Higdon | |

|---|---|

| Born | Ranulf Higden ca. 1280 West England |

| Died | March 12, 1364 n/a |

| Resting place | Chester Cathedral |

| Occupation(s) | Monk and theology scribe |

| Employer | Benedictine Abbey in Chester |

Ranulf Higden or Higdon (c. 1280 – 12 March 1364) was an English chronicler and a Benedictine monk who wrote the Polychronicon, a Late Medieval magnum opus. Higden, who resided at the monastery of St. Werburgh in Chester, [1] is believed to have been born in the West of England before taking his monastic vow at Benedictine Abbey in Chester in 1299. As a monk, he travelled throughout the North and Midlands of England, including Derbyshire, Shropshire and Lancashire.

Higden began compiling the Polychronicon during the reign of Edward III in the 14th century. The chronicle, which was a six-book series about world history written in Latin, was considered a definitive historical text for more than two centuries. Higden's remains are buried in Chester Cathedral.

Biography

Higden was the author of the Polychronicon, a long chronicle, one of several such works of universal history and theology. It was based on a plan taken from Scripture, and written for the amusement and instruction of his society. It is commonly styled Polychronicon, from the longer title Ranulphi Castrensis, cognomine Higden, Polychronicon (sive Historia Polycratica) ab initio mundi usque ad mortem regis Edwardi III in septem libros dispositum. The work is divided into seven books, in humble imitation of the seven days of Genesis, and, with exception of the first book, is a summary of general history, a compilation made with considerable style and taste. Written in Latin, it was translated into English by John of Trevisa (1387), and printed by Caxton (1480), and by others. For two centuries it was an approved work. It has been described as 'the most exhaustive universal history produced in medieval times and...the best seller of its age'. [2]

The first book consists of 60 chapters and provides a geographical survey of the world. It starts with a Prologue and a list of authors drawn upon, covers Asia, Africa and Europe and concludes with 23 chapters describing England.[3] The first letters of these 60 chapters create an acrostic: presentem cronicam conpilavit Frater Ranulphus Cestrensis monachis.[2] The following six books provide a history of the world: from Creation to Nebuchadnezzar (Book 2); to the birth of Christ (Book 3); to the arrival of the Saxons in England (Book 4); to the arrival of the Danes in England (Book 5); to the Norman Conquest (Book 6): to the conclusion in the reign of Edward III (Book 7).[3]

A Latin manuscript of 281 folios held by the Huntington Library in California ends initially in 1340 and is claimed to be a final version possibly written by Higden himself and edited by him up until about 1352. It belonged to St. Werburg's Abbey within his lifetime and was kept in the monastic library until the Abbey was dissolved in 1540.[2] The Latin text of the Polychronicon was never printed before the 19th. century apart from one section on British history from Book 1 which was published in a compilation assembled by Gale in 1691.[4] There are over 100 versions of the Latin or English versions published prior to 1800 held by libraries in the UK, Belgium, Ireland, the USA, France, Spain and the Vatican City [5]

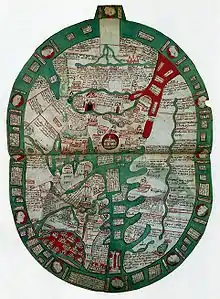

East is at the top and Jerusalem at the centre; the Red Sea at top right is coloured red.

The text has been described as a "pleasant, easy-going Universal History" but not "critical or scientific, or really historical".[6] It is plagiaristic, drawing upon many previous authorities, but this is not unusual for histories produced at the time. It seems to have enjoyed considerable popularity in the 15th century. It was the standard work on general history, and more than a hundred manuscripts of it are known to exist. The Christ Church manuscript says that Higden wrote it down to the year 1342; this document can be viewed online.[7] The fine manuscript at Christ's College, Cambridge, states that he wrote to the year 1344, after which date, with the omission of two years, John of Malvern, a monk of Worcester, carried the history on to 1357, at which date it ends.

