Sir George Hayter's coronation portrait of the Queen | |

| Date | 28 June 1838 |

|---|---|

| Location | Westminster Abbey, London, England |

| Budget | £70,000 |

| Participants |

|

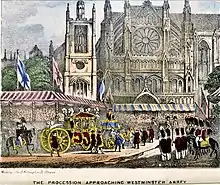

The coronation of Victoria as Queen of the United Kingdom took place on Thursday, 28 June 1838, just over a year after she succeeded to the throne of the United Kingdom at the age of 18. The ceremony was held in Westminster Abbey after a public procession through the streets from Buckingham Palace, to which the Queen returned later as part of a second procession.

Planning for the coronation, led by the prime minister, Lord Melbourne, began at Cabinet level in March 1838. In the face of various objections from numerous parties, the Cabinet announced on Saturday, 7 April, that the coronation would be at the end of the parliamentary session in June. It was budgeted at £70,000, which was more than double the cost of the "cut-price" 1831 coronation, but considerably less than the £240,000 spent when George IV was crowned in July 1821. A key element of the plan was presentation of the event to a wider public.

By 1838, the newly built railways were able to deliver huge numbers of people into London and it has been estimated that some 400,000 visitors arrived to swell the crowds who thronged the streets while the two processions took place and filled the parks where catering and entertainment were provided. Hyde Park was the scene of a huge fair, including a balloon ascent. The fair was scheduled to take place over two days, but was in the end extended by popular demand to four days. Green Park featured a firework display the night after the ceremony. The coronation coincided with a period of fine weather and the whole event was generally considered a great success by both the press and the wider public, although those inside the Abbey witnessed a good deal of mishap and confusion, largely due to lack of rehearsal time. In the country at large, there was opposition to the coronation by Radicals, especially in the North of England.

Background and planning

Queen Victoria succeeded her uncle King William IV on 20 June 1837.[1] Her first prime minister was Lord Melbourne, with whom she developed a close personal friendship.[2] Until 1867, the Demise of the Crown automatically triggered the dissolution of parliament: voting in the subsequent general election took place between 24 July and 18 August. The result was a victory for Melbourne, whose Whig Party government was returned to power for another four years. Their majority over the opposition Conservative (formerly Tory) Party was reduced from 112 seats to 30. Melbourne was the leading player in the planning, preparation and implementation of Victoria's coronation.[3]

Melbourne's Cabinet began formal discussions of the subject of the coronation during March 1838.[4] A major factor in the planning was that the coronation was the first to be held since the Reform Act of 1832, when the government radically reshaped the monarchy.[3] In terms of the ceremony itself, the extension of the franchise meant that some 500 members of Parliament would be invited to attend, in addition to the peerage.[5] A greater consideration was the need to somehow involve the general public, and Melbourne championed the centuries-old custom of a public procession taking place through the streets of London.[3] There had been a procession in 1831, but a much longer route was planned for 1838, that included a new startpoint at Buckingham Palace. Earlier processions had run from the Tower of London to the Abbey. Victoria's procession would be the longest since that of Charles II in April 1661.[6] Scaffolding for spectators would be built all along the route.[3] According to contemporary reports, this was achieved, with one report stating that there was scarcely "...a vacant spot along the whole [route]... ...that was unoccupied with galleries or scaffolding".[7] The diarist Charles Greville commented that the principal object of the government plan was to amuse and interest the ordinary working people.[3] He later concluded that the "great merit" of the coronation was that so much had been done for the people.[6]

In terms of the cost, the government was torn between the extremes of George IV's lavish coronation in 1821 and the "cut-price" event, dubbed the "Half-Crown-ation", that had been held for William IV in 1831. It decided to allow a budget of £70,000,[4] which represented a compromise between two extremes of £240,000 (1821) and £30,000 (1831).[3]

