Republic of China 中華民國 Zhōnghuá Mínguó | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1912–1928 | |||||||||||||||||

| Anthem: Various

| |||||||||||||||||

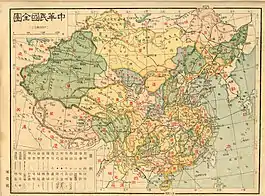

Republic of China between 1912 and 1928. | |||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Beijing 39°54′N 116°23′E / 39.900°N 116.383°E | ||||||||||||||||

| Largest city | Shanghai | ||||||||||||||||

| Official languages | Standard Chinese | ||||||||||||||||

| Government | Parliamentary republic (1912–14, 1916–23, 1924, 1926–27) Presidential republic (1914–16, 1923–24, 1924–26, 1927–28) under military dictatorship (1927–28) | ||||||||||||||||

| President | |||||||||||||||||

• 1912–1916 | Yuan Shikai (first) | ||||||||||||||||

• 1927–1928 | Zhang Zuolin (last)[note 1] | ||||||||||||||||

| Premier | |||||||||||||||||

• 1912 | Tang Shaoyi (first) | ||||||||||||||||

• 1927–1928 | Pan Fu (last) | ||||||||||||||||

| Legislature | National Assembly | ||||||||||||||||

| Senate | |||||||||||||||||

| House of Representative | |||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||

• Presidential inauguration of Yuan Shikai | 10 March 1912 | ||||||||||||||||

• Legislative Yuan opened meeting | 8 April 1913 | ||||||||||||||||

| 4 May 1919 | |||||||||||||||||

• Northern Expedition started | 9 July 1926 | ||||||||||||||||

| 4 June 1928 | |||||||||||||||||

| 29 December 1928 | |||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Chinese yuan | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

The Beiyang government[note 2] was the internationally recognized government of the Republic of China between 1912 and 1928, based in Beijing. It was dominated by the generals of the Beiyang Army, giving it its name.

Beiyang general Yuan Shikai gave Sun Yat-sen the military support he needed to overthrow the Qing dynasty and establish the Republic of China in 1912. Through his control of the army, Yuan was quickly able to dominate the new Republic.[1] Although the government and the state were nominally under civilian control through the Republic's constitution, the Yuan and his generals were effectively in charge of it. After Yuan's death in 1916, the army split into various warlord factions competing for power, leading to a period of civil war called the Warlord Era. Nevertheless, the government maintained its legitimacy among the great powers, receiving diplomatic recognition, foreign loans, and access to tax and customs revenue.

Its legitimacy was seriously challenged in 1917, by Sun Yat-sen's Canton-based Kuomintang (KMT) government movement. His successor Chiang Kai-shek defeated the Beiyang warlords during the Northern Expedition between 1926 and 1928, and overthrew the factions and the government, effectively unifying the country in 1928. The Kuomintang proceeded to install its nationalist government in Nanjing;[2] China's political order became a one-party state, and the Kuomintang government subsequently received international recognition as the legitimate government of China.

Political system

Under the Provisional Constitution of the Republic of China, as drawn up by the provisional senate in February 1912, the National Assembly (parliament) elected the president and vice president for five-year terms, and appointed a premier to choose and lead the cabinet.[3] The relevant ministers had to countersign executive decrees for them to be binding. The most important ministries were army, finance, communications, and interior. The navy ministry's importance declined significantly after most of its ships defected to the South's Constitutional Protection Movement in 1917. The communications ministry was also responsible for transportation, mail, and the Bank of Communications and was the base of the influential Communications Clique.[4] The interior ministry was responsible for policing and security while the weaker ministry of justice handled judicial affairs and prisons. The ministry of foreign affairs had a renowned diplomatic corps with figures such as Wellington Koo. Because the generals required their skills, the foreign affairs ministry was given substantial independence. The ministry's greatest accomplishment was the 1922 return of German concessions in Shandong that were seized by Japan during World War I, which greatly boosted the government's reputation. The foreign affairs ministry successfully denied the South's government of any international recognition all the way until the Beiyang government collapsed. China was a founding member of the League of Nations.

