| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

1,000 delegates to the 1940 Republican National Convention 501 (majority) votes needed to win | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

From March 12 to May 17, 1940, voters of the Republican Party chose delegates to nominate a candidate for president at the 1940 Republican National Convention. The nominee was selected at the convention in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania from June 24–28, 1940.[2]

The primaries were contested mainly by Manhattan District Attorney Thomas E. Dewey and Senators Robert A. Taft and Arthur Vandenberg, though only a few states' primaries featured two or more of these men.

By the start of the convention, only 300 of the 1,000 convention delegates had been pledged to a candidate, far fewer than was necessary to determine a victor. Estimates of delegate loyalty placed Dewey first, Taft second, and Wendell Willkie, an internationalist businessman, third.[1] Late momentum following the escalation of World War II allowed Willkie to take the nomination on the sixth ballot at the convention.

Background

1936 presidential election

In 1936, Democratic President Franklin D. Roosevelt defeated Alf Landon in a historic landslide; his party expanded its majority in both houses of Congress. The result left the Republican Party at its lowest point since its founding: diminished, leaderless, and unpopular. Following two successive landslide defeats, the party was bereft of potential candidates for President in 1940.

1938 midterms

In the wake of his historic victory, Roosevelt overplayed his hand. He attempted to expand his formal powers dramatically (as in the proposed Judicial Procedures Reform Bill and Reorganization Bill) and informally purge his party of its conservative elements, angering allies and the public. The country also suffered an economic recession, further damaging Roosevelt's popularity. The 1938 elections were thus a massive victory of the Republican Party. The results reinvigorated Republicans and halted the growth of Roosevelt's New Deal.

New York was a notable exception to the Republican gains. Young prosecutor Thomas E. Dewey had made a national name for himself as a "Gangbuster" after his convictions of numerous American Mafia figures, including Lucky Luciano and Waxey Gordon. However, in one of the most watched races of the year, he narrowly failed to unseat Governor Herbert Lehman.

Dewey had made major improvements on the disastrous performance of Robert Moses in the 1936 race and elevated his status to that of a national politician. William Allen White compared his loss favorably to that of Abraham Lincoln in 1858: a prelude to the presidency. A poll by Gallup, Inc. shortly after his loss showed Dewey as the leading Republican candidate for the presidency with 33 percent of the popular vote.[3]

Pre-campaign maneuvering

.jpg.webp)

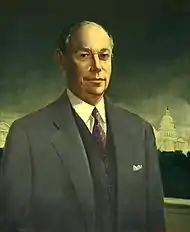

As the presidential field shaped up, Republican candidates were largely focused on opposition to President Roosevelt's involvement in European affairs. Among the leaders in their cause was Robert A. Taft, the newly elected Senator from Ohio and the son of a former president himself. Though Taft struggled to develop a popular following equal to that of Dewey's, he was positioned as a natural heir to his father's conservative, Midwestern base. Arriving in Washington as a young member of a party lacking in leaders, Taft was immediately lauded as a presidential contender.[4]

Meanwhile, Dewey set to work expanding and strengthening the New York Republican Party and continued in his role as Manhattan District Attorney.[4] His conviction of Tammany Hall leader James Joseph Hines won him further national praise, especially from Republicans eager to tie Hines to the Roosevelt administration. A Gallup poll following the verdict showed him with a majority of the Republican vote (well ahead of Taft and Senator Arthur Vandenberg) and leading President Roosevelt, 58–42.[5] In December, he delivered an anti-New Deal speech to a capacity crowd in Minneapolis.[6]

As Dewey resolved to seek the presidency, he made overtures to the conservative wing of the national party, including former President Herbert Hoover. These efforts simultaneously alienated New York County party chair Kenneth F. Simpson, an avowed liberal Dewey ally and Hoover critic; instead of supporting Dewey's campaign, Simpson joined with Russell Davenport to support a Democratic businessman for the nomination: Wendell Willkie, president of a utilities holding company and an eloquent critic of the New Deal.[7]

From the start, Dewey engaged in a popular campaign designed to secure the nomination through a show of overwhelming support in the primary elections, whereas Taft and Vandenberg (who avoided making any formal commitment to running) pursued victory through the backroom convention and caucus processes.[8]

Candidates

The following political leaders were candidates for the 1940 Republican presidential nomination:

Major candidates

These candidates participated in multiple state primaries or were included in multiple major national polls.