Objections

The government's plans for the coronation attracted considerable criticism from its opponents. For different reasons, both the Tories and the Radicals objected to the coronation being turned into a day of popular celebration, to be seen by as wide a public as possible. The Tory objections, mostly made beforehand, were that the government's plans to put much of the spending into the long public procession detracted from the traditional dignity of the ceremonies at Westminster, which would be "shorn of majesty by Benthamite utilitarianism".[8] The Radical left, including the Chartist movement which was largely anti-monarchist, thought the whole occasion far too expensive.[9]

A dubious perception that prevailed was the identification of the new monarch with the Whig party. This would be a problem through the early years of Victoria's reign, leading to the so-called Bedchamber Crisis in 1839 over what were at the time considered to be the political nature of the appointments of her ladies-in-waiting. In addition, the Whig party exploited Victoria's name in its election campaign, suggesting that a monarch from a new generation would inevitably mean the progress of reform. William IV and his wife Adelaide of Saxe-Meiningen had strong Tory sympathies, whilst Victoria's mother and namesake was known to favour the Whigs. It was assumed—to some extent correctly—that Victoria herself had been brought up to hold similar views. This was reflected in popular ballads sold on the streets, one of which had Victoria saying:[10]

I'll make some alterations,

I'll gain the people's right,

I will have a radical Parliament

Or they don't lodge here tonight.

The government's decision to dispense with certain traditions, including the exclusive banquet at Westminster Hall and medieval rituals such as having a monarchical champion throwing down a gauntlet, was seen by the Tory aristocracy as a snub.[3] In the House of Lords, complaints were made about the procession of a young girl in public (Victoria was nineteen), that would cause her to be "exposed to the gaze of the populace".[3] On a commercial footing, an association of London traders objected to the planned date, stating that they needed more time to order their merchandise. They favoured a date in August.[4]

There were generic objections to the coronation, which were based on an underlying opposition to the monarchy as an institution.[11] The historian Lucy Worsley believes that had it not been for Victoria's popularity as a young woman, in contrast with her uncles, especially the despised George IV, the monarchy would have been "an institution in danger".[11] There was a view that, within an age of reform, the coronation would be a medieval anachronism.[11]

The Tory campaign of protest included several public meetings, and an open letter from the Marquess of Londonderry to the Lord Mayor of London and the aldermen and tradesmen, published in The Times on Saturday, 2 June. The campaign culminated with Londonderry's speech in the House of Lords on a motion, when he asked the Queen to postpone the coronation until 1 August so that it could be carried out with "proper splendour".[12]

The Radical left, whose press complained of the expense during the run-up to the day, concentrated on trying to dampen public enthusiasm. They had some success in the north of England. In Manchester, a campaign organised by trade unions and other groups reduced the attendance at the local procession organised by the city council to a third of the turnout of that for the previous coronation.[3][13] In several manufacturing towns of northern England, the Chartists co-ordinated anti-monarchist demonstrations.[9]

Public procession and crowds

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

Prior to 1838, only the peerage had taken part in a coronation. The day's ceremonies would have begun in Westminster Hall, (now attached to the Houses of Parliament), and upon their completion, peers would have walked together across the road to Westminster Abbey, where they witnessed the monarch being crowned.[8] In accordance with Melbourne's new plan, however, the traditional ceremonies in Westminster Hall and the procession to the Abbey were replaced with two much longer processions through London. Victoria travelled inside the Gold State Coach (also known as the Coronation Coach), made for George III in 1762, as part of a procession which included many other coaches, and a cavalry escort.[3][14] According to The Gentleman's Magazine it was the longest coronation procession since that of Charles II in 1660.[3][14][15] A large proportion of the budget was used to pay for the procession and so there was no coronation banquet.[3]