The assembly was bicameral with a senate that had six-year terms divided into two classes and a house of representatives with three-year terms. The senators were chosen by the provincial assemblies and the representatives were chosen by an electoral college picked by a limited public franchise. The task of the assembly was to write a permanent constitution, draft legislation, approve the budget and treaties, ratify the cabinet, and impeach corrupt officials. An independent judiciary with a supreme court was also provided. Early law codes were based on reforming the Great Qing Legal Code into something akin to German civil law.

In reality, these institutions were undermined by strong personal and factional ties. Overall, the government was extremely corrupt, incompetent, and tyrannical. Most of the revenue was spent on the military forces of whichever faction was currently in power. The short-lived legislatures did have civilian cliques and debates, but were subject to bribery, forced resignations, or dissolution altogether.

During the Warlord Era, the government remained very unstable, with seven heads of state, five caretaker administrations, 34 heads of government, 25 cabinets, five parliaments, and four charters within the span of twelve years. It was near bankruptcy several times where a mere million dollars could decide the fate of the bureaucracy. Its income came primarily from the customs revenue, foreign loans, and government bonds, as it had difficulty collecting taxes outside the capital even if the surrounding regions were controlled by allied warlords. After the 1920 Zhili–Anhui War, no taxes were remitted to Beijing other than Zhili province.

History

Background

The origins of the Beiyang government lie in the aftermath of the First Sino-Japanese War of 1895. The defeated armies of the Qing dynasty instituted a series of military reforms known as the New Army reforms, headed by general Li Hongzhang. Among the regional armies that emerged from these reforms was the Beiyang Army, named such due to being the army that served the Beiyang region. Commanded by general Yuan Shikai, the Beiyang Army grew to become the largest and most modernized of the New Armies. As a result, Yuan began to become a highly influential figure in the Qing government, and in 1907 was appointed to the high positions of Grand Councillor and Secretary of Foreign Affairs, which he held until being relieved of both positions by Imperial Regent Prince Chun in 1909.

Following the Wuchang Uprising in October 1911, after which the armies of the southern provinces rebelled against the Qing, Yuan Shikai was recalled to Beijing to command the Beiyang Army against the rebellion. The Qing became a constitutional monarchy, with Yuan Shikai holding the position of Prime Minister of the Imperial Cabinet. His cabinet was made up primarily of Han Chinese members, as opposed to Manchu who had traditionally comprised the Qing political elite. Fearing he would lose his administrative powers after his Beiyang Army suppressed the revolution, Yuan decided to come to a deal with the revolutionaries, and on 12 February 1912 he deposed the Xuantong Emperor, thus effectively abolishing the Qing dynasty.

Under Yuan Shikai (1912–1916)

After the Xinhai Revolution of 1911–1912, the rebels established a republican Provisional Government in Nanjing under President Sun Yat-sen and Vice President Li Yuanhong. Since they only controlled southern China, they had to negotiate with Yuan Shikai to put an end to the Qing dynasty. On 10 March 1912, Yuan became provisional president while located in Beijing, his power base. He refused to move to Nanjing, fearing further assassination attempts. It was also more economical to keep the existing Qing bureaucracy in Beijing, so the provisional senate moved north as well; the government thereby began its administration from Beijing on 10 October 1912.

The 1912–1913 National Assembly elections gave over half the seats and control of both houses to Sun's Nationalist Party (KMT). The second-largest party, the Progressives led by Liang Qichao, generally favored Yuan. Song Jiaoren was expected to become the next premier, but he riled Yuan by promising to pick a cabinet with only KMT ministers. He was assassinated less than two weeks before the assembly convened. An investigation pinned the blame on Premier Zhao Bingjun, which suggested Yuan had played a part. Yuan denied that either he or Zhao killed Song, but the Nationalists remained unconvinced. Yuan then took out a huge foreign loan without parliament's consent. Sun led a faction of Nationalists against Yuan in a Second Revolution during the summer of 1913 but suffered complete defeat within two months.

