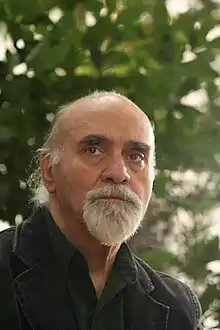

Reza Baraheni | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 13 December 1935 |

| Died | 25 March 2022 (aged 86) Toronto, Canada |

| Nationality | Iranian |

| Occupation(s) | Novelist, poet and critic |

Reza Baraheni (Persian: رضا براهنی; 13 December 1935 – 25 March 2022[1]) was an Iranian[2] novelist, poet, critic, and political activist.

Baraheni was born in Tabriz, Iran, in 1935. [3] After studying there and in Turkey, he obtained a Ph.D. in English literature from the University of Istanbul, and in 1963 was appointed Professor of English at Teheran University.[4]

Baraheni lived in Toronto, Canada, where he used to teach at the Centre for Comparative Literature at the University of Toronto.

He was the author of more than fifty books of poetry, fiction, literary theory, and criticism, written in Persian and English.

His works have been translated into a dozen of languages. His book, Crowned Cannibals, is accused by a few of containing some fabrications.[5] Moreover, he translated into Persian works by Shakespeare, Kundera, Mandelstam, Andrić, and Fanon.

Winner of the Scholars-at-Risk-Program Award of the University of Toronto and Massey College, Baraheni taught at the University of Tehran, Iran, the University of Texas at Austin, Indiana University in Bloomington, Indiana, the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, and York University. He was also a Fellow of St. Antony's College, Oxford University, Britain, Fellow of the University of Iowa, Iowa City, and Fellow of Winters College, York University. He was president of PEN Canada.

He died on 24 March 2022 in Toronto, Canada, and was buried on 9 April 2022 at Elgin Mills Cemetery, Canada.

Political life

Baraheni, along with his friends and fellow writers, Jalal Al-Ahmad and Gholamhossein Saedi, initiated the first steps in 1966, leading to the founding of the Writers Association of Iran in the following year. Their meeting with the Shah's Prime Minister Amir-Abbas Hoveida in that year led to an open confrontation with Shah's regime, placing the struggle for unhampered transmission of thought as a preliminary step towards genuine democracy on the agenda of Iran's contemporary history. Despite the struggle of some of the most famous writers of the country to turn the Writers Association of Iran[6] into an officially recognized human rights organization, Shah’s government suppressed the association, intimidated many of its members, arresting and torturing some of its members, among them Baraheni, who had returned from the United States after the completion of a year-long teaching position in Texas and Utah. In 1973, he was arrested and imprisoned in Tehran. Baraheni claimed he was tortured and imprisoned for 104 days (See God’s Shadow, Prison Poems, 1976; The Crowned Cannibals, 1977, Introduction by E.L. Doctorow).

Back in the United States a year later, Baraheni joined the American branch of the International PEN, working very closely with Edward Albee, Allen Ginsberg, Richard Howard, and others at PEN’s Freedom to Write Committee, sharing at the same time, with Kay Boyle, the Honorary Chair of the Committee for Artistic and Intellectual Freedom (CAIFI) to release Iranian writers and artists from prison. He published his prose and poetry in the Time Magazine, the New York Times, the New York Review of Books, and the American Poetry Review.

In 1976, during his exile in the U.S., human rights organizations were led to believe that the Shah’s SAVAK agents had arrived in the U.S. to assassinate Iranian opposition leaders, among them Baraheni. With the help of the American PEN and the assistance of Ramsey Clark, Baraheni says he was able to expose Shah’s plot.

Baraheni wrote a four-page article in the February 1977 edition of the erotic magazine, Penthouse, claiming how political prisoners in Iran under the Shah were tortured. He alleged how the political prisoners and their family members were raped systematically in Iran under the Shah. His claims, however, have been disputed by many other Iranians who say he either exaggerated or made them up to get his readers' attention in the West. He was influential in turning public opinion in the West against the Shah of Iran, and especially amongst the Democratic Party in the US. See Report by Robert C. de Camara on Shah's record.

Baraheni returned to Iran in the company of more than thirty other intellectuals in 1979, four days after the Shah fled the country. Baraheni tried very hard to win favors with Ayatollah Khomeini. On 30 January 1979, he wrote in the Etell'at newspaper, "Soon [after Khomeini's return] there will be a permanent and deep democracy in Iran, and we will enter an era where poverty, repression, bankruptcy, hopelessness, and capitalist greed will end, and Iran will be saved from economic chaos and bad governmental planning". However, Khomeini ignored Baraheni's flattery; instead, he joined his Leftist friends in the Writer's Association.

Baraheni’s concentration was on three major themes: 1)the unhampered transmission of thought, 2)equal rights for oppressed nationalities in Iran and; 3)equal rights for women with men. In the wave of the crackdown against the intellectuals, the liberals, and the left in Iran in 1981, Baraheni found himself once more in solitary confinement, this time under the new regime. Upon his release from prison in the winter of 1982 under international pressure, he was fired on the trumped up charge of cooperating with counter-revolutionary groups on the campus of the University of Tehran. He was not allowed to leave the country for many years.

With the death of Khomeini, senior members of the Writers Association of Iran, Baraheni among them, decided that they should revive the association. They formed the Consulting Assembly of the Writers Association of Iran, and wrote two texts of utmost importance. Baraheni was one of the three members of the Association who wrote the “Text of 134 Iranian Writers.” He was one of the “Group of Eight” who undertook the job of getting the signatures of other Iranian writers. He was also secretly assigned to send the text to his connections abroad. Baraheni translated the Text into English and sent it to the International PEN.

