| Giant oarfish | |

|---|---|

| |

| A taxidermied specimen of Regalecus glesne in Naturhistorisches Museum Wien | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Lampriformes |

| Family: | Regalecidae |

| Genus: | Regalecus |

| Species: | R. glesne |

| Binomial name | |

| Regalecus glesne Ascanius, 1772 | |

| Synonyms [2] | |

|

Synonyms

| |

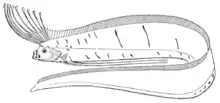

The giant oarfish (Regalecus glesne) is a species of oarfish of the family Regalecidae. It is an oceanodromous species with a worldwide distribution, excluding polar regions. Other common names include Pacific oarfish, king of herrings, ribbonfish, and streamer fish.[3]

R. glesne is the world's longest ray-finned fish. Its shape is ribbon-like, narrow laterally, with a dorsal fin along its entire length, stubby pectoral fins, and long, oar-shaped pelvic fins, from which its common name is derived.[4] Its coloration is silver and blue with spots of dark pigmentation, and its fins are crimson.[5] Its physical characteristics and undulating mode of swimming have led to speculation that it might be the source of many "sea serpent" sightings.[3]

Taxonomy

R. glesne was first described by Peter Ascanius in 1772. The genus name, Regalecus, signifies "belonging to a king"; the specific epithet glesne is from "Glesnaes", the name of a farm at Glesvær (not far from Norway's second largest city of Bergen), where the type specimen was found.[6]

Its "king of herrings" nickname may derive from its crownlike appendages and from being sighted near shoals of herring, which fishermen thought were being guided by this fish.[7] Its common name, oarfish, is probably an allusion to the shape of its pelvic fins, or else it may refer to the long slender shape of the fish itself.[3]

Distribution

The giant oarfish has a worldwide distribution, having been found as far north as 72°N and as far south as 52°S, but is most commonly found in the tropics to middle latitudes.[8] It has been categorized as oceanodromous, following its primary food source.[9] It is thought to inhabit the sunlit epipelagic to dimly lit mesopelagic zones, ranging as deeply as 1,000 m (3,300 ft) below the surface.[10]

Morphology

This species is the world's longest bony fish, reaching a record length of 8 m (26 ft); however, unconfirmed specimens of up to 11 m (36 ft) have been reported.[11] It is commonly measured to 3 m (9.8 ft) in total length.[12]

Few R. glesne larvae have been identified and described in situ. These larvae exhibit an elongated body with rays extending from the occipital crest and a long pelvic fin.[13] Unlike the adult form of the species, the skin of the larvae is almost entirely transparent with intermittent spots of dark coloration along the organism's dorsum.[13] Additionally, the larvae possess a caudal fin with four fin rays, which is a trait not present in the adult form of the species.[13]

Adults have a ribbonlike shape that is laterally narrow, with a dorsal fin along its entire length from between its eyes to the tip of its tail. The dorsal fin rays are soft and number between 414 and 449 in total.[5] At the head of the fish, the first 10–12 of these dorsal fin rays are lengthened, forming the distinctive red crest associated with the species.[5] Its pectoral and pelvic fins are nearly adjacent. The pectoral fins are stubby while the pelvic fins are long, single-rayed, and reminiscent of an oar in shape, widening at the tip. Its head is small with the protrusible jaw typical of lampriformes.[4] The species has 33 to 47 gill rakers on the first gill arch, and no teeth.[4]

The organs of the giant oarfish are concentrated toward the head end of the body, possibly enabling it to survive losing large portions of its tail.[14] It has no swim bladder. The liver of R. glesne is orange or red, the likely result of astaxanthin in its diet.[15] The lateral line begins above and behind the eye then, descending to the lower third of the body, extends to the caudal tip.[16]