The route was designed to allow as many spectators as possible to view the procession. It followed a roughly circular route from the newly completed Buckingham Palace, past Hyde Park Corner and along Piccadilly, St James's Street, Pall Mall, Charing Cross and Whitehall, to Westminster Abbey: the journey took a whole hour.[16] The processions to and from Westminster Abbey were watched by unprecedentedly large crowds, many of the people having travelled on the new railways to London from around the country: it was estimated that 400,000 people had arrived in the capital in the days running up to the event.[3][14]

William IV's coronation established much of the pageantry of subsequent coronations.[3] The procession by coach to and from the Abbey, which first occurred in 1838, has been repeated in all subsequent coronations.[3]

Ceremony in Westminster Abbey

A "botched" coronation

The presiding cleric of the ceremony was the Archbishop of Canterbury, William Howley.

According to the historian Roy Strong, "the ceremony of 1838 was the last of the botched coronations". After the coronation, historians explored the ancient liturgical texts and put together a structured programme. They rediscovered the rites that had taken place during medieval coronations, and which were then used for the coronation of Edward VII in 1902.[3] The picturesque ritual of the Queen's Champion riding through Westminster Hall in full armour and issuing his challenge was omitted, and has never been revived; the Champion, Henry Dymoke, was made a baronet instead.[15]

There was very little rehearsal, with the result that on the day the ceremonial was marred by mistakes and accidents.[17] The Queen, who was persuaded by Lord Melbourne to visit the Abbey the evening before, afterwards insisted that as a result she then knew where to move to during the coronation service.[3] Roy Strong doubts whether she did know, and quotes Greville's comment that "the different actors in the ceremonial were very imperfect in their parts and had neglected to rehearse them".[3] In the words of Benjamin Disraeli, then a young MP, those involved "were always in doubt as to what came next, and you saw the want of rehearsal".[3][18]

The whole service lasted five hours, and involved two changes of dress for the Queen. At points in the service when they were not needed to be present at the Coronation Theatre (composed of the pavement fronting the main altar and the crossing), the royal party were able to retreat to "St. Edward's Chapel, as it is called; but which as Ld Melbourne said, was more unlike a Chapel, than anything he had ever seen, for what was called an altar, was covered with plates of sandwiches, bottles of wine, &c".[3][14][19]

The social theory writer Harriet Martineau, who had been invited to the coronation by the Queen herself, recorded a sceptical view of the day.[3][13] Martineau recorded some favourable comments, but on the whole thought that the ceremony was "highly barbaric", "worthy only of the old Pharaonic times in Egypt", and "offensive ... to the God of the nineteenth century in the Western world".[3]

Lord Rolle's accident

An accident occurred that the Queen was able to turn to her advantage, and which she later described in her journal:

"Poor old Ld Rolls [actually Lord Rolle], who is 82, & dreadfully infirm, fell, in attempting to ascend the steps, – rolled right down, but was not the least hurt. When he attempted again to ascend the steps, I advanced to the edge, in order to prevent another fall".[20]

The reaction of Charles Greville, who was present, was typical of the wider public. He noted in his account that the Queen went down a couple of steps to prevent Rolle from trying to climb them again. Greville described this as "an act of graciousness and kindness which made a great sensation".[21]

The moment was immortalised by John Martin in his large painting of the ceremony, and was also included in Richard Barham's poem "Mr. Barney Maguire's Account of the Coronation":[22]

Then the trumpets braying, and the organ playing,

And the sweet trombones, with their silver tones;

But Lord Rolle was rolling; – t'was mighty consoling

To think his Lordship did not break his bones!

