The Revolt of Ghent was an uprising by the citizens of Ghent against the regime of the Holy Roman Emperor and Spanish king Charles V in 1539. The revolt was a reaction to high taxes, which the Flemish felt were used solely to fight wars abroad (in particular the Italian War of 1536–1538).[1] Charles marched his army into the city the following year and the rebels surrendered without a fight. Charles humiliated the rebels by parading their leaders in undershirts with hangman nooses around their necks. Since then Ghent citizens informally call themselves "noose bearers".[2]

Background

At this time, Ghent was subject to the rule of the Holy Roman Emperor and Spanish king Charles V, though it was his sister, Mary of Hungary, who actually governed the region as his regent. Ghent was in the Burgundian Circle of the Holy Roman Empire. Ghent and the Low Countries in general were an international center of trade and industry and therefore an important source of revenue. Ghent had lucrative commercial ties to France.[3] Ghent had a population of 40,000 to 50,000 people.[4]

In early 1515, Charles imposed upon Ghent the Calfvel[lower-alpha 1] edict, which, among other things, prevented the guilds from selecting their own deans.

In 1536, Charles went to war with the French king Francis I for control of northern Italy (the Italian War of 1536–38). Charles asked Mary to raise money and conscripts from the Dutch provinces. In late March 1537, Mary declared a levy of 1.2 million guilders and an army of 30,000 conscripts along with munitions and artillery. Flanders would have to pay a third of the money (400,000 guilders); Ghent was asked to contribute 56,000.[5] Ghent was already deep in debt due to fines imposed by its rulers in the previous century.[6]

Ghent refused to pay the taxes on the grounds that old pacts with previous rulers meant that no tax could be levied on Ghent without its consent, though they did offer to supply troops in lieu of money.[7] Mary tried haggling with Ghent's leaders, but Charles firmly insisted that Ghent pay its share without condition.[3]

Of the four Dutch provinces, Ghent was the only one to reject the new taxes.[8] When the other Dutch provinces refused to support Ghent, Ghent secretly offered its allegiance to the French king Francis I in exchange for protection from Charles. Francis rejected Ghent's petition, possibly because Charles had insinuated that he might give Francis control over Milan when he abdicated (this did not happen), and consequently Francis wanted to stay on good terms with Charles.[3]

In early 1539, Ghent threw a lavish rhetorician festival. The lavishness of the festival infuriated Charles' officials because Ghent claimed it couldn't afford to pay its taxes.[9]

In July 1539, rumors spread that certain aldermen had tampered with documents in the city's archives that legitimized Ghent's autonomy. In particular, the guilds were upset over the supposed theft of the Purchase of Flanders, a legendary document from a previous Flemish count which purportedly gave Ghent the right to reject all taxation. The guildsmen believed that their city's past and its rights had been altered and misrepresented.[10]

The revolt

On 17 August 1539 a number of guilds—which included the millers, the cordwainers, the old shoemakers, the smiths, and the shipmakers—demanded the right to choose their own deans and the arrest of the city's aldermen, who they believed had capitulated to Mary's demands against their wishes. Over the next few days, they armed themselves and took over the city, forcing the city's aldermen to flee or be imprisoned. On 21 August they formed a committee of nine men to administrate the city's affairs.[7] A 75-year-old retired alderman by the name of Lieven Pyn was executed on 28 August in part for supposedly tampering with documents that legitimized Ghent's autonomy.[7] Pyn was involved in tax negotiations back in 1537. He was tortured to death on the rack.[11] On 3 September the parchment upon which the Calfvel was written was ceremonially torn apart.

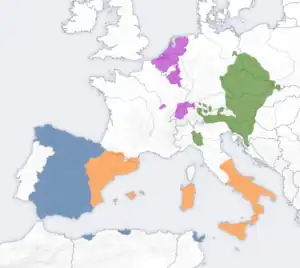

As a sign of his good intentions, Francis told Charles that Ghent had offered to defect to him. Seeing that the French king was cooperative, Charles decided it was time to suppress the revolt personally. He requested passage through French territory, which was granted. Charles did not want to sail to Flanders because he feared the English would try to capture him in the Channel. Charles set off from Spain with an entourage of about a hundred people.[3] Charles moved through France during the winter of 1539. On 12 December at Loches he met with Francis, who escorted him to Paris.[12] Moving on, Charles reached Valenciennes in January, where he met with his sister Mary as well as a delegation from Ghent. Charles warned them that he would make an example of Ghent.

Charles reached his Burgundian territories in late January. He met up with troops he had summoned from Germany, Spain, and the Netherlands.[3] Charles reached Ghent on 14 February[13] with an army of around 5,000 soldiers.[14] The city offered him no resistance as he entered.