Competing in primaries

| Candidate | Most recent position | Home state | Campaign | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thomas E. Dewey |  |

Manhattan District Attorney (1938–41) |

New York |

(Campaign) | |

| Robert A. Taft |  |

U.S. Senator from Ohio (1939–53) |

Ohio |

(Campaign) | |

| Arthur Vandenberg |  |

U.S. Senator from Michigan (1928–51) |

Michigan |

||

Bypassing primaries

The following candidates did not actively campaign for any state's presidential primary, but may have had their name placed on the ballot by supporters or may have sought to influence to selection of un-elected delegates or sought the support of uncommitted delegates.

| Candidate | Most recent position | Home state | Campaign | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Styles Bridges |  |

Senator from New Hampshire (1937–61) |

New Hampshire |

|

| Herbert Hoover |  |

President of the United States (1929–33) |

|

(Campaign) |

| Arthur James | .jpg.webp) |

Governor of Pennsylvania (1939–43) |

Pennsylvania |

|

| Frank Gannett |  |

Newspaper publisher |  New York |

|

| Wendell Willkie |  |

Businessman |  New York |

(Campaign) |

Favorite sons

The following candidates ran only in their home state's primary or caucus for the purpose of controlling its delegate slate at the convention and did not appear to be considered national candidates by the media.

- Governor Harland Bushfield of South Dakota

- Senator Arthur Capper of Kansas

- Ryan N. Davis of West Virginia

- House Minority Leader Joseph W. Martin of Massachusetts

- Governor Harold E. Stassen of Minnesota

- Senate Minority Leader Charles L. McNary of Oregon

- Charles Montgomery of Ohio

- State Senator Jerrold L. Seawell of California

Declined to run

The following persons were listed in a major national poll or were the subject of media speculation surrounding their potential candidacy, but declined to actively seek the nomination.

- Governor George Aiken of Vermont (ran for U.S. Senate)

- Representative Bruce Barton of New York (ran for U.S. Senate) (endorsed Willkie)

- Senator William Borah of Idaho (died January 19, 1940)

- Governor John W. Bricker of Ohio

- Representative Hamilton Fish III of New York (withdrew from consideration February 25, 1940)

- Businessman Henry Ford of Michigan

- Former University President Glenn Frank of Wisconsin (ran for U.S. Senate and died September 15, 1940)

- Mayor Fiorello La Guardia of New York (endorsed President Roosevelt)[9]

- Former Governor Alf Landon of Kansas

- Aviator Charles Lindbergh of New Jersey

- Senator Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. of Massachusetts

- Senator Hiram Johnson of California

- Publisher Frank Knox (appointed as Secretary of the Navy on July 11, 1940)

- Theodore Roosevelt Jr. of New York

- Mayor Pratt C. Remmel of Little Rock, Arkansas

- Governor William Henry Vanderbilt III of Rhode Island (endorsed Willkie)[10]

- Representative James W. Wadsworth Jr. of New York

Polling

National polling

| Source | Publication | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gallup[11] | May 21, 1938 | ? | ? | – | 35% | – | ?[lower-alpha 2] |

| Gallup[12] | Nov. 27, 1938 | 33% | 6% | 18% | 18% | – | 25%[lower-alpha 3][lower-alpha 4] |

| Gallup[13] | Feb. 17, 1939 | 27% | 4% | 16% | 21% | – | 32%[lower-alpha 5][lower-alpha 6] |

| Gallup[14] | Mar. 22, 1939 | 50% | 5% | 13% | 15% | – | 23%[lower-alpha 7][lower-alpha 8] |

| Gallup[15] | May 10, 1939 | 54% | 4% | 15% | 13% | – | 14%[lower-alpha 9] |

| Gallup[16] | July 8, 1939 | 47% | 6% | 13% | 19% | – | 15%[lower-alpha 10] |

| Gallup[17] | Aug. 13, 1939 | 45% | 6% | 14% | 25% | – | 10%[lower-alpha 11] |

| Gallup[18] | Oct. 13, 1939 | 39% | 5% | 17% | 27% | – | 12%[lower-alpha 12] |

| Gallup[19] | Nov. 10, 1939 | 39% | 5% | 18% | 26% | – | 12%[lower-alpha 13][lower-alpha 14] |

