| Reconquista | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Napoleonic Wars | |||||||||

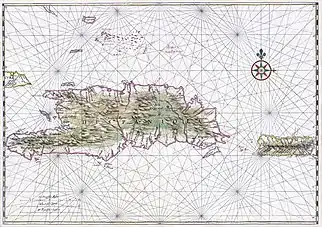

Map of Hispaniola and Puerto Rico | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

2,000 6 frigates | 2,600 | ||||||||

Spanish reconquest of Santo Domingo (Spanish: Reconquista Española de Santo Domingo) was the war for Spanish reestablishment in Santo Domingo, or better known as the Reconquista, and was fought between November 7, 1808, and July 9, 1809. In 1808, following Napoleon's invasion of Spain, the criollos of Santo Domingo revolted against French rule and their struggle culminated in 1809 with a return to the Spanish colonial rule for a period commonly termed España Boba.

Background

Treaty of Basel

.svg.png.webp)

The war between Spain and the Convention ended with the cession of the eastern part of the island of Santo Domingo to France, in exchange for the return of the peninsular territories occupied by the French army, as stipulated in the Treaty of Basel, signed on July 22, 1795 between both countries. The situation of general chaos in which the French part of the island was immersed, due to the uprising of the slaves and the struggles unleashed between the various ethnic and social groups, caused the sine day postponement of the definitive handover of the colony by the Spanish authorities to the French ones. However, the consequences of the news were not long in coming, and a large number of Dominican families left the island bound for Puerto Rico, Cuba and Venezuela in a migration process that increased when soldiers commanded by Toussaint Louverture, a former slave who had become general of the French Republic, entered Santo Domingo almost without resistance, in 1801, to take possession of the territory that Spain had ceded to France. The expedition sent by Napoleon Bonaparte to the island in 1802, headed by General Charles Leclerc, did not manage to restore order, but rather lost control over the western part of the island, in which French rule was already more virtual than real, unlike of what was happening in Santo Domingo, whose population supported the new authorities as a safeguard against their neighbors to the west. After the proclamation of Haitian independence in 1804, the eastern part remained under the power of France.

French occupation

During the French era in Santo Domingo, from 1802 and especially from 1804, there were undoubtedly convinced Francophiles among the Dominicans. The brilliance of Napoleonic France was perceived and had its effects in the country. After the failed invasion of Jean-Jacques Dessalines in 1805, it was realized that a competent and progressive administration was beginning; It was noted that the French governor, General Jean-Louis Ferrand, was a capable and well-intentioned man.[1]

During his government, the French took care of the reconstruction and consolidation of the Colony. Ferrand launched proclamations abroad calling on the French to live in Santo Domingo; Many responded to the call, as did some Spanish families, and thus things continued to improve incredibly after so many vicissitudes. In Samaná, for example, which until then had been a poor and forgotten village, the Government encouraged the planting of coffee plantations that already in 1808 promised to give new life to this region, whose French population grew so much that Ferrand even had the plans prepared. of a modern city that would be named Port Napoleon. The wood forests, which until then had been exploited very sporadically, were subject to regular exploitation, since the Island's mahogany, due to its beauty, was in great demand in the United States and Europe. Taxes were reduced to the minimum in order to help the inhabitants of the Colony recover their fortunes.[1]

Ferrand established a paternal government, supported by a decree from Napoleon in 1803, through which he ordered respect for Spanish uses and customs, especially as far as the legal organization was concerned. The truth was that there was collaboration between the population and the authorities, although Ferrand, convinced that Hispanic feelings were still alive among the vast majority of the population, avoided, as much as possible, the opportunities to make them feel his power.[1]

French invasion of Spain

That same year, Napoleon invaded Spain, leading to Tlthe abdication of King Charles IV as a consequence of the Aranjuez mutiny, and the proclamation of Ferdinand VII caused a dynastic and political crisis that was used by Napoleon, whose troops had entered Spain heading towards Portugal, to confine the entire royal family in Bayonne, and put his brother José on the Spanish throne. Following the outbreak of the popular uprising against the French invasion, in May 1808, there was a subsequent reaction in the Spanish territories of America, in favor of the cause of the deposed Ferdinand VII.

This news reached Santo Domingo from Puerto Rico, whose authorities were informed early of the events. However, it was not until the end of July 1808 that the governor of Puerto Rico received official information of the declaration of war on France by the Provincial Board of Asturias. As is known, this declaration was followed by others proclaimed by the new provincial boards that were formed throughout Spain to combat the French. Immediately after the governor of Puerto Rico had the formal declaration of war in his hands, he sent a copy of it to the French governor in Santo Domingo also declaring war.