Revival of the monarchy

In response to threats and bribes, parliament elected Yuan for a five-year term beginning on 10 October 1913. He then expelled the Nationalist legislators causing the assembly to lose quorum which forced it to adjourn. In 1914, a Constitutional Conference rigged in his favor produced the Constitutional Compact, which gave the presidency sweeping powers. The new legislature, the National Council, had the power to impeach him but Yuan also had the power to dismiss it at whim before any proceedings could take place. Still not satisfied, he reasoned that the Chinese people were used to autocratic rule and that he should seek to install himself as a new emperor. Yuan furthermore began participating in old Confucian rites connected to the monarchy.

In 1915 Yuan crafted a monarchist movement which symbolically begged him to take to the throne. He would politely and humbly refuse each time until a special national convention of nearly two thousand delegates unanimously endorsed him. Yuan Shikai "reluctantly" accepted and was crowned Emperor of China.

Former Justice Minister Liang Qichao saw through the ruse and encouraged the Yunnan clique to rebel against Yuan, sparking the National Protection War. The war went badly for Yuan, as he faced almost universal opposition. Most of his lieutenants deserted him. In order to win them back he announced the end of the Empire of China on 22 March 1916. However, his enemies called for his resignation as president. In June, Yuan died of uremia, leaving a fractured republic in his wake.

The beginning of the Warlord Era (1916–1920)

Li Yuanhong succeeded Yuan as president on June 7. Due to his anti-monarchist stance in Nanjing, Feng Guozhang became vice president. Duan Qirui retained his position as premier. The original parliament elected in 1913 reconvened on August 1 and restored the provisional constitution. There were three factions in parliament now: Sun Yat-sen's Chinese Revolutionary Party, Liang Qichao's Constitution Research Clique, and Tang Hualong's Constitution Discussions Clique.

The first order of business was the creation of a national army. This was problematic as the southerners reacted suspiciously in fear that they may be deprived of their commands to untrustworthy Beiyang generals. No progress was made on this issue.

The second issue was World War I. Premier Duan and Liang Qichao was in favor of entering the war on the Allied side. President Li and Sun Yat-sen were opposed. Duan managed to strongarm parliament into breaking ties with the German Empire. Li fired Duan when his secret loans from Japan were revealed. Duan denounced his removal as illegal and set up base in Tianjin. Most of the Beiyang generals sided with Duan and demanded the dissolution of parliament. In June 1917, General Zhang Xun offered to mediate and went to Beijing with his soldiers. Backed with German funds and arms, he occupied the capital and forced Li to dissolve parliament. On July 1, he shocked the country by restoring Puyi as emperor.

After escaping to the Japanese legation, Li reappointed Duan Qirui as premier and charged him with protecting the republic. Duan led an army that quickly defeated the Manchu Restoration. Li resigned as president and was succeeded by Feng Guozhang. Duan refused to restore parliament due to his unpleasant experiences with it in the past. He argued that his victory over the Manchu Restoration counted as a second Xinhai Revolution and set out to craft a new provisional senate which will draft the election rules for a new parliament. This senate cut the number of seats in the future parliament by nearly half.

His opponents disagreed claiming that under Duan's argument, he should resign as the premier's position cannot exist independently from parliament. Sun Yat-sen and his followers moved to Guangzhou to set up a rival government under the Constitutional Protection Movement with the backing of the Yunnan clique and the Old Guangxi clique. A rump of the old parliament held an extraordinary session.