The second text was the re-writing of the charter of the Writers Association of Iran. Several times, Baraheni and two other senior members of the association were called by the Revolutionary Tribunal of the Islamic Republic of Iran, asking them to withdraw their signatures from the resolutions of the association. Baraheni was told that he was a persona non grata. He knew that he had to leave the country. Baraheni made arrangements with Swedish friends to flee Iran and travel to Sweden. With the help of Eugene Schoulgin, head of the International PEN’s “Writers in Prison Committee,” and Ron Graham, the President of PEN Canada in 1996, Baraheni sought asylum in Canada. He arrived in Canada in January 1997. He later became the President of PEN Canada (2000–2002). During his presidency, Baraheni recommended a change in the Charter of the International PEN to permit the inclusion of all kinds of literature in the charter.

He lived in Canada where he was a visiting professor at the University of Toronto’s Centre for Comparative Literature and past president of PEN Canada from June 2001-June 2003. He was also the featured poet in the Hart House Review's 2007 edition, which featured exiled writers and artists.

His most famous work is The Crowned Cannibals: Writings on Repression in Iran, which recounts his days in prison against the Shah of Iran. He also spoke against the discriminative treatment of his Azerbaijani background by the Iranian intelligentsia during Mohammed Reza Shah's rule.[lower-alpha 1][8]

Bibliography

English

- God's shadow : prison poems (Indiana University Press, Bloomington - 1976)

- The crowned cannibals: Writings on repression in Iran (Random House, Vintage, New York - 1977, introduction by E. L. Doctorow)

Anthologies

- Approaching Literature in the 21st Century - ed. Peter Schakel and Jack Ridl (Bedford/St. Martin’s, Boston - 2005)

- God’s Spies - ed. Alberto Manguel (Macfarlane, Walter & Ross, Toronto - 1999)

- The Prison where I Live, ed. Siobhan Dowd, Foreword by Joseph Brodsky (Cassell, London - 1996)

French

Novels

Written in Persian:

- Les saisons en enfer du jeune Ayyaz (Pauvert - Paris, 2000)

- Shéhérazade et son romancier (2ème éd.) (Fayard - Paris, 2002)

- Elias à New-York (Fayard - Paris, 2004)

- Les mystères de mon pays - vol. 1 (Fayard - Paris, 2009)

- Les mystères de mon pays - vol. 2 (Fayard - Paris, to be published 2012)

Short stories and other texts

Poems

- Aux papillons (excerpts) (Revue Diasporiques n°11 - Paris, 2010)

Notes

- ↑ Reza Baraheni, another native of Azerbaijan, is particularly scathing in describing how some of the Persian-speaking intelligentsia approached his Azeri heritage during Mohammed Reza Shah's rule:

I learned Persian at great cost to my identity as an Azerbaijani Turk, and only after I had mastered this language and was on the point of becoming thoroughly Persianized was I reminded of my roots by those who were directing polemics against me in the Persian press.

Whenever I wrote something good about an original Persian author, I was hailed as a man who had finally left behind his subhuman Turkish background and should be considered as great as the Persians. Whenever I said something derogatory about a writer's work, the response was that I was an Azerbaijani.. [and] whatever I had written could be of no significance at all… When I finally succeeded in establishing myself in their literary Who's Who in their own language and on their own terms, they came up with the sorry notion that there was not even a single drop of Azerbaijani blood in my veins— [7]

References

- ↑ "رضا براهنی، شاعر و نویسنده برجسته ایرانی، درگذشت". رادیو فردا. 25 March 2022.

- ↑ The Rising Tide of Cultural Pluralism: The Nation-State at Bay? by Crawford Young, 1993, p. 126.

- ↑ https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1080/03064227608532493

- ↑ https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1080/03064227608532493

- ↑ Rewriting the Iranian Revolution: https://newrepublic.com/article/143713/rewriting-iranian-revolution

- ↑ Writers Association of Iran: http://www.iisg.nl/archives/en/files/i/10886062.php

- ↑ Yekta Steininger, Maryam Y. (2010). The United States and Iran: different values and attitudes toward nature. University Press of America. ISBN 9780761846154.

- ↑ Baraheni, Reza (2005). "The Midwife of My Land" (PDF). Idea&s Magazine. Faculty of Arts & Science, University of Toronto. 2 (1): 73. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 April 2012.

External links

- Open Library

- '"Anthology of poems in Persian"'

- "Addressing Butterflies : a Poetry Collection in Persian; 2/9"

- "Addressing Butterflies : a Poetry Collection in Persian; 3/9"

- "Addressing Butterflies : a Poetry Collection in Persian; 4/9"

- "Addressing Butterflies : a Poetry Collection in Persian; 5/9"

- "Addressing Butterflies : a Poetry Collection in Persian; 6/9"

- "Addressing Butterflies : a Poetry Collection in Persian; 7/9"

- "Addressing Butterflies : a Poetry Collection in Persian; 8/9"

- "Addressing Butterflies : a Poetry Collection in Persian; 9/9"

- http://www.iisg.nl/archives/en/files/i/10886062.php

- https://web.archive.org/web/20080921230538/http://www.radiozamaneh.org/literature/2006/12/post_93.html