| Red-tailed amazon | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Psittaciformes |

| Family: | Psittacidae |

| Genus: | Amazona |

| Species: | A. brasiliensis |

| Binomial name | |

| Amazona brasiliensis | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Psittacus brasiliensis Linnaeus, 1758 | |

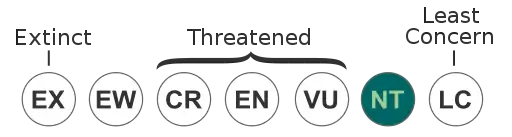

The red-tailed amazon (Amazona brasiliensis), also known as the red-tailed parrot, is a species of parrot in the family Psittacidae. It is endemic to coastal regions in the south-east Brazilian states of São Paulo and Paraná. The bird has been threatened by habitat loss and capture for the wild bird trade, and is a symbol of the efforts to conserve one of the Earth's most biologically diverse ecosystems. Consequently, it is considered Near Threatened by BirdLife International and the IUCN. In 1991–92, the population had fallen below 2000 individuals. Following on-going conservation efforts, a count and estimate from 2015 suggests a population of 9,000–10,000, indicating that this species is recovering from earlier persecution.[1] A recent study shows that the population of this species is stable at Paraná state, Southern Brazil, revealing population trend fluctuation during the last 12 years.[3]

Taxonomy

In 1751 the English naturalist George Edwards included an illustration and a description of the red-tailed amazon in the fourth volume of his A Natural History of Uncommon Birds. He used the English name "The Brasilian green parrot". Edwards based his hand-coloured etching on a live bird that was displayed at the shop of a bird-cage maker in London.[4] When in 1758 the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus updated his Systema Naturae for the tenth edition, he placed the red-tailed amazon with the other parrots in the genus Psittacus. Linnaeus included a brief description, coined the binomial name Psittacus brasiliensis and cited Edwards' work.[5] The red-tailed amazon is now one of around 30 parrots placed in the genus Amazona that was introduced by the French naturalist René Lesson in 1830.[6][7]

Description

.jpg.webp)

Red-tailed amazons weigh around 425 g (15.0 oz) and are approximately 35 cm (14 in) long. As expected from its common name, it has a broad red band on its tail, but as it largely is limited to the inner webs of the feathers, it is mainly visible from below or when the tail is spread open. Additionally, the tail has a broad yellow tip, and the outer rectrices are dark purplish-blue at the base. The remaining plumage is green, while the throat, cheeks and auriculars are purple-blue, the forecrown is red, and the rectrices are broadly tipped dark blue. It has a yellowish bill with a blackish tip to the upper mandible, a pale gray eye ring, and orange irises. Juveniles have a duller plumage and brown irises.

Habitat

The red-tailed amazon is associated with the Atlantic Forest system, and lives in forests, woodlands and mangroves near the coast. This species is almost entirely restricted to lowlands, typically occurring at altitudes below 200 meters (660 feet) above sea-level, though sometimes reaching altitudes up to 700 m (2,300 ft).[8]

Behavior

Red-tailed amazons are usually found in pairs or flocks, which occasionally may number several hundred individuals in the non-breeding season. It primarily roosts and breeds on coastal islands, but most of the foraging takes place on the nearby mainland, where the birds forage mainly for fruits, but their diet also includes seeds, flowers, nectar, and rarely, insects.

Breeding

The red-tailed amazon breeds in mangrove and coastal forests on islands. The breeding season lasts from September to February, when the parrots lay three or four eggs in a natural tree-cavities. The incubation period is 27 to 28 days, and the fledging period an additional 50 to 55 days.[9]

Threats

Loss of habitat

Brazil's recent industrialization, accompanied by intense economic and population growth, is largely responsible for the parrot's endangered status. Every year extensive logging wipes out pristine plots of land once home to thousands of plant, insect, and animal species. Land areas equivalent in size to small countries are wiped out in a matter of months. This ongoing logging continues to destroy habitat and threaten the bird's limited geographic range. Extensive logging also destroys the native plant species that provide food and shelter for the birds. As a result, the birds are forced to relocate to less suitable areas. Frequently, the parrots are unable to locate food and perish.