The Beiyang government declared war on the Central Powers in August 1917 and began sending labor battalions to France and a token force to Siberia. Duan took out large loans from Japan, claiming that he planned to build an army of a million men to send to Europe but his rivals knew this army would never leave the country: its true purpose was to crush internal dissent, since it existed outside the jurisdiction of the army ministry. Meanwhile, the war between the northern and southern governments led to a stalemate as neither side could defeat the other. Duan's favoritism in promoting relatives, friends, Anhuites, and proteges to high positions in the military and government caused strong divisions within the Beiyang army. His followers became known as the Anhui clique. His detractors rallied around President Feng and formed the Zhili clique. The Zhili clique favored peaceful negotiations with the south while Duan wanted to conquer it. Duan resigned as premier due to the president's interference but his underlings pressured Feng to restore him.

The 1918 elections for the new parliament were rigged to favor Duan's Anfu Club which took three-fourths of the seats. The rest went to Liang Shiyi's Communications Clique, Liang Qichao's Research Clique, or to independents. Because President Feng was simply finishing the five-year term Yuan began in 1913, he was obliged to resign in October. Duan replaced his archrival with Xu Shichang as president, the closest to a normal transfer of power in this government's history. Duan promised Feng's ally, Cao Kun, the vice presidency but the Communications Clique and the Research Clique opposed it after newspapers reported that Cao lavished enormous amounts of money on a prostitute. They also preferred to give it to a figure in the renegade South as a token of reconciliation. However, no southerner took up the offer and this left the vice presidency vacant. This set up an enmity between Cao Kun and Duan. When Feng relinquished the presidency, Duan resigned his premiership. Duan, however, remained the country's most powerful man through his network in the government and military. Convening on 12 August, the new parliament spent much of its time trying to draft a new constitution to replace the 1912 provisional one and engaged in polemics against the rump old parliament in the south.

.jpg.webp)

In the 1919 Paris Peace Conference, Duan's ally, Cao Rulin, promised Japan all of Germany's concessions in Shandong. This sparked the May Fourth Movement which seriously weakened the Anhui clique's hold in government. Though the First World War had ended, the army Duan had created to send to the trenches was not disbanded. Instead, it was given to his deputy Xu Shuzheng to invade Outer Mongolia. This soured relations with Zhang Zuolin of Manchuria's Fengtian clique who considered such a large army bordering his territory as a threat. The Zhili clique demanded more influence in the government but in December Feng Guozhang died leaving the group momentarily leaderless. Cao Kun and Wu Peifu emerged as the leaders of the Zhili clique and they issued circular telegrams denouncing the Anhui clique. Cao and Zhang pressured the president to dismiss Xu Shuzheng. The president was already leaning against Duan for sabotaging his Shanghai peace talks with the South in 1919. Both Xu and Duan denounced the dismissal and promptly declare war on 6 July 1920. On July 14, the two sides clashed in the Zhili–Anhui War. Within a few days, the Anhui clique was defeated and Duan retired from the military. The new parliament was dissolved on August 30.

Ascendancy of the Zhili clique (1920–1924)

Although Zhang Zuolin's Fengtian clique played a minor role assisting the Zhili clique in the war, they were allowed to share power in Beijing. Jin Yunpeng, who had ties to both sides, was chosen as premier. President Xu called for parliamentary elections in the summer of 1921 but because only 11 provinces took part the elections became invalid and no assembly was convened.

Zhang became worried over Wu Peifu's growing military strength and anti-Japanese stance which threatened his backers in Japan. Using a financial crisis as a pretext, he removed Jin and replaced him with Liang Shiyi in December 1921. Wu forced Liang to resign after a month accusing him of being pro-Japanese. He exposed Liang's telegram ordering diplomats to back Japan on the Shandong Problem during the Washington Naval Conference. Zhang then formed an alliance with the Duan Qirui and Sun Yatsen. Both sides sent circular telegrams to rally their officers and denounce their enemies. On April 28, the First Zhili–Fengtian War began with Wu clashed with Zhang's army in Shanhaiguan and won a major victory forcing Zhang to retreat to Manchuria.

