Prince Pyotr Borisovich Kozlovsky | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) from portrait by Karl Pol, 1838 | |

| Born | December 1783 Moscow |

| Died | 26 October 1840 (aged 56) Baden Baden |

| Occupation(s) | diplomat, writer |

| Spouse | Giovanetta Rebora |

| Children | Sophia (Sofka) Koslowska (1817–1878), Charles Kozlovski |

| Parent(s) | Boris Petrovich Kozlovsky (1754–1809), Anna Nikolayevna Bologovskaya (1762–1811) |

Prince Pyotr Borisovich Kozlovsky (Russian: Пётр Бори́сович Козло́вский, December 1783 in Moscow – 26 October 1840 in Baden-Baden) was a Russian diplomat and a man of letters.

Biography

A member of one of Russia's Rurikid families, Pyotr Borisovich Kozlovsky had a short career as a diplomat, was a writer and translator, but is known mainly for his contacts with the numerous literary figures with whom he became acquainted during his extensive and protracted travels in Western Europe.

His early intellectual development was greatly aided by contact with the cultivated foreigners, primarily French emigrants, who were frequent visitors to his parental home. He received an education at home, though this was not taken seriously until the death of an older brother. Kozlovsky became a fluent speaker of French, English, German, and Italian.

Enjoying the patronage of Prince Alexander Borisovich Kurakin, in 1801 he entered the Russian diplomatic service in St. Petersburg and in 1802 was appointed interpreter to the Russian mission to the Kingdom of Sardinia. Initially in Rome, where he developed his interest in mathematics and physics, Kozlovsky followed the Sardinian court to Cagliari, when it was forced to flee Rome in 1806. By 1810, he had been promoted to chargé d'affaires.

Recalled to Russia in 1811 and briefly dismissed from the service, in 1812 he was appointed ambassador to Sardinia in Turin, where he remained until 1816. During the brief peace between France and Russia after the signing of the Treaties of Tilsit in 1807, Kozlovsky helped a group of French officers escape English captivity, for which he was awarded the Cross of the Légion d'honneur by the Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte. He was closely involved in the negotiations on the demarcation of the frontiers between Switzerland, France, and the Kingdom of Sardinia and was also a minor member of the Russian delegation to the Congress of Vienna (1814–1815).

Kozlowski was familiar with François-René de Chateaubriand and Hugues Felicité Robert de Lamennais, under whose influence secretly converted to Catholicism from Russian Orthodoxy, his religion by birth. In 1816 he married an Italian called Giovanetta Rebora.

In 1818, he was appointed ambassador simultaneously to the Kingdom of Württemberg in Stuttgart and the Grand Duchy of Baden in Karlsruhe, but in 1820 a political dispute with the Russian government, caused by his public defence of the beginnings of democratic government in these states, led to his resignation and self-imposed exile, although he continued to receive a salary and remain, theoretically at least, available for service. During this period he turns up for varying lengths of time in Austria (1821–1822, in Vienna, Graz, Prague, Teplitz), Switzerland, France (1823–1824 in Paris), Germany (1825-6, in Berlin), the Netherlands and London (from 1829).

Even after the new government of Tsar Nicholas I almost halved his salary in 1827, Kozlovsky remained interested in political events, hoping for active employment during the Russo-Turkish war of 1828–1829, a post as Russian Consul in Hamburg in 1830, and watching the events of the July Revolution of 1830 in France and the Belgian Revolution of the same year. Events in France prompted him to write his Lettres au duc de Broglie sur les prisonniers de Vincennes, in which he pleaded the innocence of former ministers under Charles X. The Belgian revolution prompted him to write Belgium in 1830 in the hope of influencing British policy. The work was not published, however, until 1831, by which time it had been overtaken by events.

Kozlovsky only returned to Russia in 1835, having suffered a serious injury in an accident in Poland which left him permanently disabled. In the summer of 1836 he finally returned to diplomatic life as a member of Paskevich's Council for the Kingdom of Poland in Warsaw, so that during the last four years of his life he was travelling between Warsaw and St. Petersburg. He died in Baden-Baden where he had gone to take the waters for health reasons.

