Pylyp Orlyk's March on the Right-bank Ukraine (Ukrainian: Похід Пилипа Орлика на Правобережну Україну) was the military campaign of the Hetman Pylyp Orlyk on the Right-bank Ukraine in January–March 1711 in order to liberate its territory from Moscow's troops and to restore the hetman's power.

Due to improper training, bad timing and betrayal of Tatar allies, the campaign ended in the defeat of Orlyk's troops and led to the loss of support for the hetman among the Ukrainian population.

Preconditions

The defeat of Swedish and Cossack troops near Poltava, the punitive expedition of Moscow troops to Ukraine and the destruction of the Zaporozhian Sich, which took place in 1709, radically changed the balance of forces in Ukraine. After the military defeat, hetman Ivan Mazepa together with Cossack starshyna (senior Cossack officers) were forced to emigrate to Bendery (modern Tighina, Moldova), the Ottoman Empire territory, where he died in September 1709.

Six months after Mazepa's death, on April 5, 1710, in Bendery, Pylyp Orlyk was elected as the new hetman in exile. The election took place in the presence of Zaporozhian Cossacks and general starshyna, as well as the Turkish sultan and the Swedish king.

Charles XII, even after his defeat near Poltava, did not intend to abandon his efforts in Eastern Europe, and planned a new operation aimed at consolidating Ukraine under Pylyp Orlyk, and Poland under Stanisław Leszczyński. Right-bank Ukraine, and in part Left-bank and Slobozhanshchyna, were to become the field of the action that, if successful, would have to be extended to Poland.

The Ottoman authorities, concerned about Russia's approach to their borders, also fully supported this operation. With the support of Charles XII, Pylyp Orlyk entered into an alliance with the Crimean Tatars and the Ottoman Empire, and on November 8, 1710, the latter, supporting hetman Orlyk, declared war on Russia.

The Turkish army started the march led by the grand vizier Numan Pasha. However, the troops moved very slowly, and reached the Danube river only in mid-June 1711.

The created union included Zaporozhian Cossacks, Swedes and Tatars. Prior to the campaign, the Cairo Treaty of defensive-offensive military alliance was signed between the exile government of Pylyp Orlyk and the Crimean Khanate.[1] Orlyk's significant diplomatic merit was that he managed to oblige the Tatars not to take yasir — prisoners, not to rob churches and not to commit violence when entering Ukrainian territory.[2][3]

Raid of Tatars on Slobozhanshchyna

As part of the general plan, in January 1711 the Tatar khan Devlet Giray went to Slobozhanshchyna with his main forces (approximately 50,000 members of the Crimean horde) and several hundreds of Cossacks.[4]

The Crimean army in Slobozhanshchyna felt almost no resistance. Small garrisons in the fortified towns and cities of the Kharkiv Regiment could not hold out. General Shidlovsky, who was tasked with defending Slobozhanshchyna from the Tatars, had not even arrived in Kharkiv yet.[5] The locals and the Cossacks were partly intimidated, partly just not hostile to the Tatars, especially when seeing Zaporozhian Cossacks among the Tatar ranks.[6]

For example, the town of Vodolahy of the Kharkiv Regiment did not resist — on the contrary, people brought bread and salt to the Tatars; others, like Merefa and Taranivka, tried to defend themselves but were seized.[7]

Before reaching Kharkiv, the khan suddenly turned back to the Samara River, where he laid siege to two fortified fortresses: Novoserhiivska and Novobohorodytska. The Novoserhiiv Cossacks and their officers surrendered to the Tatars voluntarily, handing over the Moscow garrison of the city: one captain and 80 soldiers.[7] The garrison of the Novobohorodytska fortress stubbornly defended itself, so that the khan had to lift the siege.[8]

Initially gaining a foothold near Samara, the khan moved back: according to the correspondence from Bendery, on March 13 (24) he was already in Crimea.[9] On his way back, Devlet Giray left about 1,000 Cossack-Tatar guards near Samara and a small garrison in the Novoserhiivska Fortress, promising to return to Ukraine in spring.

Immediately after the retreat of the Tatars, hetman of the Left-bank Ukraine Ivan Skoropadsky occupied this important outpost in the South East, and the Cossacks who voluntarily joined the Crimean khan were executed.[8]

The Tatar raid had a detrimental effect on Orlyk's reputation — after the Tatar invasion, the hetman could not count on any support from the residents of the Left-bank Ukraine and Slobozhanshchyna.