Next, the Zhili clique started a national campaign to restore Li Yuanhong as president. Despite having co-existed with Xu Shichang for two years after the fall of Duan, they declared his presidency illegal as he was elected by an illegal parliament. They demanded Xu and Sun Yatsen resign their rival presidencies in favor of a unified government. Wu convinced Chen Jiongming to oust Sun from Guangzhou in return for recognition of his control over Guangdong. Enough members of the old parliament moved to Beijing to constitute a quorum which superficially gave the government an appearance that it operated as it did before the Manchu Restoration in 1917.

Li's new administration was more powerless than his first. His cabinet appointments had to be approved by Wu Peifu. Wu's growing power and prestige outshone his mentor and superior officer, Cao Kun, which strained relations between the two. Cao wanted to become president himself but Wu tried to restrain his ambitions. President Li tried to create an "Able Men Cabinet" consisting of experts but he ruined it by arresting Finance Minister Luo Wengan on spurious rumours supplied by the speakers of parliament. The cabinet resigned en-masse and Wu was no longer able to shield Li. Cao Kun's followers controlled the new cabinet and bribed parliament to impeach Li. Next, Cao orchestrated strikes by unpaid police and had the utilities for the presidential manor cut. Li tried to take the presidential seal with him but was intercepted.

Cao Kun spent the next few months promoting his presidency by openly offering five thousand dollars to any member of parliament willing to elect him. This created universal condemnation but he was nevertheless elected and was inaugurated on Double Ten Day, 1923 with a new constitution, the only formal constitution promulgated until 1947. He neglected his presidential duties and would rather meet with his officers than the cabinet. The vice presidency was again left vacant to entice Zhang Zuolin, Duan Qirui, or Lu Yongxiang but none wanted to associate with Cao's infamy.

In September 1924, the Zhili clique general and Jiangsu governor Qi Xieyuan demanded control of Shanghai, which belongs in his province, from Lu Yongxiang's Zhejiang the last province controlled by the Anhui clique. Fighting broke out between the two provinces with Qi quickly gaining ground. Sun Yatsen and Zhang Zuolin pledged to protect Zhejiang, sparking the Second Zhili–Fengtian War. Zhejiang fell and for the next two months Wu was gradually winning against Zhang.

In the early morning hours of October 23, General Feng Yuxiang betrayed the Zhili clique by pulling off the Beijing Coup. He put President Cao under house arrest. Wu reacted furiously at this betrayal by pulling his army from the front to rescue Cao. Zhang pursued and attacked Wu's rear, defeating him at Tianjin. Wu escaped to the Central Plains where Sun Chuanfang held the line against Zhang.

Provisional Executive Government (1924–1926)

On 2 November 1924, Huang Fu was made acting president after Feng Yuxiang's request. He declared Cao Kun's presidency illegal as it was obtained by bribery. Any member of parliament who voted for him was subject to arrest. The 1923 constitution was invalidated and replaced with "Regulations for the Provisional Government". Puyi was expelled from the Forbidden City and several other reforms were made. Zhang, a monarchist, objected to the expulsion and Huang's government. Feng and Zhang agreed to make Duan Qirui the head of the provisional government and permanently dissolve the old parliament. The Provisional Chief Executive had the combined powers of the president and premier, the ability to pick his cabinet freely, and could rule without a legislature. While theoretically very powerful, in reality, Duan was at the mercy of Feng and Zhang.

Feng, Zhang, and Duan invited Sun Yat-sen north to discuss national reunification. Sun travelled to Beijing but his liver cancer progressed. Duan created a 160-member Reconstruction Conference on 1 February. Sun was skeptical of Duan and Zhang who toyed with the idea of restoring Puyi. Sun died in March, leaving his southern followers divided.