.jpg.webp)

At the end of the service, the Treasurer of the Household, Lord Surrey, threw silver coronation medals to the crowd, which caused an undignified scramble.[18]

Music

As was usual, special seating galleries were erected to accommodate the guests. There was an orchestra of 80 players, a choir of 157 singers, and various military bands for the processions to and from the Abbey.[3][14] The quality of the coronation music did nothing to dispel the lacklustre impression of the ceremony. It was widely criticised in the press, as only one new piece had been written for the occasion, and the choir and orchestra were perceived to have been badly coordinated.[23]

The music was directed by Sir George Smart, who attempted to conduct the musicians and play the organ simultaneously: the result was less than effective. Smart's fanfares for the State Trumpeters were described as "a strange medley of odd combinations" by one journalist.[24] Smart had tried to improve the quality of the choir by hiring professional soloists and spent £1,500 on them (including his own fee of £300): in contrast, the budget for the much more elaborate music at the coronation of Edward VII in 1902 was £1,000.[25]

Thomas Attwood had been working on a new coronation anthem, but his death three months before the event meant that the anthem was never completed.[26] The elderly Master of the King's Musick, Franz Cramer, contributed nothing, leading The Spectator to complain that Cramer had been allowed "to proclaim to the world his inability to discharge the first, and the most grateful duty of his office – the composition of a Coronation Anthem".[27] Although William Knyvett had written an anthem, "This is the Day that the Lord hath made", there was a great reliance on the music of George Frideric Handel: no less than four of his pieces were performed, including the famous Hallelujah chorus—the only time that it has been sung at a British coronation.[28]

Not everyone was critical. The Bishop of Rochester wrote that the music "... was all that it was not in 1831. It was impressive and compelled all to realize that they were taking part in a religious service – not merely in a pageant".[23]

Queen Victoria's account

The following extracts are from Victoria's account of the events, which she wrote in her journals.

_-_Queen_Victoria_Receiving_the_Sacrament_at_her_Coronation%252C_28_June_1838_-_RCIN_406993_-_Royal_Collection.jpg.webp)

I was awoke at four o'clock by the guns in the Park, and could not get much sleep afterwards on account of the noise of the people, bands, etc., etc. Got up at seven, feeling strong and well; the Park presented a curious spectacle, crowds of people up Constitution Hill, soldiers, Bands, etc.

At ten I got into the State Coach with the Duchess of Sutherland and Lord Albemarle and we began our Progress. It was a fine day, and the crowds of people exceeded what I have ever seen; many as there were the day I went to the City, it was nothing, nothing to the multitudes, the millions of my loyal subjects, who were assembled in every spot to witness the Procession. Their good humour and excessive loyalty was beyond everything, and I really cannot say how proud I feel to be the Queen of such a Nation. I was alarmed at times for fear that the people would be crushed and squeezed on account of the tremendous rush and pressure.

I reached the Abbey amid deafening cheers at a little after half-past eleven; I first went into a robing-room quite close to the entrance where I found my eight train-bearers: Lady Caroline Lennox, Lady Adelaide Paget, Lady Mary Talbot, Lady Fanny Cowper, Lady Wilhelmina Stanhope, Lady Anne Fitzwilliam, Lady Mary Grimston and Lady Louisa Jenkinson – all dressed alike and beautifully in white satin and silver tissue with wreaths of silver corn-ears in front, and a small one of pink roses around the plait behind, and pink roses in the trimmings of the dresses.[29]

Then followed all the various things; and last (of those things) the Crown being placed on my head – which was, I must own, a most beautiful impressive moment; all the Peers and Peeresses put on their coronets at the same instant. My excellent Lord Melbourne, who stood very close to me throughout the whole ceremony, was completely overcome at this moment, and very much affected; he gave me such a kind, and I may say fatherly look. The shouts, which were very great, the drums, the trumpets, the firing of the guns, all at the same instant, rendered the spectacle most imposing. The Archbishop had (most awkwardly) put the ring on the wrong finger, and the consequence was that I had the greatest difficulty to take it off again, which I at last did with great pain. At about half-past four I re-entered my carriage, the Crown on my head, and the Sceptre and Orb in my hands, and we proceeded the same way as we came – the crowds if possible having increased. The enthusiasm, affection, and loyalty were really touching, and I shall remember this day as the Proudest of my life! I came home at a little after six, really not feeling tired. At eight we dined.[29]