Life cycle

Much of what is known about the juvenile life cycle of R. glesne comes from artificial insemination work done in a laboratory setting.[17] This work was performed in 2020 and was the first time that the progression from fertilized eggs to larvae was observed. Post-fertilization, the eggs took 18 days to hatch into larvae. They noted that the larvae appeared similar to other lampridiform larvae, facing downward with pectoral fins. The larvae then died four days later, so this study spanned only the early life cycle of the species.[17]

In the field, the species is known to spawn from July to December. The resulting eggs are 2.5 mm (0.1 in) large,[18] and float near the surface until hatching. Its larvae are also observed near the surface during this season.[14]

Behavior

Little is known about oarfish behavior. It has been observed swimming by means of its dorsal fin, and also swimming in a vertical position.[10] In 2010, scientists filmed a giant oarfish in the Gulf of Mexico swimming in the mesopelagic layer, the first footage of a reliably identified R. glesne in its natural setting. The footage was caught during a survey, using an ROV in the vicinity of Thunder Horse PDQ, and shows the fish swimming in a columnar orientation, tail downward.[19]

Relationship with humans

R. glesne is not fished commercially, but it is an occasional bycatch in commercial nets.[2][14]

Due to their size, elongated bodies, and undulating swimming pattern, giant oarfish are presumed to be responsible for some sea serpent sightings.[21] Formerly considered rare, the species is now suspected to be relatively common, although sightings of healthy specimens in their natural habitat are unusual.[14]

The giant oarfish, and the related R. russelii, are sometimes known as "earthquake fish" because they are popularly believed to surface before and after an earthquake.[22][23]

References

- Citations

- ↑ Smith-Vaniz, W. F. (2015). "Regalecus glesne". The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-4.RLTS.T190378A21911480.en.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - 1 2 Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2013). "Regalecus glesne" in FishBase. February 2013 version.

- 1 2 3 Helfman, Gene S. (1 June 2015). "Secrets of a sea serpent revealed". Environmental Biology of Fishes. 98 (6): 1723–1726. doi:10.1007/s10641-015-0380-x. ISSN 1573-5133. S2CID 17197827.

- 1 2 3 R., Roberts, Tyson (2012). Systematics, biology, and distribution of the species of the oceanic Oarfish genus Regalecus Teleostei, Lampridiformes, Regalecidae. Publications Scientifiques du Muséum. ISBN 978-2-85653-677-3. OCLC 835964768.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - 1 2 3 Smith, Margaret M. (1986). Smiths' Sea Fishes. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg. p. 403. ISBN 978-3-540-16851-5.

- ↑ Jordan, David Starr; Evermann, Barton W. (1898). "Fishes of North and Middle America: 2971. Regalecus glesne". Bulletin of the United States National Museum. 3 (47): 2596–2597. Retrieved 3 March 2013.

- ↑ Minelli, Alessandro; Minelli, Maria P. (1997). Great Book of Animals: the Comprehensive Illustrated Guide to 750 Species and their Environments. Philadelphia, Pa.: Courage Books. p. 102. ISBN 0-7624-0137-0.

- ↑ Fischer, W (1987). Fiches FAO d'identification des especes pour les besoins de la peche : Mediterranee et mer Noire. FAO. OCLC 221565695.

- ↑ Schmitter-Soto, Juan J. (2008). "The Oarfish, Regalecus glesne (Teleostei: Regalecidae), in the Western Caribbean". Caribbean Journal of Science. 44 (1): 125–128. doi:10.18475/cjos.v44i1.a13. ISSN 0008-6452. S2CID 86124978.

- 1 2 Benfield, M. C.; Cook, S.; Sharuga, S.; Valentine, M. M. (2013). "Five in situ observations of live oarfish Regalecus glesne (Regalecidae) by remotely operated vehicles in the oceanic waters of the northern Gulf of Mexico: in situ observations of regalecus glesne". Journal of Fish Biology. 83 (1): 28–38. doi:10.1111/jfb.12144. PMID 23808690.

