| Battle of Rhode Island | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Revolutionary War | |||||||

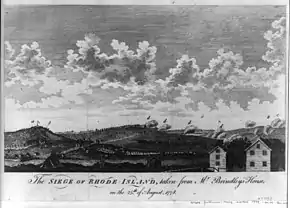

A 1779 print depicting the battle | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

John Sullivan Nathanael Greene Christopher Greene Comte d'Estaing |

Sir Robert Pigot Francis Smith Richard Prescott Friedrich Wilhelm von Lossberg | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 10,100? | 6,700[1] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

30 killed 137 wounded 44 missing[2] |

38 killed 210 wounded 12 missing[2] | ||||||

The Battle of Rhode Island (also known as the Battle of Quaker Hill[3]) took place on August 29, 1778. Continental Army and Militia forces under the command of Major General John Sullivan had been besieging the British forces in Newport, Rhode Island, which is situated on Aquidneck Island, but they had finally abandoned their siege and were withdrawing to the northern part of the island. The British forces then sortied, supported by recently arrived Royal Navy ships, and they attacked the retreating Americans. The battle ended inconclusively, but the Continental forces withdrew to the mainland and left Aquidneck Island in British hands.

The battle was the first attempt at cooperation between French and American forces following France's entry into the war as an American ally. Operations against Newport were planned in conjunction with a French fleet and troops, but they were frustrated in part by difficult relations between the commanders, as well as by a storm that damaged both French and British fleets shortly before joint operations were to begin.

The battle was also notable for the participation of the 1st Rhode Island Regiment under the command of Colonel Christopher Greene, which consisted of blacks, American Indians, and White colonists.[4]

Background

On December 8, 1776, Britain's Lieutenant General Henry Clinton led an expedition from New York City to take control of Rhode Island. The British expeditionary forces under Brigadier General Richard Prescott, with several Hessian regiments of foot, landed and seized control of Newport, Rhode Island.[5] France formally recognized the United States of America in February 1778 following the surrender of the British Army after the Battles of Saratoga in October 1777. War was declared between France and Great Britain in March 1778.[6]

French movements

France sent Admiral Comte d'Estaing with a fleet of 12 ships of the line and 4,000 French Army troops[7] to America in April in its first major attempt at cooperation with the Americans, with orders to blockade the British fleet in the Delaware River.[8] British leaders had early intelligence that d'Estaing was headed for America, but political and military differences within the government and navy delayed the British response, and he sailed unopposed through the Straits of Gibraltar. It was not until early June that a fleet of 13 ships of the line left European waters in pursuit, under the command of Vice-Admiral John Byron.[9][10] D'Estaing's crossing of the Atlantic took three months, but Byron was also delayed due to bad weather and did not reach New York until mid-August.[8][11]

The British evacuated from Philadelphia to New York City before d'Estaing's arrival. Their fleet was no longer on the river when the French fleet arrived at Delaware Bay in early July.[8] D'Estaing decided to sail for New York, but its well-defended harbor presented a daunting challenge.[12] The French and their American pilots believed that d'Estaing's largest ships would be unable to cross the bar into New York harbor, so French and American leaders decided to deploy their forces against British-occupied Newport, Rhode Island.[13] While d'Estaing was outside the harbor, British General Henry Clinton and Vice-Admiral Richard Howe dispatched a fleet of transports carrying 2,000 troops to reinforce Newport via Long Island Sound. The troops reached their destination on July 15, raising the size of Major General Robert Pigot's garrison to more than 6,700 men.[14]

American forces

American and British forces had been in a standoff on Rhode Island since the British occupation began in late 1776. Major General Joseph Spencer of the Rhode Island defenses had been ordered by Major General George Washington to launch an assault on Newport in 1777, but he had not done so and was removed from command. In March 1778, Congress approved the appointment of Major General John Sullivan to Rhode Island. By early May, Sullivan had arrived in the state and produced a detailed report on the situation.[15] He began logistical preparations for an attack on Newport, caching equipment and supplies on the eastern shore of Narragansett Bay and the Taunton River. British General Pigot was aware of Sullivan's preparations and launched an expedition on May 25 that raided Bristol and Warren. This destroyed military supplies and plundered the towns.[16][17] Sullivan's response was to make renewed appeals for assistance, which were reinforced by a Congressional declaration after a second raid on Freetown on May 31.[18]