Main campaign

The Swedish king undertook to wage war until Ukraine was liberated from Moscow rule, and the Turks and Tatars pledged their help in this effort. Pylyp Orlyk was well prepared for the campaign. He sent letters-universals with calls for revolt against the power of the Moscow tsar. The people supported Orlyk, and one by one the cities of the Right-bank Ukraine came under the rule of the hetman. Pylyp Orlyk also sent a letter with calls for fight to the hetman of the Left-bank Ukraine Ivan Skoropadsky, which greatly frightened the Moscow government and Peter I.

Onset of Troops

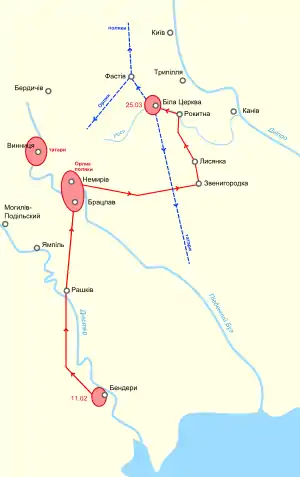

On February 11 or 12, 1711,[10] Pylyp Orlyk started the main part of the campaign, and the army left Bendery. The Tatar part of the army consisted of the Budjak and Bilhorod hordes (20,000-30,000 people), led by the Crimean khan's son, Sultan Galga (Kalga Sultan). The Poles (supporters of Stanisław I Leszczyński) acted under the command of Kyiv voivode Józef Potocki[10] and headman Galecki. Cossacks were under the command of Kost Hordiienko. Poles and Cossacks together had 6-7 thousand of people.[11] There was also a small number of Swedes in the army (around 30 officers). Pylyp Orlyk was the commander-in-chief and Charles XII accompanied the army for some time before returning to Bendery.

On the Right Bank

Near Rashkiv, the army moved to the territory of the Right Bank of Ukraine and quickly began to move forward. Józef Potocki insisted on advancing towards Lithuania.[10] In the first half of February the army was located in a wide area between Nemyriv, Bratslav and Vinnytsia: Kalga Sultan settled in Vinnytsia; Cossacks and Poles were concentrated near Nemyriv.[12] There was no resistance from the Moscow-Cossack forces: general Volkonsky and his subordinate general Vidman, who stood on the borders of Moldavia, were falling back without a fight, first guarding Kamianets and later retreating through Berdychiv to Kyiv. In the second half of February, the alliance army was resting after the quick move.[12]

In this phase of the campaign the situation was very good for Orlyk. Society and almost all Right-bank regiments, with the exception of a few hundreds of the Bila Tserkva Regiment, joined his army. The Moscow authorities were very concerned about the course of events.[13]

The important prerequisite of the positive reaction from the people was not only dissatisfaction with the Moscow authorities and their colonels, but also the fact that a large and diverse army did not allow for bullying and looting.[14] This was a great achievement of Pylyp Orlyk, who understood that the success of the whole campaign depended on it.[15]

At this stage of the campaign, supplies for the army were sufficient: people voluntarily supplied soldiers with fodder and provisions, the sultan also brought some supplies with him.

Fight near Lysianka

In late February or early March, the alliance army continued the move. It was headed to the only still respected Moscow outpost on the Right Bank of Ukraine — Bila Tserkva. The route ran first to the east, to Zvenyhorodka, and from there — to the northwest, to the river Ros.[16] The goal was, obviously, to seize the whole Right-bank Ukraine all the way to the Dnieper river: for that the capture of the Bila Tserkva was essential.

An army under the command of general osavul Stepan Butovych opposed Pylyp Orlyk's troops and was defeated in the battle near Lysianka, the osavul himself was taken prisoner. The hetman was supported by the revolted Ukrainian people.[17]

The victory near Lysyanka had a significant resonance. Ukrainian cities, including the regimental Bohuslav and Korsun, surrendered without a fight. Mazepa's successor was supported in his quest to extend his power to the Right Bank by colonel Samiilo Ivanovych (Samus) of the Bohuslav Regiment, colonel Andrii Kandyba of the Korsun Regiment, colonel Ivan Popovych of the Uman Regiment, and colonel Danylo Sytynskyi of the Kaniv Regiment. This was facilitated by Pylyp Orlyk's letters-universals "to the militant maloros people" with a call to oppose the Moscow tsar. One of them was issued by the hetman on March 9, 1711, in Lysianka.

