| Winged mapleleaf | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Mollusca |

| Class: | Bivalvia |

| Order: | Unionida |

| Family: | Unionidae |

| Genus: | Quadrula |

| Species: | Q. fragosa |

| Binomial name | |

| Quadrula fragosa (Conrad, 1836) | |

| Synonyms[4] | |

| |

The winged mapleleaf, also known as false mapleleaf, or hickory nut shell, and with the scientific name Quadrula fragosa, is a species of freshwater mussel. It is an aquatic bivalve mollusk in the family Unionidae, the river mussels. It is endemic to the United States.

Quadrula fragosa is only located in a few parts of Wisconsin, Minnesota, Arkansas, and Missouri — in the Midwestern United States. It is a federal critically endangered river mussel species.[2]

Description

The anterior end of the Quadrula fragosa shell is slightly rounded and the posterior end of the shell is more of a square shape.

The shell can range in color from a yellowish-green to light or dark brown. The inside of the shell is white, and there is sometimes iridescent coloring at one end of the shell. The diameter of a mature mussel of this species is usually about 4 inches (10.2 cm).

The shells of these mussels are very thick, and unlike many other mussels, there are bumps on the shell surface running down from the hinge of the shell to the outside edges. It is the patterns of these bumps that help to distinguish the winged mapleleaf from many other mussels that look very similar in appearance.

Habitat

The winged mapleleaf is found in medium to large streams and rivers. it can sometimes be found in the mud, but it is more commonly either found in gravel or sandy bottoms. The mussel does need to be in moving water in order to survive, the depth of this running water also needs to be somewhere between 0.4 and 2.0 meters. The water must be free of pollutants and clean.

Range

At one time the winged mapleleaf could be found in thirteen states. It lived in nearly all the rivers and streams that flow into the Mississippi River. It was once also found in some rivers and streams that flow into the Missouri River.

Today however, the mussel can only be found in four or five river systems in the Midwestern United States, and only found in limited areas of those rivers: in a five-mile stretch of the St. Croix River, which flows between the states of Minnesota and Wisconsin; In Arkansas it can be found in the Ouachita River and also the Saline River; some populations have been located in the Bourbeuse River in Missouri as well as the Little River in Oklahoma.[5][6] Of these locations, the population of these mussels in the St. Croix River is the only one that has been proven to actually be persistent.[5] Winged mapleleaf mussels in the Ouachita and Saline Rivers may have a viable population.[5] It is currently estimated that there are somewhere between 10,000 and 100,000 surviving individuals rangewide.[5]

Feeding

The mussel filters out tiny food particles, either phytoplankton or zooplankton. The young winged mapleleafs attach themselves to the gills of a host fish for feeding and growing purposes until they reach the stage in their life cycle that they can themselves siphon in the water from the river of the stream that they are in.

Reproduction

.jpg.webp)

Reproduction of the winged mapleleaf is very similar to that of many other freshwater mussels. The males release their sperm into the water, then as the females siphon in water the sperm fertilizes the eggs which are located on their gills. After fertilization the eggs develop into a larva, and once the larva reaches a certain stage it is released from the gills of the mother mussel into the river current. The larva then must reach the gills of a host fish where it can then continue its growing process. The only currently known host fish are the channel catfish and the blue catfish.[5]

The larva continue growing on the host fish until they reach their next life cycle stage, and once this stage is reached they are released from the gills of the host fish and find their way to the bottom of the river or stream. Once they have reached the bottom, they then begin maturing into the adult stage of their life cycle. The actual reason for the channel catfish and the blue catfish being the only host fish to successfully have a larva mature on them is still unknown.

Research was even done by a group of researchers where they used divers to see if they could plant the larva from the mother onto the gills of fish other than the two kinds of catfish. The research was limited from a number of different causes, a limited number of eggs found in the area to transplant on to captive fish, and also the deal of many of the fish that they had captive. The results, however they were very limited, still only showed the Channel and the Blue catfish to be successful host fish for the winged mapleleaf. The oldest known organism in this species is in the St. Croix River and is estimated to be 22 years old, although, the life span of the mussel is actually unknown.

Threats

The winged mapleleaf currently faces a number of different threats to its survival. The invasion of the Zebra mussel Dreissena polymorpha, (which the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service trying to control) is one of the biggest threats to the survival of the winged mapleleaf. The Zebra mussel is an extremely invasive species and in 2000 the Zebra mussel began being a problem in the St. Croix River. Sediment accumulation and loss of water quality are also major threats to the population of the mussel.