General Washington wrote to Sullivan on July 17 ordering him to raise 5,000 troops for possible operations against Newport. Sullivan did not receive this letter until July 23, and it was followed the next day by the arrival of Colonel John Laurens with word that Newport had been chosen as the allied target on the 22nd Regiment, and that he should raise as large a force as possible.[19] Sullivan's force at that time amounted to 1,600 troops.[19] Laurens had left Washington's camp on the 22nd, riding ahead of a column of Continental troops (the brigades of John Glover and James Mitchell Varnum) led by the Marquis de Lafayette.[20]

News of the French involvement rallied support for the cause, and militia began streaming to Rhode Island from neighboring states. Half the Rhode Island militia was called up and led by William West, and large numbers of militia from Massachusetts and New Hampshire along with the Continental Artillery came to Rhode Island to join the effort. However, these forces took some time to muster, and the majority of them did not arrive until the first week of August.[21] Washington sent Major General Nathanael Greene, a Rhode Island native and reliable officer, to further bolster Sullivan's leadership corps on July 27. Sullivan had been regularly criticized in Congress for his performance in earlier battles, and Washington urged him to take counsel from Greene and Lafayette. Greene wrote to Sullivan on the matter and reinforced the need for a successful operation.[22]

Prelude

French arrival at Newport

D'Estaing sailed from his position outside the New York harbor on July 22, when the British judged the tide high enough for the French ships to cross the bar.[13] He initially sailed south before turning northeast toward Newport.[23] The British fleet in New York consisted of eight ships of the line under the command of Admiral Howe, and they sailed out after him once they discovered that his destination was Newport.[24] D'Estaing arrived off Point Judith on July 29 and immediately met with Generals Greene and Lafayette to develop their plan of attack.[25] Sullivan's proposal was that the Americans would cross over to Aquidneck Island's eastern shore from Tiverton, while French troops would use Conanicut Island as a staging ground and cross from the west, cutting off a detachment of British soldiers at Butts Hill on the northern part of the island.[26] The next day, d'Estaing sent frigates into the Sakonnet River (the channel to the east of Aquidneck) and into the main channel leading to Newport.[25]

As allied intentions became clear, General Pigot decided to deploy his forces in a defensive posture, withdrawing troops from Conanicut Island and from Butts Hill. He also decided to move nearly all livestock into the city, ordered the leveling of orchards to provide a clear line of fire, and destroyed carriages and wagons.[27] The arriving French ships drove several of his supporting ships aground, which were burned to prevent their capture. As the French worked their way up the channel toward Newport, Pigot ordered the remaining ships to be scuttled to hamper French access to Newport's harbor. On August 8, d'Estaing moved the bulk of his fleet into Newport Harbor.[24]

On August 9, d'Estaing began disembarking some of his 4,000 troops onto Conanicut Island. The same day, General Sullivan learned that Pigot had abandoned Butts Hill. Contrary to the agreement with d'Estaing, Sullivan crossed troops over to seize that high ground, concerned that the British might reoccupy it in strength. D'Estaing later approved of the action, but his initial reaction and that of some of his officers was disapproval. John Laurens wrote that the action "gave much umbrage to the French officers".[28]

Storm damage

Howe's fleet was delayed departing New York by contrary winds, and he arrived off Point Judith on August 9.[29] D'Estaing feared that Howe would be further reinforced and eventually gain a numerical advantage, so he boarded the French troops and sailed out to do battle with Howe on August 10.[24] The weather deteriorated into a major storm as the two fleets maneuvered for position and prepared to battle. The storm raged for two days and scattered both fleets, severely damaging the French flagship.[30] It also frustrated Sullivan's plans to attack Newport without French support on August 11.[31] Sullivan began siege operations while awaiting the return of the French fleet, moving closer to the British lines on August 15 and opening trenches to the northeast of the fortified British line north of Newport the next day.[32]