Pylyp Orlyk's universals were known throughout the Right-Bank Ukraine and were distributed up to and including the Pereiaslav Regiment lands. Impressed by the successful combat maneuvers and the transition of the Cossack rulers to his side, the hetman informed King Charles XII of Sweden that his army had grown more than fivefold.

The Siege of Bila Tserkva

After the victory near Lysianka, the road to Bila Tserkva was cleared. This time the army moved slowly so that it reached Bila Tserkva region around March 18.

While advancing in the Syniava — Rokytne area, the army started to experience problems with provisions — hence the requisitions of the population intensified. As a result, the discipline was shaken — not only Tatars but also Poles allowed themselves violence against the civilian population.[18]

In such difficult conditions, the army spent another week crossing the Ros — the dam and the bridge near Syniava were destroyed, and the help of the locals was needed.[19]

The siege of Bila Tserkva started on March 25. The city was well fortified, it housed the Moscow garrison. The fortress was well supplied with everything necessary to keep the siege; shortly before the arrival of the Orlyk's army, ammunition and provisions were delivered.[20] The garrison of Bila Tserkva was quite small: it consisted of 500 Russians under the command of Colonel Annenkov, and parts of the Bila Tserkva Cossacks of Colonel Tansky, loyal to the Moscow tsar.[21] Orlyk's forces at that time numbered about 10,000 Zaporozhian Cossacks and the Right-bank Cossacks who joined him, as well as Tatars and Poles.[22]

The siege of the city began, but the number of attackers did not play a significant role in this process: the Tatar-Polish cavalry could not help in the siege, and it all depended on whether Orlyk managed to seize the fortress with the technical means he had at his disposal. There was almost no artillery in Orlyk's army; there were only 4 or 5 canons.[7] It was not possible to achieve the desired effect with the existing resources.

Despite the besieging of the town, the garrison of the fortress successfully repulsed all the attacks by Orlyk's army. Twice during the second and third days of the siege the Cossacks tried to attack the castle after gaining a foothold in the lower part of the town and making sconces, but were unsuccessful both times.[23] None of the assaults were effective, as the garrison had sufficient ammunition and strong artillery.

Betrayal by the Tatars

Three days of the siege (March 25–27) resulted in nothing. The discontent of the Tatars was growing — the young and inexperienced sultan could not restrain the horde, who was demanding permission to take yasir.[24] The dissatisfaction of the Tatars on one hand was amplified by the lack of provisions for people and horses, and on the other — by the approach of spring, melting snow and flooding of rivers, which nullified the mobility of Tatar troops in the event of Moscow army's attack.[7]

Seeing no progress in storming the fortress, the Tatar army withdrew, spreading its troops almost to the Dnieper river, and moved south to the Bug river, taking yasir and destroying settlements.[24] Orlyk rushed after them, begging the sultan to return or give him at least 10,000 Tatars to continue the war, but received a refusal.

The Tatars' betrayal had catastrophic consequences for the whole campaign: the Right-bank Cossacks, who joined Orlyk, learned that Tatars were plundering villages and towns and taking people as prisoners so they rushed to save their loved ones.[25] The army was getting smaller by the hour.

The Retreat of Orlyk's Army

As a result of the catastrophic decrease of the army numbers, the siege of Bila Tserkva had to be stopped, and the remnants of the army were withdrawn to Fastiv. The Poles then went in the direction of Polissya, and Pylyp Orlyk with 3 thousand soldiers returned to Bendery — the starting point of the campaign.[26]

Prince M. Golitsyn's Moscow division, advancing from Kyiv through Trypillia to Bila Tserkva, did not arrive in time to take part in the events. Only Volkonsky's unit was able to fight off a large number of prisoners from some Tatar detachment.[27]

Consequences

The failure of the campaign had severe consequences for Orlyk himself and for the Ukrainian-Swedish vector he pursued. The hetman's reputation among the population of Right-bank Ukraine was destroyed by Tatars' actions, and the hopes for support from the Left Bank and Slobozhanshchyna were also lost due to the planned Tatar raid that started in January.

The hetman tried to heal the wounds inflicted by the Tatars on the Right Bank of Ukraine — he asked the Turkish sultan to return captured Ukrainians, which was ordered to do.[28]

As early as spring of 1711, the Moscow army led by Boris Sheremetev started the movement towards the area between Dniester and Prut rivers, thus beginning the Prut campaign of 1711. Pylyp Orlyk and Zaporozhian Cossacks also took part in the Prut campaign in summer of 1711 on the Turkish side.