Duan created a provisional legislature on July 30, the Beiyang government's last assembly. A constitutional drafting commission was also held from August to December but its draft was never accepted as warfare broke out after Fengtian clique general Guo Songling defected to Feng Yuxiang's Guominjun in November, sparking the Anti-Fengtian War. Wu Peifu made an alliance with Zhang against Feng in revenge for the coup. Guo was killed on December 24 and fighting went so badly against the Guominjun, Feng resigned and moved to the Soviet Union but was recalled by his officers in a few months. When the tide turned against the Guominjun, Duan restored the office of premier to shift responsibilities away from himself. The March 18 Massacre of protesters in Beijing led to Duan's downfall. Under heavy pressure, Duan held a special session of the provisional legislature that passed a resolution condemning the massacre. It did not stop Guominjun soldiers from disarming Duan's guards and forcing the Chief Executive to flee to a diplomatic legation the next month. When Zhang's troops retook the capital weeks later, he refused to restore Duan whom he saw as a treacherous double-dealing opportunist. The capital suffered heavily during the initial occupation as Zhang and Wu's troops raped and pillaged the city's inhabitants.

Zhang and Wu disagreed on who should succeed Duan. Wu wanted to restore Cao Kun as president but Zhang was vehemently opposed. What followed was a series of weak interim governments. The civil service collapsed due to the pillaging and lack of pay and the ministries existed in name only. There were mass resignations with remaining cabinet ministers pressured by the military to stay on. The only functioning parts of the bureaucracy were the postal service, customs revenue service, and the salt administration which was staffed by foreign employees. No legislature was created as it would have been too expensive and difficult to assemble.

Northern Expedition and military government (1926–1927)

In July 1926, the Kuomintang launched their Northern Expedition to reunify China and defeat the warlords. They rapidly defeated the armies of Beiyang-affiliated warlords Wu Peifu and Sun Chuanfang, sparking Zhang Zuolin to establish the National Pacification Army (NPA; also known as the Anguojun/Ankuochun) anti-Kuomintang warlord coalition in November 1926. Following a series of internal struggles within the KMT, Chiang Kai-shek purged the Communists from his National Revolutionary Army in April 1927, and the expedition was halted. During this period, a conference of the warlord leaders of the NPA was held in June 1927. They resolved that all civil and military power would be concentrated in the person of Zhang Zuolin.[5] Zhang was declared "Generalissimo", and consequently formed a new military government. This was the only time in the history of the Beiyang regime that it was explicitly a military government. Pan Fu was made Prime Minister and Minister of Communications, Liu Changqing was made Minister of Agriculture and Labor, Yan Zebo was made Minister of Finance, Wang Yingtai was made Minister of Foreign Affairs, Liu Zhe was made Minister of Education, He Fenglin was made Minister of Military Affairs (including the navy), Shen Ruilin was made Minister of the Interior, Zhang Jinghui was made Minister of Industry, Yao Zhen was made Minister of Justice, and Xia Renhu was made Chief Cabinet Secretary. Zhang published a manifesto for the new government, declaring that he would free China from Bolshevism (the "Reds") and chaos, and that he would reverse the unequal treaties through negotiation. Soon after, Zhang's Foreign Office sent a request to the Japanese Legation in China to request the withdrawal of Japanese troops from Shandong.[6] The civil service began to improve and start functioning again. The navy and army ministries were merged to create the Ministry of Military Affairs.