However, according to one editor, Higden's part of the work goes no further than 1326 or 1327 at latest, after which time it was carried on by two continuators to the end.[8]

Three early translations of the Polychronicon exist. The first was made by John of Trevisa, chaplain to Lord Berkeley, in 1387, and was printed by Caxton in 1480; the second by an anonymous writer, was written between 1432 and 1450; the third, based on Trevisa's version, with the addition of an eighth book, was prepared by Caxton. These versions are specially valuable as illustrating the change of the English language during the period they cover.

The Polychronicon, with the continuations and the English versions, was edited for the Rolls Series (No. 41) by Churchill Babington (vols. i. and ii.) and Joseph Rawson Lumby (1865–1886).[3][9] This edition was adversely criticized by Mandell Creighton in the Eng. Hist. Rev. for October 1888. There is a recent translation of his sermons by Margaret Jennings and Sally A. Wilson.[10] It has been claimed that Higden was an author of the Chester Mystery Plays but this is not considered credible.[11]

Higden is buried in Chester Cathedral.

See also

Notes

- ↑ "Ranulf Higden". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 2 August 2010.

- 1 2 3 Galbraith, V.H. (1959). "An Autograph MS of Ranulph Higden's "Polychronicon"". Huntington Library Quarterly. 23 (1): 1–18. doi:10.2307/3816473. JSTOR 3816473.

- 1 2 3 C. Babington & J.R. Lumby, Polychronicon Ranulphi Higden Monachi Cestrensis together with the English Translations of John Trevisa and of an Unknown Writer of the Fifteenth Century, RS 41, 1865-68.

- ↑ Gale, Thomae (1691). Historiae Britannicae, Saxonicae, Anglo-Danicae, Scriptores XV Volume 1. Oxford. pp. 179–287.

- ↑ "Ranulf Higden". Les Archives de littérature du Moyen Âge (ARLIMA).

- ↑ Barber, E (1903). "The Discovery of Ralph Higden's Tomb". Journal of the Chester Archaeological Society. New Series. 9: 115–128. doi:10.5284/1069970.

- ↑ Christ Church MS.89 medieval.bodleian.ox.ac.uk

- ↑ Thomas Gale, in his Hist. Brit. &c., scriptores, xv. (Oxon., 1691), published that portion of it, in the original Latin, which comes down to 1066.

- ↑ "Polychronicon Ranulphi Higden, Monachi Cestrensis; together with the English translation of John Trevisa, and of an unknown Writer of the Fifteenth Century edited by Rev. Joseph Rawson Lumby, Vol. III". The Athenaeum (2282): 108–109. 22 July 1871.

- ↑ Ranulph Higden, Ars componendi sermones. Translated by Margaret Jennings and Sally A. Wilson. Introduction and Notes by Margaret Jennings (Dallas Medieval Texts and Translations 2). Louvain/Paris: Peeters, 2003. ISBN 978-90-429-1242-7.

- ↑ Bridge, Joseph (1903). "The Chester Miracle Plays: Some Facts concerning Them, and the Supposed Authorship of Ralph Higden". Journal of the Chester Archaeological Society. New Series. 9: 59–98. doi:10.5284/1069968.

References

- Lane-Poole, Reginald (1887). . In Stephen, Leslie (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 10. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 203–204.

- Taylor, John (2004). "Higden, Ranulf (d. 1364)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/13225. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Cousin, John William (1910). "Higden, Ranulf or Ralph". A Short Biographical Dictionary of English Literature. London: J. M. Dent & Sons – via Wikisource.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Cousin, John William (1910). "Higden, Ranulf or Ralph". A Short Biographical Dictionary of English Literature. London: J. M. Dent & Sons – via Wikisource.

External links

- Full text of the Polychronicon and Trevisa's English translation in Google Books

- Polychronicon, 091 H534 at L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Brigham Young University

- Works by or about Ranulf Higden at Internet Archive

- Works by Ranulf Higden at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)