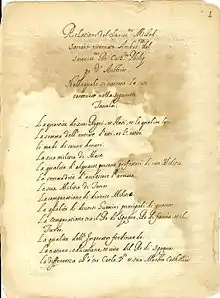

Relazioni (Italian for reports or accounts; singular relazione) were the final reports presented by Venetian ambassadors of their service in foreign states. Relazioni contained descriptions of the current political, military, economic, and social conditions of the country visited. Relazioni are important to historians for recording the development of diplomacy in early modern Europe.

Background

During the fourteenth, fifteenth, and sixteenth centuries, Italian states cultivated commercial, diplomatic, and political relations with first the Turkoman emirates of western Anatolia, and then the Ottomans (as well as other eastern Mediterranean states) as part of their multifaceted to maintain long-established trading empires and to keep the Ottoman armies out of the Italian peninsula.

- — Daniel Goffman, "Negotiating with the Renaissance State: The Ottoman Empire and the New Diplomacy"[1]

Out of all the Italian states, the Venetians and the state of Venice faced these threats the most directly because the Ottoman armies and navies began to push up and into the Adriatic Sea. The military threat of the Ottoman Empire loomed large within Italian consciousness, but the government of the Republic of Venice knew that its commerce depended less and less on its own natives and armies and more and more on its good relations with the Ottoman Empire. As a result, this forced Venice to feel the need to an Ottoman world in the making because the Ottoman Empire had been expanding so rapidly at the time.

There were very many Venetian merchants that lived within the Ottoman Empire which made the state of Venice feel a need to protect their merchants in the "foreign" and "fearful" places under Ottoman rule. The Venetians sought to do so by appointing permanent representatives known as consuls, better known as ambassadors, whose job was to shield their subjects in the "foreign" state and describe in frequent letters the happenings within the Ottoman state. This system is thought to have been the beginning of the development of modern diplomacy in Europe. Upon their return to the Venetian state, these permanent representatives would present the happenings that they witnessed within the Ottoman Empire to the Republic in a document known as relazione. Beginning in 1454, an appointed permanent representative always resided in the Ottoman State (usually in the Ottoman capital).

Contents and the Significance Relazioni

The Relazione provided a broad and comprehensive synthesis, periodically brought up to date by successive ambassadors, of the political military, economic, and social conditions of the country visited.

- — Donald E. Queller, "The Development of Ambassadorial Relazioni"[2]

A fully developed Venetian relazione from the 16th century and later on in time was quite different from a final report on the procedures and outcome of a mission.

The Ottoman precedent for such activities is nowhere better demonstrated than in the relazioni that Venetian consuls routinely delivered before the Senate upon recall from postings in the Ottoman capital. The goal of these reports was to contain the Turkish advance and to defend Venetian positions.

- — Daniel Goffman, "Negotiating with the Renaissance State: The Ottoman Empire and the New Diplomacy"[3]

Relazioni gave Venetians the knowledge they needed to know about the enemy (the Ottomans). Relazioni were very significant to Venetians because they contained stress points and fault lines where the Ottoman Empire might weaken of its own account or where Venice might intervene. In simple terms they were significant to Venetians as they were like a "Strategy Guide" that the Venetians could turn to if they had to.

The popularity of Relazioni

In the course of the sixteenth century the fame of the Venetian relazioni spread far and wide and copies were sold abroad at good prices, not only to governments, but also to erudite collectors.

- — Donald E. Queller, "The Development of Ambassadorial Relazioni"[4]

Venetian noble families kept their own copies of relazioni, especially those families by which a member of the family had brought honour upon the house. From these sources came the copies that are now in various libraries and archives. In the 16th century gained international popularity and concern for the security of the relazioni grew. Unless there became a control over the distribution of relazioni, the Venetians feared, "the ill effect of either sealing their envoys' lips or divulging to the public what ought to be kept a secret."[5] Unfortunately for the Venetian government, the efforts to achieve security of the relazioni were never successful, however "it is the great good fortune of the modern historian, for to the scattered copies we owe many of the extant relazioni, especially the earliest."[6]

See also

Citations

- ↑ Goffman, Daniel (2007). "Negotiating with the Renaissance State: The Ottoman Empire and the New Diplomacy". In The Early Modern Ottomans: Remapping the Empire. Eds. Virginia Aksan and Daniel Goffman. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 62.

- ↑ Queller, Donald E. (1973). "The Development of Ambassadorial Relazioni". In Renaissance Venice. Ed. J. R. Hale. London: Faber and Faber, p. 175.

- ↑ Goffman, Daniel. 2007. "Negotiating with the Renaissance State: The Ottoman Empire and the New Diplomacy". In The Early Modern Ottomans: Remapping the Empire. Eds. Virginia Aksan and Daniel Goffman. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press p. 71

- ↑ Queller, Donald E. 1973. "The Development of Ambassadorial Relazioni". Renaissance Venice. Ed. J. R. Hale. London: Faber and Faber p. 176

- ↑ Queller, Donald E. 1973. "The Development of Ambassadorial Relazioni". Renaissance Venice. Ed. J. R. Hale. London: Faber and Faber p. 177

- ↑ Queller, Donald E. 1973. "The Development of Ambassadorial Relazioni". Renaissance Venice. Ed. J. R. Hale. London: Faber and Faber p. 177

General references

- Goffman, Daniel. 2007. "Negotiating with the Renaissance State: The Ottoman Empire and the New Diplomacy". The Early Modern Ottomans: Remapping the Empire. Eds. Virginia Aksan and Daniel Goffman. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press pp. 61–74

- Queller, Donald E. 1973. "The Development of Ambassadorial Relazioni". Renaissance Venice. Ed. J. R. Hale. London: Faber and Faber pp. 174–196.

Further reading

- Brummett, Palmira. 2007. "Imagining the Early Modern Ottoman Space, from World History to Piri Reis". The Early Modern Ottomans: Remapping the Empire. Eds. Virginia Aksan and Daniel Goffman. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press pp. 15–58

- Carman, Elizabeth. 1997. "Diplomacy Through the Grapevine: Time, Distance, and Sixteenth-Century Ambassadorial Dispatches". Ex Post Facto 6.

- de Wicquefort, Abraham (1716). The Embassador [sic] and His Functions To Which Is Added, an Historical Discourse, Concerning the Election of the Emperor and the Electors. Trans. John Digby. London: Printed for B. Lintott. pp. 253–256.