During the 1810s in Italy Kozlovsky married Giovanetta Rebora from Milan who bore him a son Charles, and in 1817 a daughter, Sophie (Sofka) Koslowska (died in 1878). Sophie was in close contact with the French novelist Honoré de Balzac, who followed Kozlovsky as the lover of Frances Sarah Lovell (1804–1883), wife of Count Emilio Guidoboni-Visconti. One sister, Maria Borisovna (1788–1851), a poet in her own right, was the mother of the composer Alexander Sergeyevich Dargomyzhsky (Александр Сергеевич Даргомыжский), another, Daria Borisovna, was married to the poet, translator and state councillor Michail Sergeyevich Kaisarov (1780–1825, Михаил Сергеевич Кайсаров)

Literary life

Even before his exile Kozlovsky had become a well-known figure in polite society and literary circles in Western Europe. In Rome he had met and become a friend of François-René de Chateaubriand and met Madame de Staël, with whom he continued to correspond after his move to Cagliari. Here he met the future King of France, Louis-Philippe, with whom he is reputed to have discussed Shakespeare on long sea-side walks. While in Cagliari, Kozlovsky also met the Scottish writer John Galt. Galt dedicated his Letters from the Levant to him and also provided him with introductions to Byron and Sir Walter Scott when Kozlovsky passed through London on his way to Turin. On 30 June 1813 he received an honorary Doctorate of Civil Law from the University of Oxford.

.jpg.webp)

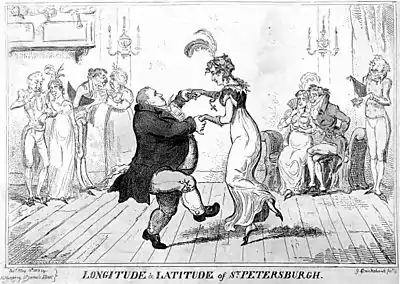

Kozlovsky first appears in London in early 1812, and seems to have made an immediate impression on English society. In a letter to Lady Morpeth in February 1812, Harriet Countess Granville wrote "London swarms with Russians. A fat nephew of the Princess Galitzin, a Prince something, Koslouski I believe, was going to Sardinia, but he has fallen so desperately in love with a beautiful girl, Mrs Tom Sheridan's youngest sister, that he scarcely can ...". The novelist Maria Edgeworth wrote of him in a letter to her sister: "I know nothing of him but that he is short and fat and looks good-humoured and like two men bound in one. He says he has a great desire to pay me his homage. If he throws himself at my feet he will never be able to get up again." Kozlovsky's prodigious obesity was captured in the caricature by George Cruikshank Longitude and Latitude of St. Petersburgh. A further aspect of Kozlovski's reputation was summed up in an anonymous caricature entitled L'aimable roué, published in 1813. Kozlovsky appears to have visited Byron on a number of occasions complaining of the English husband and the restrictions upon their wives, but Byron's plan to return to the Mediterranean with him in the summer of 1813 came to nothing. In subsequent years Kozlovsky had friendly relations with the British King George IV. The Times records on 15 June 1829 that he had been presented to the King at a ball and a year later (The Times, 2 June 1830) he was in London again inquiring after health of the ailing King.

During his period as ambassador in Baden, Kozlovsky had become a friend of Karl August Varnhagen von Ense, the German writer who was briefly Prussian ambassador in Karlsruhe, and during his 'exile' Kozlovsky became a constant companion of the poet Heinrich Heine during his stay in August 1826 on the island of Norderney.