In early 1927, the NPA Political Commission, in an effort to make Zhang Zuolin seem more legitimate and popular, declared that a new policy would be taken by Zhang: "Development of the democratic spirit and opposition to oppression by force. Restoration of the national sovereignty and abolition of the "unequal treaties." Improvement of economic conditions and co-operation between capital and labor. Encouragement of popular education. Enforcement of a system of local self government. Reclamation of the frontiers and colonization of undeveloped areas. Preservation of the national sovereignty and characteristics. Readjustment of official morality and development of the morality of the people."[7]

Immediately following the defeat of Wu Peifu, the Fengtian clique and the KMT had to decide what to do with the political situation in Manchuria. In August 1926, Jiang Zuobin, a KMT general in Hubei, was sent from Guangzhou to Mukden to discuss a possible alliance. Towards Winter 1926–1927, foreign observers were predicting the possibility of a Fengtian–KMT settlement. On 14 January, Reuters reported that Yang Yuting was working with Liang Shiyi to draw up a compromise between the two governments.[8] During the early 1927 Fengtian–KMT negotiations, the KMT promised to "end the Northern Expedition (at Hubei, where they had already reached)", and allow the Fengtian clique to expand towards the south. According to the KMT, Zhang Zuolin would be made the Chair of the Central Executive Committee of the government according to the KMT, while Zhang himself wanted either himself or another Fengtian representative to be made President, with KMT representatives in the positions of Vice President and Premier. Zhang asked the KMT to stay to the provinces of Hunan, Hubei, Zhejiang, Sichuan, Yunnan, Guizhou, Guangdong and Guangxi, as well as ridding themselves of any foreign influence.[9]: 113

The military government was seen as something that could be redeemed from warlordism. There was a push for reform and reconstruction, as well as adopting a new modernity in politics.[9]: 128 Below is an extract from Dagongbao in August 1927, after the NPA defeated the Kuomintang in Xuzhou:

If [the North] could do what the KMT promulgates and shake off decadence and warlordism, [the KMT defeat in Xuzhou] might be the end of the KMT... Success and failure depend on one's action rather than the others’ failure...[9]: 128 [10]

However, the military government was never really able to establish its legitimacy well, as Zhang Zuolin lacked the political power to make reforms. Additionally, NPA military failures were detrimental to the public view of the NPA.[9]: 142

Demise (1928)

The National Pacification Army attempted to make other warlords, and, to some extent, ordinary people, perceive it as a peaceful unifying force, in contrast to the violent, revolutionary unification offered by the Kuomintang.[9]: 92 The militarists in the NPA tried to reach a compromise with moderates in the KMT, believing that they could unify the country without bloodshed. From March to August 1927, the Fengtian clique and the KMT entered into negotiations. However, the leaders of the KMT were determined to pursue the destruction of the Beijing Government, and in mid-1927, Feng Yuxiang's Guominjun and Yan Xishan's Shanxi army swore allegiance to Chiang's KMT government in Nanjing, dealing a substantial blow to the Beiyang government.[9]: 93

Following their retreat from Henan, NPA leaders (excluding Sun Chuanfang and Zhang Zongchang) came together on 7 June 1927. The generals agreed to try to seek rapprochement with Nanjing and to endorse the Three Principles of the People. They proposed a new principle of "morality" (Chinese: 民德; pinyin: míndé; Wade–Giles: min2-te2). They agreed on a reformation of the national government and suggested for Zhang a choice to either return to Manchuria and distance himself from politics or to establish his position as an important politician in the government. Two of the clauses agreed upon were the total destruction of Feng Yuxiang and joint decision-making in diplomacy between both the Beijing and Nanjing governments.[9]: 123

With the continuing advance of the KMT, Zhang was forced to abandon Beijing on June 3, 1928. On the way back to his power-base in Manchuria the next morning, his train was blown up by officers of the Japanese Kwantung Army, killing him, in what is known as the Huanggutun incident. Yan Xishan's troops soon occupied Beijing, effectively dissolving the Beiyang government; unification was declared on June 16 by the Nationalists.[11] Beijing was renamed Peiping until the end of the Chinese Civil War in 1949. Zhang's son, Zhang Xueliang, took over the National Pacification Army and retained a government in exile led by Premier Pan Fu. However, many civil servants, including former ministers and presidents, had already switched over to the Nationalist government. The United States became the first major power to switch recognition to the Nationalist government in Nanjing on October 1. Japan was the last major power to switch because they detested the anti-Japanese attitude of the KMT. Zhang negotiated with Chiang Kai-shek to end this pretense leading to the dissolution of the Beiyang government, the NPA, and the unification of China under the Nationalist flag on 29 December 1928.