As the two fleets sought to regroup, individual ships encountered one another, and there were several minor naval skirmishes; two French ships were badly mauled in these encounters, including d'Estaing's flagship.[30] The French fleet regrouped off Delaware and returned to Newport on August 20, while the British fleet regrouped at New York.[33]

French retreat to Boston

Admiral d'Estaing was pressured by his captains to immediately sail for Boston to make repairs, but he instead sailed for Newport to inform the Americans that he would not be able to assist them. He informed Sullivan upon his arrival on August 20; Sullivan argued that the British could be compelled to surrender in just one or two days if the French remained to help, but d'Estaing refused. d'Estaing wrote that it was "difficult to persuade oneself that about six thousand men well entrenched and with a fort before which they had dug trenches could be taken either in twenty-four hours or in two days."[34] Any thought of the French fleet remaining at Newport was also opposed by d'Estaing's captains, with whom he had a difficult relationship due to his arrival in the navy at a high rank after service in the French army.[34] The fleet sailed for Boston on August 22.[35]

The French decision brought on a wave of anger in the American rank and file, as well as among its commanders. General Greene wrote a complaint which John Laurens termed "sensible and spirited", but General Sullivan was less diplomatic.[35] He wrote a missive containing much inflammatory language, in which he called d'Estaing's decision "derogatory to the honor of France", and he included further complaints in orders of the day that were later suppressed when tempers had cooled.[36] American soldiers called the French decision a "desertion" and noted that the French forces "left us in a most Rascally manner".[37]

The French departure prompted a mass exodus of the American militia, significantly shrinking the American force,[38] many of whom had only enlisted for a 20-day stint.[39] On August 24, Sullivan was alerted by General Washington that Clinton in New York was assembling a relief force. That evening, his council made the decision to withdraw to positions on the northern part of the island.[40] Sullivan continued to seek French assistance, dispatching Lafayette to Boston to negotiate further with d'Estaing,[41] but this proved fruitless in the end. D'Estaing and Lafayette met fierce criticism in Boston, Lafayette remarking that "I am more upon a warlike footing in the American lines than when I came near the British lines at Newport."[42]

In the meantime, the British in New York had not been idle. Howe was reinforced by the arrival of ships from Byron's storm-tossed squadron, and he sailed out to catch d'Estaing before he reached Boston. General Clinton organized a force of 4,000 men under Major General Charles Grey and sailed with it on August 26, destined for Newport.[43]

Battle

On the morning of August 28, the American war council decided to withdraw the last troops from their siege camps. They had engaged the British with occasional rounds of cannon fire for a few days, as some of their equipment was being withdrawn. Deserters had made General Pigot aware of the American plans to withdraw on August 26, so he was prepared to respond when they withdrew that night.[44]

The American generals established a defensive line across the entire island just south of a valley that cut across the island, hoping to deny the British the high ground in the north. They organized their forces in two sections:

- On the west, General Greene concentrated his forces in front of Turkey Hill but sent the 1st Rhode Island to establish advanced positions a half mile (1 km) south under the command of Brigadier General James Varnum.

- On the east, Brigadier General John Glover concentrated his forces behind a stone wall overlooking Quaker Hill.

The British organized their attack in a corresponding way, sending Hessian General Friedrich Wilhelm von Lossberg up the west road and Major General Francis Smith up the east road with two regiments each, under orders not to make a general attack. As it turned out, this advance led to the main battle.