Public entertainment

With the advent of railway travel into London, an estimated 400,000 visitors arrived for the event. The parks, where much of the coronation day entertainment was located, were reported as resembling military encampments.[3] The arrival of so many people, who had begun to arrive a week in advance of the coronation, brought the city to a standstill. On one occasion, Victoria's private carriage was stuck in Piccadilly for 45 minutes because of horse-drawn carts taking goods into Hyde Park for the fair.[6] Charles Greville remarked that it seemed as if the population of London had "suddenly quadrupled".[3] The main entertainment laid on was the huge fair in Hyde Park, which lasted four days. Elsewhere, there were illuminations in many places and a firework display was held in Green Park on coronation night.[3] Despite the Radical protests in some towns, much of the country used the day as an opportunity for a celebration, and events such as an al fresco meal for 15,000 on Parker's Piece in Cambridge took place.[30]

Return to the palace

In her journal for the 28th, the Queen recounted that she re-entered the State Coach at about quarter past four and proceeded back to Buckingham Palace by the same route. She described the crowds as seeming to be even greater for the return journey. She arrived home just after six, and dined at eight.[31] After dinner she watched the fireworks in Green Park "from Mama's balcony".[32] Lucy Worsley comments that this was the only time in Victoria's record of the day in which her mother appears.[33] Victoria recorded that she did not eat breakfast until 11:30 the next day and, in the afternoon, she visited the Coronation Fair in Hyde Park, commenting on how busy it was with "every kind of amusement".[34]

Victoria's coronation, following that of her uncle and predecessor, William IV, on 8 September 1831, was the last of three in the nineteenth century. At the time of her death on 22 January 1901, aged 81, she was the longest-reigning British monarch, her record being broken by Elizabeth II in September 2015. The next coronation, the first of four in the twentieth century, was that of Victoria's son and successor, Edward VII, on Saturday, 9 August 1902.

Crown jewels and coronation robes

Since the coronation of Charles II, St Edward's Crown had been used at the climax of the ceremony, but it was anticipated that its size and weight (5 lb) would be too great for Victoria to bear, and so a smaller Imperial State Crown was made for her by the Crown Jewellers Rundell, Bridge & Co., using a total of 3,093 gems.[35] These included the Black Prince's Ruby (a spinel), set on the front cross pattée; the cross at the top was set with a stone known as St Edward's Sapphire, a jewel taken from the ring (or possibly the coronet) of Edward the Confessor.[36] Victoria wore the George IV State Diadem in the returning procession.[31]

Victoria's coronation crown was badly damaged when an accident occurred at the State Opening of Parliament in 1845.[37] The stones were subsequently removed: the empty gold frame is currently on display in the Martin Tower in the Tower of London. The gems were remounted in a new and lighter crown for the coronation of George VI in 1937 by Garrard & Co. Limited.[38]

For the journey to Westminster Abbey, Victoria wore a crimson velvet robe over a stiff white satin dress with gold embroidery. The train of her robe was extremely long and was later described by her maid of honour, Wilhelmina Stanhope, as "a very ponderous appendage".[39] The Mistress of the Robes was Harriet, Duchess of Sutherland.[40] Having been proclaimed queen by the assembly in the Abbey, Victoria retired to a special robing room where she replaced the crimson cloak with a lighter white linen gown trimmed with lace.[41] Wearing this, she returned to the Abbey for the presentation to her of the Crown Jewels.[42] The Queen's coronation robes, along with her wedding dress and other items, remain in the Royal Collection and are kept at Kensington Palace. She wore the robes again in the 1859 portrait by Franz Xaver Winterhalter and on her Golden Jubilee in 1887. A marble statue showing her wearing them in 1838 was placed in Kensington Gardens near the palace.[43]

Royal guests

As reported in The London Gazette:[44]

