| Richard J. Daley Center | |

|---|---|

Richard J. Daley Center in 2006 | |

| Record height | |

| Tallest in Chicago from 1965 to 1969[I] | |

| Preceded by | Chicago Board of Trade Building |

| Surpassed by | John Hancock Center |

| General information | |

| Architectural style | International Style |

| Location | Chicago, Illinois, United States |

| Address | 55 West Randolph Street |

| Coordinates | 41°53′02″N 87°37′49″W / 41.88393°N 87.63020°W |

| Construction started | 1963 |

| Completed | 1965 |

| Height | |

| Architectural | 648 ft (198 m) |

| Roof | 648 ft (198 m) |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 32 |

| Floor area | 136,102 m²[1] |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Jacques Brownson C.F. Murphy Associates Skidmore Owings & Merrill Loebl, Schlossman, Bennett & Dart |

| Main contractor | American Bridge Company, Gust K. Newberg Construction Co.[2] |

| Website | |

| thedaleycenter | |

| References | |

| [3][2] | |

The Richard J. Daley Center, also known by its open courtyard Daley Plaza and named after longtime mayor Richard J. Daley, is the premier civic center of the City of Chicago in Illinois. The Center's modernist skyscraper primarily houses offices and courtrooms for the Cook County Circuit Courts, Cook County States Attorney and additional office space for the City and the County. It is adjacent to the City Hall-County Building. The open granite-paved plaza used for gatherings, protests, and events is also the site of the Chicago Picasso, a gift to the city from the artist.

Situated on Randolph Street and Washington Street between Dearborn Street and Clark Street, the Richard J. Daley Center, with its "majestic" interior spaces, is considered a significant example of modernist Chicago architecture.[4] The main building was designed in the International Style of the Second Chicago School by Jacques Brownson of the firm C. F. Murphy Associates as supervising architects, with Skidmore, Owings & Merrill and Loebl, Schlossman, Bennett & Dart as associated architects,[5] and was completed in 1965.[3] At the time it was the tallest building in Chicago, but only held this title for four years until the John Hancock Center was completed. Originally known as the Chicago Civic Center, the building was renamed for Mayor Daley on December 27, 1976, seven days after his death in office.[6] The 648-foot (198 m), thirty-one story building features Cor-Ten, a self-weathering steel. Cor-Ten was designed to rust, actually strengthening the structure and giving the building its distinctive red and brown color. The Daley Center has 30 floors above its double height lobby, and is the tallest flat-roofed building in the world with fewer than 40 stories (a typical 648-foot (198 m) building would have 50-60 stories).

Building features

The Richard J. Daley Center houses more than 120 court and hearing rooms as well as the Cook County Law Library, offices of the Clerk of the Circuit Court, and certain court-related divisions of the Sheriff's Department. The building also houses office space for both the city and Cook County, of which the City of Chicago is its seat of government. The windows are cor-ten steel and bronze/white tinted.

Daley Plaza

Daley Plaza is the courtyard adjacent to the building, occupying the southern half of the block occupied by the building.

The plaza is dominated by an untitled Cor-ten steel 50-foot (15 m) sculpture by Pablo Picasso (usually called "The Picasso"). Completed in 1967, it was a gift to the City of Chicago from the artist. Though controversial for its abstract form, it quickly became a Chicago landmark. The plaza also features an in-ground fountain and an eternal flame memorial to the dead from World War I, World War II, the Korean War and the Vietnam War.

The plaza serves as a location for many civic functions including weekly farmers' markets in the summer, regular ethnic festivals, and the meeting place for Chicago's Critical Mass ride.

The plaza was used extensively in the climactic scenes of the 1980 film The Blues Brothers. The interior of the building, as well as the plaza, the Picasso, and the neighboring James R. Thompson Center are also featured in the 1993 film The Fugitive and in 2006's The Lake House. While filming the movie The Dark Knight, instead of using the Chicago Board of Trade Building as the location for the headquarters of Wayne Enterprises as in Batman Begins, film director Christopher Nolan used the Richard J. Daley Center.

Farhad Khoiee-Abbasi, a public protester, is a frequent fixture at the northwest corner of the plaza, near City Hall. Khoiee-Abbasi has been photographed here many times, with his well-dressed appearance, his odd signs, and his general refusal to speak or acknowledge those around him making him a minor celebrity.[7][8]

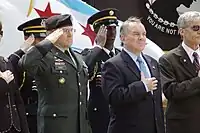

Chief of Staff of the United States Army Gen. George W. Casey, Jr. and Chicago Mayor Richard M. Daley recite the Pledge of Allegiance during May 24, 2008 Memorial Day wreath-laying ceremony at Daley Plaza.

Chief of Staff of the United States Army Gen. George W. Casey, Jr. and Chicago Mayor Richard M. Daley recite the Pledge of Allegiance during May 24, 2008 Memorial Day wreath-laying ceremony at Daley Plaza. The water in the Daley Plaza fountain was dyed team red in honor of the Chicago Blackhawks Stanley Cup run in 2010.

The water in the Daley Plaza fountain was dyed team red in honor of the Chicago Blackhawks Stanley Cup run in 2010.- Christkindlmarket, in 2014. The traditional German market is held in Daley Plaza in December

Richard J. Daley Center and Daley Plaza is Chicago's premier civic center and features a massive sculpture by Pablo Picasso. The modernist skyscraper courthouse is behind the sculpture and to the left is City Hall-County Building

Richard J. Daley Center and Daley Plaza is Chicago's premier civic center and features a massive sculpture by Pablo Picasso. The modernist skyscraper courthouse is behind the sculpture and to the left is City Hall-County Building A view of the plaza at night.

A view of the plaza at night.

Adjacent buildings

Adjacent to the Richard J. Daley Plaza is the landmark City Hall-County Building. Declared a National Historic Landmark and listed on the National Register of Historic Places, it houses offices for the Mayor of Chicago, alderpersons of Chicago's various wards, and chambers for the Chicago City Council. Directly south of the Daley Center is the Cook County Administration Building which is full of office space for County employees. Block 37 containing 108 North State Street is to the east.

Position in skyline

See also

References

- ↑ "Richard J. Daley Center - The Skyscraper Center". Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat.

{{cite web}}: Check|archive-url=value (help)CS1 maint: url-status (link) - 1 2 "Richard J. Daley Center". SkyscraperPage.

- 1 2 "Richard J. Daley Center". The Skyscraper Center. Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat. Retrieved September 12, 2020.

- ↑ Kamin, Blair. "An architecture critic sits on a jury at the Daley Center and sees its majesty with fresh eyes". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved September 9, 2019.

- ↑ "Chicago Civic Center: Perspective View of Plaza". Art Institute of Chicago. 1963. Retrieved December 30, 2023.

- ↑ "Daley Center". Public Building Commission of Chicago. Retrieved September 11, 2009.

- ↑ Selecman, D.L. "Dan's people: One-on-one with the FBI sign guy". Reservoir Magazine.

- ↑ Boose, Greg (April 17, 2009). "The Sign Guy Goes on Hunger Strike". The Huffington Post. Retrieved July 12, 2010.