Smith's assault on the American left

Smith's advance stalled when it came under fire from troops commanded by Lt. Col. Henry Brockholst Livingston, who was stationed at a windmill near Quaker Hill. Pigot sent word to Major General Richard Prescott to dispatch the 54th Regiment and Montfort Browne's Prince of Wales' American Regiment to reinforce Smith.[45] Thus reinforced, Smith returned to the attack, sending the 22nd and 43rd Regiments and the flank companies of the 38th Regiment and 54th Regiments against Livingston's left flank. Livingston had also been reinforced with Col. Edward Wigglesworth's 13th Massachusetts Regiment, sent by Sullivan, but he was nevertheless driven back to Quaker Hill. Then, with a German regiment threatening to outflank Quaker Hill itself, Livingston and Wigglesworth abandoned the hill and retreated all the way to Glover's lines. Smith made a probing attack but was repulsed by Glover's troops. "Seeing the strength of the American position, Smith decided against launching a major assault".[46] This ended the fighting on the American left.

Lossberg's assault on the American right

By 7:30 a.m., Lossberg had advanced against the American Light Corps under Col. John Laurens, who were positioned behind some stone walls south of the Redwood House. Lossberg pushed Laurens' men back onto Turkey Hill with the Hessian chasseurs, Huyne's Hessian regiment, and Edmund Fanning's King's American Regiment. Laurens had been reinforced by a regiment sent by Sullivan, but Lossberg stormed Turkey Hill and drove the defenders back on Nathanael Greene's wing of the army before starting a cannonade of Greene's lines.[47]

By 10 a.m., the sixth-rate HMS Sphynx, the converted merchantman HMS Vigilant, and the row galley HMS Spitfire Galley had negotiated the passage between Rhode Island (Aquidneck) and Prudence Island and commenced a bombardment of Greene's troops on the American right flank.[48] Lossberg now attacked Greene. German troops assailed Major Ward's 1st Rhode Island Regiment three times during the battle and were repulsed each time. The Germans then bayoneted the American wounded as they fell back. Meanwhile, Greene's artillery and the American battery at Bristol Neck concentrated their fire on the three British ships and drove them off.

At 2 p.m., Lossberg once again attacked Greene's positions without success. Greene counterattacked with Col. Israel Angell's 2nd Rhode Island Regiment, Brigadier General Solomon Lovell's brigade of Massachusetts militia, and Henry Brockholst Livingston's troops. Failing in a frontal attack, Greene sent his 1,500 men forward to try to turn Lossberg's right flank. Heavily outnumbered, Lossberg withdrew to the summit of Turkey Hill. By 3 p.m., Greene's wing was holding a stone wall three hundred paces from the foot of Turkey Hill. Towards evening, Greene attempted to cut off the Hessians on Lossberg's left flank, but Huyne's Hessians and Fanning's Provincials drove them off.[49] This ended the battle, although some artillery fire went on through the night. The British suffered 260 casualties, of whom 128 were German.[50]

Aftermath

Continental forces withdrew to Bristol and Tiverton on the night of August 30, leaving Rhode Island (Aquidneck Island) under British control. However, their withdrawal was orderly and unhurried. According to an account in the New Hampshire Gazette, it was accomplished "in perfect order and safety, not leaving behind the smallest article of provision, camp equipage, or military stores."[51]

The inflammatory writings of General Sullivan reached Boston before the French fleet arrived, and Admiral d'Estaing's initial reaction was reported to be a dignified silence. Politicians worked to smooth over the incident under pressure from Washington and the Continental Congress, and d'Estaing was in good spirits when Lafayette arrived in Boston. He even offered to march troops overland to support the Americans: "I offered to become a colonel of infantry, under the command of one who three years ago was a lawyer, and who certainly must have been an uncomfortable man for his clients."[52]

The relief force of Clinton and Grey arrived at Newport on September 1.[43] Given that the threat was over, Clinton ordered Grey to raid several communities on the Massachusetts coast.[53] Admiral Howe was unsuccessful in his bid to catch up with d'Estaing, who held a strong position at the Nantasket Roads when Howe arrived there on August 30.[54] Byron succeeded Howe as head of the New York station in September, but he also was unsuccessful in blockading d'Estaing. His fleet was scattered by a storm when it arrived off Boston, after which d'Estaing slipped away, bound for the West Indies.[55][56]