| 44% | – | 25% | 31% | – | – | ||

| Gallup[20] | Jan. 7, 1940 | 60% | 5% | 11% | 16% | – | 8%[lower-alpha 15] |

| Gallup[21][22] | Feb. 1940 | 56% | 3% | 17% | 17% | – | 7%[lower-alpha 16] |

| 35% | 2% | 11% | 11% | – | 41%[lower-alpha 17] | ||

| Gallup[22] | Mar. 24, 1940 | 53% | 5% | 17% | 19% | – | 6%[lower-alpha 18] |

| 32% | 3% | 10% | 11% | – | 44%[lower-alpha 19] | ||

| Gallup[23][24] | May 8, 1940 | 67% | 2% | 12% | 14% | 3% | 2%[lower-alpha 20] |

| Gallup[24] | May 17, 1940 | 62% | 2% | 14% | 13% | 5% | 4%[lower-alpha 21] |

| Gallup | May 1940 | 56% | 2% | 16% | 12% | 10% | |

| Gallup[25] | June 12, 1940 | 52% | 2% | 13% | 12% | 17% | 4%[lower-alpha 22] |

| Gallup[25] | June 21, 1940 | 47% | 6% | 8% | 8% | 29% | 2%[lower-alpha 23] |

- ↑ Favorite sons received the majority of delegates from Pennsylvania (Arthur James), Oregon (Charles McNary), Kansas (Arthur Capper), and South Dakota, respectively. Publisher Frank Gannett received the majority vote of Arizona and Herbert Hoover tied for a plurality in California.

- ↑ Others mentioned but not counted included Thomas Dewey, Henry Cabot Lodge, Alf Landon, Herbert Hoover, and Glenn Frank.

- ↑ Alf Landon with 6%, Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. with 5%, and Arthur James with 2%

- ↑ Others mentioned but not counted included William Borah, Bruce Barton, and John Bricker.

- ↑ Alf Landon with 7%, William Borah with 4%, and Fiorello LaGuardia with 4%

- ↑ Other mentioned but not counted included Frank Knox, Henry Cabot Lodge, Arthur James, Bruce Barton, John Bricker, Leverett Saltonstall, George Aiken, James J. Wadsworth, Theodore Roosevelt Jr., Henry Ford, Harold Stassen, Arthur Capper, Julius Heil, Frank Gannett, Gerald Nye, and Hamilton Fish

- ↑ Alf Landon with 4% and William Borah with 2%

- ↑ Others named but not counted included Frank Knox, Hiram Johnson, Gerald Nye, George Aiken, Bruce Barton, Arthur James, Leverett Saltonstall, John Bricker, Fiorello LaGuardia, Theodore Roosevelt Jr., Frank Gannett, and Arthur Capper

- ↑ William Borah with 3%, Alf Landon with 3%, John Bricker with 1%, Henry Cabot Lodge with 1%, Fiorello LaGuardia with 1%, Bruce Barton with 1%, "All Others" with 4%

- ↑ Alf Landon with 4%, William Borah with 3%, Fiorello LaGuardia with 2%, Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. with 1%, John Bricker with 1%, and "All Others" with 4%

- ↑ Alf Landon with 3%, William Borah with 2%, John Bricker with 2%, and Others with 3%

- ↑ Alf Landon with 3%, William Borah with 3%, Charles Lindbergh with 1%, Henry Cabot Lodge with 1%, and Others with 4%

- ↑ Alf Landon with 3%, William Borah with 3%, Charles Lindbergh with 1%, Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. with 1%, and Others with 4%

- ↑ Among "Others", those receiving most frequent mention included Styles Bridges, Leverett Saltonstall, and William Vanderbilt.

- ↑ Arthur James with 1%, Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. with 1%, John Bricker with 1%, William Borah with 1%, Alf Landon with 1% and All others with 3%

- ↑ Frank Gannett with 1% and all others with 6%

- ↑ Frank Gannett with 1% and all others with 4%. 36% were undecided.

- ↑ Frank Gannet with 1%, Arthur James with 1%, and all others with 4%

- ↑ Frank Gannett with 1%, Arthur James with 1%, and all others with 2%. 40% were undecided.