- The Duchess of Kent and Strathearn, the Queen's mother

- The Prince of Leiningen, the Queen's half-brother

- The Princess of Hohenlohe-Langenburg, the Queen's half-sister[45]

- The Duke of Sussex, the Queen's paternal uncle

- The Duke and Duchess of Cambridge, the Queen's paternal uncle and aunt

- Prince George of Cambridge, the Queen's first cousin

- Princess Augusta of Cambridge, the Queen's first cousin

- The Princess Augusta Sophia, the Queen's paternal aunt

- The Duchess of Gloucester and Edinburgh, the Queen's paternal aunt

- The Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, the Queen's maternal uncle

- The Earl of Munster, the Queen's first cousin

Prince Christian of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg, the Queen's third cousin (representing his uncle, the King of Denmark)

Prince Christian of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg, the Queen's third cousin (representing his uncle, the King of Denmark).svg.png.webp) The Duke of Nassau, the Queen's third cousin

The Duke of Nassau, the Queen's third cousin.svg.png.webp) The Duke of Nemours (representing his father, the King of the French)

The Duke of Nemours (representing his father, the King of the French)- Prince Ernest Frederick of Hesse-Philippsthal-Barchfeld (representing his brother, the Landgrave of Hesse-Philippsthal-Barchfeld)

.svg.png.webp) The Prince of Ligne (representing the King of the Belgians)

The Prince of Ligne (representing the King of the Belgians)

Other guests

The Count Grigory Alexandrovich Stroganov (representing the Tsar of Russia)

The Count Grigory Alexandrovich Stroganov (representing the Tsar of Russia).svg.png.webp) Ahmed Fethi Pasha

Ahmed Fethi Pasha.svg.png.webp) Ibrahim Sarim Pasha (representing the Ottoman Sultan)

Ibrahim Sarim Pasha (representing the Ottoman Sultan).svg.png.webp) José Joaquim Pires de Carvalho e Albuquerque (representing the Brazilian Regency of Emperor Pedro II)[46]

José Joaquim Pires de Carvalho e Albuquerque (representing the Brazilian Regency of Emperor Pedro II)[46]

References

- ↑ Worsley 2018, p. 81.

- ↑ Worsley 2018, pp. 86–87.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 Strong, Roy. "Queen Victoria's Coronation". Queen Victoria's Journals. Royal Archives. Retrieved 8 April 2019.(subscription required)

- 1 2 3 Worsley 2018, p. 94.

- ↑ Worsley 2018, pp. 94–95.

- 1 2 3 Worsley 2018, p. 95.

- ↑ Worsley 2018, p. 96.

- 1 2 Plunkett 2003, p. 22.

- 1 2 Plunkett 2003, pp. 26–27.

- ↑ Plunkett 2003, pp. 18–21 (ballad, p. 21).

- 1 2 3 Worsley 2018, p. 104.

- ↑ Plunkett 2003, p. 24.

- 1 2 Plunkett 2003, pp. 25–30.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Rappaport 2003, p. 361.

- 1 2 Plunkett 2003, pp. 22–24.

- ↑ Worsley 2018, p. 97.

- ↑ Gosling, Lucinda (2013). Royal Coronations. Oxford: Shire. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-74781-220-3.

- 1 2 Worsley 2018, p. 102.

- ↑ "Princess Beatrice's copies". Queen Victoria's Journals. Royal Archives. 28 June 1838. p. 81. Retrieved 24 May 2013.(subscription required)

- ↑ "Princess Beatrice's copies". Queen Victoria's Journals. Royal Archives. 28 June 1838. p. 79. Retrieved 24 May 2013.(subscription required)

- ↑ Wilson, Philip Whitwell, ed. (1927). The Greville Diary, Volume II. New York: Doubleday, Page & Company. p. 30.

- ↑ Verse 10 of "Mr. Barney Maguire's Account of the Coronation" by Richard Barham.