Aftermath

The leaders of the revolt were arrested, of whom 25 were executed. The rest were humiliated: on May 3, they were marched through the streets from the town hall towards Charles' palace, the Prinsenhof. The procession consisted of all the city's sheriffs, clerks, officials, and 30 noblemen dressed in black robes and barefoot; 318 guild members and 50 weavers, they too dressed in black robes; and 50 day laborers dressed in white shirts with hangman's nooses around their necks.[15][16] The hangman's noose symbolized that they deserved the gallows. At the Prinsenhof, they were made to beg Charles and Mary for mercy.

A fine of 8,000 guilders was imposed on the city.[17] In late April, Charles decreed a new constitution, the Caroline Concession, that stripped Ghent of all its medieval legal and political freedoms, as well as all its weapons. The weavers and 53 other crafts guilds were merged into 21 corporations, and the privileges of all guilds save the shippers and butchers were stripped. The old abbey of Saint Bavo's and its church of the Holy Savior were demolished to make way for a new fortress, the Castle of the Spaniards (Spanjaardenkasteel), which housed a permanent garrison. Eight of the city's gates and parts of its walls were demolished. The city's aldermen would henceforth be selected by magistrates appointed by Charles' representatives.[18] Charles ordered the scaling back of festivals that fostered the city's civic pride.[19] The work clock in the belfry was taken down, because it was a symbol of political defiance as it had been used to summon assemblies of workers to the city's main square (the Vrijdagmarkt).[20]

Legacy

Since this incident the people of Ghent have taken on the sobriquet "noose bearers" (stroppendragers in Dutch). Every summer during the Ghent Festivities, the Guild of Noose Bearers commemorates the revolt by parading through the streets dressed in white shirts with nooses around their neck. The noose has also become an informal symbol of Ghent itself.

Re-enactors marching during the annual Ghent Festival. |  Statue of a noose bearer outside Charles' palace. |

Notes

References

- ↑ Kamen (2005)

- ↑ "History".

- 1 2 3 4 5 Robertson (1769)

- ↑ OPSTAND IN OUDENAARDE IN 1539-1540 pg 28

- ↑ Steyaert (1848)

- ↑ OPSTAND IN OUDENAARDE IN 1539-1540 pg 48

- 1 2 3 Arnade (1996), p. 201

- ↑ Bercé (1987), p. 43

- ↑ Arnade (1996), p. 200

- ↑ Arnade (1996), p. 202

- ↑ Crane 2014, p. .

- ↑ Ward (1929), p. 74

- ↑ Sources disagree on the exact day Charles entered Ghent. Bercé and Robertson say it was on the 24th. Arnade (1996) says it was on the 4th, but in his 2008 book he says it was on the 14th. Koenigsberger and Web sources say it was on the 14th.

- ↑ Tilly (1996), p. 58

- ↑ "Historiek | gildevandestroppendragers.be". Archived from the original on 17 August 2011. Retrieved 14 December 2014.

- ↑ "De Gilde van de Stroppendragers". gentschefieste.be. Retrieved 14 December 2014.

- ↑ OPSTAND IN OUDENAARDE IN 1539-1540 pg 81

- ↑ Arnade (1996), p. 263

- ↑ Arnade (2008), p. 150

- ↑ Arnade (1996), p. 206

Bibliography

- Arnade, Peter J. (1996). Realms of Ritual: Burgundian Ceremony and Civic Life in Late Medieval Ghent. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-3098-5.

- Arnade, Peter J. (2008). Beggars, Iconoclasts, and Civic Patriots: The Political Culture of the Dutch Revolt. Cornell University Press. ISBN 9780801474965.

- Bercé, Y.M (1987). Revolt and Revolution in Early Modern Europe: An Essay on the History of Political Violence. Manchester University Press. p. 43. ISBN 9780719019678. Retrieved 14 December 2014.

- Crane, Nicholas (2014). Mercator: The Man Who Mapped the Planet. Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 9781466880139.

- Kamen, Henry (2005). Spain, 1469–1714: A Society of Conflict (3rd ed.). Harlow, United Kingdom: Pearson Education. ISBN 0-582-78464-6.

- Koenigsberger, Helmut Georg (2001). Monarchies, States Generals and Parliaments: The Netherlands in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-80330-6.

- Robertson, William (1769). The History of the Reign of the Emperor Charles V.

- Steyaert, Judocus Johannes (1848). Ongeval van Lieven Pien (in Dutch).

- Tilly, C. (1996). European Revolutions: 1492-1992. Wiley. ISBN 9780631199038.

- Ward, Adolphus William, ed. (1929). The Cambridge Modern History. Vol. 12.

- "Gilde van de Stroppendragers". gildevandestroppendragers.be. Retrieved 25 August 2023.

- "De Gilde van de Stroppendragers". gentschefieste.be. Retrieved 14 December 2014.

- Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge (Great Britain) (1836). Penny Cyclopaedia of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. C. Knight. p. 500. Retrieved 14 December 2014.