| National TB Elimination Program (NTEP) | |

|---|---|

| Country | India |

| Launched | 1997 |

| Website | tbcindia Project Monitoring Portal |

The National Tuberculosis Elimination Programme (NTEP), earlier known as the Revised National Tuberculosis Control Programme (RNTCP), is the Public Health initiative of the Government of India that organizes its anti-Tuberculosis efforts. It functions as a flagship component of the National Health Mission (NHM) and provides technical and managerial leadership to anti-tuberculosis activities in the country. As per the National Strategic Plan 2017–25, the program has a vision of achieving a "TB free India",with a strategies under the broad themes of "Prevent, Detect,Treat and Build pillars for universal coverage and social protection".[1] The program provides, various free of cost, quality tuberculosis diagnosis and treatment services across the country through the government health system.

Program Structure

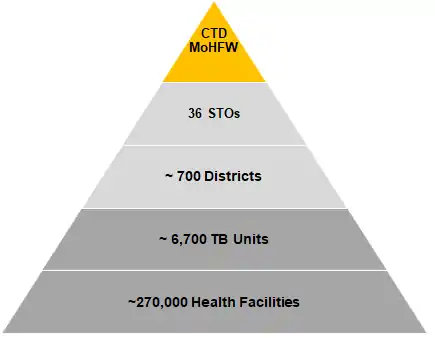

The program is managed through a four level hierarchy from the national level down to the sub-district (Tuberculosis Unit) level. At the country level the program is led by the Central TB Division under the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. The State TB Cell and the District TB Office govern the activities of the program at the state and district level respectively. At the sub-district/ Block level activities are organized under the Tuberculosis Unit (TB Unit). The Central TB Division is headed by a Deputy Director General - TB (DDG-TB) and is the National Program Manager. The administrative command falls to the Additional Secretary and Director General (NTEP and NACO) and the Joint Secretary-TB. Under the Central TB Division, a number of National Level Expert Committees and National Institutes for Tuberculosis, advise and assist in various programmatic functions. At the State level, a State TB Officer and at District level a District TB Officer manages the program.[2]

Laboratory Services

Diagnostic services under the program are provided through a network of various types of laboratories operating in a three tier fashion. At the service/ facility level there are microscopy and rapid molecular tests, constituting the first tier. The second tier is constituted by Intermediate Reference Laboratories(IRL) and Culture and Drug Susceptibility Testing (C&DST) Labs, which provide advanced DST facilities and supervisory support to the first tier. The National Reference Laboratories constitute the third tier, and provide quality assurance and certification services for C&DST labs and co-ordinate with WHO Supra National Reference Laboratory Network.[3] In addition to the above, Chest Radiography, available at tertiary and secondary healthcare levels, also play an important role in screening for Tuberculosis signs and clinical diagnosis.[4]

Designated Microscopy Centers (DMC)

Sputum smear microscopy, using the Ziehl–Neelsen staining technique, is conducted at the DMCs. This is the most widely available test with over 20,000 quality controlled laboratories across India. For diagnosis, two sputum samples are collected over two days (as spot-morning/morning-spot) from chest symptomatic (patients with presenting with a history of cough for two weeks or more) to arrive at a diagnosis. In addition to the test's high specificity, the use of two samples ensures that the diagnostic procedure has a high (>99%) test sensitivity as well.

Rapid Molecular Testing Labs

Cartridge Based Nucleic Acid Amplification Test (CBNAAT) using the GeneXpert Platform, and TruNat are rapid molecular tests for TB diagnosis and Rifampicin resistance detection . This test is the first choice of diagnostic test for high risk population, children, contacts of drug resistant cases and PLHA(Patient Living With HIV AIDS) . Currently there are about 1200 CBNAAT and 200 TruNat laboratories in the country, at the district and in some cases at a sub-district level.

Culture and Drug Susceptibility Testing Labs

Advanced tests such as the Line Probe Assay, Liquid and Solid Culture, and Drug Susceptibility Testing are available at C&DST(Culture and Drug Sensitivity Testing) Labs are located at a few select places in the state, often within the IRL; these provide additional drug resistance/ susceptibility testing services for a number of Anti-TB drugs.

Treatment Services

Standardized treatment regimen composed of multiple anti-Tuberculosis drugs are provided through the program. Typically, drug regimen consist of an intensive phase of about two to six months and a longer continuation phase of four to one and half years.