- ↑ Others with 2%

- ↑ Frank Gannett with 1%, Styles Bridges with 1%, and Others with 2%

- ↑ Alf Landon with 1%, Frank Gannett with 1%, and Others with 2%

- ↑ Others with 2%

State polling

Illinois

| Source | Publication | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gallup[26] | Aug. 2, 1939 | 45% | 8% | 12% | 14% | – | 21%[lower-alpha 1] |

Massachusetts

| Source | Publication | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gallup[27] | Aug. 14, 1939 | 45% | 8% | 12% | 14% | – | 21%[lower-alpha 2] |

Michigan

| Source | Publication | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gallup[28] | Aug. 15, 1939 | 29% | 1% | 5% | 62% | – | 3%[lower-alpha 3] |

Ohio

| Source | Publication | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gallup[29] | Aug. 7, 1939 | 29% | 3% | 33% | 19% | – | 16%[lower-alpha 4] |

Wisconsin

| Source | Publication | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gallup | Aug. 15, 1939 | 37% | 5% | 16% | 24% | – | 18%[lower-alpha 5] |

Statewide contests

March 12: New Hampshire

The New Hampshire primary was the first in the nation and widely considered one of the most notable at the outset of the process. The state elected four delegates at-large and two from each of the state's two congressional districts.[30]

Though all delegates were formally uncommitted, J. Howard Gile of Nashua announced his intention to vote for Thomas Dewey — against the Dewey campaign's wishes. The Dewey campaign asked Gile to withdraw from the race; it was assumed Dewey had bypassed New Hampshire in respect and recognition of favorite-son presidential candidate Senator Styles Bridges, who ran as a delegate at-large.[30]

In the Second Congressional District, James P. Richardson expressed his support of Dewey but did not formally pledge himself to any candidate. Most of the elected delegates expressed a non-binding preference for Senator Bridges.

April 2: Wisconsin

The first competitive race was between Dewey and Vandenberg in Wisconsin. The state was expected to be favorable to Vandenberg, the Senator from neighboring Michigan. Vandenberg was also an opponent of expanded trade agreements, a supporter of dairy and beet farmers, an isolationist, and a supporter of the St. Lawrence Waterway project — all positions expected to gain him strong support in the state. It was also said that Vandenberg had the stronger, more popular slate of delegates.[31] He was also seen to have the support of the state's many Progressive Party voters as against Dewey, but may have been hurt by those voters' last-second swing to support President Roosevelt in the Democratic primary.[32]

Dewey gained support from voters and political leaders by announcing his support for the expansion of the St. Lawrence Waterway. After his endorsement, many of the state's Congressmen opted not to take sides in the race. Dewey also took a hit when the leadership of the state's active Progressive Party objected to a Dewey supporter's use of "Progressive" in campaign material.[31]

Dewey, unlike Vandenberg, personally campaigned in Wisconsin. He held a barnstorming tour across the state in the final week of March.[32] Although internal polling showed him winning easily, the Dewey campaign took an intentionally modest stance, expressing worry over the result and offering to split the delegation with Vandenberg.[33]

Although Wisconsin held a delegate election and a preference poll on primary day, Dewey's name was not entered the latter; his campaign opted only to run a slate of delegates.[32] His slate won 61.8% of the vote, carried all but four of Wisconsin's counties, and swept its 24 delegates.[33]

April 9: Illinois and Nebraska

The Illinois primary was initially expected to be one of the more competitive votes of the process. Congressman Hamilton Fish III filed to run as an isolationist candidate, but later withdrew his name.[34][35] Mayor of New York Fiorello La Guardia was also submitted as a candidate without his knowledge, but did not sign a statement of candidacy necessary to appear on the ballot and declined to be considered.[9][34] Regardless of who else appeared on the ballot, Dewey was considered the heavy favorite; he ultimately went unopposed. None of the state's delegates, who were elected separately, were bound by the "advisory" result.

Instead, most focus was on Nebraska, where Vandenberg made his last stand against Dewey. With the support of the party's Old Guard, including fellow Senators Arthur Capper, Charles McNary and Gerald Nye, the Vandenberg campaign argued that Dewey was unsound on agricultural issues. The campaign was in vain; Dewey won the state as easily as he had Wisconsin, effectively eliminating Vandenberg from contention. Sensing Dewey's popular momentum, Senator Taft withdrew from the Maryland and New Jersey primaries rather than face a likely popular defeat.[33]

| Date | Primary | Dewey | Vandenberg |

|---|---|---|---|

| April 9 | Illinois | 100% | – |

| Nebraska | 59% | 41% | |

April 23: Pennsylvania

| Date | Primary | Thomas Dewey | Arthur James | Robert A. Taft | Arthur Vandenberg | Wendell Willkie | Herbert Hoover | Unpledged |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| April 23 | Pennsylvania | 67% | 10% | 7% | 3% | 1% | 1% | 0% |