Maps of China from 1911 to 1928

From 1911 to 1916.

From 1911 to 1916. From 1916 to 1920.

From 1916 to 1920. From 1921 to 1922.

From 1921 to 1922. From 1923 to 1924.

From 1923 to 1924. From 1925 to 1926.

From 1925 to 1926. From 1927 to 1928.

From 1927 to 1928.

Japanese attempts at revival

The Japanese had poor relations with the new KMT one-party state in Nanjing. When the Japanese created the separatist Manchukuo in 1932, the new country used Beiyang symbolism. These were followed by Mengjiang, the Provisional Government, and the Reformed Government; which all used Beiyang symbols. When the high ranking Nationalist Wang Jingwei defected to the Japanese, he was put in charge of the Reorganized Government in 1940. Wang insisted upon adopting Nationalist symbols to create a parallel rival government against the KMT government in Chongqing instead of reviving the Beiyang government. Both Wang's government and Chongqing's Nationalist government used near identical symbols and claimed their continuity from Sun Yat-sen's rather than Yuan Shikai's regime.

See also

Notes

References

- ↑ Gao, James Z. (2009). Historical dictionary of modern China (1800–1949). Lanham, Md.: Scarecrow Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-0810863088. OCLC 592756156.

- ↑ Wakabayashi, Bob Tadashi (2007). The Nanking atrocity, 1937–38 : complicating the picture. Wakabayashi, Bob Tadashi. New York: Berghahn Books. pp. 202. ISBN 978-1845451806. OCLC 76898087.

- ↑ Teon, Aris (2016-05-31). "Provisional Constitution of the Republic Of China (1931)". The Greater China Journal. Archived from the original on 2019-07-12. Retrieved 2019-03-14.

- ↑ Chung, Stephanie Po-Yin (1998). Chinese business groups in Hong Kong and political change in South China, 1900–25. New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 9. ISBN 0585032696. OCLC 43474551.

- ↑ The Week in China. 1927. p. 5. Archived from the original on 2023-04-13. Retrieved 2020-02-04.

- ↑ "Chang Tso-Lin's New Position." Advocate of Peace through Justice, vol. 89, no. 8, 1927, pp. 473–474. JSTOR 20661678. Accessed 4 Feb. 2020.

- ↑ “The Chinese Crisis.” Advocate of Peace through Justice, vol. 89, no. 4, 1927, pp. 211–212. JSTOR 20661555. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- ↑ Clarence Martin Wilbur; Julie Lien-ying How (1989). Missionaries of Revolution: Soviet Advisers and Nationalist China, 1920–1927. Harvard University Press. pp. 394–. ISBN 978-0-674-57652-0.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Chi Man Kwong (2017). War and Geopolitics in Interwar Manchuria: Zhang Zuolin and the Fengtian Clique during the Northern Expedition. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-34084-8. Archived from the original on 13 April 2023. Retrieved 5 February 2020.

- ↑ Guomindang zhi chengbai yu guomin yundong. DGB, 20 August 1927.

- ↑ "Nationalists Declare Their Aims for China; Nanking Statement Pledges End of Militarism and Asks Equality With Other States". The New York Times. June 17, 1928. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 24, 2021. Retrieved April 14, 2020.

Further reading

- William C. Kirby (2000). State and Economy in Republican China: A Handbook for Scholars, Vol. 2. Harvard University Asia Center. ISBN 978-0674003682.

- Christopher R. Lew; Edwin Pak-wah Leung (2013). Historical Dictionary of the Chinese Civil War. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0810878747.

.svg.png.webp)