- ↑ McClain, Craig R.; Balk, Meghan A.; Benfield, Mark C.; Branch, Trevor A.; Chen, Catherine; Cosgrove, James; Dove, Alistair D.M.; Gaskins, Leo C.; Helm, Rebecca R. (13 January 2015). "Sizing ocean giants: patterns of intraspecific size variation in marine megafauna". PeerJ. 3: e715. doi:10.7717/peerj.715. ISSN 2167-8359. PMC 4304853. PMID 25649000.

- ↑ W.., Fischer, W.. Krupp, F.. Schneider (1995). Pacifico centro-oriental. Organizacion de las naciones unidas para la agricultura y la alimentacion. ISBN 92-5-303408-4. OCLC 492126474.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - 1 2 3 Dragičević, Branko; Pallaoro, Armin; Grgičević, Robert; Lipej, Lovrenc; Dulčić, Jakov (1 July 2011). "On the Occurrence of Early Life Stage of the King of Herrings, Regalecus Glesne (Actinopterygii: Lampriformes: Regalecidae), in the Adriatic Sea". Acta Ichthyologica et Piscatoria. 41 (3): 251–253. doi:10.3750/AIP2011.41.3.13.

- 1 2 3 4 Burton, Maurice; Burton, Robert (2002). International Wildlife Encyclopedia (3rd ed.). New York: Marshall Cavendish. pp. 1767–1768. ISBN 0-7614-7279-7.

- ↑ Fox, Denis L. (1976). Animal Biochromes and Structural Colours: Physical, Chemical, Distributional & Physiological Features of Coloured Bodies in the Animal World (2d ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 141. ISBN 0-520-02347-1.

- ↑ Ruiz, Ana E.; Gosztonyi, Atila E. (2010). "Records of regalecid fishes in Argentine waters" (PDF). Zootaxa. 2509: 62–66. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.2509.1.5. ISSN 1175-5334. S2CID 16545315. Retrieved 15 March 2013.

- 1 2 Oka, Shin-ichiro; Nakamura, Masaru; Nozu, Ryo; Miyamoto, Kei (8 April 2020). "First observation of larval oarfish, Regalecus russelii, from fertilized eggs through hatching, following artificial insemination in captivity". Zoological Letters. 6 (1): 4. doi:10.1186/s40851-020-00156-6. ISSN 2056-306X. PMC 7140580. PMID 32292594.

- ↑ Hureau, J. C. (ed.). "Oar fish (Regalecus glesne)". Fishes of the NE Atlantic and the Mediterranean. Retrieved 3 March 2013 – via Marine Species Identification Portal.

- ↑ Bourton, Jody (8 February 2010). "Giant bizarre deep sea fish filmed in Gulf of Mexico". BBC News. Retrieved 16 March 2013.

- ↑ Carstens, John (April 1997). "SEALS find serpent of the sea" (PDF). All Hands. Naval Media Center. pp. 20–21. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

- ↑ Ellis, Richard (2006). Monsters of the Sea (1st Lyons Press ed.). New York, NY: Lyons Press. p. 43. ISBN 1592289673.

- ↑ Lallanilla, Marc (22 October 2013). "Can Oarfish Predict Earthquakes?". Livescience.com.

- ↑

Yamamoto, Daiki (4 March 2010). "Sea serpents' arrival puzzling, or portentous?". Kyodo News. Retrieved 6 March 2010.

TOYAMA — A rarely seen deep-sea fish regarded as something of a mystery has been giving marine experts food for thought recently after showing up in large numbers along the Sea of Japan coast.

External links

- Giant 'Sea Serpent' Caught on Camera, Discovery News at YouTube. Footage of an oarfish swimming in the mesopelagic layer.

- "Mythical sea creature captured on film", article about efforts to ban deep-sea bottom trawling with video of R. glesne

- Recent Examinations of the Oarfish, Regalecus glesne, from the North Sea. Yorkshire Coast Sealife, Fisheries & Maritime Archive & Museum