Rittenhouse Square | |

Rittenhouse Square in October 2010 | |

| |

| Location | Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 39°56′58″N 75°10′19″W / 39.9495°N 75.1719°W |

| Built | 1683 |

| Architect | Thomas Holme and Paul Philippe Cret |

| MPS | Four Public Squares of Philadelphia TR |

| NRHP reference No. | 81000557[1] |

| Added to NRHP | September 14, 1981 |

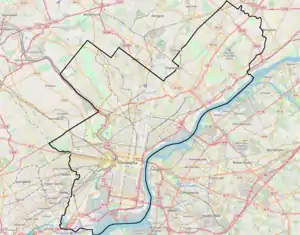

Rittenhouse Square is a neighborhood, including a public park, in Center City Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Rittenhouse Square often specifically refers to the park, while the neighborhood as a whole is referred to simply as Rittenhouse. The park is one of the five original open-space parks planned by William Penn and his surveyor Thomas Holme during the late 17th century.

The neighborhood is among the highest-income urban neighborhoods in the country. Together with Fitler Square, the Rittenhouse neighborhood and the square comprise the Rittenhouse–Fitler Historic District.

Rittenhouse Square Park is maintained by the non-profit group The Friends of Rittenhouse Square.[2] The square cuts off 19th Street at Walnut Street and also at a half-block above Manning Street. Its boundaries are 18th Street to the east, Walnut Street to the north, and Rittenhouse Square West, a north–south boundary street, and Rittenhouse Square South, an east–west boundary street, making the park approximately two short blocks on each side. Locust Street borders Rittenhouse Square to both its east and west in the middle of the square.

History

19th century

Originally called Southwest Square, Rittenhouse Square was renamed in 1825 after David Rittenhouse, a descendant of the first paper-maker in Philadelphia, the German immigrant William Rittenhouse.[3] William Rittenhouse's original paper-mill site is known as Rittenhousetown, located in the rural setting of Fairmount Park along Paper Mill Run. David Rittenhouse was a clockmaker and friend of the American Revolution, as well as a noted astronomer; a lunar crater is named after him.

In the early 19th century, as the city grew steadily from the Delaware River to the Schuylkill River, it became obvious that Rittenhouse Square would become a highly desirable address. James Harper, a merchant and brick manufacturer who had recently retired from the United States Congress, was the first person to build on the square, buying most of the north frontage, erecting a stately townhouse for himself at 1811 Walnut Street (c. 1840). Having thus set the patrician residential tone that would subsequently define the Square, he divided the rest of the land into generously proportioned building lots and sold them. Sold after the congressman's death, the Harper house became the home of the exclusive Rittenhouse Club, which added the present facade in c. 1901.

From 1876 to 1929, Rittenhouse Square was home to several wealthy families including Pennsylvania Railroad president Alexander Cassatt, real estate entrepreneur William Weightman III, department store founder John Wanamaker, Philadelphia planning commission director Edmund Bacon and his son, actor Kevin Bacon, as well as others.

20th century

Elegant architecture like churches and clubs were constructed by John Notman and Frank Furness. The year 1913 brought more changes to the Square's layout when the French architect, Paul Philippe Cret redesigned parts of the Square to resemble Paris and the French gardens. These redesigns include classical entryways and stone additions to railings, pools, and fountains. After World War II, Rittenhouse added to its architecture with modern apartments, office buildings, and condominiums as part of the nation and city's real estate boom. Residential Rittenhouse Square historically housed Victorian mansions but are now replaced largely with high-rise apartments to accommodate the residents that live there, though prominent buildings in Italianate and Art Deco styles remain on Rittenhouse.[4][5][6]

Journalist and author Jane Jacobs wrote about Cret's additions to the park that remain there today. Rittenhouse Square has changed the least out of the city's initial squares. Vacant lots were converted to apartments and hotels, and original mansions were replaced with apartments such as Claridge and Savoy. Jane Jacobs focused on sharing two main ideas in Paul Philippe Cret's redesign, intricacy and centering. Compared with the other four original squares in Philadelphia, Rittenhouse Square has survived proposed alterations that may have changed both its physical layout and character.[6]

In the mid-20th century, conflicts between homosexual and heterosexual communities were common in Center City neighborhoods. Gays and lesbians were found commonly living around Rittenhouse Square and saw the park as a safety zone for camaraderie. For gay men, the park was used as a place to find other men. Hippies and pre-Stonewall gays were also part of their own groups there.[7]

Arts and culture

Today, the tree-filled park is surrounded by high rise residences, luxury apartments, an office tower, a few popular restaurants, a recently shuttered Barnes & Noble bookstore, a Starbucks that has been the center of controversy for racial discrimination,[8] and a five-star hotel. Its green grasses and dozens of benches are popular lunch-time destinations for residents and workers in Philadelphia's Center City neighborhood, while its lion and goat statues are popular gathering spots for small children and their parents. The park is a popular dog walking destination for area residents, as was shown in the fictional film In Her Shoes. The Square was discussed in a favorable light by Jane Jacobs in her seminal work, The Death and Life of Great American Cities.