- 1 2 Range, Matthias (2012). Music and Ceremonial at British Coronations: From James I to Elizabeth II. Cambridge University Press. p. 224. ISBN 978-1-107-02344-4.

- ↑ Cowgill & Rushton 2006, p. 123.

- ↑ Cowgill & Rushton 2006, p. 121.

- ↑ Gatens, William J. (1987). Victorian Cathedral Music in Theory and Practice. Cambridge University Press. p. 84. ISBN 0-521-26808-7.

- ↑ "Metropolitan Library of Music". The Spectator (archive). 11 August 1838. p. 13.(subscription required)

- ↑ Cowgill & Rushton 2006, p. 129.

- 1 2 Arthur Christopher Benson, ed. (1907). The Letters of Queen Victoria. Vol. 1. J. Murray. p. 148.

- ↑ "Coronation of Queen Victoria". History of the World. BBC. Retrieved 8 April 2019.

- 1 2 "Princess Beatrice's copies". Queen Victoria's Journals. Royal Archives. 28 June 1838. p. 82. Retrieved 24 May 2013.(subscription required)

- ↑ "Princess Beatrice's copies". Queen Victoria's Journals. Royal Archives. 28 June 1838. p. 85. Retrieved 11 April 2019.(subscription required)

- ↑ Worsley 2018, p. 103.

- ↑ "Princess Beatrice's copies". Queen Victoria's Journals. Royal Archives. 29 June 1838. p. 85. Retrieved 11 April 2019.(subscription required)

- ↑ Quotation from a promotional colour print issued by Rundell's of the Imperial Crown, reproduced in Hartop, Royal Goldsmiths, p. 143.

- ↑ Prof. Tennant (14 December 1861). "Queen Victoria's Crown". Scientific American. 5 (24): 375.

- ↑ "Crown Jewels factsheet" (PDF). Historic Royal Palaces Agency. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 August 2022. Retrieved 11 April 2019.

- ↑ "Heritage". Garrard & Co.. Archived from the original on 25 September 2013.

- ↑ Worsley 2018, p. 92.

- ↑ Worsley 2018, pp. 92–93.

- ↑ Worsley 2018, p. 99.

- ↑ Worsley 2018, pp. 99–100.

- ↑ "Queen Victoria Statue". The Royal Parks. Retrieved 8 April 2019.

- ↑ "No. 19632". The London Gazette. 4 July 1838.

- ↑ "Key to Mr Leslie's picture of Queen Victoria receiving the Holy Sacrament at her Coronation". National Portrait Gallery.

- ↑ Imperial Annuary

Bibliography

- Cowgill, Rachel; Rushton, Julian (2006). Europe, Empire, and Spectacle in Nineteenth-century British Music. Ashgate Publishing Limited. ISBN 0-7546-5208-4.

- Plunkett, John (2003). Queen Victoria: First Media Monarch. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-1992-5392-7.

- Rappaport, Helen (2003). Queen Victoria: a biographical companion. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 1-8510-9355-9.

- Victoria, Queen (1908). Benson, Arthur Christopher; Esher, Viscount (eds.). The Letters of Queen Victoria, Volume I. 1837–1843. Albemarle Street, London: John Murray. pp. 120–125.

- Worsley, Lucy (2018). Queen Victoria – Daughter, Wife, Mother, Widow. London: Hodder & Stoughton Ltd. ISBN 978-1-4736-5138-8.

External links

- "Westminster Abbey – Queen Victoria Coronation Music, 1838" (PDF). westminster-abbey.org. The Dean and Chapter of Westminster Abbey. Retrieved 11 April 2023.

- "Queen Victoria's Coronation". Queen Victoria Online. Globevista. 2011. Archived from the original on 1 February 2014. Retrieved 10 April 2019.

- "Coronation of her most sacred majesty Queen Victoria". The London Gazette. No. 19632. 4 July 1838. p. 1509. Retrieved 8 April 2019.

.jpg.webp)