| Queers Read This | |

|---|---|

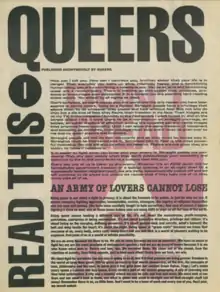

Cover page of "Queers Read This" |

"Queers Read This" (also stylized "QUEERS READ THIS!") is an essay about queer identity. The polemic was originally circulated by members of Queer Nation as a pamphlet at the June 1990 New York Gay Pride Parade. It characterizes queerness as a community based on social situation and action, in contrast to gay and lesbian identity which are considered to be based on "natural" or inherent characteristics, and suggests that to be queer is to constantly fight against oppression.

Many of the concepts initially articulated in "Queers Read This" were later elaborated on by scholars of queer theory.

Background

How can I tell you, how can I convince you, brother, sister that your life is in danger: That everyday you wake up alive, relatively happy, and a functioning human being, you are committing a rebellious act. You as an alive and functioning queer are a revolutionary.

Opening lines of "Queers Read This"[1]

The term queer was initially used as a pejorative against LGBT people. In the late 1980s, the term began to be reappropriated by activists. This reappropriation, especially popular among people of color, was associated with radical politics and rejection of liberal conservatism in the LGBT community.[2]

The period during which "Queers Read This" was written was characterized by heterosexism and homophobia, the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the United States, and frequent discriminatory violence on the basis of sexual orientation and gender expression.[1] By early April of 1990, instances of violence against LGBT people had increased 122 percent from the start of the same year, prompting the creation of direct action group Queer Nation by members of ACT UP.[3]

Publication

It is unclear who wrote "Queers Read This". The byline on the original essay reads "published anonymously by queers", and Queer Nation did not explicitly claim responsibility for the piece; it was controversial within the group as some interpreted it as advocating queer separatism or anti-heterosexual sentiment.[3] However, the essay was generally attributed to Queer Nation and understood as an explanation of the group's purpose.[3]

Members of Queer Nation first circulated "Queers Read This" in pamphlet form at the June 1990 New York Gay Pride Parade.[4] Each pamphlet was a single sheet of standard-sized newsprint, printed on both sides and folded in half to create four pages.[5] Roughly 15,000 copies of the essay were distributed by a group marching with the ACT UP contingent in the parade.[3]

Content

"Queers Read This" uses informal and accessible language. It includes many concepts on which the field of queer theory, nascent at the time the piece was written, would later elaborate. It additionally addresses the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the United States and the lack of an effective response to the epidemic at the time of writing.[4]

The essay includes multiple separate but overlapping sections with diverse voices.[1] Its tone is sometimes upbeat, sometimes negative, and sometimes angry; it consistently challenges its reader to be more visibly and actively queer.[6] Speaking to conservative and disengaged LGBT people along with politically active queers, the essay takes a consistently polemic tone in asserting that queer existence is political and revolutionary in and of itself.[1]

The essay characterizes queer identity not only as an expression of sexual orientation but also a commitment to specific action. It calls for LGBT pride and encourages the reader to "tear yourself away from your customary state of acceptance". A section focused on lesbian visibility asserts that queer women should involve themselves in revolution: "Girl, you can't wait for other dykes to make the world safe for you. Stop waiting for a better more lesbian future! The revolution could be here if we started it."[7]

An additional theme in the essay is the concept of queerness as a community accessible through choice and action, rather than a group demarcated by inherent characteristics. Queer identity is thus contrasted with gay or lesbian identity.[8]

Identity and the term queer

The essay's use of the term queer and conceptualization of queer identity alienated some potential readers when it was initially distributed; journalist Esther Kaplan noted that some parade-goers refused to take a copy of the pamphlet because it used the word. According to E. J. Rand, the effect of the title "Queers Read This" is that anyone reading the essay "must accept, no matter how momentarily or skeptically, being named as a queer".[9] The use of the term queer is justified in the essay itself as follows,[2] in a section titled "Why Queer":[10]

Ah, do we really have to use that word? It's trouble. Every gay person has his or her own take on it. For some it means strange and eccentric and kind of mysterious [...] And for others 'queer' conjures up those awful memories of adolescent suffering [...] Well, yes, 'gay' is great. It has its place. But when a lot of lesbians and gay men wake up in the morning we feel angry and disgusted, not gay. So we've chosen to call ourselves queer. Using 'queer' is a way of reminding us how we are perceived by the rest of the world.