References

- ↑ Кресін Олексій Веніамінович. Політико-правові аспекти відносин урядів Івана Мазепи та Пилипа Орлика з Кримським ханством

- ↑ Костомаровъ «Мазепа и Мазепинцы», С.-Петербургъ 1885, стор. 629

- ↑ Переписка Орлика й інших діячів походу в Чтен. Импер. Москов. Истор. Обід. 1847, No. 1, с. 47—49.

- ↑ Д. И. Эварницкій: «Исторія запорожскихъ казаковъ», С.-Петербургь 1897, т. III, стор. 494.

- ↑ Мышлаевскій: «Сборникъ военно-историческихъ матеріалов», С.-Петербургъ 1898, с. 54

- ↑ Мышлаевскій: «Сборникъ военно-историческихъ матеріалов», С.-Петербургъ 1898, с. 13, 49

- 1 2 3 4 Кореспонденція з Бендер (анонімна) з 6(16) травня 1711 — Preuss. Geh. St.-flr. Rep. XI. Russland 22a— додаток до реляції пруського резидента у Відні з 27 червня н. ст. 1711 р.

- 1 2 Д. И. Эварницкій: «Исторія запорожскихъ казаковъ», С.-Петербургь 1897, т. III, с. 496

- ↑ генерал Шидловський у своїм донесенню до адмірала Aпраксіна з 12 березня каже, що татарський хан пішов від Самари до Криму 5 березня (Сбор. воєнно.-истор. мат., стор. 54)

- 1 2 3 Gierowski Józef A. Orlik Filip h. Nowina (1672—1742) // Polski Słownik Biograficzny.— Wrocław — Warszawa — Kraków — Gdańsk: Zakład Narodowy Imienia Ossolińskich, Wydawnictwo Polskiej Akademii Nauk, 1979. — Tom XXIV/1, zeszyt 100. — S. 198. (in Polish)

- ↑ Пилип Орлик на Правобережній Україні в 1711 р. — Д-р. Б. Крупницький (За державність No. 4, 1934)

- 1 2 Фельдмаршалъ графъ Б. П. Шереметевъ: «Военно-походный журналъ 1711 и 1712 г. г.», С.-Петербургъ, 1898. — С. 12.

- ↑ Костомаровъ. «Мазепа и Мазепинцы». — С.-Петербургъ, 1885. — С. 631.

- ↑ Арх. Юг.-Зап. Рос, III—2, с. 188

- ↑ Мышлаевскій. «Сборникъ военно-историческихъ матеріалові». — С.-Петербургъ 1898. — С. 49.

- ↑ Переписка Орлика й інших діячів походу в Чтен. Импер. Москов. Истор. Обід. 1847, No. 1, с. 66

- ↑ "Модзалевский В.Л. Малороссийский Родословник. – Т. 1: А–Д. – К., 1908. – 541 с." (PDF).

- ↑ Переписка Орлика й інших діячів походу в Чтен. Импер. Москов. Истор. Обід. 1847, No. 1, с. 58

- ↑ Переписка Орлика й інших діячів походу в Чтен. Импер. Москов. Истор. Обід. 1847, No. 1, с. 68

- ↑ Aрх. Юго-Западн. Рос, III—2, стор. 749.

- ↑ Мышлаевскій: «Сборникъ военно-историческихъ матеріалові», С.-Петербургъ 1898, с. 229.

- ↑ Мышлаевскій: «Сборникъ военно-историческихъ матеріалові», С.-Петербургъ 1898, с. 231.

- ↑ Мышлаевскій: «Сборникъ военно-историческихъ матеріалові», С.-Петербургъ 1898, с. 230 і далі

- 1 2 Переписка Орлика й інших діячів походу в Чтен. Импер. Москов. Истор. Обід. 1847, No. 1, с. 38

- ↑ Костомаров «Мазепа и Мазепинцы», С.-Петербургь 1855, стор. 634.

- ↑ Костомаров «Мазепа и Мазепинцы», С.-Петербургь 1855, стор. 632

- ↑ Мышлаевскій: «Сборникъ военно-историческихъ матеріалові», С.-Петербургъ 1898, с. 73, 79, 82.

- ↑ Переписка Орлика й інших діячів походу в Чтен. Импер. Москов. Истор. Обід. 1847, No. 1, с. 42