Preparations for war

In Santo Domingo, particularly, where the French ruled over a population that still considered itself Spanish, Napoleon's betrayal against the monarchs of Spain provoked the indignation of the most important property owners who now considered themselves doubly humiliated by knowing that the "Motherland" had fallen under French rule and saw its businesses damaged by the prohibition on selling its livestock to Haitians. Some of them, as was the case of Juan Sánchez Ramírez, a rich owner of herds and mahogany fields in the surroundings of Cotuí and Higüey, were extremely indignant and thought of obtaining the collaboration of the Governor of Puerto Rico, and the Dominican population that had emigrated to that island, to fight against the French of Santo Domingo in the same way that the Spanish would fight to expel the invaders from the Peninsula.[2]

Sánchez Ramírez was born in 1762 in the Cotuí region, and in his youth, at the head of a company of lancers formed by him with fellow citizens, he had fought during the time of Governor Joaquín García against the French Republic. He emigrated to Puerto Rico in December 1803, but he found it necessary to return to his homeland in 1807, when he began his work of gaining followers for the Reconquista, while at the same time he dedicated himself to the exploitation of wood cuts in some possessions. theirs located on the eastern coasts between Higüey and Jobero (current Miches, also known as Jovero), from where communications with Puerto Rico were easier.[2]

He was visiting the towns in the eastern part of the colony with the intention of organizing an uprising to attack the city of Santo Domingo and expel the French from the island. Since Sánchez Ramírez learned of the fall of the Spanish monarchs, he set out to avenge the Napoleonic invasion. According to what he says in his Diary: "from that moment on I could not shake the idea of war from my imagination... and that encounter produced such resentment in my spirit against them that, despite the acceptance that I owed them, they even called me themselves the friend of the French, I could not see them from then on without becoming extremely irritated."[2]

Battle of Palo Hincado

On November 6, Sánchez Ramírez advanced to Magarín and it seemed to him that the site had not been well chosen by Lieutenant Francisco Díaz. Furthermore, a strong storm damaged the few firearms and ammunition he had at his disposal. Appreciating that the area of Palo Hincado, half a league west of the town of Seibo, had better conditions, he took his people there and issued orders to wait firmly for the enemy.[1]

Momentarily not trusting Díaz, he decided to take all the arrangements alone on the night of the 6th, the eve of the date announced by Ferrand for his entry into the Seibo. The rain did not stop, with all its adverse consequences. In the early hours of the 7th, the Candelaria herd cleared them and Sánchez Ramírez had the rifles dried over the fire, the troops were given ammunition and the horsemen were provided with spears, ready to combat “the fury and rage of the Napoleons that infested the Primacy of the Indies for the infamy of a denatured Spaniard.”[1]

The reconquistadors arrived at Palo Hincado between nine and ten in the morning. Sánchez Ramírez placed Francisco Díaz in a position of trust at the top of the terrain, in front of the almost three hundred combatants who carried rifles. He then settled in the same place with his general staff, issuing orders to conveniently distribute his troops.[1]

Among many other measures he took that of ordering José de la Rosa to ambush himself with thirty riflemen in the enemy's rear to distract their attention after the fire broke out in the front. De la Rosa had been one of those who arrived in Boca de Yuma on October 29, from Puerto Rico.[1]

Located in the center of his army, on the aforementioned eminence, the brigadier placed Manuel Carvajal on his right and Pedro Vásquez on his left. Miguel Febles served as his senior assistant.[1]

From that place he harangued the troops. He warned him that the action was going to be decisive, since with the governor himself coming at the head of the enemy expedition, with the best of the forces at his disposal, his defeat would mean the triumph of the campaign. He recommended assaulting the knife after the first volley, to avoid the effect of the better musketry and tactics of the French. He ended the speech by announcing that he would apply the death penalty to the soldier who turned his face away; to the drum to beat retreat and to the officer to order it, even if it was himself. In this way he forced everyone, including him, to think that it was better to die fighting than to be dishonorably shot. His final exclamation was a cheer to Ferdinand VII, the prince who at that time personified the best Spanish hopes.[3]

The leader's harangue was followed by tense moments of silence and attention. The French advanced and broke fire around noon. A Gallic cavalry advanced to cut off the Spanish-Creole left. The horsemen led by Captain Antonio Sosa did not waste time and ran to meet her, forcing the attackers to pull on the bridle. This first hand-to-hand clash was bloody. Sánchez Ramírez gave the cavalry of his right wing, led by Captain Vicente Mercedes, the order to advance, an operation that was carried out very quickly, overwhelming the enemy. Ten minutes of fighting were enough for the field to be covered with French corpses.[3]

