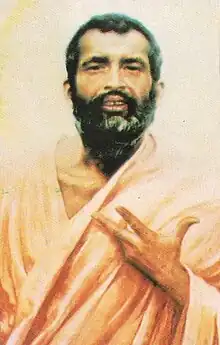

Ramakrishna (1836–1886) is a famous nineteenth-century Indian Bengali Hindu mystic. Born as he was during a social upheaval in Bengal in particular and India in general, Ramakrishna and his movement—Ramakrishna Mission played a leading role in the modern revival of Hinduism in India, and on modern Indian history.[1]

On Hinduism

Ramakrishna and his chief disciple Swami Vivekananda are regarded as two of the key figures in the Bengal Renaissance of 19th century.[2] Ramakrishna played a leading role in the modern revival of Hinduism in India and the movement—Ramakrishna Mission—his inspiration has deeply influenced modern Indian history.[3] Ramakrishna is also regarded as an influential figure on Keshab Chandra Sen and other Brahmos and on the Elite of Calcutta, the bhadralok.[4] Ramakrishna advocated bhakti[5] and the Bhagavad Gita occupies an important place in his discourses.[6] Ramakrishna preferred "the duality of adoring a Divinity beyond himself to the self-annihilating immersion of nirvikalpa samadhi", and he helped "bring to the realm of Eastern energetics and realization the daemonic celebration that the human is always between a reality it has not yet attained and a reality to which it is no longer limited".[7] He was given a name that is from the Vaishnavite tradition (Rama and Krishna are both incarnations of Vishnu), but was a devotee of Kali, the mother goddess, and known to have followed or practiced various other religious paths including Tantrism, Christianity, and Islam.[8]

Contributions

Max Müller, who was inspired by Ramakrishna, said:[9]

Sri Ramakrishna was a living illustration of the truth that Vedanta, when properly realised, can become a practical rule of life... the Vedanta philosophy is the very marrow running through all the bones of Ramakrishna’s doctrine.

Leo Tolstoy saw similarities between his and Ramakrishna's thoughts. He described him as a "remarkable sage".[10]

Romain Rolland considered Ramakrishna to be the "consummation of two thousand years of the spiritual life of three hundred million people." He said:[11]

Allowing for differences of country and of time, Ramakrishna is the younger brother of Christ.

Mohandas Gandhi wrote:[12]

Ramakrishna's life enables us to see God face to face. He was a living embodiment of godliness.

Sri Aurobindo considered Ramakrishna to be an incarnation, or Avatar, of God on par with Gautama Buddha.[13] He wrote:

When scepticism had reached its height, the time had come for spirituality to assert itself and establish the reality of the world as a manifestation of the spirit, the secret of the confusion created by the senses, the magnificent possibilities of man and the ineffable beatitude of God. This is the work whose consummation Sri Ramakrishna came to begin and all the development of the previous two thousand years and more since Buddha appeared has been a preparation for the harmonisation of spiritual teaching and experience by the Avatar of Dakshineshwar.

Jawaharlal Nehru described Ramakrishna as "one of the great rishis of India, who had come to draw our attention to the higher things of life and of the spirit."[14] Subhas Chandra Bose was also influenced by Ramakrishna. He said:[15]

The effectiveness of Ramakrishna's appeal lay in the fact that he had practised what he preached and that... he had reached the acme of spiritual progress.

Philosopher Arindam Chakrabarti called Ramakrishna "The practically illiterate, faith-bound, emotional, otherworldly esoteric Ramakrishna who prayed to the Goddess: "May my rationalizing intellect be struck by thunder!" And yet in his views about the nature of ultimate reality, the relation between the self and the body, ways of knowing truth, moral and social duties of human beings and metatheoretical explanations of why mystics disagree...Ramakrishna was no less a philosopher than Buddha or Socrates."[16]

On Indian nationalism

Rabindranath Tagore, Aurobindo Ghosh, Mahatma Gandhi, have acknowledged Ramakrishna and Vivekananda's contribution to Indian Nationalism.[17] This is particularly evident in Ramakrishna’s development of the Mother-symbolism and its eventual role in defining the incipient Indian nationalism.[18]