Habitat destruction is one of the main forces driving the red-tailed amazon to extinction. Brazil's increasing demand for lumber, agriculture, and housing developments has caused the forests to be cleared at an unprecedented rate. In fact, ninety-three percent of the original Atlantic coastal forest, which is the bird's main habitat, has been cleared. Now, the seven percent of land that remains is so fragmented by paths and roads that the large flocks of birds have difficulty finding enough food in any one strip. This fragmentation is particularly devastating to the birds since they only forage in a 4700 km strip, between Rio de Janeiro and Curituba.

Fragmentation not only limits food sources but also creates additional problems for the birds. As the development of roads and residential areas continue, the remaining land becomes so fragmented that the parrots are forced to live in edge habitats. These edge habitats leave nest sites vulnerable to both human and animal predation.[10]

Poaching

Habitat destruction is not the only reason the birds are endangered. Animal trafficking also threatens the red-tailed amazon. According to the World Wildlife Fund, "animal trafficking is the third largest illegal trade in the world behind illicit drug and arms sales, totaling $1.5 billion annually in Brazil alone."

Red-tailed amazons are a particularly easy target for traffickers thanks to their vibrant colors and isolated breeding grounds.[11] One study noted that of forty-seven nests monitored between 1990 and 1994, forty-one were robbed by humans.[12] Rural, low income Brazilians are desperate for money and catch the birds for dealers. In turn, the dealers pay the locals $30 per bird and turn around and sell the birds for $2,500 a piece to buyers.[13]

Wild game collectors, many of them Brazilians, want the birds for live trophies, pets, or as additions to their private zoos.[13] Part of what makes animal trafficking so harmful to the parrots is the destructive nature of the process. Often, traffickers damage the fragile nests while removing the birds. This damage prevents future nesting and forces the birds to rebuild elsewhere.

Once the birds are removed the situation only gets worse. Traffickers smuggle the birds across borders in containers too small to properly hold them. As a result, many parrots die along the journey from thirst, starvation, broken limbs, or simply from fright. Fatality numbers are astounding: nine out ten parrots transported die before reaching their final destination.[13]

The ineffectiveness of animal trafficking creates a vicious cycle. Several birds are plucked from the forest because so few reach their destination. As a result, the birds become increasingly difficult to find. Consequently, invasion into the forests for trafficking becomes more frequent, which further threatens the ecosystem and its wildlife.

Conservation

Education and resources

A number of steps are being taken to ensure the parrots' safety. One program aimed at educating locals on the importance of the birds is already underway. Established in 1997, the Environmental Education Program for the Conservation of the Red-tailed Amazon focuses on reducing threats to the bird through educational programs.[8]

Working specifically with students, women and artists, the Environmental Education Program hosts several workshops and field trips to promote awareness about the endangered red-tailed amazon. The program hopes these workshops and field trips will illustrate the importance of conservation and consequently reduce logging and animal trafficking.[13]

An additional step to ensure the birds’ safety was the establishment of ex-situ facilities, specifically zoos. Research shows that red-tailed amazons breed moderately well in captivity. There are already successful captive-breeding programs in the European Union and Brazil.[14] Breeding programs at Chester Zoo and the UK Rode Tropical Bird Garden have both successfully bred the red-tailed amazon.[15]

Possibly one of the most significant steps taken to save the parrots was the establishment of Superagui National Park in 1989. Although the park wasn't established solely with the birds’ safety in mind, the park does provide an excellent safe haven for the red-tailed amazon and thousands of plant and animal species alike. The over 34,254 hectares of lush forest, which is part of the largest continuous stretch of intact Atlantic rainforest, is one of the most important protected areas within this Brazil.[16]

Legislation

Measures to stop the illegal trafficking of the parrots into the United States have also been taken. The United States Endangered Species Act (ESA) and The United States Fish and Wildlife Service act as the red-tailed amazon's greatest protection against illegal transportation to the US. Because the bird is listed as endangered under this act, if imported illegally into the U.S. the bird will be confiscated and its carrier will be punished. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service seeks to prevent illegal importation of animals by setting up search sites in airports. Luggage is search manually and many times trained dogs are brought in to search the bags for any trace of animals.[17]

The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) also affords the species protection from international trade by listing it under Appendix I, the strictest degree of protection.[18]

The ESA and CITES are the red-tailed amazons primary governmental protection. They control the trade of individuals to an extent; however, often the laws are not adequately enforced.

