gatesy, J.; Cheng, J.; Springer, M. S. (2010). "Pseudogenization of the tooth gene enamelysin (MMP20) in the common ancestor of extant baleen whales". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 278 (1708): 993–1002. doi:10.1098/rspb.2010.1280. PMC 3049022. PMID 20861053.

- ↑ Clarke, M.R. (2003). "Production and control of sound by the small sperm whale, Kogia breviceps and K. sima and their implications for other Cetacea". Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. 83 (2): 241–263. doi:10.1017/S0025315403007045h. S2CID 84103043.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 R., Karol; C., Litchfield; D., Caldwell; M., Caldwell (1978). Compositional topography of melon and spermaceti organ lipids in the pygmy sperm whale Kogia breviceps: Implications for echolocation. Marine Biology , Volume 47 (2)

- ↑ Cranford, T.W.; et al. (1996). "Functional morphology and homology in the odontocete nasal complex: implications for sound generation". Journal of Morphology. 228 (2): 223–285. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-4687(199606)228:3<223::AID-JMOR1>3.0.CO;2-3. PMID 8622183. S2CID 35653583.

- ↑ Hagey, L.R.; et al. (1993). "Biliary bile acid composition of the Physeteridae (sperm whales)". Marine Mammal Science. 9 (1): 23–33. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.1993.tb00423.x.

- ↑ Poth, Fung, Gunturkun, Ridgway (2005-02-25). "Neuron numbers in sensory corticies of five delphinids compared to a physterid, the pygmy perm whale". Brain Research Bulletin. 66 (357–360): 357–360. doi:10.1016/j.brainresbull.2005.02.001. PMID 16144614. S2CID 14822113.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - 1 2 3 4 Marten, K. (2000). "Ultrasonic analysis of pygmy sperm whale (Kogia breviceps) and Hubbs' beaked whale (Mesoplodon carlhubbsi) clicks" (PDF). Aquatic Mammals. 26 (1): 45–48.

- ↑ Huckstadt, L.A. & Antezana, T. (2001). "An observation of parturition in a stranded Kogia breviceps". Marine Mammal Science. 17 (2): 362–365. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.2001.tb01277.x.

- ↑ Culik, Boris M. (2011). Odontocetes - The Toothed Whales (PDF). Bonn, Germany: CMS. pp. 74–76. ISBN 978-3-937429-92-2. Retrieved 27 January 2022.

- ↑ Flood, Robert. "Pygmy Sperm Whale, breaching, from Cadiz to Lanzarote ferry, North Atlantic, 5th September 2018". YouTube. Retrieved 27 January 2022.

- ↑ Willis, P.M. & Baird, R.W. (1998). "Status of the dwarf sperm whale, Kogia simus, with special reference to Canada". Canadian Field-Naturalist. 112 (1): 114–125.

- ↑ Lundrigan, Barbara; Myers, Allison (2002-09-04). "Kogia breviceps (pygmy sperm whale)". Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 2021-12-08.

- ↑ Thomas, J.A.; et al. (1990). "A new sound from a stranded pygmy sperm whale" (PDF). Aquatic Mammals. 16 (1): 28–30.

- 1 2 Beatson, Emma (21 April 2007). "The diet of pygmy perm whales, Kogia breviceps, stranded in New Zealand: implications for conservation". Rev Fish Biol Fisheries. 10 (1007).

- ↑ Long, D.J. (1991). "Apparent predation by a white shark Carcharadon charcharias on a pygmy sperm whale Kogia breviceps" (PDF). Fishery Bulletin. 89 (3): 538–540.

- ↑ Dunphy-Daly, M.M.; et al. (2008). "Temporal variation in dwarf sperm whale (Kogia sima) habitat use and group size off Great Abaco Island, Bahamas". Marine Mammal Science. 24 (1): 171–182. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.2007.00183.x.

- ↑ "Pygmy sperm whale (Kogia breviceps)". NOAA Fisheries Office of Protected Resources web site. NOAA. 2014-10-20. Archived from the original on 2013-10-03. Retrieved 2015-01-11.

- ↑ ХОРОШИЕ НОВОСТИ ПРО ЖИВОТНЫХ. 2017. НА КУНАШИРЕ (КУРИЛЫ) СПАСЛИ ЗАСТРЯВШЕГО НА МЕЛИ РЕДКОГО КАШАЛОТА С ДЕТЕНЫШЕМ. Retrieved on September 26, 2017

- ↑ 2017. НА КУНАШИРЕ (КУРИЛЫ) СПАСЛИ ЗАСТРЯВШЕГО НА МЕЛИ РЕДКОГО КАШАЛОТА С ДЕТЕНЫШЕМ. Retrieved on September 26, 2017

- ↑ Davis, R.W.; et al. (1998). "Physical habitat of cetaceans along the continental slope in the north-central and western Gulf of Mexico". Marine Mammal Science. 14 (3): 490–607. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.1998.tb00738.x.

- ↑ Davis, Lance E.; Gallman, Robert E.; Gleiter, Karin (January 1997). In Pursuit of Leviathan: Technology, Institutions, Productivity, and Profits in American Whaling, 1816-1906. University of Chicago Press. pp. 20–56. ISBN 978-0-226-13789-6.

- ↑ Davis, Lance E.; Gallman, Robert E.; Gleiter, Karin (January 1997). In Pursuit of Leviathan: Technology, Institutions, Productivity, and Profits in American Whaling, 1816-1906. University of Chicago Press. pp. 20–56. ISBN 978-0-226-13789-6.

- 1 2 3 4 Willis, P. M.; Baird, R. W. (1998). "Status of the dwarf sperm whale, Kogia simus, with special reference to Canada". Canadian Field-Naturalist. 112 (1): 114–125.

- ↑ Loranger, Linda (3 December 1991). "Pygmy Sperm Whale Dies In Mystic After Record Time In Captivity". Hartford Courant. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

- ↑ Klingener, Nancy (2 November 2000). "Pygmy Whale Snags Fence, Dies After Four Months In Captivity". Sun Sentinel. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

- ↑ Manire, C.A.; et al. (2004). "An approach to the rehabilitation of Kogia spp". Aquatic Mammals. 30 (2): 257–270. doi:10.1578/AM.30.2.2004.257.

- ↑ Official website of the Agreement on the Conservation of Small Cetaceans of the Baltic, North East Atlantic, Irish and North Seas

- ↑ Official website of the Agreement on the Conservation of Cetaceans in the Black Sea, Mediterranean Sea and Contiguous Atlantic Area

- ↑ Memorandum of Understanding Concerning the Conservation of the Manatee and Small Cetaceans of Western Africa and Macaronesia

- ↑ Official webpage of the Memorandum of Understanding for the Conservation of Cetaceans and Their Habitats in the Pacific Islands Region

- 1 2 Scott, Michael D.; Campbell, Walton B.; Whitaker, Brent R.; Nicolas, John R.; Westgate, Andrew J.; Hohn, Aleta A. (January 2001). "A note on the release and tracking of a rehabilitated pygmy sperm whale (Kogia breviceps)". Journal of Cetacean Research and Management. 3 (1): 87–94.

Further reading

- Pygmy and Dwarf Sperm Whales by Donald F. McAlpine in Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals pp. 1007–1009 ISBN 978-0-12-551340-1

- Whales Dolphins and Porpoises, Mark Carwardine, Dorling Kindersley Handbooks, ISBN 0-7513-2781-6

- National Audubon Society Guide to Marine Mammals of the World, Reeves, Stewart, Clapham and Powell, ISBN 0-375-41141-0