General Pigot was harshly criticized by Clinton for failing to await the relief force, which might have entrapped the Americans on the island.[57] He left Newport for England not long after. The British abandoned Newport in October 1779, leaving behind an economy ruined by war.[58]

Legacy

The Battle of Rhode Island Site was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1974 and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. It partially preserves the ground on which the battle was fought.[59][60] The underwater site of HMS Cerberus and HMS Lark is also on the Register, two Royal Navy ships scuttled during the French fleet's advance on Newport. Also listed are Fort Barton, one of the American defenses in Tiverton, and the Conanicut Battery, an earthworks on Conanicut Island built in 1775 and expanded by the British during their occupation of Newport.[60][61] The site was abandoned by the British after the arrival of the French fleet. The Joseph Reynolds House in Bristol was used by General Lafayette as his headquarters during the campaign; it is a National Historic Landmark and one of the oldest buildings in Rhode Island.[60][62]

Order of battle

See also

- Prince Greene

- American Revolutionary War § Stalemate in the North. Places 'Battle of Rhode Island' in overall sequence and strategic context.

Footnotes

- ↑ Dearden, p. 49

- 1 2 Boatner, p. 793

- ↑ Heitman, p. 354

- ↑ "Pines Bridge Monument". Yorktownhistory.org. Retrieved 2016-07-24.

- ↑ Schroder, p. 62.

- ↑ Morrissey, pp. 26–27

- ↑ Schroder, p. 138

- 1 2 3 Morrissey, p. 77

- ↑ Schaeper, pp. 152–153

- ↑ Daughan, p. 172

- ↑ Douglas, W. A. B. (1979). "Byron, John". In Halpenny, Francess G (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. IV (1771–1800) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press. Retrieved 2011-11-10.

- ↑ Daughan, pp. 174–175

- 1 2 Morrissey, p. 78

- ↑ Dearden, pp, 36, 49

- ↑ Murray, p. 6

- ↑ Murray, p. 8

- ↑ Dearden, pp. 25–27

- ↑ Dearden, p. 28

- 1 2 Dearden, p. 38

- ↑ Dearden, p. 37

- ↑ Dearden, pp. 51, 93

- ↑ Dearden, p. 45

- ↑ Mahan, p. 361

- 1 2 3 Daughan, p. 177

- 1 2 Daughan, p. 176

- ↑ Dearden, pp. 68–71

- ↑ Dearden, p. 61

- ↑ Dearden, pp. 74–75

- ↑ Dearden, p. 76

- 1 2 Mahan, p. 362

- ↑ Daughan, p. 179

- ↑ Dearden, pp. 95–98

- ↑ Mahan, p. 363

- 1 2 Dearden, p. 101

- 1 2 Dearden, p. 102

- ↑ Dearden, pp. 102, 135

- ↑ Dearden, p. 106

- ↑ Daughan, pp. 179–180

- ↑ Schroder, pp. 141–142

- ↑ Dearden, pp. 114–116

- ↑ Dearden, p. 118

- ↑ Patterson, Benton Rain (2004). Washington and Cornwallis: The Battle for America, 1775–1783. Taylor Trade Publishing. p. 185. ISBN 978-1-4617-3470-3.

- 1 2 Nelson, p. 63

- ↑ Dearden, pp. 118–120

- ↑ Dearden, p. 121

- ↑ Dearden, pp. 122–123

- ↑ Dearden, pp. 120–122

- ↑ Abbass, D. K. (2009). "The Forgotten Ships of the Battle of Rhode Island" (PDF). The Rhode Island Historical Society. Retrieved 25 April 2015.

- ↑ Dearden, pp. 124–126

- ↑ Dearden, p. 126

- ↑ "Americans Evacuate Rhode Islande". New Hampshire Gazette. 15 September 1778. Retrieved 2013-01-18.