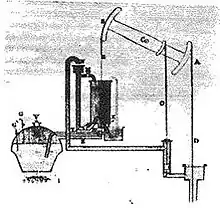

Back in Russia, Kozlovsky became part of the literary circles including Vasily Zhukovsky, Pyotr Vyazemsky, and Alexander Pushkin. In 1836 and 1837, he contributed three popular scientific articles to Pushkin's journal Современник (The Contemporary). The first, in part 1, was Разборъ парижского математическаго ежегодника на 1836 годъ, a review of the Annuaire du Bureau des Longitudes for 1836 edited by François Arago; the second, in part 3, was О надежде (On Hope), an article on probability theory; the third, in part 6, was Краткое начертание теории паровых машин, (A short outline of the theory of steam engines), which was illustrated.

Note on transliteration

Kozlovsky's name appears in numerous forms, depending on the language it is transliterated into: Kozlovski/y, Koslowski/y, Koslofski/y, Koslouski/y, etc. According to Wilhelm Dorow, the Prince himself seems to have preferred Kosloffsky, one of the less common forms.

References

- Honoré de Balzac: Correspondance, tom. IV (1840–1845), ed. Roger Pierrot, Paris 1966, p. 831

- Petr Dolgorukov: Rossiyskaya Rodoslovnaya Kniga («Россійская Родословная Книга»), St. Petersburg 1854

- Wilhelm Dorow: "Der russische Fürst Kosloffsky und seine nachgelassenen Denkwürdigkeiten", Krieg, Literatur und Theater. Mittheilungen zur neueren Geschichte, Leipzig 1845, 1-24

- Wilhelm Dorow: Fürst Kosloffsky, Leipzig 1846

- Maria Edgeworth, Letters from England, Oxford 1971, letter dated 18.5.1813.

- В.Я. Френкель, "Ценитель умственный творений исполинских" Формулы на страницах "Современника"

- Ian A Gordon, John Galt: the Life of a Writer, Edinburgh 1972

- F. Leveson Gower: Letters of Harriet Countess Granville 1810–1845, vol I, London 1894

- Heinrich Heine, Briefe, ed. Friedrich Hirth, vol. I, Mainz 1950

- Leslie A. Marchand (ed.), Byron's Letters and Journals. vol. III: Alas! the love of women! London 1973

- Аркадий Мурашев: "Друг бардов английских..." ("сурсики" о князе Козловском), Moscow 2006.

- A. A. Polowzow: Russki Biografitscheski Slowar («Русскій Біографическій Словарь»), St. Petersburg 1903

- Gleb Struve: "Un Russe européen: Le prince Pierre Kozlovski", Revue de Littérature Comparée 24 (1950) 521-546

- Gleb Struve: Who was Pushkin's "Polonophil"?, Slavonic and East European Review 29 (1950/51) 444-455

- "Kozlowski PB" / / The Catholic Encyclopedia . M. 2005. Volume 2 of Art. 1144-1145

Works

- Verses to Prince Kurakin («Стихи князю Куракину»), St. Petersburg 1802; re-published in П. А. Дружинин, Неизвестные письма русских писателей князю Александру Борисовичу Куракину (1752–1818), Москва 2002 (P. A. Druzhinin, Unknown Letters of Russian Writers to Prince Alexander Borisovich Kurakin (1752–1818) Moscow 2002)

- Russian translation of Goethe's Die Leiden des jungen Werther (unpublished)

- History of Genoese Power in the Crimea («История господства генуэзцев в Крыму»), unpublished

- Tableau de la cour de France, 1824

- Lettre d'un protestant d'Allemagne à Monseigneur l'évêque de Chester, sur le discours prononcé par Sa Grandeur le 17 mai, dans la Chambre des Pairs [sur les catholiques irlandais], Paris 1825

- Lettres au duc de Broglie sur les prisonniers de Vincennes, Ghent 1830

- Belgium in 1830, London 1831

- "Разборъ парижского математическаго ежегодника на 1836 годъ", Современник, part 1, 1836

- "О надежде", Современник part 3, 1836

- "Краткое начертание теории паровых машин", Современник, part 6, 1837

- Diorama social de Paris: par un étranger qui y a séjourné l'hiver de l'année 1823 et une partie de l'année 1824 (new edition by Véra Miltchina and Alexandre Ospovate), Paris 1997