The Rittenhouse Square neighborhood is also home to many cultural institutions, including the Curtis Institute of Music, Philadelphia Youth Orchestra, the Ethical Society, the Philadelphia Art Alliance, the Rosenbach Museum & Library, Plays & Players, the Wine School of Philadelphia, and the Civil War and Underground Railroad Museum. Delancey Place is a quiet, historical street lined with Civil War-era mansions and the setting for Hollywood movies, located only two blocks south of the square.

The square is home to many works of public art. Among them is a bas-relief bust of J. William White done by R. Tait McKenzie. Billy, the goat was created by Philadelphian Albert Laessle, who also designed the Penguins statue at the Philadelphia Zoo.

Education

Residents are in the Albert M. Greenfield School catchment area for grades kindergarten through eight;[9] all persons assigned to Greenfield are zoned to Benjamin Franklin High School.[10] Previously South Philadelphia High School was the neighborhood's zoned high school.[11]

The Curtis Institute of Music, University of the Arts, and Peirce College are all in the Rittenhouse Square neighborhood.

The Free Library of Philadelphia operates the Philadelphia City Institute on the first floor and lower level of an apartment complex at 1905 Locust Street; the apartment building is known as 220 West Rittenhouse Square .[12]

Transportation

Rittenhouse Square is accessible via several forms of public transportation.

All SEPTA Regional Rail lines stop at Suburban Station, about six blocks north and east of the Square.

The PATCO Speedline, a rapid transit system connecting Philadelphia and Southern New Jersey, has its western terminus at 16th & Locust Sts., 2 blocks east of the Square.

The SEPTA 9, 12, 21, and 42 buses westbound run along Walnut Street. The 17 runs northbound along 20th Street and southbound along 19th Street and Rittenhouse Square West and the 2 runs northbound along 16th Street and southbound along 17th Street.

The SEPTA Subway–Surface Trolley Lines have a station at 19th and Market Streets, two blocks north of the Square. The Walnut-Locust station on the Broad Street Subway is four blocks east.

Gallery

.jpg.webp) An old postcard of Rittenhouse Square looking towards 19th and Walnut Streets

An old postcard of Rittenhouse Square looking towards 19th and Walnut Streets Near northeast corner, May 2005.

Near northeast corner, May 2005. Dr. J. William White Memorial

Dr. J. William White Memorial Lion with a Snake by Antoine-Louis Barye (1832)

Lion with a Snake by Antoine-Louis Barye (1832) James Harper's house at 1811 Walnut St., the home of the Rittenhouse Club (2016)

James Harper's house at 1811 Walnut St., the home of the Rittenhouse Club (2016)

See also

References

- ↑ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. January 23, 2007.

- ↑ "Guide" (PDF). Phila.gov. Retrieved August 22, 2018.

- ↑ "Friends of Rittenhouse". friendsofrittenhouse.org.

- ↑ Merin, Jennifer (June 1, 1986). "Rittenhouse Square gives Philadelphia style". Chicago Tribune. Chicago Tribune. ProQuest 169235714.

- ↑ Skaler, Robert Morris; Keels, Thomas H. (2008). Philadelphia's Rittenhouse Square. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Pub. pp. 7–8. ISBN 978-0-7385-5743-4.

- 1 2 Saska, Jim (May 4, 2016). "On Rittenhouse Square: Perfect from then on". PlanPhilly. Retrieved March 31, 2017.

- ↑ Nickels, Thom (September–October 2003). "Philadelphia Stories". The Gay & Lesbian Review Worldwide; Boston. 10 (5): 25. ProQuest 198663026.

- ↑ "Men arrested at Starbucks say they feared for their lives". Lowellsun.com. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- ↑ "Albert M. Greenfield School." Center City Schools.

- ↑ "High School Directory Fall 2017 Admissions" (Archive). School District of Philadelphia. p. 30/70. Retrieved on November 16, 2016.

- ↑ "Albert M. Greenfield School - Where the Graduates Go." Center City Schools.

- ↑ "Philadelphia City Institute." Free Library of Philadelphia. Retrieved on January 20, 2009.