The reproducing population in the St. Croix River area is near the metropolitan area of St. Paul, and as the larger cities begin to become further developed, sediment is dispersed into the river and more and more pollution occurs. This can also change the flow of the river, causing erosion and a change in water levels. The winged mapleleaf needs to be in a clean environment and can only survive in certain water levels.

Upstream dam operations also cause changes in the water level, which is another issue that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is trying to take action towards. The biggest issue that the mussel currently faces right now is that there is only one known reproducing population. This means that a severe rainstorm that caused flooding, a pollution spill, or the outbreak of an upstream dam could easily wipe out the entire population and cause this mussel species to become extinct.

Extinction preventions

.jpg.webp)

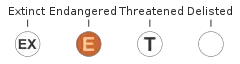

The winged mapleleaf was added to the list of endangered and threatened plants and animals effective July 22, 1991.[3] It is now illegal to collect, harm, threaten, or kill the mussel. Permits can be issued from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to give individuals rights to collect some individuals to conduct research projects, but these permits are not easily attained. The State of Wisconsin and the state of Minnesota are working with the help of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to try to control the invasion of the Zebra mussel.

There is also currently an experimental population of the winged mapleleaf that has been released into the wild. This experimental population was released in parts of the Tennessee River in Colbert and Lauderdale counties.[7][8] Whether or not these released populations are reproducing, has yet to be proven.

Many of the upstream dam operations have also begun to be more closely monitored in order to ensure that there is an adequate flow of water in the St. Croix River for the winged mapleleaf to survive and reproduce. The levels of the river are being kept between the constant 0.4 and 2.0 meters that the mussel needs in order to survive.

References

- ↑ Bogan, A.E.; Seddon, M.B.; et al. (Mollusc Specialist Group) (1996). "Quadrula fragosa". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 1996: e.T19040A8792671. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.1996.RLTS.T19040A8792671.en. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- 1 2 "Winged Mapleleaf (Quadrula fragosa)". Environmental Conservation Online System. U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. Retrieved 24 September 2023.

- 1 2 56 FR 28345

- ↑ "Quadrula fragosa (Conrad, 1836)". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 25 September 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 NatureServe (1 September 2023). "Quadrula fragosa". NatureServe Network Biodiversity Location Data accessed through NatureServe Explorer. Arlington, Virginia: NatureServe. Retrieved 27 September 2023.

- ↑ Galbraith, Heather S.; Spooner, Daniel E.; Vaughn, Caryn C. (2008). "Status of Rare and Endangered Freshwater Mussels in Southeastern Oklahoma". The Southwestern Naturalist. 53 (1): 45–50. doi:10.1894/0038-4909(2008)53[45:SORAEF]2.0.CO;2. JSTOR 20424891. S2CID 35508608.

- ↑ 66 FR 32250

- ↑ 66 FR 43808

Sources

- Bauer, Gerhard. Ecology and Evolution of the Freshwater Mussels. 2001. Springer Publishing

- Steingraber, Mark. U.S. fish and wildlife Service. Fort Snelling, MN http://www.fws.gov/midwest/LaCrosseFisheries/projects/mapleleaf.html

- Endangered species facts [electronic resource] : winged mapleleaf Electronic books

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. [Washington, D.C.] : U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, [2004] Online Access

- Endangered species facts [electronic resource] Electronic books

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. [Washington, D.C.] : U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, [2001] Online Access

- Host fish identification and early life thermal requirements for the federal endangered winged mapleleaf mussel [electronic resource] Electronic books

Upper Midwest Environmental Sciences Center (Geological Survey). La Crosse, Wis. : U.S. Dept. of the Interior, U.S. Geological Survey, Upper Midwest Environmental Sciences Center, [2005] Online Access

- Hornback, Daneil; March, James; Deneka, Tony; Troelstrup, Nels; Perry, James. "Factors Influencing the Distribution and Abundance of the Endangered Winged Mapleleaf Mussel Quadrula fragos in the St. Croix River, Minnesota and Wisconsin." American Midland Naturalist Volume 136.October, 1996 278-286. Accessed April 15, 2008

- Bleam, Daniel, Cope, Charles; Couch, Karen; Distler, Donald. "The Winged Mapleleaf, Quadrula fragosa in Kansas." Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science Volume 101(1998) 35-38. April 17, 2008

- Steingraeber, Mark, Bartsch, Michelle; Kalas, John; Newton, Teresa. "Thermal Criteria for Early Life Stage Development of the Winged Mapleleaf Mussel (Quadrula fragosa).." American Midland Naturalist 157(2006) 297-311. April 17, 2008