The tactic of the Hispanic-Creoles consisted, as stated in the diary of Sánchez Ramírez, in quickly converting the duel with bullets from a distance into hand-to-hand combat, in which the seasoned Dominicans were skilled. They executed it with such alacrity and daring that only seven of them died. Among these, significantly, the heads of the two cavalry corps, captains Antonio Sosa and Vicente Mercedes.[3]

Seeing his battalions destroyed, General Ferrand ordered a hasty return to Santo Domingo with a group of surviving officers. He was pursued by a squad led by Colonel Pedro Santana (father of the homonymous future leader of the Dominican Republic). The fugitives gained distance by venturing to cross a torrent that the pursuers did not risk crossing, which allowed them to stop to rest in the Guaiquía ravine. In this place the unhappy Ferrand, dominated by despondency as the Dominicans rebels were closing in, took his life with a gunshot to the head.[3] The capital was now officially under siege.

Battle for Santo Domingo

The Siege of Santo Domingo of 1808 was the second and final major battle and was fought between November 7, 1808, and July 11, 1809, at Santo Domingo, Colony of Santo Domingo. A force of Dominican and Puerto-Rican of 1850 troops led by Gen. Juan Sánchez Ramírez, with a naval blockade by British Commander Hugh Lyle Carmichael, besieged and captured the city of Santo Domingo after an 8 months siege of the 2000 troops of the French Army led by Gen. Barquier.

British involvement

British Major General Hugh Lyle Carmichael departed Jamaica with the 2nd West Indian, 54th, 55th, and Royal Irish regiments to aid Britain's new found Spanish allies in reducing the isolated French garrison besieged in south-eastern Hispaniola. His convoy was escorted by Capt. William Price Cumby's HMS Polyphemus, Aurora, Tweed, Sparrow, Thrush, Griffin, Lark, Moselle, Fleur de la Mer, and Pike. Carmichael disembarked at Palenque (50 km or 30 mi west of Santo Domingo) on 28 June, hastening ahead of his army to confer with his Spanish counterpart— General Juan Sánchez Ramírez, commander of a Puerto Rican regiment and numerous local guerrillas—who for the past eight months had been investing the 1,200-man French garrison commanded by Brig. Gen. Joseph-David de Barquier.

Despite 400 of the 600 Spanish regulars being sick, they advanced on 30 June at Carmichael's behest to seize San Carlos Church on the outskirts of the capital and cut off communication between Santo Domingo and Fort San Jerónimo 3 km (2 mi) west, while simultaneously securing a beach for Cumby's supporting squadron. The demoralized French defenders had already requested an armistice and been rebuffed, repeating the suggestion on 1 July as the first British troops arrived overland (hampered by torrential rains). As negotiations progressed Carmichael maintained pressure by installing heavy siege batteries around the city and massing his forces for an assault.

French surrender

On 6 July the capitulation was finalized, de Barquier pointedly surrendering to the British rather than to the Spaniards. The next day British troops occupied the city and Fort San Jerónimo, the French defenders being transported directly to Port Royal, Jamaica without loss of life on either side.

Aftermath

The situation of shortage of the colonial treasury continued throughout the known period in Dominican historiography known as España Boba. This would last until 1821, with the bloodless proclamation of the Republic of Spanish Haiti by José Núñez de Cáceres. Although this was short lived, as Haitian forces invaded the newborn nation, beginning the Haitian domination period. 22 years later, on 27 February 1844, Dominican revolutionaries Juan Pablo Duarte, Francisco del Rosario Sánchez, and Matías Ramón Mella declared the independence of the Dominican Republic. For its part, Spain lost control of a territory whose great geostrategic importance, during to its proximity to Cuba and Puerto Rico, would have served Spain's greater interest as a metropolis. This wouldn't be preserved until Pedro Santana decided to re-annex the country in 1861, before being permanently ousted by Gregorio Luperon in the Dominican Restoration War.

See also

References

- Delafosse, Lemonier; "Second Campaign of Santo Domingo — Dominican-French War of 1808" (translation of C. Armando Rodriguez); Editorial El Diario, Santiago (DR); 1946.

- Guillermin, Gilbert; "Journal History of the Spanish revolution of Santo Domingo" (translation C. Armando Rodriguez); Dominican Academy of History; Imp editing PV Lafourcade, Philadelphia, U.S.; 1810.

- Sánchez Ramírez, Juan; " Journal of the Reconquista"; Editor Montalvo, Santo Domingo (R.D.); 1957.

Bibliography

- Marley, David. Wars of the Americas: A Chronology of Armed Conflict in the New World, 1492 to the PresentABC-CLIO (1998). ISBN 0874368375