In radio reception, radio noise (commonly referred to as radio static) is unwanted random radio frequency electrical signals, fluctuating voltages, always present in a radio receiver in addition to the desired radio signal. Radio noise near in frequency to the radio signal being received (in the receiver's passband) interferes with it in the receiver's circuits. Radio noise is a combination of natural electromagnetic atmospheric noise ("spherics", static) created by electrical processes in the atmosphere like lightning, manmade radio frequency interference (RFI) from other electrical devices picked up by the receiver's antenna, and thermal noise present in the receiver input circuits, caused by the random thermal motion of molecules.

The level of noise determines the maximum sensitivity and reception range of a radio receiver; if no noise were picked up with radio signals, even weak transmissions could be received at virtually any distance by making a radio receiver that was sensitive enough. With noise present, if a radio source is so weak and far away that the radio signal in the receiver has a lower amplitude than the average noise, the noise will drown out the signal. The level of noise in a communications circuit is measured by the signal-to-noise ratio (S/N), the ratio of the average amplitude of the signal voltage to the average amplitude of the noise voltage. When this ratio is below one (0 dB) the noise is greater than the signal, requiring special processing to recover the information.

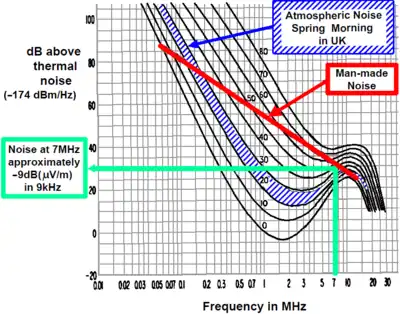

The limiting noise source in a receiver depends on the frequency range in use. At frequencies below about 40 MHz, particularly in the mediumwave and longwave bands and below, atmospheric noise and nearby radio frequency interference from electrical switches, motors, vehicle ignition circuits, computers, and other man-made sources tend to be above the thermal noise floor in the receiver's circuits.

These noises are often referred to as static. Conversely, at very high frequency and ultra high frequency and above, these sources are often lower, and thermal noise is usually the limiting factor. In the most sensitive receivers at these frequencies, radio telescopes and satellite communication antennas, thermal noise is reduced by cooling the RF front end of the receiver to cryogenic temperatures. Cosmic background noise is experienced at frequencies above about 15 MHz when highly directional antennas are pointed toward the sun or to certain other regions of the sky such as the center of the Milky Way Galaxy.

Electromagnetic noise can interfere with electronic equipment in general, causing malfunction, and in recent years standards have been laid down for the levels of electromagnetic radiation that electronic equipment is permitted to radiate. These standards are aimed at ensuring what is referred to as electromagnetic compatibility (EMC).

See also

References

- Radio noise. ITU-R Recommendation P.372, International Telecommunication Union, Geneva.

- Blackard, K.L.; et al.: Measurements and models of radio frequency impulsive noise for indoor wireless communications. IEEE Journal on Selected Areas in Communications 11 (7), September 1993.

- Dalke, R.; et al.: Measurement and analysis of man-made noise in VHF and UHF bands. Wireless Communications Conference, 1997.

- Lauber, W.R.; Bertrand, J.M.: Statistics of motor vehicle ignition noise at VHF/UHF. IEEE Trans. Electromagn. Compat. 41 (3), August 1999.

- Sanchez, M.G.; et al.: Impulsive noise measurements and characterization in a UHF digitalTV channel. IEEE Trans. Electromagn. Compat. 41 (2), May 1999.

- Blankenship, T.K.; Rappaport, T.S.: Characteristics of impulsive noise in the 450-MHz band in hospitals and clinics. IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation 46 (2), February 1998.