April: Massachusetts and Pennsylvania

In Massachusetts, all delegates were as a rule formally uncommitted, but could pledge themselves to a candidate if they wished. In general, the division was not based on any presidential candidacy but was between an establishment Republican slate and an insurgent Townsendite slate supporting the institution of an old-age pension.[36] Two delegates from Springfield, Dudley Wallace and Clarence Brooks, attempted to pledge themselves to Dewey but were not granted the privilege.[36]

The establishment slate listed as delegates at-large Governor Leverett Saltonstall, Senator Henry Cabot Lodge Jr., U.S. House Minority Leader Joseph W. Martin Jr., and State Treasurer John W. Haigis. The insurgent slate listed William McMasters, Byron P. Hayden, Harry P. Gibbs, and Seldon G. Hill.[36]

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Leverett Saltonstall | 62,152 | 22.11% | |

| Republican | Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr. | 61,539 | 21.89% | |

| Republican | John W. Haigis | 55,379 | 19.51% | |

| Republican | Joseph W. Martin Jr. | 54,845 | 19.51% | |

| Republican | William McMasters | 14,091 | 5.01% | |

| Republican | Byron P. Hayden | 11,489 | 4.09% | |

| Republican | Henry P. Gibbs | 10,845 | 3.86% | |

| Republican | Selden G. Hill | 10,756 | 3.83% | |

| Total votes | 281,117 | 100.00% | ||

May: War and momentum for Willkie

The May primaries largely went for local favorites. Dewey's name was entered in only three: New Jersey and Maryland, where he was unopposed, and Oregon, where he was soundly beaten as a write-in candidate in favor of Senator Charles McNary. However, Wendell Willkie received a strong 5.55% of the vote as a write-in candidate in New Jersey.

In May, Germany invaded the Low Countries and France in a major escalation of World War II. The events shook the primary race by ensuring the re-enlistment of President Roosevelt as a candidate for re-election to an unprecedented third term and refocusing the election on foreign policy. Dewey, until then the favorite for the nomination, began to struggle as he attempted to chart an inconsistent path between Vandenberg's isolationism and Roosevelt's aggressive involvement. Advised by John Foster Dulles, he was convinced that American involvement was unnecessary or futile.[37]

On May 10, the night of the invasion of the Netherlands, Ed Jaeckle privately told the Dewey campaign that his chances of being nominated were slim, but he should continue through the convention to ensure control of the New York party and his election as governor in 1942.[37] Taft and Dewey began to diverge on their attacks against the Roosevelt administration; Taft maintained strict opposition to American involvement in the war, while Dewey accepted American support for the Allies as inevitable and criticized the President's failure to ensure military preparedness in case of German aggression.[37]

The political benefits of the invasion went to Wendell Willkie over the two young favorites; an independent petition drive to nominate the businessman, led by Oren Root, gathered 4.5 million signatures. Willkie, who Alice Roosevelt Longworth has derided as having grassroots support "in every country club in America," began to attract popular audiences, and Willkie for President clubs sprouted across the country.

Post-primary events and Convention

By mid-June, little over one week before the Republican Convention opened, the Gallup poll reported that Willkie had moved into second place with 17%, and that Dewey was slipping. Fueled by his favorable media attention, Willkie's pro-British statements won over many of the delegates. As the delegates were arriving in Philadelphia, Gallup reported that Willkie had surged to 29%, Dewey had slipped 5 more points to 47%, and Taft, Vandenberg and former President Herbert Hoover trailed at 8%, 8%, and 6% respectively. Hundreds of thousands, perhaps as many as one million, telegrams urging support for Willkie poured in, many from "Willkie Clubs" that had sprung up across the country. Millions more signed petitions circulating everywhere.