Based on the nature of anti-microbial resistance to the disease different treatment regimen are offered through the program. New Cases and those which exhibit no resistance are offered a six-month, short course of the four first line drugs; Isoniazid-H: Rifampicin-R, Pyrazinamide-Z, and Ethambutol-E. The drugs are administered through daily weight band based doses of Fixed Dose Combinations, consisting of HRZE for the intensive phase of two months and HRE for the continuation phase of four months.[5] For drug resistant cases, depending upon the pattern of drug resistance a number of regimen are available composed of a combination of 13 drugs.

Public private partnership under RNTCP

In India a sizable proportion of the people with symptoms suggestive of pulmonary tuberculosis approach the private sector for their immediate health care needs. However, the private sector is overburdened, and lacks the capacity to treat such high volumes of patients. RNTCP-recommended Private-Provider Interface Agencies (PPIAs) help treat and track high volumes of patients through offering treatment vouchers, electronic case notification, and information systems for patient tracking.[6]

Due to lacking training and coordination amongst private providers, adherence to the RNTCP protocol is quite variable amongst private providers,[7] and less than 1% of private providers comply with all RNTCP recommendations.[8] There is need for regularizing the varied anti-tubercular treatment regimens used by general practitioners and other private sector players. The treatment carried out by the private practitioners vary from that of the RNTCP treatment. Once treatment is started in the usual way for the private sector, it is difficult for the patient to change to the RNTCP panel. Studies have shown that faulty anti-TB prescriptions in the private sector in India ranges from 50% to 100% and this is a matter of concern for the healthcare services in TB currently being provided by the largely unregulated private sector in India.

History

India has had a TB Control Program since 1962.[9] Since then it has re-organized itself two times; first into the Revised National Tuberculosis Control Program (RNTCP) in 1997 and then into the National Tuberculosis Elimination program in 2020.

National TB Program- NTP (1962-1997)

TB control efforts got organized with the National TB program (NTP) primarily focusing on BCG vaccinations as a preventive measure.

At that time, the Indian government lacked the financial backing to meet its public health goals. Therefore, external sources of funding and administration, often from the WHO and UN, became common in the realm of public health.[10] In 1992, the WHO and Swedish International Development Agency evaluated the NTCP, finding that it lacked funding, information on health outcomes, consistency across management and treatment regimens, and efficient diagnostic techniques.[8]

Revised National TB Control Program- RNTCP (1997-2020)

In order to overcome the deficiencies of the NTP, the Government decided to give a new thrust to TB control activities by revitalising the NTP, with assistance from international agencies, in 1993. Given TB's high curability rate 6–12 months after diagnosis, moving toward a clinical and treatment-based strategy was a sensible progression from the NTP.[11] The Revised National TB Control Programme (RNTCP) thus formulated, adopted the internationally recommended Directly Observed Treatment Short-course (DOTS) strategy, as the most systematic and cost-effective approach to revitalise the TB control programme in India. DOTS was adopted as a strategy for provision of treatment to increase the treatment completion rates. Political and administrative commitment were some of its core strategies, to ensure the provision of organized and comprehensive TB control services was obtained. Adoption of smear microscopy for reliable and early diagnosis was introduced in a decentralized manner in the general health services. Supply of drugs was also strengthened to provide assured supply of drugs to meet the requirements of the system.[12] The RNTCP was built on the infrastructure and systems built through the NTP. Major additions to the RNTCP, over and above the structures established under the NTP, was the establishment of a sub-district supervisory unit, known as a TB Unit, with dedicated RNTCP supervisors posted, and decentralization of both diagnostic and treatment services, with treatment given under the support of DOT (directly observed treatment) providers.

Large-scale implementation of the RNTCP began in late 1998.[13] Expansion of the programme was undertaken in a phased manner with rigid appraisals of the districts prior to starting service delivery. In the first phase of RNTCP (1998–2005), the programme's focus was on ensuring expansion of quality DOTS services to the entire country. The initial 5-year project plan was to implement the RNTCP in 102 districts of the country and strengthen another 203 Short Course Chemotherapy (SCC) districts for introduction of the revised strategy at a later stage. The Government of India took up the massive challenge of nationwide expansion of the RNTCP and covering the whole country under RNTCP by the year 2005, and to reach the global targets for TB control on case detection and treatment success. The structural arrangements for funds transfer and to account for the resources deployed were developed and thus the formation of the State and District TB Control Societies was under- taken. The systems were further strengthened and the programme was scaled up for national coverage in 2005. India achieved country wide coverage under RNTCP in March 2006.