Vivekananda, Ramakrishna Math and the Ramakrishna Mission

Vivekananda, Ramakrishna’s most illustrious disciple, is considered by some to be one of his most important legacies. Vivekananda spread the message of Ramakrishna across the world. He also helped introduce Hinduism to the west. He founded two organisations based on the teachings of Ramakrishna. One was Ramakrishna Mission, which is designed to spread the word of Ramakrishna. Vivekananda also designed its emblem. Ramakrishna Math was created as a monastic order based on Ramakrishna’s teachings.[19]

The temples of Ramakrishna are called the Universal Temples.[20] The first Universal temple was built at Belur, which is the headquarters of the Ramakrishna Mission.

Works related to Ramakrishna

In 2006, composer Philip Glass wrote The Passion of Ramakrishna — a choral work as a "tribute to Ramakrishna". It premiered on 16 September 2006 at the Orange County Performing Arts Center in Costa Mesa, California, performed by Orange County’s Pacific Symphony Orchestra conducted by Carl St. Clair with the Pacific Chorale directed by John Alexander.[21] František Dvořák (1862–1927), a painter from Prague, inspired by the teachings of Ramakrishna made several paintings of Ramakrishna and Sarada Devi.[22]

Notes

- ↑ Jackson, p. 16.

- ↑ Pelinka, Anton; Renée Schell (2003). Democracy Indian Style. Transaction Publishers. pp. 40–41. ISBN 978-0-7658-0186-9.

The Bengali Renaissance had numerous facets including the spiritual (Hindu) renaissance, represented by the names of Sri Ramakrishna and Swami Vivekananda, the combination of spiritual, intellectual, and political aspects...

- ↑ Jackson, Carl T. "The Founders". Vedanta for the West. Indiana University Press. p. 16.

- ↑ Mukherjee, Jayasree, "Sri Ramakrishna’s Impact on Contemporary Indian Society". Prabuddha Bharata, May 2004 Online article

- ↑ Amiya P. Sen. Explorations in Modern Bengal c.1800-1900. p. 85.

- ↑ Amiya P. Sen. Explorations in Modern Bengal c.1800-1900. p. 200.

- ↑ Cohen, Martin (2008). "Spiritual Improvisations: Ramakrishna, Aurobindo, and the Freedom of Tradition". Religion and the Arts. BRILL. 12 (1–3): 277–293. doi:10.1163/156852908X271079.

- ↑ Flood, p. 257.

- ↑ Vedanta Society of New York Archived 16 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ World Thinkers on Ramakrishna-Vivekananda, The Ramakrishna Mission Institute of Culture, pp.15-16

- ↑ The Life of Ramakrishna, Advaita Ashrama

- ↑ Life of Sri Ramakrishna, Advaita Ashrama, Foreword

- ↑ World Thinkers on Ramakrishna-Vivekananda, The Ramakrishna Mission Institute of Culture, p.16

- ↑ World Thinkers on Ramakrishna-Vivekananda, The Ramakrishna Mission Institute of Culture, p.28

- ↑ World Thinkers on Ramakrishna-Vivekananda, The Ramakrishna Mission Institute of Culture, p.29

- ↑ Arindam Chakrabarti, "The Dark Mother Flying Kites: Sri Ramakrishna's Metaphysic of Morals" Sophia, 33 (3), 1994

- ↑ de Riencourt, Amaury, The Soul of India, (London: Jonathan Cape, 1961), p.250

- ↑ Jolly, Margaret,"Motherlands? Some Notes on Women and Nationalism in India and Africa".The Australian Journal of Anthropology, Volume: 5. Issue: 1-2,1994

- ↑ "Official website of Ramakrishna Math". Retrieved 2 September 2008.

- ↑ Bhuteshanandaji, Swami. "Why are Sri Ramakrishna Temples called "Universal Temples"?". Retrieved 17 August 2008.

- ↑ Philipglass.com Archived 21 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Chatterjee, Ramananda (1935). The Modern Review. Prabasi Press. p. 446.