At the 1940 Republican National Convention itself, keynote speaker Harold Stassen, the Governor of Minnesota, announced his support for Willkie and became his official floor manager. Hundreds of vocal Willkie supporters packed the upper galleries of the convention hall. Willkie's amateur status, his fresh face, appealed to delegates as well as voters. The delegations were selected not by primaries but by party leaders in each state, and they had a keen sense of the fast-changing pulse of public opinion. Gallup found the same thing in polling data not reported until after the convention: Willkie had moved ahead among Republican voters by 44% to only 29% for the collapsing Dewey. As the pro-Willkie galleries repeatedly yelled "We Want Willkie", the delegates on the convention floor began their vote. Dewey led on the first ballot but steadily lost strength thereafter. Both Taft and Willkie gained in strength on each ballot, and by the fourth ballot it was obvious that either Willkie or Taft would be the nominee. The key moments came when the delegations of large states such as Michigan, Pennsylvania, and New York left Dewey and Vandenberg and switched to Willkie, giving him the victory on the sixth ballot. The voting went like this:

| ballot: | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thomas E. Dewey | 360 | 338 | 315 | 250 | 57 | 11 |

| Ohio Senator Robert A. Taft | 189 | 203 | 212 | 254 | 377 | 310 |

| Wendell L. Willkie | 105 | 171 | 259 | 306 | 429 | 633 |

| Michigan Senator Arthur Vandenberg | 76 | 73 | 72 | 61 | 42 | - |

| Pennsylvania Governor Arthur H. James | 74 | 66 | 59 | 56 | 59 | 1 |

| Massachusetts Rep. Joseph W. Martin | 44 | 26 | - | - | - | - |

| Hanford MacNider | 32 | 34 | 28 | 26 | 4 | 2 |

| Frank E. Gannett | 33 | 30 | 11 | 9 | 1 | 1 |

| New Hampshire Senator Styles Bridges | 19 | 9 | 1 | 1 | - | - |

| Former President Herbert Hoover | 17 | - | - | - | 20 | 9 |

| Oregon Senator Charles L. McNary | 3 | 10 | 10 | 8 | 9 | - |

Willkie's nomination is still considered by most historians to have been one of the most dramatic moments in any political convention. Having given little thought to who he would select as his vice-presidential nominee, Willkie left the decision to convention chairman and Massachusetts Congressman Joe Martin, the House Minority Leader, who suggested Senate Minority Leader Charles L. McNary of Oregon. Despite the fact that McNary had spearheaded a "Stop Willkie" campaign late in the balloting, the candidate picked him to be his running mate.

| Charles L. McNary | 848 |

| Dewey Short | 108 |

| Styles Bridges | 2 |

See also

Notes

- ↑ Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. with 14%, Al Landon with 2%, Styles Bridges with 2%, and Others with 3%

- ↑ Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. with 14%, Al Landon with 2%, Styles Bridges with 2%, and Others with 3%

- ↑ Alf Landon with 2% and Others with 1%

- ↑ John Bricker with 12%, Alf Landon with 1%, and Others with 3%

- ↑ Fiorello LaGuardia with 4% and "Others" with 14% (including William Borah, Alf Landon, Henry Cabot Lodge Jr., and Styles Bridges)

References

- 1 2 3 4 "Willkie Reported "Practical" on G.O.P. Patronage". Cincinnati Enquirer. 24 Jun 1940. Retrieved 17 Dec 2022.

- ↑ Kalb, Deborah (2016-02-19). Guide to U.S. Elections - Google Books. ISBN 9781483380353. Retrieved 2016-02-19.

- ↑ Smith 1982, pp. 270–74.

- 1 2 Smith 1982, pp. 278–82.

- ↑ Smith 1982, p. 285.

- ↑ Smith 1982, p. 288.

- ↑ Smith 1982, pp. 292–93.

- ↑ Smith 1982, p. 297.

- 1 2 "La Guardia Drops Out of Illinois Primary; 'Phooey!' He Says of Republican Aspirants". The New York Times. 24 Feb 1940. p. 1.

- ↑ "VANDERBILT BACKS WILLKIE CANDIDACY". The New York Times. 16 June 1940. p. 20.

- ↑ Gallup, George (22 May 1938). "Vandenberg Holds G.O.P. Preference". Los Angeles Times. p. A5.

- ↑ Gallup, George (27 Nov 1938). "Rank and File Of Republicans Want New Faces Survey Shows". The Baltimore Sun. p. SM1.

- ↑ Gallup, George (17 Feb 1939). "Dewey, Vandenberg and Taft Lead in Gallup G. O. P. Poll". The Boston Daily Globe. p. 17.