This was followed up with RNTCP Phase II, developed based on the lessons learnt from the implementation of the programme over the previous 12-year period, from 2006 onwards. During this period the programme aimed to widen services both in terms of activities and access, and to sustain the achievements. The second phase aimed to maintain at least a 70% case detection rate of new smear positive cases as well as maintain a cure rate of at least 85%, in order to achieve the TB-related targets set by the Millennium Development Goals for 2015.[14] The design of the RNTCP II remained almost the same as that of RNTCP I but additional requirements of quality assured diagnosis and treatment were built in through schemes to increase the participation of private sector providers and also inclusion of DOTS+ for MDR TB and XDR TB. Systematic research and evidence building to inform the programme for better design was also included as an important component. The Advocacy, Communication and Social Mobilization were also addressed in the design. The challenges imposed by the structures under NRHM were also taken into account.

NIKSHAY, the web based reporting for TB programme has been another notable achievement initiated in 2012 and has enabled capture and transfer of individual patient data from the remotest health institutions of the country.

National TB Elimination Program- NTEP (2020-till date)

Consolidating a series of rapid and progressive advancements in RNTCP from 2016 onward, and with Government of India's commitment to achieve the END TB targets 5 years earlier, RNTCP was renamed as the National TB Elimination Program. The change came into effect from 1 January 2020.[15] This decision was declared by Special Secretary, Sanjeeva Kumar, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, in a letter to all the State Chief Secretaries.[16]

See also

References

- ↑ National Strategic Plan for Tuberculosis Control, 2017-2025. Central TB Division, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. June 2020.

- ↑ India TB Report 2019. New Delhi: Central TB Division, MoHFW. 2019. pp. 3–6.

- ↑ "WHO Supra-National Laboratory Network". Archived from the original on 30 October 2015.

- ↑ Technical and Operational Guidelines for TB Control in India 2016. New Delhi: Central TB Division, MoHFW. 2016. p. 10.

- ↑ "TOG-Chapter 4-Treatment of TB Part 1 :: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare". tbcindia.gov.in. Retrieved 21 June 2020.

- ↑ Wells, William A.; Uplekar, Mukund; Pai, Madhukar (2015). "Achieving Systemic and Scalable Private Sector Engagement in Tuberculosis Care and Prevention in Asia". PLOS Medicine. 12 (6): e1001842. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001842. PMC 4477873. PMID 26103555.

- ↑ Bronner Murrison, Liza; Ananthakrishnan, Ramya; Sukumar, Sumanya; Augustine, Sheela; Krishnan, Nalini; Pai, Madhukar; Dowdy, David W. (2016). "How do Urban Indian Private Practitioners Diagnose and Treat Tuberculosis? A Cross-Sectional Study in Chennai". PLOS ONE. 11 (2): e0149862. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1149862B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0149862. PMC 4762612. PMID 26901165.

- 1 2 Verma, R.; Khanna, P.; Mehta, B. (2013). "Revised national tuberculosis control program in India: The need to strengthen". International Journal of Preventive Medicine. 4 (1): 1–5. PMC 3570899. PMID 23413398.

- ↑ "Revised National Tuberculosis Control Programme | National Health Portal Of India". www.nhp.gov.in. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- ↑ Amrith, Sunil (2007). "Political Culture of Health in India: A Historical Perspective". Economic and Political Weekly. 42 (2): 114–121. JSTOR 4419132.

- ↑ Daftary, Amrita; Calzavara, Liviana; Padayatchi, Nesri (2015). "The contrasting cultures of HIV and tuberculosis care". AIDS. 29 (1): 1–4. doi:10.1097/QAD.0000000000000515. PMC 4770012. PMID 25387315.

- ↑ Sachdeva, K. S.; Kumar, A.; Dewan, P.; Kumar, A.; Satyanarayana, S. (2012). "New vision for Revised National Tuberculosis Control Programme (RNTCP): Universal access - "reaching the un-reached"". The Indian Journal of Medical Research. 135 (5): 690–694. PMC 3401704. PMID 22771603.

- ↑ "RNTCP | Government of India TB Treatment Education & Care". TB Facts.org. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- ↑ Mishra, Gyanshankar; Ghorpade, S. V.; Mulani, J. (2014). "XDR-TB: An outcome of programmatic management of TB in India". Indian Journal of Medical Ethics. 11 (1): 47–52. doi:10.20529/IJME.2014.013. PMID 24509111.

- ↑ Ravindranath, Prasad (17 January 2020). "India's TB control programme renamed to reflect its intent on ending TB". Science Chronicle. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- ↑ AuthorTelanganaToday. "TB eradication mission renamed". Telangana Today. Retrieved 2 January 2020.

External links

- Nikshay, A web based solution for monitoring of TB patients to monitor RNTCP

- Tuberculosis Control India's Homepage on RNTCP

- National Institute of Research in Tuberculosis, Chennai Tuberculosis Research Center, Chennai

- NTI Bangalore The National Tuberculosis Institute, Bangalore