The essay also specifically acknowledges the reappropriation of the term, stating that "QUEER can be a rough word but it is also a sly and ironic weapon we can steal from the homophobe's hands and use against him".[11]

This framing of queerness as a marginalized identity, and constitution of the reader as a member of that marginalized group, provides a basis for the text's view as to what queerness means and should mean. At one point the essay asserts that "being queer is not about a right to privacy; it is about the freedom to be public, to just be who we are. It means everyday fighting oppression; homophobia, racism, misogyny, the bigotry of religious hypocrites and our own self-hatred."[10]

Reception

Queer Nation's distribution of "Queers Read This" at the 1990 pride parade, and subsequent press coverage, established the group's public reputation. The flyer was controversial within the group itself,[3] and some people at the parade objected to its use of the term queer or refused to take a copy upon seeing the word.[9]

In a 1997 critique of queer activism, Cathy J. Cohen cited the essay[12] to support her argument that "instead of destabilizing the assumed categories and binaries of sexual identity, queer politics has served to reinforce simple dichotomies between heterosexual and everything 'queer'".[13] Cohen argued that while "in their fundamental challenge to a systemic process of domination and exclusion [...] queer activists and queer theorists are tied to and rooted in a tradition of political struggle most often identified with people of color and other marginal groups",[14] this dichotomization created a reductive understanding of oppression that lacked class consciousness and failed to account for racial oppression.[15] She also argued that the essay erred in presenting heterosexuality as the "dividing line" between oppressed and oppressor, suggesting that a focus on heteronormativity would allow "recognition that 'nonnormative' procreation patterns and family structures of people who are labeled heterosexual have also been used to regulate and exclude them".[16] Martin Joseph Ponce echoed Cohen in 2018, writing that the essay "fails to account for manifestations of queer privilege and heterosexual disadvantage constituted by class, racial, and gender asymmetries".[6]

References

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 Fawaz & Smalls 2018.

- 1 2 Alex, Finnis (March 28, 2022). "What queer means, after Ariana DeBose becomes first queer woman of colour to win an Oscar". iNews. Retrieved June 24, 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Rand 2004, p. 289.

- 1 2 Kadlec, Jeanna. "Where Does The Word "Queer" Come From?". Nylon. Retrieved June 24, 2022.

- ↑ Stryker, Susan (2004). "Queer Nation" (PDF). glbtq.com.

- 1 2 Ponce 2018, p. 315.

- ↑ Rand 2004, p. 292.

- ↑ Rand 2004, p. 293.

- 1 2 Rand 2004, p. 290.

- 1 2 Rand 2004, p. 291.

- ↑ Panfil 2020, p. 1715.

- ↑ Cohen 1997, p. 440.

- ↑ Cohen 1997, p. 438.

- ↑ Cohen 1997, p. 445.

- ↑ Cohen 1997, pp. 446–447.

- ↑ Cohen 1997, pp. 447–448.

Works cited

- Cohen, Cathy J. (May 1, 1997). "Punks, Bulldaggers, and Welfare Queens: The Radical Potential of Queer Politics?". GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies. 3 (4): 437–465. doi:10.1215/10642684-3-4-437. ISSN 1064-2684.

- Fawaz, Ramzi; Smalls, Shanté Paradigm (June 1, 2018). "Queers Read This!". GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies. 24 (2–3): 169. doi:10.1215/10642684-4324765. ISSN 1064-2684. S2CID 149905387.

- Panfil, Vanessa R. (October 14, 2020). ""Nobody Don't Really Know What That Mean": Understandings of "Queer " among Urban LGBTQ Young People of Color". Journal of Homosexuality. 67 (12): 1713–1735. doi:10.1080/00918369.2019.1613855. ISSN 0091-8369.

- Ponce, Martin Joseph (June 1, 2018). "Queers Read What Now?". GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies. 24 (2–3): 315–341. doi:10.1215/10642684-4324837. ISSN 1064-2684.

- Rand, E. J. (October 2004). "A Disunited Nation and a Legacy of Contradiction: Queer Nation's Construction of Identity". Journal of Communication Inquiry. 28 (4): 288–306. doi:10.1177/0196859904267232. ISSN 0196-8599. S2CID 145395945.

External links

- PDF scan of "Queers Read This" as originally published, via the Against Equality digital archive