- ↑ Gallup, George (22 Mar 1939). "Dewey Popularity For 1940 Boosted By Hines Conviction". The Baltimore Sun. p. 13.

- ↑ Gallup, George (10 May 1939). "Dewey and Taft Gain in Republican Popularity". Los Angeles Times. p. 26.

- ↑ "Vandenberg Gains in Voters' Survey". The New York Times. 8 Jul 1939. p. 2.

- ↑ Gallup, George (13 Aug 1939). "Vandenberg's Popularity Rises Sharply, Survey Of Republican Voters Shows". The Atlanta Constitution. p. 15A.

- ↑ Gallup, George (13 Oct 1939). "Dewey Maintains Lead in G.O.P. But Drops in Popularity Since War Began". The Washington Post. p. 2.

- ↑ Gallup, George (10 Nov 1939). "Dewey Holds 1940 Lead in Survey of Republicans". The Daily Boston Globe. p. 17.

- ↑ Gallup, George (7 Jan 1940). "Dewey Increases His Lead for Republican Nomination". Daily Boston Globe. p. 26.

- ↑ Gallup, George (11 Feb 1940). "Taft, Vandenberg Gain in Survey Of G. O. P. Voters But Dewey Leads". The Atlanta Constitution. p. 12A.

- 1 2 Gallup, George (24 Mar 1940). "Dewey vs. Vandenberg Test Indicates Close Contests". Los Angeles Times. p. A5.

- ↑ "POPULARITY GAIN SHOWN BY WILLKIE: 'DarkHorse' Has Jumped Ahead of Hoover and Landon". The New York Times. 8 May 1940. p. 18.

- 1 2 "WILLKIE IS CALLED CHIEF 'DARK HORSE': He Has 'Jumped From Nowhere to 4th Place in List'". The New York Times. 17 May 1940. p. 15.

- 1 2 Gallup, George (21 June 1940). "Dewey and Willkie Lead on Convention's Eve". Daily Boston Globe. p. 28.

- ↑ Gallup, George (2 Aug 1939). "Illinois Swing to G.O.P. Shown by Gallup Survey: Prairie State, Along With New York and Pennsylvania, Drifting From Democratic Fold". Los Angeles Times. p. 4.

- ↑ "Voters In Massachusetts Still Favor G. O. P.; Dewey, Garner Preferred for 1940". The Atlanta Constitution. 14 Aug 1939. p. 7.

- ↑ "Michigan Leans to G. O. P,; Vandenberg Leads Dewey, Popularity Survey Shows". The Atlanta Constitution. 9 Aug 1939. p. 4.

- ↑ "Ohio, One of Key States, Favors Return to Fold Of G.O.P. Survey Shows". The Atlanta Constitution. 7 Aug 1939. p. 8.

- 1 2 "Presidential Tests at Polls Open Tuesday: New Hampshire's Voters Will Have Opportunity to Support a DeweyMan Gamer and Farley Candidates Also Up 1936 Delegation Head, Pledged to Roosevelt, Excluded From Slate". The New York Herald Tribune. 10 Mar 1940. p. A1.

- 1 2 Blair, Edson (1 Apr 1940). "Washington: Both Sides of the Curtain ..: Much at Stake for Both Dewey and Vandenberg in This Week's Wisconsin Primary". Barron's. p. 4.

- 1 2 3 Fleming, Dewey (2 Apr 1940). "La Follettes Drifting Back To Roosevelt Band Wagon: Most Progressives Expected To Support President Today". The Baltimore Sun. p. 1.

- 1 2 3 Smith 1982, p. 301.

- 1 2 "LaGuardia's Name Filed in Illinois Race: Entered as a Republican Presidential Candidate, Says He Didn't Know It Garner Files to Run Against Roosevelt Hamilton Fish Is Placed on Ballot to Compete With Mayor and Dewey". New York Herald Tribune. 10 Feb 1940. p. 1.

- ↑ "Dewey Left Unopposed For Primary in Illinois: Fish's Withdrawal Follows Action by LaGuardia". The New York Herald Tribune. 25 Feb 1940. p. 6.

- 1 2 3 Hagerty, James (14 Mar 1940). "G.O.P. Regulars Face Contests Pledges Not Binding". The New York Times. p. 18.

- 1 2 3 Smith 1982, pp. 303–306.

Further reading

- Smith, Richard Norton (1982). Thomas Dewey and His Times. ISBN 9780671417413.

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)