Importance

Red-tailed amazons play a vital role in seed dispersal. Because the birds cover extensive areas while feeding, they are tremendous seed dispersers. As the birds migrate between the Atlantic mainland and the coastal islands they disperse seeds via their droppings. Seed distribution of this extent helps create and maintain biodiversity in the mainland and islands.[13][19]

The birds also indirectly provide Brazilians with a source of income. Excursions near the birds’ breeding islands offer birdwatchers the opportunity to watch the birds in flight. Some tourists come see the parrot's migration, while others simply come to see them in place.

References

- 1 2 BirdLife International (2017). "Amazona brasiliensis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2017: e.T22686296A118478685. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-3.RLTS.T22686296A118478685.en. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

- ↑ "Appendices | CITES". cites.org. Retrieved 2022-01-14.

- ↑ Sipinski, Elenise; Abbud, Maria Cecilia; Sezerban, Rafael Meireles; Serafini, Patricia Pereira; Boçon, Roberto; Manica, Lilian Tonelli; Guaraldo, André de Camargo. "Tendência populacional do papagaio-de-cara-roxa (Amazona brasiliensis) no litoral do estado do Paraná". Ornithologia. 146 (2): 136–143. Archived from the original on 2018-10-04.

- ↑ Edwards, George (1751). A Natural History of Uncommon Birds. Vol. Part 4. London: Printed for the author at the College of Physicians. p. 161, Plate 161.

- ↑ Linnaeus, Carl (1758). Systema Naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin). Vol. 1 (10th ed.). Holmiae (Stockholm): Laurentii Salvii. p. 102.

- ↑ Lesson, René (1831). Traité d'Ornithologie, ou Tableau Méthodique (in French). Vol. 1. Paris: F.G. Levrault. p. 189.

- ↑ Gill, Frank; Donsker, David; Rasmussen, Pamela, eds. (July 2021). "Parrots, cockatoos". IOC World Bird List Version 11.2. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 16 October 2021.

- 1 2 (BirdLife International)

- ↑ (ARKive)

- ↑ (Birdlife International)

- ↑ Martuscelli, Paulo (1995). "Ecology and conservation of the Red-tailed Amazon Amazona brasiliensis in south-eastern Brazil". Bird Conservation International. 5 (2–3): 405–420. doi:10.1017/S095927090000112X.

- ↑ (Genetic Variability in the Red-tailed Amazon)

- 1 2 3 4 5 (The Problems)

- ↑ (The Parrot Society UK)

- ↑ (Chester Zoo)

- ↑ (ParksWatch)

- ↑ (The United States Fish and Wildlife Service)

- ↑ (CITES)

- ↑ Climate Change - Health and Environmental Effects. The United States Environmental Protection Agency (October 15, 2009). Retrieved September 15, 2010

- Alexandre B. Sampaio, Karen D. Holl, and Aldicir Scariot. 2007. Regeneration of Seasonal Deciduous Forest Tree Species in Long-Used Pastures in Central Brazil. Biotropica 39(5): 655–659.

- Amazona brasiliensis. Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Washington, D.C. (accessed March 2008).

- Breeding Brasiliensis in Brazil. The Parrot Society UK. Herts, England. (accessed April 2008).

- Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora. Geneva, Switzerland. (accessed April 2008).

- Conserving the Nature of America. The United States Fish and Wildlife Service, Honolulu, Hawaii.

- Martin, M., and M. Sa. 1999. Conservation Status of parrot populations in an Atlantic rainforest area of southeastern Brazil. Biodiversity and Conservation 8:1079-1088.

- Martuscelli, P. 2006. Genetic Variability in the Red-tailed Amazon (Amazona brasiliensis Psittaciformes) Assessed by DNA fingerprinting. Revista Brasileria de Ornitologia 14 (1) 15–19.

- Red-tailed Amazon. ARKive, Bristol (accessed March 2008).

- Red-tailed Amazon - BirdLife Species Factsheet. BirdLife International, Cambridge, United Kingdom. (accessed February 2008).

- Amazon Parrot. Chester Zoo. Chester, England. Available from (accessed April 2008).

- Superagüi National Park. ParksWatch. Durham, N.C. (accessed April 2008).

- The Problems. Red Tailed Parrot. (accessed April 2008).

- Sipinski, E.A.B, Abbud, M.C., Sezerban, R.M., Serafini, P.P., Boçon R., Manica, L.T., and Guaraldo, A.C. 2014.Tendência populacional do papagaio-de-cara-roxa (Amazona brasiliensis) no litoral do estado do Paraná . Ornithologia 6: 136–143.