- ↑ Dearden, p. 134

- ↑ Nelson, pp. 64–66

- ↑ Gruber, p. 319

- ↑ Colomb, p. 384

- ↑ Gruber, pp. 323–324

- ↑ Dearden, p. 128

- ↑ Dearden, pp. 142–143

- ↑ "Site of Battle of Rhode Island". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Archived from the original on 2011-06-06. Retrieved 2008-02-21.

- 1 2 3 "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. January 23, 2007.

- ↑ "Jamestown Historical Society: Battery". Archived from the original on 2012-03-31. Retrieved 2011-11-11.

- ↑ "Joseph Reynolds House". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Archived from the original on 2011-06-06. Retrieved 2008-06-29.

References

- Boatner, Mark Mayo (1966). Cassell's Biographical Dictionary of the American War of Independence, 1763–1783. London: Cassell & Company Ltd. ISBN 0-304-29296-6.

- Butler, Gerald W; Shaner, Richard (2001). The Guns of Boston Harbor: From the Bay Colony Through the Present. AuthorHouse. ISBN 978-0759647305.

- Colomb, Philip (1895). Naval Warfare, its Ruling Principles and Practice Historically Treated. London: W. H. Allen. p. 384. OCLC 2863262.

- Daughan, George (2011) [2008]. If By Sea: The Forging of the American Navy – from the Revolution to the War of 1812. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-02514-5. OCLC 701015376.

- Dearden, Paul F (1980). The Rhode Island Campaign of 1778. Providence, RI: Rhode Island Bicentennial Federation. ISBN 978-0-917012-17-4. OCLC 60041024.

- Gruber, Ira (1972). The Howe Brothers and the American Revolution. New York: Atheneum Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-1229-7. OCLC 1464455.

- Hattendorf, John B. (2018). Mary Gould Almy's Journal during the Siege of Newport, Rhode Island, 29 July to 24 August 1778. A Facsimile, Transcribed, Annotated, and Edited by John B. Hattendorf. Rhode Island: Rhode Island Sons of the Revolution. ISBN 978-1-54394-901-8.

- Heitman, Francis B. (1965) [1903]. Historical Register and Dictionary of the United States Army, from its Organization, September 29, 1789, to March 2, 1903. Volume 2. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

- Jaques, Tony (2006). Dictionary of Battles and Sieges: A Guide to 8500 Battles from Antiquity Through the Twenty-first Century. Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0313335365.

- Lippitt, Charles Warren (1915). The Battle of Rhode Island. Newport, RI: Mercury Publishing. OCLC 9887723.

- Mahan, Alfred T (1890). The Influence of Sea Power Upon History, 1660–1783. Boston: Little, Brown. p. 360. OCLC 746949269.

- McBurney, Christian M. (2011). The Rhode Island Campaign: The First French and American Operation in the Revolutionary War. Yardley, PA: Westholme. ISBN 978-1-59416-134-6.

- Morrissey, Brendan (2004). Monmouth Courthouse 1778: The Last Great Battle in the North. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84176-772-7. OCLC 56351768.

- Murray, Thomas Hamilton (1902). Gen. John Sullivan and the Battle of Rhode Island: a Sketch of the Former and a Description of the Latter. Providence, RI: The American-Irish Historical Society. p. 5. OCLC 2853550.

- Nelson, Paul (1996). Sir Charles Grey, First Earl Grey: Royal Soldier, Family Patriarch. Madison, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-0-8386-3673-2. OCLC 33820307.

- Schaeper, Thomas (2011). Edward Bancroft: Scientist, Author, Spy. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-11842-1. OCLC 178289618.

- Schroder, Walter (2009). The Hessian Occupation of Newport and Rhode Island 1776–1779. Westminster, MD: Heritage Books. ISBN 978-0-7884-4074-8. OCLC 497813357.

External links

- Battle of Rhode Island Map from the Rhode Island State Archives