| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Pyribenzamine |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Multum Consumer Information |

| MedlinePlus | a601044 |

| Routes of administration | Oral, intravenous |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Metabolism | Hepatic hydroxylation and glucuronidation |

| Elimination half-life | 4–6 hours[1] |

| Excretion | Renal |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number |

|

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.001.910 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

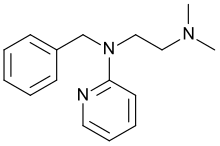

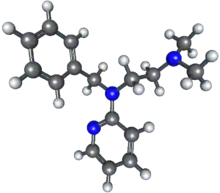

| Formula | C16H21N3 |

| Molar mass | 255.365 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Tripelennamine, sold under the brand name Pyribenzamine by Novartis, is a drug that is used as an antipruritic and first-generation antihistamine. It can be used in the treatment of asthma, hay fever, rhinitis, and urticaria, but is now less common as it has been replaced by newer antihistamines. The drug was patented at CIBA, which merged with Geigy into Ciba-Geigy, and eventually becoming Novartis.

Medical uses

Where and when it is/was in common use, tripelennamine is used much like other mildly-anticholinergic antihistamines to treat conditions of the upper respiratory tract arising from illnesses and hay fever. It can be used alone or in combination with other agents to have the desired effect. Cough medicines of the general formula tripelennamine + codeine/dihydrocodine/hydrocodone ± expectorant ± decongestant(s) are popular where available. Among these are the Pyribenzamine cough syrups which contain codeine, with and without decongestants, listed in the 1978 Physicians' Desk Reference; the codeine-tripelennamine synergy is well-known and makes such mixtures more useful for their intended purposes.

Side effects

Tripelennamine is mildly sedating. Other side effects can include irritation, dry mouth, nausea, and dizziness.

A large study on people 65 years old or older linked the development of Alzheimer's disease and other forms of dementia to the "higher cumulative" use of first-generation antihistamines, due to their anticholinergic properties.[2]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

Tripelennamine acts primarily as an antihistamine, or H1 receptor antagonist. It has little to no anticholinergic activity, with 180-fold selectivity for the H1 receptor over the muscarinic acetylcholine receptors (for comparison, diphenhydramine had 20-fold selectivity for the H1 receptor).[3] In addition to its antihistamine properties, tripelennamine also acts as a weak serotonin-norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitor (SNDRI).[4][5][6]

Pharmacokinetics

The elimination half-life of tripelennamine is 4 to 6 hours.[1] In a clinical study, the half-life of tripelennamine following intramuscular injection of 50 to 100 mg was 2.9 to 4.4 hours.[7][8]

History

Tripelennamine was patented in 1946 by Carl Djerassi and colleagues, working at CIBA in New Jersey.[9]

Society and culture

Availability

Tripelennamine is no longer available in the United States.[10]

See also

References

- 1 2 Goldfrank LR, Flomenbaum N (2006). Goldfrank's toxicologic emergencies. McGraw-Hill Professional. p. 787. ISBN 978-0-07-147914-1. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- ↑ Gray SL, Anderson ML, Dublin S, Hanlon JT, Hubbard R, Walker R, et al. (March 2015). "Cumulative use of strong anticholinergics and incident dementia: a prospective cohort study". JAMA Internal Medicine. 175 (3): 401–407. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.7663. PMC 4358759. PMID 25621434.

- ↑ Kubo N, Shirakawa O, Kuno T, Tanaka C (March 1987). "Antimuscarinic effects of antihistamines: quantitative evaluation by receptor-binding assay". Jpn J Pharmacol. 43 (3): 277–82. doi:10.1254/jjp.43.277. PMID 2884340.

- ↑ Oishi R, Shishido S, Yamori M, Saeki K (February 1994). "Comparison of the effects of eleven histamine H1-receptor antagonists on monoamine turnover in the mouse brain". Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology. 349 (2): 140–4. doi:10.1007/bf00169830. PMID 7513381. S2CID 20653998.

- ↑ Sato T, Suemaru K, Matsunaga K, Hamaoka S, Gomita Y, Oishi R (May 1996). "Potentiation of L-dopa-induced behavioral excitement by histamine H1-receptor antagonists in mice". Japanese Journal of Pharmacology. 71 (1): 81–4. doi:10.1254/jjp.71.81. PMID 8791174.

- ↑ Yeh SY, Dersch C, Rothman R, Cadet JL (September 1999). "Effects of antihistamines on 3, 4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine-induced depletion of serotonin in rats". Synapse. 33 (3): 207–17. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(19990901)33:3<207::AID-SYN5>3.0.CO;2-8. PMID 10420168. S2CID 16399789.

- ↑ Yeh SY, Todd GD, Johnson RE, Gorodetzky CW, Lange WR (June 1986). "The pharmacokinetics of pentazocine and tripelennamine". Clin Pharmacol Ther. 39 (6): 669–76. doi:10.1038/clpt.1986.117. PMID 3709032. S2CID 22682721.

- ↑ Sharma A, Hamelin BA (April 2003). "Classic histamine H1 receptor antagonists: a critical review of their metabolic and pharmacokinetic fate from a bird's eye view". Curr Drug Metab. 4 (2): 105–29. doi:10.2174/1389200033489523. PMID 12678691.

- ↑ Landau R, Achilladelis B, Scriabine A (1999). Pharmaceutical Innovation: Revolutionizing Human Health. Chemical Heritage Foundation. ISBN 978-0-941901-21-5.

- ↑ "Drugs@FDA: FDA-Approved Drugs".